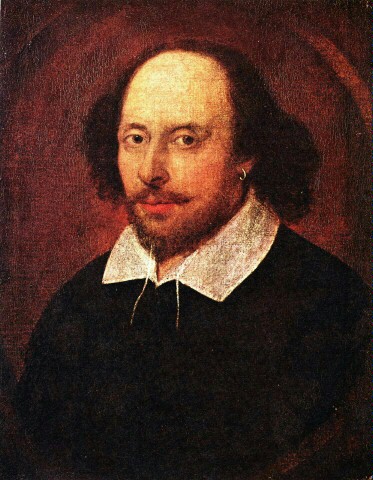

Will: William Shakespeare

Ben: Ben Jonson

ARISE, shine: for thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee.

2. For, behold, the darkness shall cover the earth, and gross darkness the people: but the Lord shall arise upon thee, and his glory shall be seen upon thee.

3. And the Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the brightness of thy rising.

19. The sun shall be no more thy light by day; neither for brightness shall the moon give light unto thee: but the Lord shall be unto thee an everlasting light, and thy God thy glory.

20. Thy sun shall no more go down; neither shall thy moon withdraw itself: for the Lord shall be thine everlasting light, and the days of thy mourning shall be ended.

THEY SEATED THEMSELVES in the heavy chairs on the pebbled floor beneath the eaves of the summer-house by the orchard. A table between them carried wine and glasses, and a packet of papers, with pen and ink. The larger man of the two, his doublet unbuttoned, his broad face blotched and scarred, puffed a little as he came to rest. The other picked an apple from the grass, bit it, and went on with the thread of the talk that they must have carried out of doors with them.

'But why waste time fighting atomies who do not come up to your belly-button, Ben?' he asked.

'It breathes me - it breathes me, between bouts! You'd be better for a tussle or two.'

'But not to spend mind and verse on 'em. What was Dekker to you? Ye knew he'd strike back - and hard.'

'He and Marston had been baiting me like dogs ... about my trade as they called it, though it was only my cursed stepfather's. "Bricks and mortar," Dekker said, and "hod-man". And he mocked my face. 'Twas clean as curds in my youth. This humour has come on me since.'

'Ah! "Every man and his humour"? But why did ye not have at Dekker in peace - over the sack, as you do at me?'

'Because I'd have drawn on him - and he's no more worth a hanging than Gabriel. Setting aside what he wrote of me, too, the hireling dog has merit, of a sort. His Shoe-maker's Holiday. Hey ? Though my Bartlemy Fair, when 'tis presented, will furnish out three of it and -'

'Ride all the easier. I have suffered two readings of it already. It creaks like an overloaded hay-wain,' the other cut in. 'You give too much.'

Ben smiled loftily, and went on. 'But I'm glad I lashed him in my Poetaster, for all I've worked with him since. How comes it that I've never fought with thee, Will?'

First, Behemoth, the other drawled, 'it needs two to engender any sort of iniquity. Second, the betterment of this present age - and the next, maybe - lies, in chief, on our four shoulders. If the Pillars of the Temple fall out, Nature, Art, and Learning come to a stand. Last, I am not yet ass enough to hawk up my private spites before the groundlings. What do the Court, citizens, or 'prentices give for thy fallings-out or fallings-in with Dekker - or the Grand Devil?'

'They should be taught, then - taught.'

'Always that? What's your commission to enlighten us?'

'My own learning which I have heaped up, lifelong, at my own pains. My assured knowledge, also, of my craft and art. I'll suffer no man's mock or malice on it.'

'The one sure road to mockery.'

'I deny nothing of my brain-store to my lines. I - I build up my own works throughout.'

'Yet when Dekker cries "hodman" y'are not content.'

Ben half heaved in his chair. 'I'll owe you a beating for that when I'm thinner. Meantime here's on account. I say I build upon my own foundations; devising and perfecting my own plots; adorning 'em justly as fits time, place, and action. In all of which you sin damnably. I set no landward principalities on sea-beaches.'

'They pay their penny for pleasure - not learning,' Will answered above the apple-core.

'Penny or tester, you owe 'em justice. In the facture of plays - nay, listen, Will - at all points they must he dressed historically - teres atque rotundus - in ornament and temper. As my Sejanus, of which the mob was unworthy.'

