My motoguadaña broke down. (I don't know what it's called in English; literally it would be a motor-scythe, but that doesn't sound right.) So I had to take it to Villa Dolores, the nearest thing in the Traslasierra valley to what could be called a city. It's about 20 kilometers from where I live. I go there ever Wednesday anyway for a massage, so this was killing two (or more, as you shall see) birds with one stone. I loaded it in my car – a 1995 Fiat Siena - with the motor on the left of the back seat and the rest crossing diagonally over the seats and the cutting edge peeking out the right front window. At the entrance to Villa Dolores I unloaded it at the mechanic's tiny garage. When I explained the problem to him – the damned thing refused to start – he looked at me with his sad baggy eyes and nodded. One had to guess what that meant; he is, to put it mildly, a taciturn man. I told him I'd be back in about an hour, and he nodded again.

I drove farther into the heart of Villa Dolores, and stopped near my masseur's consultorio, which is actually a room she rents in an old house full of family photos going back many generations, musty old books and a doll dressed all in black with swords piercing her heart and...enough! It's Nuestra Señora de los Dolores (Our Lady of Pain!) Maricel, my Schaitzu friend, did a good job on my back and waist, which were beginning to bother me...again. While pushing and poking, she informed me that her beloved aged cat had died a few days previously. She gave it a Viking funeral (without the boat), adorning it with its favorite green collar and invoking all the religious incantations she knows, from the Hindu AOM to the Our Father, before burying it wrapped in costly stuffs. Despite knowing that this was a sad and solemn moment for Maricel, I couldn't resist asking her if she had also included a sword.

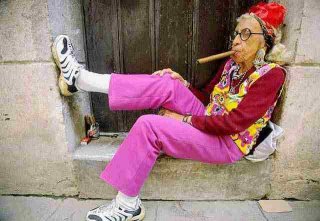

The Old Lady

Leaving Maricel, I turned left and followed the calle Erdman toward the Plaza and my bank. On the way I passed the Banco de la Nación, where a long line stretched along the sidewalk waiting for the ATM. Why anyone would willingly be a client of that bank is beyond me – unless they are state employees who are obliged to use it. Its efficiency is that of a moribund dinosaur. An old woman tapped along the line with a crude blind person's stick; I say crude because it was a cane with once-white tape wrapped around the bottom. In summer here everyone wears shorts (or miniskirts) and sandals, but she wore pink slacks and, despite the heat, a yellow vest over a long-sleeved sweater. Worn sneakers and a funny hat. I couldn't tell if she was looking for the ATM or trying to pass it. After she passed the first person on the line, brushing his ankle with her cane, she tapped the wall of the bank, looking confused. By that time I had come abreast and asked her if she was going to the corner. She turned and “looked” at me as blind people do, not quite hitting the target.

“Yes,” she said, and took my arm without my having offered it. “People are in such a hurry nowadays,” she said. I realized that I was pulling her along a bit, so I relaxed into her baby steps. We stopped at the corner. I asked where she was going.

“To the clinic,” she said. I assumed she meant the shabby medical center located about a half a block down to the left. “Bueno,” I said, and tried to turn left but she didn't budge. “Are you going that way?” she asked me, her eyes pointing up over my head.

“It doesn't matter,” I said, “let's go.”

“But are you going that way anyway?” she insisted on knowing,

I wasn't, but I sighed inwardly and said yes. So we turned left and shuffled cautiously along like a pair of snails, the lady hanging heavily on my arm. She started talking then, that she was a widow, something about her son, but I couldn't hear her well because of the motorbikes buzzing down the street like loud-mouthed mosquitoes.

When we reached the clinic I opened the door for her, but we had to squeeze through together because she still clung to my arm. There were a couple of steps to navigate and when we did I asked her if she wanted to go to the reception counter. No, she wanted to go to the waiting room, which isn't a room, but a row of plastic chairs across from the receptionist. I led her to a chair and placed her hand on its back.

“Well”, I said, “good luck”. She held her hand out so I took it to shake. She asked me where I live, I told her and she said she knew a nurse there. “Oh? What's her name? She had to think a while then said the name of someone I don't know. She still held my hand and I realized that she wanted nothing better than to sit there talking to me for as long as it took. "Do you smoke?" she asked. "Yes", I replied, "a pipe." "Oh, then you probably don't have a cigar on you." "Sorry, no." I extracted my hand, said goodbye and fled.

As I walked along toward my bank, I somehow felt good at having done a good deed. But then: Why do I feel good about something that Boy Scouts do, or should do, all the time? It didn't cost me anything except a few minutes of my time, something which only I consider valuable. Perhaps because it's such an exception, when it should be routine.

The Bank

At the Banco Macro (which here only means big and has nothing to do with the macrocosmos) only a boy about 5 years of age was on line at the ATM. He was a line of one perched on a metal railing swinging his feet and conscientiously watching them. “Hola,” I said to him, “taking much money out of the bank?”

He looked up from his feet to me with those wide-open global eyes kids have when they're surprised or don't understand, or both. At that moment a man exited the ATM booth and walked away. I entered. A young woman was clicking away at one machine and I used the other. We finished at the same time, but she was closer to the door and opened it for me. I put a hand on it, holding it open, smiled and said “After you”. She smiled back, exited, the boy hopped down from the railing and put his hand in hers. As they walked off he turned his head and looked up at me and said: “Ciao”. I waved and said ciao back and saw him talking to his mother as they rounded the corner, surely telling her about the funny thing that old guy said to him.

