Home

Part 10

It was almost evening.

The ram-horns were already being blown. Announcements that the feast was about to begin. I could hear the death cries of the slaughtered animals from the temple mount, the city already smelled of fresh blood which flowed from the altar down through the gutters to Kidron and the stink of the entrails which had been burnt on the altar lay repulsively in the alleys. The first celebrant passed by holding his lamb in his arms, disemboweled, bled to death. That vile temple slaughtering. Thousands of lambs died that day. Death, everywhere blood and death. How could I eat a lamb that evening? How could I ever again eat the flesh of killed animals? Each animal’s death cry is his, all the blood is his. But then how should I go to the Seder feast without eating lamb? It was the law: the lamb must be eaten, eaten up till the last morsel. In remembrance of that last meal, which our forefathers ate before the removal from Egypt, standing, ready for travel, hurried. And nothing of the meal may be left over. Since then it has been duty, commandment, strict law: every Yisraelite must participate in the Seder feast and must eat of everything on the table. Also the lamb, the usual food. I cannot. But one must. It is a sin not to eat the Seder meal. But why a sin? Didn’t the rabbi say that it isn’t what goes into the mouth that makes one guilty, but what comes out as evil words? Can I rethink the law? Fulfill the law by freeing myself from it? There is only one commandment, the rabbi said.

My decision was: I will go later to the supper, after the lamb has been eaten and the bones cleared away.

The sun had gone down red under the smoke from the fires, and the moon rose high, almost full, and I still ran through the alleys like one who had no family and hadn’t been invited to the Seder meal.

People spoke to me twice, taking me for homeless or poor and wanting to take me home with them, as is every Jew’s duty. But also: two men spoke to me: you, a Jewess, aren’t at the meal? Or aren’t you a Jewess? Anyway, you’re pretty, come, we’ll pay you well.

They grabbed me, I broke free, they chased me, I fought with hands and feet, they fought too, and ripped off my cloak. Then I got away from them. My cloak lay on the ground. I remembered something: “The guards found me on their rounds through the city, the wall guards took away my cloak”. The night was cold. I froze. I ran to Veronica’s to ask for a wrap of some kind.

Are you crazy to run around tonight? And how you look! Come in, we’re just stating the Hallel.

I can’t, let me go.

She gave me a shawl of white wool, nice and warm, but white. We didn’t realize that the whiteness acted as a signal in the moonlit night. And we couldn’t guess what a puzzle that white shawl would pose for those who were with us later on the Mount of Olives. A white form of light, an angel with a chalice full of consolation. Too much.

But that hadn’t happened yet. I sought out a dark corner from where I could see the door of the house in which our people would have the Seder meal. I heard footsteps. I recognized his among them all. Before he entered he turned and looked in my direction. I held my breath until the door had closed behind him and the others. I stood there and stared at the window behind which there was light, and I heard the songs and the blessings and knew what was happening: now the host blesses the first cup, now they wash their hands, now they dip the herbs in the salty water and eat them, now the host blesses the matzo and puts a piece aside, now the host begins to read the story of the departure from Egypt, now they sing the Hallel…

I didn’t hear the words. I looked up at the moon which, waning, hung gloomily over the temple mount, and then I saw a cat slinking over a wall toward a crevice in which a dove sat. Such bitter anger overcame me that I threw a stone at it and yelled: Thou shalt not kill!

I didn’t hit it, it sprang over the wall, the dove fluttered off. Murder, murder everywhere. I gnashed my teeth, like Yehuda.

Yehuda: now he is at the table, now he drinks some wine, now he eats a piece of matzo, now he dips the bitter herb in the stewed fruit, now he eats the bitter herb between two pieces of Matzo, now he drinks from the second cup. And always together with Yeshua, always under Yeshua’s gaze. How can he stand it? Now they bring the roasted lamb. That they can eat on this night! Doesn’t it stick in anyone’s throat? Doesn’t anyone choke on a bone?

