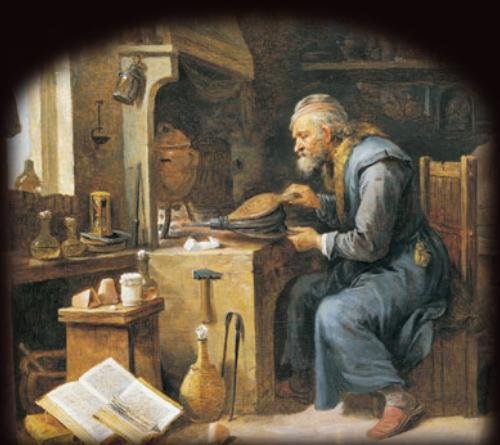

Alchemy and Anthroposophy

by Keith Francis

The second of three lectures at the Anthroposophical Society, New York Branch

�

Lecture 2

October 25, 2007

Greek Philosophers and Mediaeval Alchemists

Most of last week�s talk was devoted to establishing a background for the study of alchemy � understanding how the withdrawal of the divine beings who had cared for human evolution and the development of an increasingly clear daytime consciousness led to the study of the workings of the spirit in nature and of nature in the light of the spirit. This still needed divine guidance in the form of the teachings of Hermes Trismegistos. The tradition of these teachings came into the modern world through the hermetic writings that appeared in the third century AD but undoubtedly still contained traces of their divine origin.

While alchemical work went on all over the world in the immediate pre-Christian centuries, the European impulse came largely from the part of Egypt which had come most strongly under Greek influence with the foundation of Alexandria, the city of Alexander the Great, in about 331 BC. �Alex�, as the British Tommies in the Second World War used to call the city, was Egypt's capital for nearly a thousand years, until the Arabs conquered Egypt in 641 AD. There is a story that Homer had appeared to Alexander in a dream and told him that he would build his city on "An island set in an ocean deep, which lies off far Egypt's rich and fertile land, and the name of the island is called Pharos". This became the site of the most famous lighthouse in history, but the city itself was built on the mainland. Alexander intended that his city should be the link between Greece and the rich Nile Valley and in this he was successful. Within a century it became the largest in the world, and for some centuries more it was second only to Rome. It became a great centre of learning, with a huge library, a famous lighthouse and an extraordinary mix of Greeks from many cities and backgrounds. Alexandria was not only a center of Hellenism but was also home to the largest Jewish community in the world. The Septuagint, a highly influential Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, was produced there. Alexander, however, did not live to see the fulfillment of his dream. A few months after the foundation he left Egypt for the East and never returned. Alexander�s death led to a power struggle from which his general, Ptolemy emerged victorious and went on to found a line of rulers. The early Ptolemies kept order and fostered the development of the Library of Alexandria into the leading Hellenistic centre of learning, but were careful to maintain the distinctions between its population's three largest ethnicities: Greek, Jewish, and Egyptian. Alexandria may have been an Egyptian city but the Greeks were firmly in charge and made every effort to preserve and study Greek culture and to suppress whatever came from non-Greek sources. The Greeks looked down on the Egyptians and one Alexandrian poet referred to them as �Muggers�.

This little fragment of history is important because, in spite of the official Greek disdain for the work of those whom they considered inferior, there was in fact a fusion of Greek, Hebrew and Egyptian wisdom, as appeared notably in the hermetic tradition that we discussed last week. So now we shall see what kind of impulses came out of Greece to join in the alchemical stream, and see what it was about the perceptions of the Greek philosophers that made alchemical transmutation seem quite a reasonable idea. Perhaps the first thing to grasp is that these people were working at the time when the descent of the cosmic intelligence and a further step in the withdrawal of the divine powers had only just begun.