Here Will made a doleful face, and echoed, 'Unworthy! I was - what did I play, Ben, in that long weariness? Some most grievous ass.'

'The part of Caius Silius,' said Ben stiffly.

Will laughed aloud. 'True. "Indeed that place was not my sphere."'

It must have been a quotation, for Ben winced a little, ere he recovered himself and went on: 'Also my Alchemist which the world in part apprehends. The main of its learning is necessarily yet hid from 'em. To come to your works, Will - '

'I am a sinner on all sides. The drink's at your elbow.'

'Confession shall not save ye - nor bribery.' Ben filled his glass. 'Sooner than labour the right cold heat to devise your own plots you filch, botch, and clap 'em together out o' ballads, broadsheets, old wives' tales, chap-books - '

Will nodded with complete satisfaction. 'Say on', quoth he.

"Tis so with nigh all yours. I've known honester jack-daws. And whom among the learned do ye deceive? Reckoning up those - forty, is it? - your plays You've misbegot, there's not six which have not plots common as Moorditch.'

'Ye're out, Ben. There's not one. My Love's Labour (how I came to write it, I know not) is nearest to lawful issue. My Tempest (how I came to write that, I know) is, in some part my own stuff. Of the rest, I stand guilty. Bastards all !

'And no shame?'

'None! Our business must be fitted with parts hot and hot - and the boys are more trouble than the men. Give me the bones of any stuff, I'll cover 'em as quickly as any. But to hatch new plots is to waste God's unreturning time like a -' - he chuckled - 'like a hen.'

'Yet see what ye miss! Invention next to Knowledge, whence it proceeds, being the chief glory of Art - '

'Miss, say you? Dick Burbage - in my Hamlet that I botched for him when he had staled of our Kings? (Nobly he played it.) Was he a miss?'

Ere Ben could speak Will overbore him.

'And when poor Dick was at odds with the world in general and womankind in special, I clapped him up my Lear for a vomit.'

'An hotchpotch of passion, outrunning reason,' was the verdict.

'Not altogether. Cast in a mould too large for any boards to bear. (My fault!) Yet Dick evened it. And when he'd come out of his whoremongering aftermaths of repentance, I served him my Macbeth to toughen him. Was that a miss ?'

'I grant your Macbeth as nearest in spirit to my Sejanus; showing for example: "How fortune plies her sports when she begins To practise 'em." We'll see which of the two lives longest.'

'Amen! I'll bear no malice among the worms.'

A liveried man, booted and spurred, led a saddle-horse through a gate into the orchard. At a sign from Will he tethered the beast to a tree, lurched aside, and stretched on the grass. Ben, curious as a lizard, for all his bulk, wanted to know what it meant.

'There's a nosing Justice of the Peace lost in thee,' Will returned. 'Yon's a business I've neglected all this day for thy fat sake - and he by so much the drunker�.Patience! It's all set out on the table. Have a care with the ink!'

Ben reached unsteadily for the packet of papers and read the superscription:' "To William Shakespeare, Gentleman, at his house of New Place in the town of Stratford, these - with diligence from M.S." Why does the fellow withhold his name? Or is it one of your women? I'll look.'

Muzzy as he was, he opened and unfolded a mass of printed papers expertly enough.

'From the most learned divine, Miles Smith of Brazen Nose College,' Will explained. 'You know this business as well as I. The King has set all the scholars of England to make one Bible, which the Church shall be bound to, out of all the Bibles that men use.'

'I knew.' Ben could not lift his eyes from the printed page. 'I'm more about Court than you think. The learning of Oxford and Cambridge - "most noble and most equal," as I have said - and Westminster, to sit upon a clutch of Bibles. Those 'ud be Geneva (my mother read to me out of it at her knee), Douai, Rheims, Coverdale, Matthew's, the Bishops', the Great, and so forth.'

'They are all set down on the page there - text against text. And you call me a botcher of old clothes?'

'Justly. But what's your concern with this botchery? To keep peace among the Divines? There's fifty of 'em at it as I've heard.'

'I deal with but one. He came to know me when we played at Oxford - when the plague was too hot in London.'

'I remember this Miles Smith now. Son of a butcher? Hey?' Ben grunted.