That smell of roasted flesh. I feel sick. So many lambs killed. Murder, murder. I return to my corner. They are finished eating. They sing the final prayer. Now they drink from the third cup…

The door opens and someone comes out, ducks into the shadow of the wall, stays there a moment, then runs away as though being chased. Where is he going? What remains for him to do?

In the room they began to sing the third part of the Hallel. Time for me. I knocked the agreed signal on the door, someone let me in, I went up the stone stairs, entered the room and looked for my place at the table. Yeshua pointed to it: at the end of the table. His mother sat at the other end. The place opposite him remained unoccupied. It remained unoccupied forever.

No one asked me why I had come so late. Afterwards Yochanan told me that the rabbi said when I was still missing: Let’s start, she’ll come at the right time.

The meal was over. Yeshua stood and accompanied the guests to the door. He gave us a sign to stay. We sat down again. What would come now? Yeshua had a bowl brought in, a pitcher of water and a large linen cloth. What for, we had already washed our hands.

It wasn’t hands that were to be washed. Yeshua placed the bowl and pitcher on the floor, girded his robe high and kneeled before those who sat on his right and left: Shimon. He jumped up: ”Rabbi, what are you doing? Stand up, I beg you!

Sit down, Shimon, so that I can wash your feet.

Rabbi, no, never. You, of whom the great Baptist said: I am not worthy to tie his sandals!

Yochanan said softly: The heathen Romans do that during their Saturnalia. Masters and servants exchange roles.

Yeshua heard him: Yes, but the exchange is a joke and is only valid for a few days. For us, however, it is a sign of the new testament between the Godhead and humanity, and therefore between man and man. In my realm there are neither servants nor masters, neither rich nor poor, neither powerful nor powerless. In my realm each is the servant of the other. My realm stands on these words, as does peace on this earth. Therefore sit down, Shimon!

While he was washing and drying the feet of one after the other, he said: When I leave you, and it will be soon, I leave in order to come back. If I did not leave, I could not return.

Shimon cried: Take us with you, Rabbi! Wherever you go I want to follow. I want to give my life for you.

Yeshua said: Friend Shimon, this night you will deny that you know me. Before the cock crows and morning dawns, you will have denied me.

Rabbi, what are you saying! That will never happen.

It will, Shimon. But what you say will also happen: you will lose your life for me.

When, Rabbi, when?

I saw Yeshua smile, for the way Shimon said it didn’t sound like he was very anxious to die for the rabbi.

Yeshua said: When I have left you, I will send the spirit of knowledge to you, and with the knowledge of truth also the strength to die for it. Not all of you will die a violent death, but none of you will be spared from death. I’m not speaking of the death which everyone dies at the end of their years on earth. I speak of the death which precedes rebirth in the spirit.

Someone asked: Rabbi, how can one die and be reborn before the end of his years on earth?

Yeshua said: Whoever does not sacrifice himself to something greater than his I will never be reborn. Whoever holds fast to his I will lose it, whoever sacrifices it, will have it. Only he who burns up his I in the fire of love will enter into my realm and find me there again, and there will be no more separation.

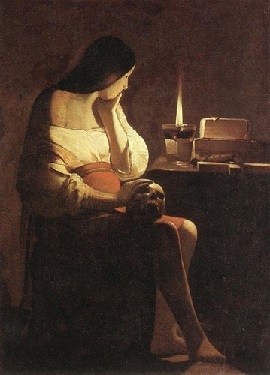

When he came to me he said: Miryam, you washed my feet with your tears. Now it is my turn to render you this service.

Then he looked up and said: Smile, Maccabee woman! Victory is surely ours. But count no longer in years and decades. Count in aeons, as I do.

Then he walked around the table and came to his mother, but he didn’t wash her feet. He said: You need no washing, you are pure from the beginning and the grand handmaiden.