We are so used to experiencing our thinking as a process that we control, and our thoughts as our own that it is hard not to assume that this has always been so. Business records preserved from ancient Egypt seem to have been compiled out of a mercantile frame of mind not so very different from that of nineteenth century England. From the Babylonian astronomers to the Greek mathematicians the practical handling of number and geometrical form was conducted in ways that appeal very much to the modern consciousness, and it is easy to overlook the metaphysical excursions and spiritual intimations of those whose perceptions took them beyond the transactional world. And yet the whole flavor of the ancient civilizations is quite removed from anything that we experience today. The objects of everyday experience were physical, certainly, but not merely physical. Thoughts were not merely about the objects of perception but were perceived as belonging to and inherent in those objects. Ancient Greeks who had been initiated into the Mysteries, as Rudolf Steiner tells us, were conscious of the spiritual beings who had stewardship of the workings of nature. The following is drawn from a lecture cycle called The Driving Force of Spiritual Powers in World History, which was given in 1923.

�If an ancient Greek had wanted to account for the origin of his thoughts through knowledge of the Mysteries, he would have had to say the following: I turn my spiritual sight up towards those beings who, through the science of the mysteries, have been revealed to me as the spirits of form [Exousiai]. They are the bearers of cosmic intelligence; they are the bearers of cosmic thoughts. They let thoughts stream through all the world events, and they bestow these human thoughts upon the soul so that it can experience them consciously.�

Steiner goes on to describe how, in a process centered in the fourth century AD and reaching completion in the fourteenth, the Exousiai gave up their rulership of the cosmic intelligence to the Archai � the Principalities � one step closer to the human being. At the same time the Exousiai maintained their stewardship of the whole world of sense impressions � colors, forms and sounds. The ancient Greek had perceived the angelic thought-forms streaming from natural objects. During the time of which we are speaking this capacity gradually disappeared. In earlier times people had experienced the thoughts and the actions of the hierarchies as part of their perception of the natural world. Now thinking would come to be an inner experience, while sense perceptions would still be felt as something external.

Since Steiner tells us that the whole process of the descent of the divine intelligence was centered on the fourth century AD and completed by about fourteenth we must conclude that the change began in the seventh century BC and extended over the period that he called the Age of the Intellectual Soul, or the Fourth Post-Atlantean Age. Its completion accounts for the growing feelings of independence and self-confidence with which Renaissance people tackled the problems of the world around them. The timing of its inception helps us to understand the first stirrings of the impulse to develop objective and logical explanations for the phenomena of the natural world, which appeared in Greek civilization two centuries before the Golden Age of Greek philosophy, the age of Plato and Aristotle. To get a bearing on this we can note that Plato was born in 427 BC and that Aristotle died in 322 BC, nine years after Alexandria had been founded by his most illustrious pupil. It is often said that Greek philosophy began in 585 BC when Thales correctly predicted a solar eclipse � more than a hundred and fifty years before the birth of Plato. Predicting an eclipse was not such a big deal, however. Babylonian astronomers had been doing that sort of thing for centuries.� The real change began when people like Thales started asking questions like, �How and why did the world begin, what is it made of and how does it work?� This desire to know the truth about things is one of the characteristics that make human beings different from other sentient beings, but we mustn�t simply assume that the early Greek philosophers were just like present day scientists, only less well equipped and informed. They were living through the earliest stages of a great transition in which the newly emerging relationship to thinking did not abruptly cut off their sense of the divine, as is clear from the spiritual perceptions still evident in their work, and the difficulties they got into. It is also clear, however, that there was to be a new relationship to spiritual matters. It no longer seemed satisfactory to answer questions about the world processes in terms of the creative deeds of the gods. Many of these stories came down from Homer and Hesiod, who lived at a time when the ability of human beings to perceive the working of spiritual powers had already waned greatly. It is therefore understandable that some of the activities of the Olympian�Pantheon do not seem particularly godlike to us and many of the stories have reached us in corrupt forms. Xenophanes�of Colophon, a younger contemporary of Thales, complained that �Homer and Hesiod attributed to the gods all the things that among men are regarded as shameful and blameworthy � theft and adultery and mutual deception�. He actually rejected the whole pantheon of gods in favor of a single great god who perceives and works through the sheer power of thought, and he was not alone in doing this. The early philosophers may have disagreed radically about the nature of existence, but they were�generally clear that it is lawful and that its processes can be understood. History is not a one-damn-thing-after-another sequence of unrelated events and nature is not just a playground for a troupe of whimsical gods. The very word, Kosmos, used by Heraclitus�where we would say Universe, means an arrangement that is not only orderly but beautiful too. This does not mean that the Pre-Socratic philosophers were atheists � only that they wanted nature to be self-explanatory and God, or the gods, to be rational and not interfere too much.

