In many lectures, Rudolf

Steiner spoke about the existence and activity of the great archangels.

He also mentions lesser archangels, though he says little about their nature

or activities. To understand their nature we need to consider how our states

of consciousness are influenced by our participation in communities of like-minded

individuals, and how both of these factors can influence our perception

of what is real.[1] Once we understand these relationships we

can come closer to an understanding of the nature of the archangels. This

understanding can help form the basis for non-sensory experience of these

beings.

From a non-systems point of view an organic being is composed of various parts that function harmoniously together to make the organism. This point of view sees the organism as extrinsically membered into a number of parts that compose the organism. I say extrinsically membered because the parts do not have a inherent (intrinsic) connection with each other. The parts are externally connected through the fact that they happen to belong to an organism.

From a systems viewpoint an organism is a whole that is intrinsically membered into parts. The parts do not happen to belong to the organism. Rather they are parts because they belong to the organism. When we take this holistic view we see the parts as intrinsically connected to the organism as a whole. Part and whole have a different, and more intimate, relationship than we are normally accustomed to. From a systems viewpoint it would be more correct to speak of the part/whole than of the part and whole. The relationship is one where the part and the whole are so intimately connected that they take their meanings from each other.[2] There is no whole without the parts that comprise it, but the parts are only parts because they are "of the whole." Abstract definitions of "part" and "whole" miss this relationship.

The archangels that I am describing have this part/whole character. The parts of which they are composed do not happen to belong together. They are not extrinsic parts. The parts are intrinsic participants in the part/whole that is the archangel. They are parts because they belong to the archangel. If, in this article, I seem to emphasize the parts it is because I am writing from the standpoint of normal daytime consciousness. If, like Steiner, I were to write from the standpoint of angelic consciousness, I would have to speak of the archangels as wholes and write about their individual actions and characteristics.

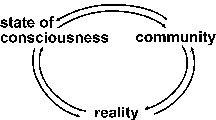

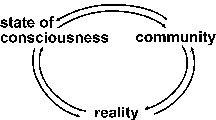

From the standpoint of our normal daytime consciousness there are three components of the body of an archangel. Only one of these is sense perceptible. The others might be called "spiritual states." Understanding these states will occupy most of this article. The first sense-perceptable component is a group of human beings, a community.[3] The second is the state of consciousness possessed by a member of the community, and the third encompasses everything that that the community members consider real. These three elements, community, consciousness, realty, exist in a self-supporting interactive system (Fig. 1). In anthroposophy we know this system as an archangel.

Consciousness and Reality

To understand what it is to be an archangel we must take both our states of consciousness, and the content of these states, seriously. When, in our waking state of consciousness we turn our attention inward we become aware not just of our individuality, but also of what we call the external world as that world is reflected in our consciousness. When we look into our self, we become aware of a specific content, which at that moment of introspection constitutes a large part of our experience of this self. Our direct experience of our self is always of a self that is filled with some content.[4] This content may be a thought, feeling, a mental picture, or even, in higher states of awareness, of a purely spiritual nature. For instance, when I close my eyes and turn my attention inward, I may be aware of pressure from the chair on which I sit, of a patterned darkness that I have learned to associate with having my eyes closed, of the tension of my muscles and a dull discomfort in my back or stomach, of images of people and objects that flit through my consciousness, of myriad remembered sensations, feelings, and experiences that form the content of my momentary consciousness, and that are unified through my memory and sense of self. I do not experience my self as an isolated monad. I experience my self as a being whose consciousness is continually filled with the content of the world I inhabit.

