Un pu�o de tierra

by Michael McGuire

La gobernadora was known for keeping her peace.�

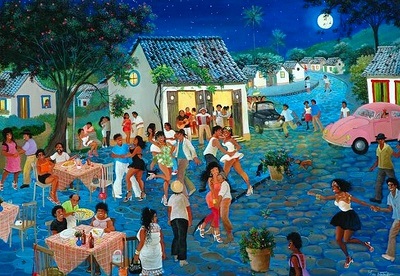

She sat soundlessly throughout the fiesta for her visiting sisters until the visiting mariachis from el Recreo, reputed to be one of the best in Mexico, reached the climax of their interlocked and uninterrupted pieces, when she released a roof rattling bramido from deep inside, one that seemed to bring a giant thump from the tarps stretched overhead for the occasion.� But it was only the boom of the wind which had, at last, heard the call to party.

Nevertheless, it was the sign for one of the young nieces, daughter of a wife of a man who was married to one of the sisters, to put down the bottle of tequila she had been insisting everyone knock back a trago from and drag unwilling dancers onto the floor.� The last she ventured to grab was la gobernadora herself.

La gobernadora was no longer governor.� But by some means she had retained the authority.� People paid her respect and whenever that respectful title was uttered, everyone knew who was being talked about.

Having settled into her own colossal body, after issuing her one and only grito of the night, and into the unutterable sadness that rises like a tide of dust near the end of every family reuni�n in these hills, in el cerro, she hesitated to accept the muscular pull of the soft warm hands of the niece.

What would she, la gobernadora asked herself, take in her hands and carry from this vale of tears?

Suddenly she joined the undulating crowd out from under the tarp and the couple of the same sex, if different eras, was dominating the dance, largely because la gobernadora required considerable room and was incredibly agile, both as a body of considerable capacity fore and aft--the gods of genetics had been generous with those commanding breasts, that authoritative bottom--and an unbound spirit within that body.� Even the strange, twisted one-eyed look she seemed to have at times, result, people said, of a premature stroke, for her ladyship was not that old, transformed itself during the dance into calculated concentration�as if she were taking the measurement of a world she had not quite conquered during her term in office, a world that was, in spite of everything, still there.

And, at times, when she resigned herself to the inevitable passing of power from her hands, into a kind of bliss.

The aforementioned niece had left the bottle of tequila in front of la gobernadora and, when the dance was done and the governor returned to her place at the head of the table, she made good use of it at times, even as the niece herself had demonstrated the technique, raising the bottle upside down to shake from it a stream that mostly found its way into her cavernous mouth.� And the voices of the mariachis echoed through the empty rooms of one unmarried sister�

La vida pronto se acaba

lo que paso en esta vida

nom�s el recuerdo queda

ya muerto voy a llevarme

nom�s un pu�o de tierra.

That seemed to answer the question.� She would take, not power and position from this life but, like a man shot in the back and falling forward, a fistful of earth.

Various parties embraced as the dancing ended. �The unutterable sadness rose and fell.� A kind of grief spread with the drinking.� Family and guests bonded in their sorrow. �Once more, as at unspecified if not quite unremembered moments in times past, the people of Pueblo Nuevo were together.

*

Though a river of tears might eventually find its way into the street, la gobernadora left the fiesta alone.� It seemed with her first, not quite bemused steps, that she heard a herd of horses in the distance, a sound unheard in Pueblo Nuevo for a hundred years, and so, though she listened a moment, she dismissed it and trudged on. And on.

She made her way through cold windy streets of brick and stone, left at the corner she had turned at since she could walk independently, up the hill and there he was.� In front of her.� Not some laggard she might have to kick in the ribs and send home.� Nor yet the phantom of recollected glory, the unforgotten trappings of office.�

Simply a dog, a street dog, a stray, but no ordinary creature.� For one, he dragged a length of chain so heavy it was inconceivable how it had failed to hold the animal.� More.� The dog had once been white, white as the ghost of a dog she�d once had. �But this creature was no longer white.� It had been graffitied.� Spray painted.� Not with the squiggles squirted on freight cars in the unimaginative north, but marvelously.

�de expresi�n artistica�

Leaning close to the once white cur who neither growled nor leered, but gazed up with a look of benign friendliness, la gobernadora saw, or thought she saw, in the adornment spurted upon it, not only the map of the street she was walking, but a rendition of her own small, squeezed house, with its own sweet scent of doom rising into the night.� It was all there.� In black and red on white.