The Café

My next stop was the Bonafide café for a double expresso cortado (with a dash of milk) and a brownie (brownie

in Spanish). This meant walking diagonally across the Plaza, which is a full block square of leafy trees, flowers in bloom and kids running and jumping around expending energy. In my mind I saluted the statue of old Bartolomé Mitre as I passed him (ironically I fear) and walked a few blocks along Avenida Belgrano, another independence hero. (Someone said that Argentina is full of monuments to people no one ever heard of.)

I sat outside in the relatively cool...well, not so hot...late afternoon, had my coffee and brownie and was reading the book I'd taken along for this moment: Underground by Don DeLillo. I not only do not recommend it, I recommend that you refrain from trying to read it. It's overlong and tiresome. The author seems to have intended writing a modern Ulysses. The only thing that kept me at it is the first chapter, which is about a baseball – the one Bobby Thomson of the NY Giants hit off Ralph Branca of the Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1951 playoffs. The idea is that a black kid gets it and then loses it, it gets into other hands, then is supposed to be the thread that keeps the rest of the book going. But the baseball unravels early on, as does the book.

Suddenly I heard a voice next to me: “Excuse me. Are you from here?” I looked up and saw a guy about 30 years old standing there in shorts and a t-shirt, kind of swarthy and stocky with a broad grin on his face. Beautiful teeth.

“Yes,” I said. This often happens, but only after I talk for a while and people notice my accent. But this guy only looked at me – and I don't look much different than many Argentinians. But maybe he also saw the title of the book.

“Oh, wonderful. I saw your t-shirt and thought that maybe you're from Florida.”

I was also wearing shorts and my t-shirt bore a cool colorful design: Palm Beach – Florida. “Oh, I see what you mean,” I said. “Actually I bought this in Florida.”

That was his opening. “I'd love to go to Florida some day. Do you speak English?” I thought of those scam artists in Buenos Aires: “Pardon me, do you speak English? I am Swedish sailor and I missed my ship. I wonder if you could lend me some money until some arrives from home.” But no, this is the very provincial Villa Dolores, not cosmopolitan and crooked like Buenos Aires. Furthermore, passers- by were greeting my new interlocutor; he was obviously well known here. I told him that I did indeed speak English.

“Ah. And you live here in Dolores?”

“No, in Las Chacras.”

“How beautiful. Some day I would like to live between Nono and Mina Clavero, near the river.”

“Yes, they have water there,” I agreed, realizing that if I wanted to get rid of this guy I'd have to insult him. “Have a seat,” I said instead, motioning to the chair across from me.

“Ah yes.” He was eager to comply. “But just for a minute.”

“Where did you learn English?” I asked him slowly in English.

His eyes opened wide, like that kid's in front of the bank. Then, when his neurons had processed the information, “Here, in Villa Dolores...but then... I am young guy.”

“I was a young guy,” I corrected.

“Ah yes, I see. Thanks.”

We conversed for about ten minutes in English. His was very bad, but he was totally without inhibitions, so a conversation was possible. When we reverted to Spanish he was sweating at the effort. He (Fernando) is a d.j. at what he called “nightclubs” (discos) – of which there are two in Dolores and a neighboring town – and he offered to present me with a cd of “new” music. I didn't say no, but he may have detected a lack of enthusiasm. We parted friends.

The Mechanic (again)

I drove back to the garage to see if the mechanic had been able to repair my motoguadaña. He looked up from something else when I entered. “Hi, how's my machine?” He nodded, which I interpreted to mean it's fine. He took it from where it was resting with relatives and walked out with me to the street. “Carburetor blocked,” he said. “Where do you buy gas?” I told him in Villa de las Rosas, near where I live, and which has one service station. “Don't buy it there,” he said. “Villa Dolores is better.” He carefully placed the motoguadaña in my car.

“What do I owe you?” I asked him.

“Nothing,” he said and patted me on the shoulder. “You were here a month ago. Our work is guaranteed.” He shuffled off, nodding.

The Service Station

Taking seriously what the mechanic said about not buying gas in Las Rosas' only service station, implying that it is contaminated, I stopped at the Shell station in Villa Dolores. The “motos” from China – not quite motorcycles but bigger than the Italian Vespas – have become a plague here, and from what I see on TV, the third world in general. So service stations here often have a special line for them – not to give them better service, but not to delay the real customers, the automobiles. I pulled up to a pump and was waited on immediately. We have not yet succumbed to the first world automated gas service. Human beings still work in service stations and pump gas.

A young man filled up my tank and proceeded to wash my windshield.

“In all the years I've lived in Traslasierra,” I said to the attendant as he worked, “this is the first time anyone has ever washed the windshield. I always wondered why. I mean if you wash the windshield you're sure to get a tip – and tips add up.”

He smiled as he walked around to the back to do the back window. “They're lazy, that's all,” he said. “No other explanation. Where are you from, señor?” Here we go again.

“From the most powerful and stupidest country in the world,” I said. “Guess.”

“The United States,” he said with no hesitation. “I have an uncle in Con-nec-ti-cut. He wants me to go there to help in his business, but I don't want to.”

“Visas are complicated nowadays,” I said.

“Yes, but it's not that. I just want to stay here.”

He finished and I gave him 5 pesos, the equivalent of a $1.50 tip, for which he thanked me profusely, and would have been thrown out the window of a N.Y.C. taxi.

It was no Odyssey, but all in all not a bad day.