The normal materialistic explanation of this phenomenon is that this content is a reflection of a preexisting physical world. According to this assumption, the world exists outside of us, and is presented to our senses in a form that is essentially complete. Our task as conscious beings is merely to receive and mirror this preexisting world. Although Rudolf Steiner effectively demonstrated that this assumption is unwarranted, to most people it still seems perfectly reasonable. This is likely due to the fact that, as long as we speak and act as if our experience of the world takes place in only one state of consciousness, the content of our consciousness does appear to originate outside of our self in an independent and objective external world. If we lived our whole lives in a single, waking state of consciousness we would always encounter the same type of content when we turned out attention inward. We would always encounter a content that has the same form as the sense world. Under these conditions, the content of our introspection would be linked to the content presented to our senses. The assumption that there is a preexisting world that provides this content arises when we give undue weight to the concept that there is a single, waking state of consciousness. The belief in an external world comes from treating this waking state as unitary, as if there were only one state of consciousness that never varied. However, neither is our waking state of consciousness unitary, nor is it the only state of consciousness that we possess. Our states of consciousness are not unitary, they are legion. As we become aware of this fact, what we know of as the external world begins to appear less like a preexisting given, and more like a multiplicity of potentialities that are translated into perceptions through our activity in various states of consciousness. I elaborate on these ideas, below.

States of Consciousness

During the span of 24 hours we are subject to a great range of conscious states. Steiner frequently spoke of three of these states: waking, dreaming and dreamless sleep. However, we experience many more than these three states. As we drift off to sleep or wake in the morning we pass though or even linger in states of consciousness between sleeping and waking.[5] During these states we are aware of some, but not all, of the perceptions that we have when fully awake. In these states we may have dream-like sensations in which environmental stimuli are incorporated into our half-dream, half-waking consciousness. Once awake, we experience not one, but many different states of consciousness. Our awareness of ourselves is different while we are writing, speaking, eating, or meditating. It also differs as we turn our attention to different stimuli. Immersing oneself is a Bach fugue induces a very different state of consciousness from listing to techno or rap music. In all of these examples we retain a core sense of our self, but we come into relationship with this core in very different ways.

Social Influences on Consciousness

Western culture has developed to the point where our daytime consciousness is the state out of which we interact with the external, physical world. However, given the above we are forced to ask "Which state of daytime consciousness are we referring to?" Up to now I have spoken of a "normal" daytime consciousness as if we knew what that was. The truth is that we have no objective way of defining which of our many states of consciousness is normal. All we can do is accept as normal that state which is tacitly accepted as normal by most of the people who we meet and interact with in our daily lives. In western culture this is the state of consciousness through which we create, accept, and interact with the physical world. To say that our daytime consciousness is our normal state is just another way of saying that most of the people in our culture accept this state as normal. It does not mean that the World[6] is, in its essence, the way we take it to be in this state of consciousness. Our state of consciousness and our perception of reality as having certain properties exist in a mutually supportive relationship. They are two parts of the threefold system we are considering here. Reality is the way we take it to be because we invest it with qualities by crediting a specific state of consciousness, which has that reality as its content. The physical world is the content of our normal waking state of consciousness.

From these considerations we see that the process of selecting one of our multiple states of consciousness as the one out of which we interact with reality is inherently social. It involves the formation of, and communication among, a group of people who cooperate in selecting and defining a mode of consciousness. This community then uses this state of consciousness to define what realty is like.

To help understand how this occurs, it is instructive to turn our attention to non-western cultures. In some non-western cultures individuals experience reality very differently than we do in the west. For instance, the Aranda people of Australia use the term altjiranga mitjina to refer to the time-outside-time that exists in dreams and which, to the Aranda, is also the time in which their ancestors live.[7] To the Aranda there is no difference between the time of their ancestors and the time during which they themselves dream. The term altjiranga mitjina, and the culture that surrounds it, implies a very different relationship to the world than we experience based on our Western objectifying consciousness. To credit the concept of altjiranga mitjina with power and reality the Aranda must approach the world from a different state of consciousness than we do. Our normal daytime consciousness allows us to form theories about dreams and dreaming, but we do not, without having developed higher awareness, experience our ancestors as present among us in a kind of time-outside-time. On the other hand, the more dream-like consciousness of altjiranga mitjina does not lend itself to the perception of enduring objects. Dream objects appear and disappear from the dream world in a way that is not possible for objects in the world of our normal daytime consciousness. The objects and the state of consciousness that engender them exist as components of a self-supporting system. Physical objects only have their characteristic externality because they take their genesis from a state of consciousness that creates externality. In this context it is significant that the aboriginal peoples of Australia created few enduring objects. This lack of artifacts is compatible with the hypothesis that these peoples cultivated a dream-like state of consciousness.