�expresionista�

Masterpiece or not, to one side of her humble dwelling, as represented, drifted a dirigible of a soul, wheezing a child�s chubbiness: a floating mine, arms and legs extended at odd angles.

The moment la gobernadora recognized herself, naturally she listened for laughter and glanced in several directions the better to spot the guilty party.� El artista himself.� Nothing.� No one. �She stepped on the dragged chain and questioned the creature.

What does this mean, animal?� That I�m going home?� I know that.� That I�ll always be there, here, that I�ll never leave Pueblo Nuevo.� I know that too.� That I�m big as a balloon.� Is that supposed to be news?� Who did this to you, creature?� You didn�t do it yourself.� Come on!� Out with it.

Once more the look of benign friendliness, the upward glance of the forever mistreated.� Yet as la gobernadora looked down at the black and red and white beast of all breeds and of none, its branding of graffiti seemed to change before her eyes.�

She saw her mother somewhere between rib cage and collapsed stomach cavity, a woman who had been dead for years.� But there she was looking up at la gobernadora and, soft as her soft features continued to be, shaking her head.

You could have done better, m�hija, she seemed to say.� Any nitwit can play at power, take a dip in corrupci�n; it doesn�t take a genius to be on the take, but even the first female head of Jalisco could have found a moment to pair off and procreate.� Nothing is more important, m�hija, than children.

Once more la gobernadora looked around her.� Not for the above mentioned clutch of trailing offspring.� Not for a fluttering skyful of winged faces keen to nurse at colossal breasts.� That category was empty; her mother was right.� It was too late for that.� But to see if any passerby might have heard the same damning comment rise from a street artist�s version of her own dear mother or the animal�s inspired manginess.� What did la gobernadora see?

Nada.

An empty street corner on top of a hill.� The touch of an unseen yet inescapable wind.� A night after a party that could still be heard in the brief lulls as five sisters, minus one, hung upon each other�s shoulders and wept.� La gobernadora, satisfied she was alone, took her foot off the chain and pulled the mongrel close to her knee.

Are you male or female, critic�n? she asked and lifted the dog�s tail.� Aha!� I think, perro, under the circumstances I�ll take you home.� A female I would have left in the street.� A fifth sister doesn�t need any more females in her life.

El perro did not object.� He pattered alongside as if this were not the first time he�d accompanied la gobernadora to the house squeezed among others.

La gobernadora did not hurry over assorted bricks and cobblestones, through the cave-ins and pools of dust of the never-to-be-quite-repaired streets of Pueblo Nuevo.� Silently as her big feet might fall, soundlessly as the worn nails of her attendant stray might scuffle at her side, the two had added to the night the unavoidable clanking of a dragged chain and the feeling that there were more than two of God�s creatures in that darkness, more than the spirit of an unavoidable mother or the quivering cries, the winged faces, of never-to-be-born children� �There was, somewhere in that maze of shifting graffiti, a young girl staring into the future.

For la gobernadora had not been born la gobernadora.� Once� �She had been the child of promise herself. �The beautiful, the graceful, Graciela.

Once, before affairs of state had got her by her oversize whatevers and pulled her into a vulgar, vicious milieu of rake-offs and kickbacks, the dog-eat-dog world of personal profit, la gobernadora had read inveterately, she had studied languages and determined to be a devoted scholar.� An educated woman who would replace the misplaced identity of her race, mexicanas y mexicanos.� The literature of her time had not really, in spite of the critics� complications and simplifications, faced up to that which might face any people that was half this and half something else.

Who are we?� What are we?

The one question she might in time learn her mongrel did not like to hear was one she would raise after any indelicate if not tasteless misbehavior had been evidenced.

Just what kind of a dog are you?

At that her perro�s ears would flatten on his head as his eyes popped pink and apologetic up at her ladyship.

Please...� Any question other than that, and I�ll do my best to answer.

But it was not the dog�s story but the unavoidable fate of the beautiful, the graceful Graciela that was walking at her side.�

And this is it.

As a young woman who had had her taste of life in the colegios y universidades of her nation, had known power in the seat of her state�s governance and come home to a household of women, the males of several generations dead or gone, and, to create a little room for herself, had had constructed a small two room house between the house she was born in and one a couple of aunts were dying in, Graciela had determined, quite apart from the lemmings of her graduating class, city dwellers who clung to this, that, then the other thing, to go her own way.