In their scientific work they struggled particularly with two problems that were fairly new to human experience: one was the question of the relationship between what�s out there and what�s in here � in other words, between the world of our sense perceptions and that of our thinking. Is one more real than the other or can we somehow make them cooperate? At the risk of considerable over-simplification we can say that one pole was represented by Parmenides, who, as Steiner puts it, was surrounded by a wall of thought and believed that the varied and ever-changing face of nature was an illusion. The opposite pole, or something very much like it, was expressed by Heraclitus who seems to have gloried in nature�s transience and contradictions. The other question, closely related to the first, was the problem of giving some unity to the apparent diversity of the world and one of the answers to this latter question came in the form of the idea that all the diversity comes from the transformations of a primal substance. Thales believed that all the different substances in the world are transformations of water, but he also believed that soul is mixed with everything and that the universe is full of gods. His contemporary, Anaximander, another Milesian, spoke of an unfamiliar basic stuff, infinite and indefinite, from which all familiar substances derive. Anaximenes, Anaximander�s pupil, thought that the infinite stuff from which everything came into being was air. Condensation generates winds, clouds, rain, hail and earth. Rarefaction yields fire. Fifty years or so later, Alcmaeon, the physician, wanted to explain everything in terms of pairs of opposites: hot and cold, light and dark, wet and dry.

Xenophanes�seems to have taken earth as the primal�substance and Heraclitus�(fl. 500 BC), made fire his principle. Heraclitus was known as the �obscure� and the �riddler�. Even Socrates found him puzzling. It is said that when Euripides�gave him�a copy of Heraclitus� book and asked him what he thought of it, he replied: �What I understand is splendid; and I think that what I don�t understand is too � but it would take a Delian diver to get to the bottom of it.� The following little sample explains why and also illustrates the difficulty of understanding the pre-Socratic philosophers in modern terms: �Heraclitus says that the universe is divisible and indivisible, generated and ungenerated, mortal and immortal, Word and Eternity, Father and Son, God and Justice.� It is no wonder that Socrates was baffled and Parmenides, like Averroes[1]and Aquinas�more than a millennium and a half later, felt it necessary to state quite forcefully that contraries could not be simultaneously true.

Empedocles, who died only a few years before Plato was born, imposed some order on this mass of conflicting opinions by attributing the multiplicity of nature to the combinations of four elements, or roots, - earth, water, air and fire - characterized in terms of some of Alcmaeon�s opposites � hot and cold, and wet and dry. This system was accepted by later philosophers and is what most people think of when �the Greek elements� are mentioned. We must be careful not to assume that the word �element� meant the same to Empedocles as it does to a modern scientist. To some of the Greek philosophers, it seemed that the elements in different substances and in the world as a whole are held together by love�and torn apart by strife. To say, as some modern people have, that love simply means a force of attraction and strife a force of repulsion, is to assume na�vely that the ancient Greeks thought in exactly the same way as the nineteenth century scientists but had odd, fanciful ways of expressing themselves. At the same time it has to be recognized that among the early philosophers there were some who showed a strong streak of materialism. The most obvious example is Democritus, whose atomic theory was an attempt to solve some of the most intractable problems of early Greek philosophy, but this tendency also appeared in the writings attributed to Hippocrates, the physician, who lived in the fifth century BC and rejected supernatural explanations of diseases. It took the combined efforts of Plato and Aristotle to give some unity to the philosophical mixture and to provide a new starting point for the study of everything, including physics, medicine and all that went into alchemy. For the alchemists the ideas of potential, growth, transformation, generation and dissolution were very important. That which was not present in actuality may be present in potential and this is the basis for genuine attempts to transmute base metals into gold.