From these considerations we see that though a state of consciousness that allows us to perceive an external world is necessary for the creation of that world, it is not sufficient for this task. Reality is a social construction, not an individual one. The creation and shaping of consciousness in communities reinforces certain parts of our experience at the expense of others. The experiences that are reinforced grow in our experience, while those that find little or no reinforcement decline. The reinforcement of certain parts of experience shapes our states of consciousness because of the intimate relationship between consciousness its contents. As we change the content of our consciousness, we also change conscious states. Turning our attention to dreams put us in one state of consciousness. Giving attention to physical objects puts us in another. As community processes draw our attention to one or the other aspect of our experience, they influence our state of consciousness. A community that accepts the reality of the time-outside-time of altjiranga mitjina engenders a state of consciousness that allows the experience of altjiranga mitjina. Altjiranga mitjina is thus both an experience held by the members of a certain community, and the state of consciousness out of which this experience is possible. In the same way, a physical object is both an element of our experience, and the state of consciousness out of which the object is constructed.

All states of consciousness are substantially influenced by our social interactions: the culture we inhabit, the times we live in, the institutions we attend, the company we keep. Owen Barfield [8] makes a similar point in his elegant book on appearance and reality. He marshals evidence to show that the medieval world was very different from our own. The inhabitants of different historical periods took different kinds of experiences to be about the real world. In this sense, history is a record of changes in consciousness and the concomitant changes in the nature of the world.

Archangels

The picture that has emerged in the preceding sections is one of an interdependence among states of consciousness, social groups, and the constructed reality that is taken as real by these groups. None of these components exists in isolation. They form a system in which the individual elements are linked into a larger whole (Figure 1). The existence of this whole makes it difficult to speak about the individual elements in isolation. I have done so to make the nature of the system clear, but in doing so I have emphasized one or two elements at the expense of the whole. For instance, when I said that a specific state of consciousness engenders specific experiences, I emphasized the creative power of consciousness and played down the role of the community and realty, which cooperate in the process of interpersonal validation of the contents of experience. Interpersonal validations are built out of community interactions with the constructed reality that the community takes to be real. In trying to make one of the three parts of the system clear I inevitably downplay the role of the other two.

Each of the following aphorisms is an attempt to get beyond this problem. Each aphorism starts at one of the points on the circle of dependency (Figure 1), and moves counter-clockwise around the circle. All of the aphorisms are equally true.

One way to move beyond the theoretical framework given here and to come to a more direct experience of the archangels is to recall that it feels different to be with different groups of people. Our consciousness shifts as we come into contact with different groups. What does it feel like to be at home with your family? How is this different from what you feel in your place of employment? What does it feel like to be with a crowd at a sporting event? How is this different from what you experience at an anthroposophical lecture? We all experience these differences, but seldom pay much attention to them. I suggest that they are the result of subtle differences in the nature of the archangels that create the atmosphere in each of these places or situations.

These questions point to minor changes in reality/ community/ consciousness systems that occur within a culture. It is between cultures that more striking differences occur. Different cultures can be based on radically different archangels. It feels different to live in these cultures. This is true even within Europe. It feels different to be in England than on the continent; different to be in France than Germany; different to be in the Italian speaking part of Switzerland than in the French speaking park. The differences are real and immediate. They illustrate that archangels are not merely theoretical. As theory, they are systems. As experience, they shape our lives.

As we begin to speak of reality/ community/ consciousness systems as archangels, our natural tendency is to see the community of individuals as the archangel. This does not do justice to the nature of systems, or of archangels. The group is no more the archangel than is the state of consciousness that is selected and maintained by the community or the reality that is the context of this state. The archangel is the system of reality/ community/ consciousness that both transcends and is immanent in the elements that compose the system. Reality is constructed both by communities and by states of consciousness. None of these factors can be meaningfully isolated from the others. From a systems perspective, reality is constructed out of the context that is the system (Figure 1). The whole context, including reality itself, is the cause of reality.