Perhaps she would paint portraits that would evolve into likenesses of her underestimated and yet to be portrayed race.� Perhaps she would write works of polish and complexity, finding simplicity in intricacy or intricacy in simplicity (in a word, grace) that would rise unseen above the unseeing eyes of the editor in chief of the first circle, beyond the grasp of the slick fingers of the sales rep of the fifth.� Perhaps�

Here la gobernadora (or Graciela) stopped.� She had heard something beside a herd of unseen horses.� El perro cocked what remained of his ears. �Graciela was sure she heard sounds of struggle, muffled cries for help which seemed to be coming from the nearest of one of the many never-to-be-finished houses of Pueblo Nuevo.

Softly as a cloud in the soon to be silent night of her town, Graciela tip-toed a mountain of flesh nearer the unlit, half-risen walls of brick, raised herself as far as possible, which wasn�t all that far.�

And peeked.

*

Beneath her, upon a yet to be tiled yet ancient floor of poured concrete, lay the figure of a man bound hand and foot, his sacked head taped upon his body at an impossible and certainly very uncomfortable, angle.� A human figure which might be that of any of the unnamed thousands of victims of the narcos who hoped to hear society crash around them, a setting in which they had reason to believe they were more likely to flourish than the others.

Graciela looked around her.� She looked at her chained mutt who looked up at her.� She peeked once more at time�s prisoner and ventured a whisper.

Are you alive?

I am.

Who did this to you?

I don�t know.

Can you breathe?

Barely.

Can you move?

No, I cannot.

The trapped figure seemed to achieve a sudden flash of knowledge.

Governor, is that you?

It is.� Judge?

None other.� I was on my way to your party.� I�

My God, what has this world come to?� Wait.

I intend to.

I�ll have you out of there in a second.

I�d look out for myself if I were you.� They�re coming back.� They�ve gone to another locale the better to conceal a phone call.

A demand?

I presume.

For ransom?

I have inferred as much.

La gobernadora (for Graciela had been forgotten in the excitement) knew that in cases like this bodily evidence of secuestro was sometimes forwarded by one of the delivery services along with an inordinate demand for cash.� And yet, she hesitated to ask�

Have you got�your ears�your digits�your extremities..?

I have everything.� Except a breath of cool night air.� This hood is hot.

Perhaps el magistrado was about to say more.� Perhaps he had some thoughts upon Mexico as a failed state.� Perhaps he had some words for the archbishop of Guadalajara who might at this moment be blowing bubbles in his private pool.� La gobernadora would never know, for she sensed rather than saw a shiny black SUV, the type favored by narcos, gliding to a stop behind her.

Sensibly, she started for the back wall that walled every house in Pueblo Nuevo, even the never to be finished ones, from petty thieves.� Impossibly, she heaved herself over it, resting ever so briefly upon a jumbled heap of whole and broken bricks.� And, impossibly it would seem, practically in the same moment, chain dropped and trailing, el perro followed.�

They were over.� Out of sight.� And they huddled, woman and beast, listening to the night.� A softly slammed car door.� Another.� Footsteps.� A chaos of muffled sounds as the prepackaged magistrate was shouldered or dragged to the waiting vehicle.� It was time, la gobernadora knew, to leap the other way over the wall she had nearly tumbled over to save her skin.�

Yes, the time had come, the time was now, to confront evil, to challenge wrongdoers in the name of civility, perhaps even of civilization, but la gobernadora made herself as small as humanly possible. �As silent.� Nearly breathless.� El perro, crouched alongside, ears flat in the realization of the importance of keeping a low profile and head sunk into his shoulders.

A moment and it was over.� Her friend, el magistrado, had not broken, had not revealingly cried Graciela, if you will forgive the familiar form of address at a moment like this, save me!� At least call la polic�a!�

A sudden silence told la gobernadora the SUV was gone.� El magistrado had kept what dignity remained to him.� The night was the familiar night of Pueblo Nuevo, full of the peace which, given the current state of her country, indeed passed understanding.� The moon over Pueblo Nuevo rose unseeing or at least unoffended. �The stars she knew so well had not cried out or even commented.