'Is it so?' was the quiet answer. 'He was moved, he said, with some lines of mine in Dick's part. He said they were, to his godly apprehension, a parable, as it might be, of his reverend self, going down darkling to his tomb 'twixt cliffs of ice and iron.'

'What lines? I know none of thine of that power. But in my Sejanus -'

These were in my Macbeth. They lost nothing at Dick's mouth:-

' "To-morrow, and tomorrow, and to-morrow

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death -"

or something in that sort. Condell writes 'em out fair for him, and tells him I am Justice of the Peace (wherein he lied) and armiger, which brings me within the pale of God's creatures and the Church. Little and little, then, this very reverend Miles Smith opens his mind to me. He and a half-score others, his cloth, are cast to furbish up the Prophets - Isaiah to Malachi. In his opinion by what he'd heard, I had some skill in words, and he'd condescend - '

'How?' Ben barked. 'Condescend?'

'Why not? He'd condescend to inquire o' me privily, when direct illumination lacked, for a tricking-out of his words or the turn of some figure. For example ' - Will pointed to the papers - 'here be the first three verses of the Sixtieth of Isaiah, and the nineteenth and twentieth of that same. Miles has been at a stand over 'em a week or more.'

'They never called on me.' Ben caressed lovingly the hand-pressed proofs on their lavish linen paper. 'Here's the Latin atop and' - his thick forefinger ran down the slip - 'some three - four - Englishings out of the other Bibles. They spare 'emselves nothing. Let's to it together. Will you have the Latin first?'

'Could I choke ye from that, Holofernes?'

Ben rolled forth, richly: "'Surge, illumare, Jerusalem, quia venit lumen tuum, et gloria Domini super te orta est. Quia ecce tenebrae aperient terram et caligo populos. Super te autem orietur Dominus, et gloria ejus in te videbitur. Et ambulabunt gentes in lumine tuo, et reges in splendore ortus tui." Er-hum? Think you to better that?'

'How have Smith's crew gone about it?'

'Thus.' Ben read from the paper. "'Get thee up, O Jerusalem, and be bright, for thy light is at hand. and the glory of God has risen up upon thee."'

'Up-pup-up!' Will stuttered profanely.

Ben held on. "'See how darkness is upon the earth and the peoples thereof."'

'That's no great stuff to put into Isaiah's mouth. And further, Ben?'

"'But on thee God shall shew light and on-" or "in," is it?' (.Ben held the proof closer to the deep furrow at the bridge of his nose.) '"on thee shall His glory be manifest. So that all peoples shall walk in thy light and the Kings in the glory of thy morning."'

'It may be mended. Read me the Coverdale of it now. 'Tis on the same sheet - to the right, Ben.'

'Umm-umm! Coverdale saith, "And therefore get thee up betimes, for thy light cometh, and the glory of the Lord shall rise up upon thee. For lo! while the darkness and cloud covereth the earth and the people, the Lord shall shew thee light, and His glory shall be seen in thee. The Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the brightness that springeth forth upon thee." But "gentes" is for the most part, "peoples" Ben concluded.

'Eh?' said Will indifferently. 'Art sure?'

This loosed an avalanche of instances from Ovid, Quintilian, Terence, Columella, Seneca, and others. Will took no heed till the rush ceased. but stared into the orchard through the September haze. 'Now give me the Douai and Geneva for this "Get thee up, O Jerusalem,"' said he at last.

'They'll be all there.' Ben referred to the proofs. "Tis "arise" in both,' said he. "'Arise and be bright" in Geneva. In the Douai 'tis "Arise and be illuminated."'

'So? Give me the paper now.' Will took it from his companion, rose, and paced towards a tree in the orchard, turning again, when he had reached it, by a well-worn track through the grass. Ben leaned forward in his chair. The other's free hand went up warningly.

'Quiet, man!' said he. 'I wait on my Demon!' He fell into the stage-stride of his art at that time, speaking to the air.

'How shall this open? "Arise?" No! "Rise!" Yes. And we'll no weak coupling. 'Tis a call to a City! "Rise - shine" . . . Nor yet any schoolmaster's "because" - because Isaiah is not Holofernes. "Rise- shine; for thy light is come, and -!" ' He refreshed himself from the apple and the proofs as he strode. "'And - and the glory of God!" - No "God's"'s over short. We need the long roll here.