One of the key ideas that Aristotle accepted was belief that metals grow inside the earth. It was believed that less perfect metals, like lead, are slowly transformed into more noble metals, like gold. Nature performed this cookery inside her womb over long periods of time � it was for this reason that, during the Middle Ages, mines were sometimes sealed so as to allow exhausted seams to recover, like fields allowed to lie fallow, and for more metals to grow. The alchemists wanted to find ways of repeating Nature's process in the workshop in a much shorter time. The four element theory made it seem that there was no philosophical or scientific reason why one metal should not be transformed into another � it was just a question of finding the technique. One such proposed method was based on a misunderstanding of Aristotle�s concept of prime or unformed matter, which, as we saw, went all the way back to Anaximander. Aristotle had not thought of this as a tangible stuff that would be left if the form of a substance was destroyed, but that is how some of the alchemists viewed it, as in the following proposal for creating gold, which springs from the idea that there is a strong working analogy between the processes of organic nature and those by which metals are generated.

There is a cycle of death and regrowth in Nature from the seed, its growth, decay to its regeneration once more as the seed. So working by analogy, the alchemist can take lead and 'kill' it to remove its form and to produce the primary, unformed matter. This then acts as a compost on which to grow the new substance. The form of gold is impressed by planting a seed � presumably a small particle of gold � on the unformed matter. To grow this seed, warmth and moisture were needed, and so were various kinds of apparatus � stills, furnaces, beakers and baths.

������ That was just an example of the way in which the metallurgical branch of alchemy was permeated by Greek ideas. For reasons that varied from the noble to the commercial the alchemists developed a secret language which concealed their knowledge from the uninitiated, a language that became more and more picturesque and fanciful. You may be puzzled to read that �The grey wolf devours the King, after which it is burned on a pyre, consuming the wolf and restoring the King to life�; but all becomes clear when you realize that this refers to the extraction of gold from its alloys by skimming off the sulphides of lesser metals formed from a reaction with antimony sulphide, and the roasting of the resultant gold-antimony alloy until only gold remains. Metallurgy in general, and efforts to transmute base metals into gold in particular, may have been the most famous and sometimes notorious activities of the alchemists, but among the Greeks pharmacy was of equal importance. They mixed, purified, heated and pulverized minerals and plants to make salves and tinctures, and it seems that medicine and pharmacy combined with metallurgy to form the mixture that gradually made its way into Western Europe under the name of alchemy. Many influences, some of which we discussed last week, came together to strengthen the belief that transmutation was really possible, but artisans continued to find methods of making products that were in some cases honest imitations of gold and in others pieces of real fakery. Genuine alchemists severely criticized goldsmiths for making imitations when if they had been properly educated in philosophy they would have known that actual transformation was possible.

����������� Possible it may have seemed, and much that might metaphorically be understood as transmutation occurred, but for many the desire to produce actual, visible, wearable and saleable gold displaced the spiritual aspirations that had always been part and parcel of alchemy. And while this desire was never satisfied, the rogues and charlatans made a good living and gave the Sacred Art a bad name. Many unscrupulous practitioners took advantage of the ease with which transmutations could be simulated and of the gullibility and cupidity of their victims, and their methods even found their way into some of the chemical manuals published in Alexandria. Here, as a little comic relief, are a few examples.

�Here is a typical recipe from a handbook compiled in about 200 BC, from which we gather that Archimedes� principle had not yet reached Hellenistic Egypt.