In fact the stars witnessed a very large woman, Graciela by name, for Graciela was herself again, and a horribly disfigured dog, making their way down another street.� Stars Graciela had been born under, for they had not changed their courses very much in her handful of years.� Once more Graciela was walking thoughtfully through time.� And by now should be approaching her squeezed and nearly windowless house, when suddenly�

Close behind, she hears the muffled clippety-clop of an unshod horse.� Amazing how the sound of one horse might fill the space between the buildings, and carry with it the curse, the loneliness of the past when there was no paved road to Pueblo Nuevo but only, according to the season, a track of mud or dust.

Graciela leapt aside, atop the curb and well-secreted, at least as well as her bulk could be, behind a light pole.� Peeking out, she was surprised when no horse passed, in particular the unshod horse who with such urgency and imperiousness had claimed the darkness for itself as well as for times past.� Where can the animal have turned off in a street which brick and adobe houses line cheek to cheek?� Her mongrel too, unless he was only imitating her, had heard and foreseen the possibility of being tumbled beneath the hooves of time.�

In fact, she found the street empty and had only to step down into it and return to her homeward trek to restore what self-respect she might have lost in such a graceless, self-preserving sideways leap.

La gobernadora�

A small voice behind her stopped her, and her mongrel, in their tracks.

What have you done?

Very little, mumbled la gobernadora to herself, perhaps less than I ought to have. �And she turned to face the eleven year old form of one of her sister�s daughter�s sons.

What have you done to this creature? demanded the boy.

Seeing that he was referring to the chained beast at her side, she ventured I found him like this�or he found me.

I do not believe you, t�a.� This looks like your handiwork.

How would you know, you little brat?� Why aren�t you home in bed?

I was, said the boy.� I had a dream.

We all have dreams.

Not like mine. �I dreamt you and this dog had left this life far, far behind�

Would that I could, said la gobernadora.� Now why don�t you go home?� What�s your name anyway?� Just which of my grandnephews are you?

Carlito.� I dreamt you and el perro here were on your way to hell.

Thank you very much.

Only I knew even then in my dream you would never get there.� Therefore you were, and for generations may be, in el purga�

Yes, yes, Carlito.� Shut up, can�t you?� I remember now.� You�re the one that wants to be a priest.

Am I?

Come on, boy.� Shut your mouth and walk me home.�

A party of three--one extremely large, one small even for its age and one dragging a sturdy length of chain--now traversed brick and cobblestone, ploughed through timeless puddles of dust.� Though she should have arrived at her squeezed house by now, it occurred to la gobernadora that there might be time to waste a few well considered words on the lad.

Come now, Carlito.� No one wants to be a priest these days.� Nothing but words.� Repeticiones.� No women, none at all, even in mid-week.� Overcoming your loneliness, as well as it can be from the pulpit, drawing out the homily as the masses beneath you squirm...� How can you even consider the church?� The church which in a world riddled by bullets has identified certain forms of love as the evils of our time?� Can�t you think of something better to do with your life?� How did you ever come up with this notion anyway?� Thank God there are no priests in your family.� Come now.� Tell us the truth.

The boy hesitated, then began, I cannot think of another way to stop the animals of our earth from being worked to death or eaten.

Is that it?� Well, the yearly blessing of the animals has never done much for the animals of Pueblo Nuevo.� They are still overworked.� They are still eaten.� Listen, I haven�t met many priests who did not eat meat, except on Friday when they ate fish who are also God�s creatures.�

Suddenly it came to la gobernadora that these were the post party hours, the wee hours of the morning.

Carlito!� What are you doing out at this hour of the night?� Stop!� She stopped him.� Hear?� He heard.� That is the party I left, what�s left of it.� Without me.� Why are you here in the middle of the night talking to me?

I told you.� I�

What nonsense!� I don�t believe you had a dream like that.� You made it up.

At that moment the clatter of a half dozen horses was heard behind them.

Christ Almighty! cried la gobernadora and leapt for the curb.� Carlito was not far behind. �El perro had got there first.� The half dozen clattered by, iron shod, unsaddled, hurrying like mares to their stallion.� The silence did not seem eager to return but when it did the lady was quick to inquire�

Has someone turned the horses of Pueblo Nuevo loose?�

I think I recognized one or two, said Carlito, yet they hardly know each other, they do not belong together.

El perro had nothing to add and three stepped back into the street.

Underfed, said Carlito.� You could see their ribs.� They were foaming at the mouths for lack of water.� It should be a crime.