And he embraced her.

Then he had the bowl, jug and cloths taken away and sat again in his place. The Seder feast had ended long ago. We heard footsteps and talking and laughter from the alleyways. The people who had been guests at various places were on their way home, full and cheerful, for Passover was a joyful celebration: the remembrance that our forefathers had been freed from Egyptian captivity by Moshe and the waters of the sea plunged down over the Egyptian soldiers and Miryam and her women sang and danced.

Yeshua waited until it was quiet outside. Then he called for a fresh matzo and a large cup of wine. He then broke the matzo into small pieces and said: This is how I will be broken, this is how everything living will be broken, for everything still stands under the law of death.

Then he dipped a piece of Matzo in the wine, and said: And this is how all will be reunited when I steep the earth with my blood. From then on the law of death will no longer be valid, but rather eternal life in the spirit.

He ate the first piece which was dipped in wine. Then he stood up, went from one to the other, handed each a piece of matzo and had them drink a sip of wine.

Four cups of wine belong to the Seder feast. But this fifth one: did it belong as a sign of abundance? Or was it already the first cup of a new feast?

But there was no time to think, for something happened which was not attainable by thinking and which all of us experienced in a like manner; we confirmed it later: the room was no longer a room, it had extended into boundlessness, and with the room we were consumed by a silent white light. It seemed as if we had been sitting for an immeasurable time in nowhere. But as Yeshua began to speak I realized that I still had the piece of matzo in my mouth. No more time had elapsed than that between chewing and swallowing.

Yeshua said: What you ate and drank, I am, and I am the life which death knows not. As often as you repeat this meal, you eat and drink ME.

Then he stood and said to Yochanan: Take my mother home and come back quickly. It is time for me to go. Hear what I tell you: Do not be confused by all that you see during the next hours and days. It must happen. It is my will since eternity. I must leave in order to be able to return. Do you understand that? Will you think of it when you see me like a worm, kicked, beaten, spit upon and hanging on a cross? It is only Passover: transitory. Passage. Come now, I wish to spend this night, as much of it as remains for me, on the Mount of Olives.

He didn’t say: Come with me! As he usually did. But we all followed him. We went through the lower town and through the KIdron valley. We had to pass through a gate there. It was heavily guarded. Why did the watchmen let us through? Yochanan whispered something to them and they let us pass. Did he know the password? Who gave it to him? Nicodemus? Or did he have other important friends on the Council?

We came to the crossroads where Bethany was to the right and the olive grove, which belonged to the Gethsemane estate, to the left. My hope was that Yeshua would turn right, go to Bethany, sleep there in safety overnight and leave the area tomorrow, and everything would be all right. And then? What then? There was no then and no other. He had to turn left, he had to go to the grove, he had to follow his path to its end.

I went with him. I would have gone to death with him had he allowed it.

Shimon said: Rabbi, is it smart to stay here? The watchmen recognized you. They can betray you to the henchmen.

Shimon, another has already betrayed me.

Rabbi, whoever it is, I’ll find out and take care of him. He should only show himself! Here! This! And he touched the purse on his belt in which he carried a dagger.

Shimon, Shimon, get away from me. Your betrayal would be worse than that of he whom you want to stab.

Rabbi, I only mean it as love for you.

Shimon, don’t be presumptuous. There are many forms of love. Don’t talk like a child. I tell you: You shouldn’t kill even in thought.

But if someone attacks you, Rabbi…

Yeshua gave him no answer, for Shimon knew it.

We continued walking until Yeshua said: Stay here and be on guard.

Be sure that we are on guard tonight! We will take turns. Don’t worry!

He walked on. It was dark under the old olive trees. I sat in a position so I could watch Yeshua, but also the path that led up from the city.

I sat apart from the others. They wanted to stand guard? One after the other they sat down. For a while I heard them talking. From the tone they were reciting prayers.

Then it gradually became quiet. They had fallen asleep.