�One powders up gold and lead into a powder as fine as flour, two parts of lead for one of gold, and having mixed them, works them up with gum. One covers a copper ring with this mixture and then heats. One repeats several times until the object has taken the color. It is difficult to detect the fraud, since the touchstone gives the mark of true gold.�

Another deception was to take a nail, half of iron and half of gold, and cover it with black ink. It was then dipped in a special liquid � well, water is a special liquid � when the black was washed away and the part of the nail dipped in the liquid apparently turned to gold. This led to the sale of some very expensive water. Still another trick was to take a coin made from a white alloy of silver�and gold and dip it in nitric acid, when the silver was dissolved and half the coin apparently turned to gold. Some of these coins are still in museums�2

I�m sure you�re all familiar with Murphy�s First Law, which states that if something can go wrong, it will. Murphy�s Second Law is less well known but equally ineluctable: it tells us that whenever there is an opportunity for fraud someone will pounce on it. The history of alchemy, like the histories of politics, big business, religion and most other human pursuits, is riddled with fraud. In the nineteenth century, while the spiritual aspirations of genuine alchemists were being to some extent honored, atomic chemistry offered some hope not only to those who thought that transmutation might after all be possible but also to those who spotted the possibility of a quick scam. Evidently the evolution of consciousness has provided con artists with more highly developed methods while not making us any less susceptible to their wiles, as is evidenced by the alacrity with which people send the details of their bank accounts to strangers in far countries who promise to deposit large sums of money in them. In the 1860�s a Hungarian refugee named Nicholas Papaffy perpetrated a daring swindle on the London Stock Exchange, duping a large number of investors into supporting a scheme for transforming bismuth and aluminum into silver. After a public demonstration of his method, the new company�s offices in Leadenhall Street were opened, only to reveal that Papaffy had absconded with �40,000, which was a lot of money in those days. And before you make any wisecracks about the gullible Brits you should know that thirty years later the American government bought a bunch of gold ingots from an Irish-American metallurgist called Stephen Emmens, which he claimed to have made from silver by his �Argentaurum Process�. And, by the way, in view of the state of the construction market, I could probably get you a good price on the Brooklyn Bridge�

Well, back to more serious matters.

Like many other scientific and philosophical impulses, Greek alchemy was taken up by the Arabs and came strongly into Western Europe in the eleventh century, through translations of Arabic texts. The Arabs were familiar with Indian and Chinese alchemy and it is through them that the ideas of the philosopher�s stone and the elixir of life made their first appearance.

There is no doubt however, that the true alchemical quest to perceive and understand the spirit in nature and in the human being had a life of its own and had been going on in mediaeval Europe long before the Arabian impulse arrived. Last week I made a brief reference to Steiner�s description of the plight of the mediaeval alchemist, who knew of the tradition of the cosmic beings, the architects of human evolution, and who was still in contact with the nature spirits. These earthbound spirits could tell him much about the spiritual world but could not make contact with the great spirits possible. And, in Steiner�s words, they would not speak about reincarnation � they had no interest in repeated earth lives. So the alchemists worked in an atmosphere of sadness and Steiner gives an example of the kind of physiological research that they undertook. This comes from lecture 13 of a cycle on the Mystery Centres given in 1923 and it gives a wonderful insight into what I was saying last week about the difference between the way people experienced nature in pre-renaissance times and the way we experience it now.

After speaking about the extraordinary kinds of consciousness found in beehives and ant-hills Steiner talks about oxalic acid, which is found in the clover much loved by the bees, and formic acid which is found in the ant. He notes that in the lab it�s quite easy to transform oxalic acid into formic acid and carbon dioxide by heating it with glycerol. To us this is a simple chemical reaction but to the man of the Middle Ages things looked different. He would have agreed that oxalic acid is found in clover but would have insisted that it is be found to a certain extent in the whole of the human organism, especially in the digestive tract. Now the workings of the human organism exercise an influence on this oxalic acid similar to that which is exercised upon it in the retort through the glycerin. So there passes into the lungs, and into the air that we breathe, this transformed product, formic acid; and we then breathe out carbon dioxide. The human being, however, is not a piece of apparatus. The experiment simply shows in a dead way what exists in us in a living and feeling way. Without the oxalic acid we should be unable to live, for it is that which gives the etheric body its basis in our organism. And if we were unable to transform oxalic acid into formic acid the astral body would have no basis in our organism. We require not only the presence of the two acids but also the activity of transformation. This is one question which the mediaeval alchemist, standing before his retort, asked himself: How does the external process which I perceive in the retort or any other chemical arrangement take place in the human being?