This article and the archangels

The state of consciousness out of which I wrote this paper was engendered through readings and discussions with other people who share similar ideas. While no one shared exactly my ideas, there were enough similarities to make discussion possible. My views were shaped by these readings and discussions. The more I think about, discuss, and write about these ideas, the more clear they become both to me, and to those with whom I interact. We begin to form a community that shares a specific state of consciousness with a specific content. Knowledge of the structure of an archangel is this content. The reality/ community/ consciousness system I have just described is one of these archangels. My state of consciousness, and yours as you assimilate this content, is an intrinsic part of this being.

From a non-systems point of view an organic being is composed of various parts that function harmoniously together to make the organism. This point of view sees the organism as extrinsically membered into a number of parts that compose the organism. I say extrinsically membered because the parts do not have a inherent (intrinsic) connection with each other. The parts are externally connected through the fact that they happen to belong to an organism.

From a systems viewpoint an organism is a whole that is intrinsically membered into parts. The parts do not happen to belong to the organism. Rather they are parts because they belong to the organism. When we take this holistic view we see the parts as intrinsically connected to the organism as a whole. Part and whole have a different, and more intimate, relationship than we are normally accustomed to. From a systems viewpoint it would be more correct to speak of the part/whole than of the part and whole. The relationship is one where the part and the whole are so intimately connected that they take their meanings from each other.[2] There is no whole without the parts that comprise it, but the parts are only parts because they are "of the whole." Abstract definitions of "part" and "whole" miss this relationship.

The archangels that I am describing have this part/whole character. The parts of which they are composed do not happen to belong together. They are not extrinsic parts. The parts are intrinsic participants in the part/whole that is the archangel. They are parts because they belong to the archangel. If, in this article, I seem to emphasize the parts it is because I am writing from the standpoint of normal daytime consciousness. If, like Steiner, I were to write from the standpoint of angelic consciousness, I would have to speak of the archangels as wholes and write about their individual actions and characteristics.

From the standpoint of our normal daytime consciousness there are three components of the body of an archangel. Only one of these is sense perceptible. The others might be called "spiritual states." Understanding these states will occupy most of this article. The first sense-perceptable component is a group of human beings, a community.[3] The second is the state of consciousness possessed by a member of the community, and the third encompasses everything that that the community members consider real. These three elements, community, consciousness, realty, exist in a self-supporting interactive system (Fig. 1). In anthroposophy we know this system as an archangel.

Consciousness and Reality

To understand what it is to be an archangel we must take both our states of consciousness, and the content of these states, seriously. When, in our waking state of consciousness we turn our attention inward we become aware not just of our individuality, but also of what we call the external world as that world is reflected in our consciousness. When we look into our self, we become aware of a specific content, which at that moment of introspection constitutes a large part of our experience of this self. Our direct experience of our self is always of a self that is filled with some content.[4] This content may be a thought, feeling, a mental picture, or even, in higher states of awareness, of a purely spiritual nature. For instance, when I close my eyes and turn my attention inward, I may be aware of pressure from the chair on which I sit, of a patterned darkness that I have learned to associate with having my eyes closed, of the tension of my muscles and a dull discomfort in my back or stomach, of images of people and objects that flit through my consciousness, of myriad remembered sensations, feelings, and experiences that form the content of my momentary consciousness, and that are unified through my memory and sense of self. I do not experience my self as an isolated monad. I experience my self as a being whose consciousness is continually filled with the content of the world I inhabit.