There is a movement to make it so.� The magistrate could tell you, if he hadn�t been kidnapped.� Yes, in D.F. a number of women have appeared before la camera de diputados�

Women do not really love animals, said Carlito.� They think they do but it is gratitude, or appreciation, they love.� The animals love them, however unreasonably, and the women believe it is because they themselves�

Now I know you�re nuts, Carlito.� Go home, slip out of your cassock, go to bed, shut your eyes and keep your condenado dreams to yourself.

I will if you tell me why you have spray painted this poor animal.

I told you, grandnephew.� I didn�t do it.

Here the boy bent low over the animal.� La gobernadora tightened her hold on the chain in case the unknown quantity, the grab bag of mongrelism, bit the little bastard in the face but the dog was gazing at him, as ever, with a look of rapt good will, perhaps even faith, and Carlito, deep in the graffiti, was in an ecstasy of discovery.

But look!� Here is your house!� And here!� Here is you!

Are you suggesting that that floating mine with stiff little arms and legs is me?

That is not my suggestion since you yourself did the artwork.� But here, here I am, at your side.

La gobernadora exhaled in order to bend as low as the boy and, sure enough, the floating mine did have a stick child at her side, obviously male, since there was a little extra stick sprayed in.

That is the child you will never have, t�a, said Carlito.� I am that child.

�Cabr�n!� Presumptuous, rash nephew.� Grandnephew.� Just which of my sisters� daughters� was unlucky enough to..?

My mother�s name is Luz.

Ah, Luz.� Just like her.� Does she know what a curse it was the day she gave the light to you or you to the light?

Carlito was about to answer, probably in the affirmative, when the cur once more was first to leap to the curb, and with such determination that la gobernadora was yanked after.� Carlito kept his probably affirmative reply to himself and leapt after them for no one was in a position to deny the horses were coming back.

The sound of thundering hooves preceding their appearance sounded very much like the end of time for the original half dozen had been joined by another half dozen at the least.

My God! cried la gobernadora.

Yes.� My God, said Carlito.� Can�t you see, t�a?� These are the unfed, the unwatered and the whipped!� As you remarked, the blessing of God�s creatures has been ineffective as always.� The mistreated animals of Pueblo Nuevo have been called.� Who knows who might be next?

Here aunt and grandnephew looked to the mongrel, who returned, as always, a look of absolute confidence in the decision making ability of his attendant humans.� Who knows what he saw in their eyes for, suddenly, freeing himself chain and all, the dog was off, desordenadamente, hightailing it for points unknown.

La gobernadora, who well knew she had no rights in the matter, was after him, propelling her bulk at an impressive, if unfamiliar speed.� For a while she heard or thought she heard little Carlito pattering after, but when she turned the corner she found, not only the dog gone, vanished like the once arrogant young men, components of competing cartels, hundreds of them seventeen and younger, tortured, disappeared, and, when she shoved her great head back around the corner, she found Carlito gone too, back between his black sheets, she supposed, dreaming in Latin.

And the horses must have chosen some side street for they had never appeared, were as gone as dog and child.

Graciela, for the governor had been returned, however briefly, by this double desertion to her essential loneliness, a loneliness in which she was sometimes a powerless, even a wordless, thirteen, pulled her great head back to look in front of her and the streets of Pueblo Nuevo were suddenly, painfully, unfamiliar.�

No, this was impossible.�

Streets she had known all her life.� Unrecognizable.� And there, in front of her, practically at her feet and, in this, the dry season, a rivulet, a kind of river right there at the all-too-familiar intersection of Joaqu�n �el chapo� Guzm�n and Ra�l Salinas, a river not of pure mountain water, a river altogether different.

A river of plastic.�

Bottles and bags.� Slow-moving. �Making all the unpleasant sounds of which plastic is capable.� Dumbfounded, la gobernadora (for the sight of overwhelming pollution had returned her to her unofficial official position) stood and gawked.� And the unnamed river deepened before her eyes.� It was a flood, a mighty R�o where only runoff had ever run before, a trickle of human history, a footnote, postscript to Pueblo Nuevo.

La gobernadora stood and stared.

Garbage added itself to the plastic.� An almost familiar stink rose.� And it got worse.