This is the kind of attitude that should always have pervaded alchemical medical practice, but it would be idle to pretend that it always did, and, as we shall see later, Paracelsus, the great medical innovator of the early sixteenth century, certainly didn�t think so.

*

Last week someone asked me if I would talk about the metals. This is an enormous topic, but as an introduction to Paracelsus I�ll say something about mercury and its frequent companion, sulphur. There is some appropriateness about this, since the god Mercury is generally considered to be the Roman equivalent of the Greek Hermes and Hermes is the Greek equivalent of the Egyptian Thoth, the representative of the gods who in the ancient world gave humanity its impulse towards the scientific exploration of nature. The substance mercury is very mysterious; out of the ninety or so naturally occurring elements in the periodic table it is one of only two that are liquid at ordinary temperatures. In its quicksilver fashion it runs through the whole history of alchemy. The name quicksilver or chutos argyros goes back at least as far as 300 BC, when it was mentioned by Theophrastus, who also remarked that it can be made by rubbing cinnabar with vinegar in a copper vessel. Later the name became hydor argyros and this was Latinized into hydrargyrium, liquid silver, which gives us its chemical symbol Hg. Later it was renamed after the messenger of the gods, nimble, volatile mercury, and given the same symbol as the planet mercury, the caduceus or herald�s wand. The chief ore, cinnabar, is a compound of mercury and sulphur, and mercury deposits are usually found along the lines of profound volcanic disturbances. The great quicksilver mine at Almaden in Spain is said to have been worked at least as long ago as 415 BC and according to the Roman historian Pliny, writing in 77 AD, 10,000 lb of cinnabar were imported annually from this source. This would have yielded about four tons of mercury, and it is not at all clear what the Romans used it for. Cinnabar itself is a bright red, crystalline form, used as a pigment under the name of vermillion and sometimes in the ancient world as a cosmetic. The ancient Chinese alchemists used the blood-red cinnabar therapeutically, believing that it might be transmuted into gold and that consumption of liquid gold would lead to immortality. It is on record, however, that this kind of chemistry fell into disrepute since its effect was often the opposite of what had been intended. In mediaeval Europe the Summa Perfectionis, a hugely influential work dating from the tenth century, and Arabian in origin, introduced the mercury-sulphur theory of metallic composition, which had its original basis in Aristotle�s view that metals grow in the interior of the earth. It includes the idea that metals are held together by a spirit, mercury, and a soul, sulphur. Like the older four-element theory, this fostered hope that metals could be transmuted, especially since the Summa explained the formation of different metals in terms of differences in the packing of the particles of the two substances. Such ideas were strengthened by the ability of mercury to dissolve other metals and form amalgams like the silver amalgam that some of us have in our teeth. The transformations of metals were ascribed to the influences of a mercurial agent that later became known as the philosophers� stone, about which Rudolf Steiner had other ideas. Most people believe that the philosophers� stone and its magical powers are unreal fantasies of the mediaeval mind, but there is one story from a witness whose testimony about other matters has been considered reliable � the great Belgian chemist Jan Baptista van Helmont, who was born in 1577 and became an ardent follower of Paracelsus.

