The

Holocaust in Cambodia

By

Julie Masis

PHNOM PENH - The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC plans a new exhibition on Cambodia's Khmer Rouge, but it is uncertain if the American secret bombing of the country, which some analysts say helped the radical Maoists come to power, will be included in the presentation.

The temporary exhibition, which is scheduled to open in the next 12 to 18 months, will feature photographs, video footage and artifacts from the Khmer Rouge regime that some estimate is responsible for the deaths of approximately two million Cambodians between 1975 and 1979. The exhibition will also discuss the ongoing United Nations-backed Khmer Rouge tribunal.

The exhibition will be in line with the museum's mission of preventing genocides around the world, said Michael Abramowitz, the director of the museum's Committee on Conscience, who recently visited Cambodia with an 18-member delegation from the United States. It is also being viewed as part of the US's ramped up diplomacy in Southeast Asia in line with Washington's "pivot" towards Asia.

"We want to study these genocides so that we can do more to prevent these genocides from happening again," Abramowitz said. "We want to make it clear that genocide didn't stop in 1945."

While the Holocaust Museum's primary focus is on the Nazi crimes during World War II, the museum has also held small displays on genocides in Rwanda, Sudan and Bosnia, Abramowitz said. It will be the first time that the museum, which is funded by the American government and receives more than a million visitors every year, will hold an exhibition on an Asian genocide. According to its website, the museum has received more than 34 million visitors since it opened in 1993, including 91 heads of state.

Contested role

The museum delegation, including former US secretary of homeland security Michael Chertoff, Illinois State Senator Jeffrey Schoenberg and CNN journalist Amy Kaslow, visited the infamous Tuol Sleng prison, where the Khmer Rouge murdered an estimated 17,000 people. The delegation sat in on a session of the Khmer Rouge tribunal, interviewed survivors, and spent an afternoon watching an interview with former Tuol Sleng prison chief Kaing Guek Eav, or Duch.

The delegation also met with Youk Chhang, director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, which holds the world's largest archive of documents related to the Khmer Rouge. Chhang, who is a survivor of the Khmer Rouge regime, brought the Americans to see a pond in a picturesque village outside of the capital. The 10-meter-deep pond in Kampong Chnang province, he explained to the visitors, was left behind by an American bomb.

"When the villagers began to tell the story, it was chilling," Chhang said. "They picked up the remains of the bomb [and sold them] to make a living. They all know this site, and they don't drink from this pond."

More than two million tonnes of American bombs were dropped on Cambodia between 1965 and 1973 as part of the wider war in Vietnam. Some of the secret bombing campaigns were referred to crudely by government officials as "breakfast", "lunch", "dinner", "snack", and "desert", according to an article co-authored by American history professor Ben Kiernan, who is also author of the book How Pol Pot came to power.

The American-dropped bombs resulted in the deaths of between 50,000 to 150,000 people. Some analysts, including Kiernan, say that these civilian casualties drove angry villagers to support the Khmer Rouge, who generally were not popular at a grassroots level until the bombing began. The Khmer Rouge forces grew from only 10,000 in 1969 to more than 200,000 by 1973.

Abramowitz said he cannot say with certainty if the American bombing of Cambodia will be included in the museum's display. The problem, he explained, is that exhibitions tend to be small. "There is a huge amount of information that we have to boil down to a very modest [presentation]," he said.

He added that the exhibition will discuss the role America played but not necessarily the bombing. "We do plan to touch on the American role, which will be of interest to our visitors," he said. "If you study Khmer Rouge history, America is very much tied in - [We might discuss] the American role in trying to broker the Paris peace accord in the 1990s. America is [also] a strong supporter of the [Khmer Rouge tribunal]."

Select presentation

Even if the American bombing of Cambodia is included in the exhibition, there are many ways the museum could choose to present the campaign. For instance, it could also be argued that American bombing actually delayed the Khmer Rouge victory by supporting the right-wing government in Phnom Penh.

"It's a long debate, but I'm sure the Holocaust museum will give a balanced [view] to the public," Chhang said. "The US publicly apologized for one bomb and compensated the victims who lost their family members. This can also teach us about forgiveness." The Documentation Center of Cambodia has already helped to organize several Khmer Rouge exhibits in the US, but almost all were on university campuses, according to Chhang.

While in Cambodia, Abramowitz said he saw strong parallels between the Holocaust and the Khmer Rouge regime. While attending a session of the Khmer Rouge tribunal, for example, he heard testimony from a former railway company employee about the evacuation of Phnom Penh in 1975 when all residents, including hospital patients, were forced to leave the city at gunpoint.

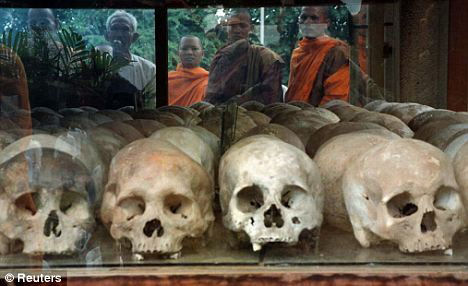

While Abramowitz did not say what kinds of artifacts will go on display in Washington, most of the Khmer Rouge memorials in Cambodia include the skulls of victims. These skulls, some with wounds that graphically illustrate how the Khmer Rouge murdered their victims, have never been included in any international exhibitions, Chhang said.

"I think the government would support [the museum] if they borrowed the skulls," he said. "Cambodia has a tradition of cremating the bodies, but according to our tradition, you cannot cremate someone who does not belong to your family." Because it is not known to whom the skulls of the Khmer Rouge victims belonged, they cannot receive proper burial. "For this reason, it's permissible to include them in an exhibition," he said. "The bones still speak."

Julie Masis is a Cambodia-based journalistThis article originally appeared in the Asia Times

Home