"And the glory of the Lord is risen on thee." (Isaiah speaks the part. We'll have it from his own lips.) What's next in Smith's stuff? . . . "See how?" Oh, vile - vile! ... And Geneva hath "Lo"? (Still, Ben! Still!) "Lo" is better by all odds: but to match the long roll of "the Lord" we'll have it "Behold." How goes it now? For, behold, darkness clokes the earth and - and -"What's the colour and use of this cursed caligo, Ben? - "Et caligo populos."'

' "Mistiness" or, as in Pliny, "blindness." And further-'

'No-o ... Maybe, though, caligo will piece out tenebrae. "Quia ecce tenebrae operient terram et caligo populos." Nay! "Shadow" and "mist" are not men enough for this work ... Blindness. did ye say, Ben? ... The blackness of 'blindness atop of mere darkness? ... By God, I've used it in my own stuff many times! "Gross" searches it to the hilts! "Darkness covers" - no -"clokes" (short always). "Darkness clokes the earth, and gross - gross darkness the people!" (But Isaiah's prophesying, with the storm behind him. Can ye not feel it, Ben? It must be "shall") - "Shall cloke the earth" ... The rest comes clearer .... But on thee God Shall arise" ... (Nay, that's sacrificing the Creator to the Creature!) "But the Lord shall arise on thee", and - yes, we sound that "thee" again - "and on thee shall" - No! ... "And His glory shall be seen on thee." Good!' He walked his beat a little in silence, mumbling the two verses before he mouthed them.

'I have it! Heark, Ben! "Rise - shine; for thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord is risen on thee. For, behold, darkness shall cloke the earth, and gross darkness the people. But the Lord shall arise on thee, and His glory shall be seen upon thee."'

'There's something not all amiss there,' Ben conceded.

'My Demon never betrayed me yet, while I trusted him. Now for the verse that runs to the blast of rams'- horns. "Et ambulabunt gentes in lumine tuo, et reges in splendore ortus tui." How goes that in the Smithy? "The Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the brightness that springs forth upon thee?" The same in Coverdale and the Bishops' - eh? We'll keep "Gentiles," Ben, for the sake of the indraught of the last syllable. But it might be "And the Gentiles shall draw." No! The plainer the better! "The Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the splendour of -" (Smith's out here! We'll need something that shall lift the trumpet anew.) "Kings shall - shall - Kings to -" (Listen, Ben, but on your life speak not!) "Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to thy bright-ness" - No! "Kings to the brightness that springeth-" Serves not! ... One trumpet must answer another. And the blast of a trumpet is always ai-ai. "The brightness of" - "Ortus" signifies "rising," Ben - or what?'

'Ay, or "birth," or the East in general.'

'Ass! 'Tis the one word that answers to "light." "Kings to the brightness of thy rising." Look! The thing shines now within and without. God! That so much should lie on a word!' He repeated the verse - "And the Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the brightness of thy rising."'

He walked to the table and wrote rapidly on the proof margin all three verses as he had spoken them. 'If they hold by this', said he, raising his head, 'they'll not go far astray. Now for the nineteenth and twentieth verses. On the other sheet, Ben. What? What? Smith says he has held back his rendering till he hath seen mine? Then we'll botch 'em as they stand. Read me first the Latin; next the Coverdale, and last the Bishops'. There's a contagion of sleep in the air.' He handed back the proofs, yawned, and took up his walk.

Obedient, Ben began: "'Non erit tibi amplius Sol ad lucendum per diem, nec splendor Lunae illuminabit te." Which Coverdale rendereth, "The Sun shall never be thy day light, and the light of the Moon shall never shine unto thee." The Bishops read: "Thy sun shall never be thy daylight and the light of the moon shall never shine on thee."'

'Coverdale is the better,' said Will, and, wrinkling his nose a little,'The Bishops put out their lights clumsily. Have at it, Ben.'

Ben pursed his lips and knit his brow. 'The two verses are in the same mode, changing a hand's-breadth in the second. By so much, therefore, the more difficult.'

'Ye see that, then?' said the other, staring past him, and muttering as he paced, concerning suns and moons. Presently he took back the proof, chose him another apple, and grunted. 'Umm-umm! "Thy Sun shall never be - No! Flat as a split viol. "Non erit tibi amplius Sol-" That amplius must give tongue.