There, face down in the flow, already passing, a body, a human body, recognizably that of an adult male, a young man, one, no doubt, of the wasted or, as they said, the disappeared.� Dutifully, la gobernadora considered wading in, retrieving, identifying the body a mother would be grateful to bury, when she spotted another.� Another stiff, tumbling carcass, machine-gunned like the first.� And another.

La gobernadora, still on its banks, confronted a river of death.�

Not just the deaths of young men of whom it might almost be said disappearance was one of the norms of the age, but the deaths of animals too, for there were birds slimed, greased with waste, lifeless horses, perhaps the very mistreated ones Carlito was quick to point out before he too disappeared.� The rising, sinking bodies of cows, bulls followed.� And, back to the species we hold dear, dead children, smiling pictures of which no doubt adorned the hearths they�d left behind.

No, la gobernadora had not and would never have children and suddenly her greatest fear was that she would soon see Carlito float by, his black robes trailing behind him, his dead eyes fixed on an even deader sky.� And at his side, the mongrel, not even dog paddling but, downed by his chain, as dead as everybody else.

What has become of Mexico? asked la gobernadora.�

Could she have prevented this?� What should she have done differently when in proud possession of her particle of power?� And now: was she wrong to have quit the one profession she had ever known: la pol�tica?� Was she right to leave it all to the business party that was already using the police to replace the Cananea copper miners with those who had no choice but to work in unsafe mines and, on the same day, rounding up the widows outside the Pasta de Conchos coal mine in Coahuila, widows who only wanted their husbands� bodies, leaving those miners already interred where they lay?�

Graciela put her hand to her side.� Was that where her pancreas was, her liver, perhaps a distressed, or despairing, ovary.� Something, somewhere, in there, was amiss.� That was certain.

On the banks of a new, or very old, river, Graciela hung her head and the moment she did she heard�

�the toot-toot bang-bang banda of Pueblo Nuevo, tooting in the middle distance,� banging to bring back the dead�

No, she told herself, that could not have been tequila that flowed so freely at the reuni�n of single sisters, perhaps it was licor de ca�a, 100%, for somehow night has passed.

Son las cinco de la ma�ana�

�and, as might be said of almost any day in Pueblo Nuevo, it is somebody�s birthday.� Somebody is being born.� Not to la gobernadora perhaps. �But a generation of newborns, downhearted, dripping, is lining up for a premature, or overdue, dip in the river of death.� Yes, it is five, five in the morning.� Graciela knows what time it is.� She also knows the year.

It is the year in which we realize that things are as they will always be; nothing is ever going to change.� Those who have left Pueblo Nuevo are never coming back, those who have stayed are never going to leave.� El magistrado�� It is better not to think of him.� He had been, very nearly, a friend.� Graciela remembered him as a boy who played fair.� Now the adult was being tormented--for what no one would ever know--and, being the man he was, Graciela was sure, he was preserving a scrap of human dignity until the end.

La� gobernadora placed one not-so-dainty foot in a river that could not refuse her and another.� Graciela (at this moment, both her public and her private selves) was up to her knees in a surprisingly cold current when a veritable flood of familiar figures tumbled past and, though she could hardly claim to know everyone in Pueblo Nuevo, she knew some on sight.

There was Ana Laura who everyone had thought would stand before her class in la prepa forever.� And Anan�, encantada de la medicina, songbird in a family of songbirds who, when it was time to go, had still found time to sing to her patients on the night shift.� And Jorge, in his box, still writing his dearest Mar�a although his whereabouts, until this moment of course, had remained unknown.� And Alondra, the generous, Alondra, the evenhanded, Alondra of the sliding scale at ease upon her back in the blackest of black rivers.� Not to mention Hernando, el contador, who would count trees till there were none to count.

Graciela!� Querida amiga, is that you?

A spinning Hernando, caught in an eddy, had wiped his mouth and hollered. She and he had been students together at la prepa and la gobernadora could hardly ignore such a warmhearted salutation, such undying affection.

It is I, Hernando?� Where are you off to?

