Home

Editor's Page

Was Jesus God?

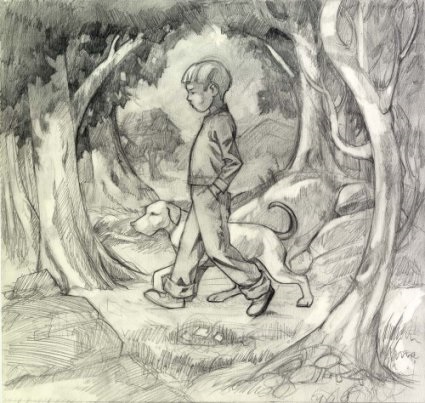

A while ago I published a piece here in SouthernCrossReview called We are the Lucky Ones, (by “Z”. It described an essay, or the manuscript of one, that had been found by my son and his dog in an old lunch-pail in the wooded part of our property here in the valley of Traslasierra in the Province of Córdoba. I didn't expect that something else would ever be found here, that finding the lunch-pail was no more than a unique stroke of luck. But fate is fond of playing tricks.

Just last week my son and his dog were investigating the flora and fauna (insects) in a dry riverbed at the far end of the wood, actually outside of our property because the riverbed acts as the natural border, no-man's-land so to speak. There, thanks to the dog's olfactory talent, they found an old rucksack caught under some fallen branches. It looked as if it had floated downstream, carried by the current until it was snagged by the branches. The problem with that theory is that, according to the neighbors, there hasn't been water in that stream for at least twenty years. It's possible, though, that the rucksack had been stuck there for over twenty years, for it was sturdy and almost hermetically closed, as a German label indicated it should be.

What the dog smelled were the rotten remains of a sandwich wrapped in wax Paper, and a blue notebook, also of German quality. In it someone had written an essay, or at least some thoughts on a subject which obviously interested him greatly. It interests me as well, so I have translated – from Spanish – and copied it here.

“When I was little I had to go to mass every Sunday and on so-called Holy Days of Obligation, and receive Communion at least once a month. That wasn't so bad. But in order to receive Communion you must be free of sin, which in turn means going to Confession in order to free yourself from sinfulness. That part I didn't like, not at all. First of all I feared that the priest would recognize me despite the confessional being dark. I couldn't see much of him, but I knew who he was because his name was over the entrance of the confessional. I could smell him as well, especially his bad breath. I didn't have much to confess, just stuff like I didn't say my prayers and I disobeyed my mother. He kept his eyes shut so from his profile he looked like he could have been sleeping. I can't say I blamed him, because my confession was pretty boring until near the end, like an afterthought, I mentioned dirty thoughts.

He woke up then, probably his dick did too. "What kind of dirty thoughts?”

“About girls, I guess.”

“Um-hum, and did you masturbate?”

Of course I masturbated, you dumb schmuck. How else am I gonna have dirty thoughts? But I said, “Sometimes.”

“How often have you masturbated since your last confession?” like he needed details for his report to St. Peter. I mumbled something, some number which I won't reveal here because you probably wouldn't believe me. He did though: “Wow!”

It was really embarrassing, but I believed that I had to go through the demeaning torture of Confession and answer the priest's cruddy questions because I had been brainwashed to believe that if I died with a sin like jerking off on my soul, which is apparently worse than murder, I'd be condemned to eternal damnation in hell. That's their not-so-secret weapon: fear!

Finally I began going to Confession less frequently, then not at all, which meant that I couldn't receive Communion (unless I dared go to the altar rail anyway, which I didn't because that's probably an even worse sin than I could imagine). I told myself, however, that someday I'd go to a slam dunk confession and be right back in the fold – but I never did. Although it wasn't the final nail in my Catholic coffin, what I relate now was one of them and it helped.

I was about fourteen, fifteen and I tended to neglect going to Sunday mass. My parents were only nominal Catholics, young, who went out till late most Saturday nights dancing and drinking in a local pub. They didn't care if I went to church or not. Only my father's sister, Aunt Gert, dragged me along sometimes. But I had this friend, Ken, a few years older than me, who was an ardent Catholic. When he noticed that I was skipping mass he decided to save my soul and asked me to go with him because it was really very important. I liked the guy and didn't want to wind up in hell anyway, so I went along with him the next Sunday.