The normal materialistic explanation of this phenomenon is that this content is a reflection of a preexisting physical world. According to this assumption, the world exists outside of us, and is presented to our senses in a form that is essentially complete. Our task as conscious beings is merely to receive and mirror this preexisting world. Although Rudolf Steiner effectively demonstrated that this assumption is unwarranted, to most people it still seems perfectly reasonable. This is likely due to the fact that, as long as we speak and act as if our experience of the world takes place in only one state of consciousness, the content of our consciousness does appear to originate outside of our self in an independent and objective external world. If we lived our whole lives in a single, waking state of consciousness we would always encounter the same type of content when we turned out attention inward. We would always encounter a content that has the same form as the sense world. Under these conditions, the content of our introspection would be linked to the content presented to our senses. The assumption that there is a preexisting world that provides this content arises when we give undue weight to the concept that there is a single, waking state of consciousness. The belief in an external world comes from treating this waking state as unitary, as if there were only one state of consciousness that never varied. However, neither is our waking state of consciousness unitary, nor is it the only state of consciousness that we possess. Our states of consciousness are not unitary, they are legion. As we become aware of this fact, what we know of as the external world begins to appear less like a preexisting given, and more like a multiplicity of potentialities that are translated into perceptions through our activity in various states of consciousness. I elaborate on these ideas, below.

States of Consciousness

During the span of 24 hours we are subject to a great range of conscious states. Steiner frequently spoke of three of these states: waking, dreaming and dreamless sleep. However, we experience many more than these three states. As we drift off to sleep or wake in the morning we pass though or even linger in states of consciousness between sleeping and waking.[5] During these states we are aware of some, but not all, of the perceptions that we have when fully awake. In these states we may have dream-like sensations in which environmental stimuli are incorporated into our half-dream, half-waking consciousness. Once awake, we experience not one, but many different states of consciousness. Our awareness of ourselves is different while we are writing, speaking, eating, or meditating. It also differs as we turn our attention to different stimuli. Immersing oneself is a Bach fugue induces a very different state of consciousness from listing to techno or rap music. In all of these examples we retain a core sense of our self, but we come into relationship with this core in very different ways.

Social Influences on Consciousness

Western culture has developed to the point where our daytime consciousness is the state out of which we interact with the external, physical world. However, given the above we are forced to ask "Which state of daytime consciousness are we referring to?" Up to now I have spoken of a "normal" daytime consciousness as if we knew what that was. The truth is that we have no objective way of defining which of our many states of consciousness is normal. All we can do is accept as normal that state which is tacitly accepted as normal by most of the people who we meet and interact with in our daily lives. In western culture this is the state of consciousness through which we create, accept, and interact with the physical world. To say that our daytime consciousness is our normal state is just another way of saying that most of the people in our culture accept this state as normal. It does not mean that the World[6] is, in its essence, the way we take it to be in this state of consciousness. Our state of consciousness and our perception of reality as having certain properties exist in a mutually supportive relationship. They are two parts of the threefold system we are considering here. Reality is the way we take it to be because we invest it with qualities by crediting a specific state of consciousness, which has that reality as its content. The physical world is the content of our normal waking state of consciousness.

From these considerations we see that the process of selecting one of our multiple states of consciousness as the one out of which we interact with reality is inherently social. It involves the formation of, and communication among, a group of people who cooperate in selecting and defining a mode of consciousness. This community then uses this state of consciousness to define what realty is like.

To help understand how this occurs, it is instructive to turn our attention to non-western cultures. In some non-western cultures individuals experience reality very differently than we do in the west. For instance, the Aranda people of Australia use the term altjiranga mitjina to refer to the time-outside-time that exists in dreams and which, to the Aranda, is also the time in which their ancestors live.[7] To the Aranda there is no difference between the time of their ancestors and the time during which they themselves dream. The term altjiranga mitjina, and the culture that surrounds it, implies a very different relationship to the world than we experience based on our Western objectifying consciousness. To credit the concept of altjiranga mitjina with power and reality the Aranda must approach the world from a different state of consciousness than we do. Our normal daytime consciousness allows us to form theories about dreams and dreaming, but we do not, without having developed higher awareness, experience our ancestors as present among us in a kind of time-outside-time. On the other hand, the more dream-like consciousness of altjiranga mitjina does not lend itself to the perception of enduring objects. Dream objects appear and disappear from the dream world in a way that is not possible for objects in the world of our normal daytime consciousness. The objects and the state of consciousness that engender them exist as components of a self-supporting system. Physical objects only have their characteristic externality because they take their genesis from a state of consciousness that creates externality. In this context it is significant that the aboriginal peoples of Australia created few enduring objects. This lack of artifacts is compatible with the hypothesis that these peoples cultivated a dream-like state of consciousness.