Van Helmont�s work was strongly influenced by alchemy and he was convinced that, with the help of a tiny quantity of the philosophers� stone, given to him by a stranger, he had transmuted mercury�into gold. The philosophers� stone was a �heavy red powder, glittering like powdered glass and smelling of saffron; it was enclosed in wax and projected on mercury heated to the melting-point of lead, when the metal grew thick, and on raising the fire, melted into pure gold.� It is fortunate that van Helmont was not interested in the commercial value of the process, since it took nearly 2000 grains of mercury to produce one grain of gold. The heavy red powder sounds very much like purified cinnabar or, just possibly mercuric oxide, and if we want to be skeptical we can simply assume that the stranger had concealed a particle of gold in it. But we don�t have to; van Helmont was a very experienced chemist. As a footnote to this story it may be worth noting that in 1980, a sample of bismuth was transmuted into one-billionth of a cent's worth of gold by means of a particle accelerator at the Lawrence Laboratory of the University of California at Berkeley. The cost of producing this minute particle of the king of metals was $10,000, so looked at financially, the return was much worse than van Helmont�s.

Paracelsus, who was born around 1493, took up the tradition of mercury and sulphur as the basic formative principles of matter, and added the principle of salt to form what became known as the tria prima, to which Rudolf Steiner attached such great importance. This evening I�ll give you the briefest of introductions to Paracelsus and his work � next week we�ll have a little more detail and we�ll see how he became a very important influence in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Paracelsus may well have been the archetypal choleric. One of the most famous stories about him relates how he rebelled against the traditional medicine of his day and publicly burnt the works of Galen and Avicenna with sulphur in a brass dish and proclaimed his wish that the authors were in like circumstances. It is an unfortunate fact the most of the details we have of his life as a young teacher in the University of Basel come from a man who had every reason to paint as dark a picture as possible. After his forced and undignified retirement from Basel he worked as a military surgeon and itinerant physician throughout Europe and his major preoccupation was the study of the nature and therapeutic uses of plants and minerals. Rudolf Steiner had several reasons for regarding Paracelsus as an important figure, one of which concerned his attitude towards the study of nature, which enabled him to avoid the wiles of Ahriman and the charms of Lucifer.

�One who does not look beyond natural processes may be left cold by them as by things of a material and prosaic nature; one who at all costs wants to grasp the spirit with the senses will people these processes with all kinds of spiritual beings. But like Paracelsus, one who knows how to look at such processes in connection with the universe, which reveals its secret within man, accepts these processes as they present themselves to the senses; he does not first reinterpret them; for as the natural processes stand before us in their sensory reality, in their own way they reveal the mystery of existence. What through this sensory reality these processes reveal out of the soul of man, occupies a higher position for one who strives for the light of higher cognition than do all the supernatural miracles concerning their so-called �spirit� which man can devise or have revealed to him. There is no �spirit of nature� which can utter more exalted truths than the great works of nature themselves, when our soul unites itself with this nature in friendship, and, in familiar intercourse, hearkens to the revelations of its secrets. Such a friendship with nature, Paracelsus sought.�

Next week I�ll talk some more about Paracelsus and see how his work and that of other alchemists deeply influenced many of the scientists of the seventeenth century, notably Isaac Newton. Finally I�ll try to show how what was good and noble in alchemy fed into the scientific work of Goethe and Rudolf Steiner.

[1] See Averroes: On the Harmony of Religion and Philosophy. Tr. and ed. G. F. Hourani; Luzac, London 1976

[2] These items are quoted from J. R. Partington: A Short History of Chemistry.

Lecture number 3 will appear in the next issue of SCR

Keith Francis was educated at the Crypt School, Gloucester, England and at the University of Cambridge. He worked as an engineer at the Bristol Aircraft Company before returning to the Crypt School as a teacher of physics and mathematics. In 1964-65 he studied at the Waldorf Institute of Adelphi University, Garden City, New York and later joined the faculty of the Rudolf Steiner School in Manhattan, where he remained until his retirement in 1996. Since then he has written several novels, a memoir of his experience as a Waldorf teacher, a somewhat controversial assessment of the work of Francis Bacon and a history of atomic science. He is also the founder and director of the Fifteenth Street Singers, a group attached to the New York City Branch of the Anthroposophical Society. He has been a member of the Anthroposophical Society since 1962.