It was pretty boring as usual, but something important – for me at least – happened as we were leaving. A couple of smiling usher types – the same ones who passed the donation plate – handed out a pamphlet to everyone leaving. It was the infamous “index” The Index Librorum Prohibitorum, a list of books forbidden to Catholics. On it was the book I'd just finished reading and had become my favorite: The Three Musketeers, by Alexander Dumas. Along with it were most of the interesting and important books ever written. I finally figured out why The Three Musketeers was included: one of the bad guys was none other than Cardinal Richelieu. That didn't separate me completely from the Church, yet; the guilt feeling was still too great.

But that's all background. The final break came when I began to read the Bible, and analyze it. Previously, until Martin Luther, the Bible was only available in Latin, thereby automatically making it inaccessible to everyone but the priests. So they could tell the masses – us – whatever they wanted, true or not. Not any more. It took me quite a while to wade through the Old Testament and finally enter the realm of the New, which is what really interested me. The priests told us that Jesus was God and he gave them, and only them, the “keys of the kingdom” meaning heaven, with which they could let us in or keep us out, the only other place to go being hell. They would let us in with their keys only if we were without sin, and the only way to be without sin is to confess to them what they call sin and beg them – not God – to forgive us, i.e., make us sin-free. Man, that's power!

I read through the first three Gospels and didn't find anywhere that Jesus says he's God. The Son of God? Well, yes, but we're all sons [and daughters] of God. He talks a lot about his Father, which I presume means God. So how can he be his father and himself at the same time? Then comes the cruncher. The beginning of the Gospel of John reads: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God...And the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, as the Father's only son...” Have you ever read anything so ridiculous, so obviously wrong? How could the Word, who became flesh and lived among us [as Jesus] be with God and be God at the same time? He could not. So it's all a lie. Jesus was not God! Don't get me wrong. I love Jesus of Nazareth, he was truly a great guy and someone special, but not God. That was the last straw, the last link to the Church. I was free. Except … I still don't know who or what Jesus really was.”

Like Z's paper it was unsigned. I don't think it was also by Z because the style is different, but I gave it that name anyway, if only because it was found in the same general vicinity. Here Z's logic seems indisputable. The Church fathers were not in agreement about whether Jesus was God or not, so it seems they came to a most unsatisfactory conclusion that Jesus was in fact God, but also the Son and to top it all off as the icing, the Holy Spirit. To further enhance Z's thesis, there's a new translation of the New Testament by David Bentley Hart in which he promises a literal translation from the Greek. When he bumps into the confusing prologue of the John Gospel, he feels he must do something, even if what he finally does confuses the issue even more. I must explain here that neither ancient nor modern Greek has indefinite articles. I don't know Greek, but I did once study Russian, and learned that that cyrillic language also abhors such articles. Therefore in Russian the words “In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God.” would look like this: “In beginning was Word, and Word was with God and Word was God.” Whether the meaning is: and the Word was a god, or God, can only be determined by the context. The same is true in Greek. (I checked.) Therefore, because the context “was with God and was God” is impossible, the correct translation must be “In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God (ho theos) and the Word was a god. (theos)”

Hart tries to do justice to the Greek by translating ho theos as GOD (one large capital followed by two small capital letters) and theos as god in small letters, thereby avoiding the indefinite article “a”, apparently because it might be understood as his interpretation. Therefore, his translation reads: “In the beginning there was the Logos, and the Logos was present with GOD, and the Logos was god. This one was present with GOD in the origin. “ This seems to confirms Z's contention that the New Testament does not describe Jesus as God himself, but only a god, in the sense of a divine being, such as angels, archangels, etc.

In Z's lunch-pail dissertation he mentions Rudolf Steiner and Anthroposophy. There we also find Steiner's firm contention that Jesus of Nazareth was not God the Father – how could he be when he often refers to “my father” or “our father”, but rather a godly being sent by God the Father to incarnate in Jesus of Nazareth at the baptism in the River Jordan. Z, whoever he is or was, figured it out by himself without deferring to experts of any stripe, for which I would gladly congratulate him if I could.

Frank Thomas Smith, April 2018