Ah! . . . "Thy Sun shall not - shall not - shall no more be thy light by day" A fair entry. "Nor?" - No! Not on the heels of "day." "Neither" it must be - "Neither the Moon" - but here's splendor and the rams'-horns again. (Therefore - ai-ai!) "Neither for brightness shall the Moon -" (Pest! It is the Lord who is taking the Moon's place over Israel. It must be "thy Moon.") "Neither for brightness shall thy Moon light - give - make - give light unto thee." Ah! . . . Listen here! . . . "The Sun shall no more be thy light by day: neither for brightness shall thy Moon give light unto thee." That serves, and more, for the first entry. What next, Ben?'

Ben nodded magisterially as Will neared him, reached out his hand for the proofs, and read: '"Sed erit tibi Dominus in lucem sempiternam et Deus tuus in gloriam tuam." Here is a jewel of Coverdale's that the Bishops have wisely stolen whole. Hear! "But the Lord Himself shall be thy everlasting light, and thy God shall be thy glory."' Ben paused. 'There's a hand's-breadth of splendour for a simple man to gather!'

'Both hands rather. He's swept the strings as divinely as David before Saul', Will assented. 'We'll convey it whole, too.... What's amiss now, Holofernes?'

For Ben was regarding him with a scholar's cold pity. 'Both hands! Will, hast thou ever troubled to master any shape or sort of prosody - the mere names of the measures and pulses of strung words?'

'I beget some such stuff and send it to you to christen. What's your wisdomhood in labour of?'

'Naught. Naught. But not to know the names of the tools of his trade!' Ben half muttered and pronounced some Greek word or other which conveyed nothing to the listener, who replied: 'Pardon, then, for whatever sin it was. I do but know words for my need of 'em. Ben. Hold still awhile!'

He went back to his pacings and mutterings. "'For the Lord Himself shall be thy - or thine? - everlasting light." Yes. We'll convey that.' He repeated it twice. 'Nay! Can be bettered. Hark ye, Ben. Here is the Sun going up to over-run and possess all Heaven for evermore. Therefore (Still, man!) we'll harness the horses of the dawn. Hear their hooves? "The Lord Himself shall be unto thee thy everlasting light, and -" Hold again! After that climbing thunder must be some smooth check - like great wings gliding. Therefore we'll not have "shall be thy glory," but "And thy God thy glory!" Ay - even as an eagle alighteth! Good - good! Now again, the sun and moon of that twentieth verse, Ben.'

Ben read: '"Non occidet ultra Sol tuus et Luna tua non minuetur: quia erit tibi Dominus in lucem sempiternam et complebuntur dies luctus tui."

Will snatched the paper and read aloud from the Coverdale version. "'Thy Sun shall never go down, and thy Moon shall not be taken away ...... What a plague's Coverdale doing with his blocking ets and urs, Ben? What's minuetur? ... I'll have it all anon.'

'Minish - make less - appease - abate, as in-'

'So?' Will threw the proofs back. 'Then "wane" should serve. "Neither shall thy moon wane .... "Wane" is good, but over-weak for place next to "moon"' � He swore softly. 'Isaiah hath abolished both earthly sun and moon. Exeunt ambo. Aha! I begin to see ! ... Sol, the man, goes down - down stairs or trap - as needs be. Therefore "Go down" shall stand. "Set" would have been better- as a sword sent home in the scabbard - but it jars - it jars. Now Luna must retire herself in some simple fashion ... Which? Ass that I be! 'Tis common talk in all the plays�

"Withdrawn" � "Favour withdrawn" ... "Countenance withdrawn." "The Queen withdraws herself" � "Withdraw," it shall be! "Neither shall thy moon withdraw herself." (Hear her silver train rasp the boards, Ben?) "Thy sun shall no more go down - neither shall thy moon withdraw herself. For the Lord. . ." - ay, the Lord, simple of Himself - "shall be thine" - yes, "thine" here - "everlasting light, and"�How goes the ending, Ben?'

'"Et complebuntur dies luctus tui."' Ben read. '"And thy sorrowful days shall be rewarded thee," says Coverdale.'

'And the Bishops?'

'"And thy sorrowful days shall be ended."'

'By no means. And Douai?'

'"Thy sorrow shall be ended."'

'And Geneva?'

'"And the days of thy mourning shall be ended."'