From these considerations we see that though a state of consciousness that allows us to perceive an external world is necessary for the creation of that world, it is not sufficient for this task. Reality is a social construction, not an individual one. The creation and shaping of consciousness in communities reinforces certain parts of our experience at the expense of others. The experiences that are reinforced grow in our experience, while those that find little or no reinforcement decline. The reinforcement of certain parts of experience shapes our states of consciousness because of the intimate relationship between consciousness its contents. As we change the content of our consciousness, we also change conscious states. Turning our attention to dreams put us in one state of consciousness. Giving attention to physical objects puts us in another. As community processes draw our attention to one or the other aspect of our experience, they influence our state of consciousness. A community that accepts the reality of the time-outside-time of altjiranga mitjina engenders a state of consciousness that allows the experience of altjiranga mitjina. Altjiranga mitjina is thus both an experience held by the members of a certain community, and the state of consciousness out of which this experience is possible. In the same way, a physical object is both an element of our experience, and the state of consciousness out of which the object is constructed.

All states of consciousness are substantially influenced by our social interactions: the culture we inhabit, the times we live in, the institutions we attend, the company we keep. Owen Barfield [8] makes a similar point in his elegant book on appearance and reality. He marshals evidence to show that the medieval world was very different from our own. The inhabitants of different historical periods took different kinds of experiences to be about the real world. In this sense, history is a record of changes in consciousness and the concomitant changes in the nature of the world.

Archangels

The picture that has emerged in the preceding sections is one of an interdependence among states of consciousness, social groups, and the constructed reality that is taken as real by these groups. None of these components exists in isolation. They form a system in which the individual elements are linked into a larger whole (Figure 1). The existence of this whole makes it difficult to speak about the individual elements in isolation. I have done so to make the nature of the system clear, but in doing so I have emphasized one or two elements at the expense of the whole. For instance, when I said that a specific state of consciousness engenders specific experiences, I emphasized the creative power of consciousness and played down the role of the community and realty, which cooperate in the process of interpersonal validation of the contents of experience. Interpersonal validations are built out of community interactions with the constructed reality that the community takes to be real. In trying to make one of the three parts of the system clear I inevitably downplay the role of the other two.

Each of the following aphorisms is an attempt to get beyond this problem. Each aphorism starts at one of the points on the circle of dependency (Figure 1), and moves counter-clockwise around the circle. All of the aphorisms are equally true.

Reality: A shared perception of reality defines and gives meaning to a community that maintains a state of consciousness in a way that allows this realty to manifest itself.The individual instances of this tripartite system of reality, community and consciousness are archangels. Though constituted differently, they share many characteristics with other types of beings. They have their own qualities, tendencies, temporal extent, and can be resistant to change. Just as different species of biological organisms have different characteristics, different archangels have different characters. We feel these characters through our experiences as members of different communities. We experience the world differently when we are with different people.

Community: Participation in a community induces a state of consciousness that allows the World to manifest itself in a way that is real to the community.

State of consciousness: A state of consciousness takes as its content that aspect of the World that the community finds to be real.

One way to move beyond the theoretical framework given here and to come to a more direct experience of the archangels is to recall that it feels different to be with different groups of people. Our consciousness shifts as we come into contact with different groups. What does it feel like to be at home with your family? How is this different from what you feel in your place of employment? What does it feel like to be with a crowd at a sporting event? How is this different from what you experience at an anthroposophical lecture? We all experience these differences, but seldom pay much attention to them. I suggest that they are the result of subtle differences in the nature of the archangels that create the atmosphere in each of these places or situations.