After a while I heard Yeshua’s steps and voice: You’re sleeping? Didn’t you want to stay awake with me? They jumped up like surprised children. Yeshua had hardly left when they fell asleep again, and again after a while Yeshua came and found them sleeping, and then a third time.

The third time Yeshua said: Sleep then, the night will be long.

Why didn’t he think of me? Shouldn’t he have known that I stood guard with him? Who else but she whom he called Maccabee woman?

I crept toward him until I was close. He must have heard my footsteps, and he certainly felt my nearness. But he didn’t turn around. Was I a bother to him at that moment? He could have sent me away. He didn’t. He tolerated the witness.

He was kneeling. As the moon wandered farther a little light fell on him through two tree tops. His face was wet with sweat. He looked like someone who had just left a boxing ring.

Rabbi! I’m here.

I know, Miryam.

Should I go?

Stay. Come closer.

Rabbi, how cold your hands are. Tonight mine are warm.

Miryam, when we next see each other I will be hanging on a cross and you will stand below and our eyes will meet for the last time. But the separation will be short. Have courage, my Maccabee woman. Your courage gives me strength.

Rabbi, take my strength! You are suffering beyond measure.

It is MY measure, Miryam. That’s why I have come to earth, in order to suffer all human suffering. Your suffering is also mine. All the wounds of this earth come to me. All despair falls on me. I must outweigh the measure of your suffering with mine. If only a small amount were missing, the scales would be out of balance. Go now, Miryam! This comfort is now also forbidden me.

No more embrace. He was already taken from me. But I was not able to leave him alone. I hid behind a tree. I also had to suffer my full measure. To see him suffering so was beyond measure.

Suddenly I saw lights between the olive trees. They moved in a column coming up the hill. Friend or foe?

Yeshua must have seen them. He stood up and approached them. The sleepers woke up. They gathered around Yeshua. They understood: these were the henchmen, the time had come.

He pushed the disciples aside and continued to approach the henchmen.

Who are you looking for?

Yeshua, the Galilean, the rabbi from Nazareth.

I am he.

What happened then? Why didn’t they grab him? Why did they step back? For a few moments it was as if a living picture had turned to stone. What had these rude soldiers heard?

I AM HE.

Nothing more. But this was THE WORD.

Then one of them shook off the immovability. Yehuda went up to Yeshua: Shalom, Rabbi!

And he kissed him.

Yeshua looked him full in the face. I was standing near. I saw Yeshua’s look: it was full of compassion and of something I must call respect. For an instant they stood next to each other like brothers, equal to equal, conditioned by destiny. I didn’t see Yehuda’s face, but I heard Yeshua say: Friend, what are you doing? He said it so softly that one could expect that such gentleness would disarm Yehuda. But it was just the gentleness that infuriated Yehuda. Had Yeshua defended himself, had he cried: “Rise up against the Romans” – Yehuda would have carried him on his shoulders and converted the henchmen into followers.

But that didn’t happen. Yeshua held his hands out to the henchmen as though in greeting.

The tied him with rope.

Shimon jumped forward in rage and drew his dagger.

No, not that! Yeshua cried.

But Shimon had already struck, blindly, and he hit a henchman on the ear. But then he was afraid and fled. Instead of him a henchman grabbed me, but he got only my white shawl, which remained in his hands. Then I fled.

We all fled, if not all the same distance. Today I think: What could we have done at that time? Run into the city, call the rebels together, give the signal for the uprising?

Yeshua’s disciples: cowards. Later they would be heroes, some dying grand deaths for their loyalty to Yeshua.

We followed the henchmen’s path at a safe distance. But the gate closed behind them. Punishment for our cowardice: banishment from participation in the great tragedy. But once again a word from Yochanan and the gate was opened for us. We were able to keep up with the henchmen.

Where did they bring Yeshua?