Never mind that.� How I got here, that�s the story. �I was piloting my hang glider on one of my favorite flight plans.� There�s this nice little number, you see, who has a pool smack dab where the forest used to be.� She swims afternoons without a stitch�� To make a long story short, I must have pulled something I shouldn�t have and the next thing I knew I�

Hernando was gone but along floated Rosa, deft handler of knives, shaper of the shapeliest bouquet of all, Rosa, whose eyes would not stay open on the job.� And Candelario, the slipped, the fallen, Candelario, who would have been one of the men of Mexico, Candelario, who always knew he had to do something, just never knew what.� And Aurora, his teacher, la profesora for whom history was, finally, if a little late, hilarious.� Not to mention �ngel of the charmed life, dancing in double time, roses in both hands. �And Rafael who paved--as well as possible--the three blocks of Benito Ju�rez, and Xochitl, his beloved, whose life, until now of course, remained a mystery.� And Paloma, white as a white bird, her chair gone to the bottom, la gobernadora supposed, in silence issuing a soundless sound, a lament only crowds and circus animals could hear.

And thin-lipped Alba, if a little late predicting rain, her little sister, Rosalba of the perfect breasts and, of course, Juan Carlos, the map of Mexico firmly in his hand.� Alba, the big sister, the lifeguard, had Juan Carlos in her grasp, towing him to a place where he might safely watch the world go by�

And Auriliano who did not die face down between the rows, his son who could do nothing right and his father, still staring at the man of mud.

But there!� Isn�t that Alondra, the openhanded, the giving, coming round again?� Whoever heard of a circular river?� Well, maybe in Mexico, determined la gobernadora.

Alondra! �Go home.� Your boyfriend is looking for you.� Uriel.� One of three.� He even asks al tribunal to see if el magistrado has sent you up for something or other.

I know, bubbles Alondra.�� I�ve seen him, I�ve heard him.� He has a good heart.� One day I�

But Alondra�s kind words are lost in a kind of brokenhearted swallow, a gulp la gobernadora cannot forget, for it was Alondra, yes, Alondra who not only pumped her umbrella--up, down; up, down--her umbrella dark as the marigolds of death, but Alondra who wanted to work in her campaign, who believed, for reasons known only to her, that la gobernadora would build a better world.�

But oh..! �Alondra has slipped beneath the surface.� La gobernadora feels something wrench inside of her and for this girl alone, for Alondra, cries after�

Alondra! ��Hija! �My child! �You too would build a better world.� I know.

Strangely, silently, the torrent is gone, the corner of Joaqu�n �Shorty� Guzm�n and Ra�l Salinas is its sordid, sleazy self.� The river of death has been a flash flood merely, un torrente, not unknown in these parts, and la gobernadora, high and dry except for her big feet, and having, for the moment, forgotten her friend, el magistrado, is thanking her lucky stars for, as so many in this, her Mexico, know, a hairy getaway is better than none at all, but no..!

Graciela, still on the slippery slope, has slipped, she is down, she is on her knees, on all fours as no governor should ever be, grasping the fact she has a handful, two handfuls of, muck, when�

Suddenly. �Once more. �The sound is upon her.� It is, she knows instinctively, the rumble, the roar of los caballos, the scream, el grito, of the underfed, the mishandled and the harmed��

At first, the sound and only the sound, yet, la gobernadora knows it in her bones as in her still warm, perhaps excessive flesh: the gallop has assumed an element of fright, if not terror; it is, in fact, a horrified headlong run...

Una estampida.

The horses are charging Joaqu�n Guzm�n, skidding, spewing sparks, tripping, stumbling white-eyed, taking the corner onto Ra�l Salinas�

Graciela watched them come.

Michael McGuire was born and raised; he divides his time; his horse is nondescript, his dog is dead.� McGuire is rumored to have bent an elbow once or twice in D.F. with B. Traven; but the facts in this case, as with so many in the writer�s journey, are uncertain.

"McGuire's writing is hauntingly thoughtful, inexorably true."

--Publisher's Weekly

A book of his stories (The Ice Forest, Marlboro Press, distributed by Northwestern University Press) was named one of the �Best Books of the Year� by Publisher�s Weekly. McGuire�s stories have appeared in The Kenyon Review, The Paris Review (x2), Hudson Review, New Directions in Prose & Poetry (x2), etc. His plays have been produced by the New York Shakespeare Festival, the Mark Taper Forum of Los Angeles, and many other theatres here and abroad, and are published by Broadway Play Publishing. One, La frontera, set in the same world as the stories, won the $10,000. International Prism Competition. The Scott Fitzgerald Play, University of Missouri Press, a Breakthrough Book chosen by Joy Williams, has been published as an Author�s Guild Backinprint edition. Both books are available on Kindle.

Home