These questions point to minor changes in reality/ community/ consciousness systems that occur within a culture. It is between cultures that more striking differences occur. Different cultures can be based on radically different archangels. It feels different to live in these cultures. This is true even within Europe. It feels different to be in England than on the continent; different to be in France than Germany; different to be in the Italian speaking part of Switzerland than in the French speaking park. The differences are real and immediate. They illustrate that archangels are not merely theoretical. As theory, they are systems. As experience, they shape our lives.

As we begin to speak of reality/ community/ consciousness systems as archangels, our natural tendency is to see the community of individuals as the archangel. This does not do justice to the nature of systems, or of archangels. The group is no more the archangel than is the state of consciousness that is selected and maintained by the community or the reality that is the context of this state. The archangel is the system of reality/ community/ consciousness that both transcends and is immanent in the elements that compose the system. Reality is constructed both by communities and by states of consciousness. None of these factors can be meaningfully isolated from the others. From a systems perspective, reality is constructed out of the context that is the system (Figure 1). The whole context, including reality itself, is the cause of reality.

This article and the archangels

The state of consciousness out of which I wrote this paper was engendered through readings and discussions with other people who share similar ideas. While no one shared exactly my ideas, there were enough similarities to make discussion possible. My views were shaped by these readings and discussions. The more I think about, discuss, and write about these ideas, the more clear they become both to me, and to those with whom I interact. We begin to form a community that shares a specific state of consciousness with a specific content. Knowledge of the structure of an archangel is this content. The reality/ community/ consciousness system I have just described is one of these archangels. My state of consciousness, and yours as you assimilate this content, is an intrinsic part of this being.

Footnotes

1. Burns and Engdahl (1998) work toward a

similar understanding, but without linking it to Steiner's conception of

the archangels. Burns, T. R and Engdahl, E. (1998), 'The Social Construction

of Consciousness. Part 1: Collective Consciousness and Its Socio-Cultural

Foundations. Journal of Consciousness Studies 5, pp. 67-85.2. Bortoft, H. (1996), The Wholeness of Nature (Hudson, NY: Lindisfarne Press).

3. I use the word community in a very broad sense to mean a group of individuals who feel themselves united by common views or in search for a common goal. In this sense, a community can be as small as two people or as large as a culture.

4. Husserl, E. (1913/1962), Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology (New York: Collier Books).

5. Hypnagogic and hypnopompic states, pp. 74-114 in Tart, C. T. (1969), Altered States of Consciousness (New York: John Wiley & Sons).

6. "World" is capitalized to indicate that is has a different meaning from its non-capitalized form (world). It is difficult to explain, in a short space, what I mean by the word "World." Barfield (1965) approaches my meaning with his concept of the unrepresented. For Barfield, the unrepresented is the ground of existence as described by contemporary physics. He is struck by the discrepancy between our experiences and this underlying ground. Faced with this discrepancy he concludes that the multitude of perceptions that we call reality are really representations (or figurations, to use his term) of the ground. I want to go one step farther. To me, the theories of physics are also constructions of reality. We cannot rely on these theories for a direct description of the ground of the world (the World). The World is what reality is like before it is figured into perceptions by our sense apparatus and thinking. We become aware of its existence only through our experience of agreement/disagreement with other people. It is the basis for all agreements and disagreements. I am tempted to say that the World is that which underlies the content of consciousness: the content (reality) on which communities agree. However, this formulation tends to objectify the World, to give it thing-like qualities. The word "underlies" implies that there is some physical thing that lies under the characteristic content of our states of consciousness. The World cannot have thing-like characteristics because the quality of "thingness" is a community creation as much as any physical object. The World is no-thing with no-characteristics. At the same time it is expressed in and through all things and all characteristics. It is the no-thing expressed in all things. It is no-consciousness expressed in all consciousness. In these senses, it is similar to the Buddhist concept of emptiness.

7. Rheingold, H. (1988), They Have a Word For It (Los Angeles, CA: Jeremy P. Tarcher, Inc.).

8. Barfield, O. (1965), Saving the Appearances (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World).