They turned in the Kidron valley at the lower town and went up the stairway to Hananya’s house. The path ended in the courtyard.

Why Hananya? He wasn’t the high priest that year, he was only the high priest Caiaphas’s father-in-law.

Hananya was not competent to preside over a trial, but perhaps it wasn’t to be a trial, perhaps that experienced old man had doubts about what was said about this Yeshua, good and bad, perhaps he was really interested, who knows.

What is the content of your teaching? In whose name do you act, in whose name do you heal the sick and drive out demons?

Yeshua said: I have taught in public, all could hear me, I have healed in public, all could see me. So why do you ask?

One of them struck him in the face: You are to answer when asked.

Yeshua spoke softly, but everyone in the courtyard could hear him: If I have spoken unjustly, prove it to me; but if I have spoken justly, why do you strike me?

I almost shouted: Does the Law allow one to be struck who hasn’t yet been declared guilty?

But I bit my hand and forced myself to be silent.

Obviously Hananya also thought that they were acting illegally, and he said sullenly: Take him away.

They did so. We followed him. Nobody stopped us. They made Yeshua wait, still fettered, in the courtyard of the house where Caiaphas had his office. They didn’t even allow him to sit. A fire burned in the center of the yard. I would have liked to warm myself, the night was cold, but I didn’t dare step into the light. Shimon did. A maid who was putting wood on the fire looked at him suspiciously: You’re one of the accused’s followers!

Me?

Yes you!

But I don’t know this man.

You betray yourself, you speak Galilean like him.

I swear that I don’t know him.

A cock crowed into the dawn.

“Before the cock crows, Shimon…”

Yeshua turned to Shimon – who ran away.

They let him go.

Poor Shimon. As long as he lived he deplored that moment. But on the other hand: What could he have done? What he wanted was to be near the rabbi as long as possible.

So only Yochanan and I remained, Yochanan with some secret permission, which also included me. Yeshua must have sensed that we were near. Once he turned his face in the direction where I sat. I whispered his name, but I doubt that he heard me. They made him wait.

The guards were bored. They blindfolded him, struck him and said: Prophet prophesy: Who hit you?

Children’s play.

I trembled with anger. If I jumped up and cried: Play that game with me, strike me, leave him alone!?

Ridiculous idea. Who would have struck me, a woman against whom there was no complaint? It would have caused laughter, nothing more.

With every blow I dug my fingernails deeper into my palms. At least that. Finally Yeshua was led away, still bound. This time Yochanan’s words had no effect, they held us back. I pressed a piece of gold into a policeman’s hand. He took it, but didn’t let us pass.

They brought Yeshua to Caiaphas, the high priest.

We found out what happened there from Nicodemus in the time between the hearings by Caiaphas and those by Pilatus. Yeshua really had a legal trial. They even had witnesses who testified individually. What did he say about the temple, its destruction and rebuilding? But the testimonies were contradictory. Finally the whole accusation broke down. The court had nothing concrete.

Commotion and confusion.

The only possibility was to make the accused confess.

But confess to what?

What do you say to the accusations brought against you?

Yeshua, who stood in front of the steps on which Caiaphas stood and was therefore lower than him, looked calmly up at the high priest like one who is stronger looks down upon a weakling and Caiaphas, according to Nicodemus, was conscious of it and it confused him, and the confusion grew when the accused remained silent.

You must answer!

Silence.

Answer!

Then Caiaphas went down the stairs, stood in front of Yeshua, grabbed his garment at the neck and cried: I tell you to swear by the Almighty to tell us: Are you the Messiah, the son of the Almighty?

It was, Nicodemus said, not a question for a criminal hearing, but the tremendous and desperate question of Yisrael, even no longer a question, but an oath with the highest and most holy formal oath known to Yisrael, and to which not to answer or to answer falsely would be considered blasphemy.

A terrible silence followed.

Then Yeshua, having been forced to answer, said, without raising his voice, simply, just as he might have answered a common question: You say it.