'The Switzers have it! Lay the tail of Geneva to the head of Coverdale and the last is without flaw.

He began to thump Ben on the shoulder. 'We have it! I have it all, Boanerges! Blessed be my Demon! Hear!

"The sun shall no more be thy light by day, neither for brightness the moon by night. But the Lord Himself shall be unto thee thy everlasting light, and thy God thy glory."

' He drew a deep breath and went on.

'"Thy sun shall no more go down; neither shall thy moon withdraw herself, for the Lord shall be thine everlasting light, and the days of thy mourning shall be ended."'

The rain of triumphant blows began again. 'If those other seven devils in London let it stand on this sort, it serves. But God knows what they can not turn upsee-dejee!'

Ben wriggled. 'Let be!' he protested. 'Ye are more moved by this jugglery than if the Globe were burned.'

'Thatch - old thatch! And full of fleas! ... But, Ben, ye should have heard my Ezekiel making mock of fallen Tyrus in his twenty-seventh chapter. Miles sent me the whole, for, he said, some small touches. I took it to the Bank - four o'clock of a summer morn; stretched out in one of our wherries - and watched London, Port and Town, up and down the river, waking all arrayed to heap more upon evident excess. Ay! "A merchant for the peoples of many isles" ... "The ships of Tarshish did sing of thee in thy markets"? Yes! I saw all Tyre before me neighing her pride against lifted heaven... But what will they let stand of all mine at long last? Which? I'll never know.'

He had set himself neatly and quickly to refolding and cording the packet while he talked. 'That's secret enough,' he said at the finish.

'He'll lose it by the way.' Ben pointed to the sleeper beneath the tree. 'He's owl-drunk.'

'But not his horse,' said Will. He crossed the orchard, roused the man; slid the packet into an holster which he carefully rebuckled; saw him out of the gate, and returned to his chair.

'Who will know we had part in it?' Ben asked.

'God, maybe - if He ever lay ear to earth. I've gained and lost enough - lost enough.' He lay back and sighed. There was long silence till he spoke half aloud. 'And Kit that was my master in the beginning, he died when all the world was young.'

'Knifed on a tavern reckoning - not even for a wench!' Ben nodded.

'Ay. But if he'd lived he'd have breathed me! 'Fore God, he'd have breathed me!'

'Was Marlowe, or any man, ever thy master, Will?'

'He alone. Very he. I envied Kit. Ye do not know that envy, Ben?'

'Not as touching my own works. When the mob is led to prefer a baser Muse, I have felt the hurt, and paid home. Ye know that - as ye know my doctrine of play-writing.'

'Nay - not wholly - tell it at large,' said Will, relaxing in his seat, for virtue had gone out of him. He put a few drowsy questions. In three minutes Ben had launched full-flood on the decayed state of the drama, which he was born to correct; on cabals and intrigues against him which he had fought without cease; and on the inveterate muddle-headedness of the mob unless duly scourged into approbation by his magisterial hand.

It was very still in the orchard now that the horse had gone. The heat of the day held though the sun sloped and the wine had done its work. Presently, Ben's discourse was broken by a snort from the other chair.

'I was listening, Ben! Missed not a word - missed not a word.' Will sat up and rubbed his eyes. 'Ye held me throughout.' His head dropped again before he had done speaking.

Ben looked at him with a chuckle and quoted from one of his own plays:-

'"Mine earnest vehement botcher

And deacon also, Will, I cannot dispute with you."'

' He drew out flint, steel and tinder, pipe and tobacco-bag from somewhere round his waist, lit and puffed against the midges till he, too, dozed.

This was the last story to be written by Rudyard Kipling. It was completed too late for inclusion in Limits and Renewals, his last collection, published in London in April 1932. It was published in The Strand magazine in April 1934, and reprinted in The Strand in 1947 with an introduction by Hilton Brown. It is also to be found in volume 30 of the Sussex Edition.

"Proofs of Holy Writ" was said to have arisen from a dinner table conversation between Kipling and John Buchan about the process by which the splendidly poetic language of the King James' Authorised Version of the Bible miraculously emerged from a committee of 47 learned men. Might they, Buchan wondered, have consulted the great creative writers of the day, like Will Shakespeare or Ben Jonson ? 'That's an idea', said Kipling, and he went away to turn it into a tale.