Now they had what they wanted: blasphemy. Caiaphas tore his garment, a confused tumult filled the court: the death penalty.

But Rabbi Nicodemus, I said, that’s not correct. He didn’t say: I am the Messiah and the son of the Almighty, he said: You said it. That means: You say that, not I. And furthermore: even if he presented himself as the Messiah, as some before him had done without being punished, you can’t simply add the second part of the sentence in the same breath: the son of the Almighty. They were two completely different charges. It doesn’t make sense.

Miryam, it makes no sense and it does. Whatever Yeshua may have answered, he would have been misunderstood because he had to be misunderstood, because it was so decided since eternity.

The judgment had been made: death. For that only Rome’s representative was competent: Pontius Pilatus.

It was morning, the city was awake. A pile of ants. We were pushed, shoved, stepped upon. The pilgrims for the feast were there, and many more had come, whole families, almost whole villages with donkeys and provisions for the whole week, and those who found no place to sleep in the city went back through the city walls to look outside for camping sites, tents, huts, caves. There was so much movement in and out that Yochanan and I had trouble keeping together.

Yochanan, these people have no idea of what’s happening today and that their fate is being decided at this very moment. Listen to how they laugh and joke. They all live. Look how they live. Everything may live: the doves, cats, lizards, donkeys, and things live in the earth and the grass lives and the worms in the earth. The sun shines on the whole swarm of life. But he must die, Yochanan. He will die! Yes, yes, I already know what you want to say. So keep quiet. What do you know of my love? Keep silent, above all no false words of consolation, no pious speeches or I’ll scream!

He looked at me, shocked. My hair had come undone, I must have looked like a rabid bitch.

So he said nothing. I knew what he was thinking: As if I, Yochanan, whom the rabbi loves, don’t also suffer! What do you know of my suffering?

We walked on together that way for a while, pushed, shoved, and both of us suffered from an overdose of sorrow and fear.

At a corner someone bumped into us, cursing loudly and terribly and tearing his clothes as he ran. A madman.

Yehuda.

He ran on, tripped, fell, got up again and lost himself in the crowd.

Finally we came to the large square in front of the Praetorium. What did all those people want here so early? And what people they were! Not pious pilgrims, they went to the temple. Also not honest merchants and feudal masters. Those faces, lean and hard and decided, were rebel faces.

I asked a man: What’s going on here?

Nothing’s going on, as you can see.

Another said: And we’re here because nothing’s going on.

I said: Should something be happening?

What are you blabbering about? This is no place for females.

I said softly: Your liberation decision, which is it: Yeshua of Nazareth or Bar Abba?

Who are you anyway?

Someone who knows the Rabbi Yeshua well.

Then you know a windbag.

How dare you say that about him!

Hoho, old girl. Watch your tongue and your eyes.

The other said: He’s finished, they’ll crucify him, that’s for sure.

Yochanan kicked me to shut up.

But I didn’t shut up.

What did Rabbi Yeshua ever do to you?

Made us hope, then left us flat.

Before I could answer Yochanan dragged me away.

We pushed forward and finally got right in front of the terrace on which Pontius Pilatus was to appear.

Like a bee swarm gradually stills its buzzing, it became quiet in the square, for a column of high priests, scribes and police came, and in the middle Yeshua, still bound. It became so quiet that one could hear the pigeons cooing. Then Pilatus came out of the building. That was surprising. Otherwise he acted behind closed doors. But because it was forbid for Jews to enter a courthouse before Passover, the Romans had to come out in order to satisfy them.

Pilatus sat.

Yeshua stood to the side of him. They looked at each other.

Then Pilatus gave the sign for the priests to state their complaint. One of them spoke:

This man, Yeshua Ben Josef of Nazareth in Galilee, rabbi, wandering preacher, is the cause of great unrest among our people. He claims to be the Messiah and the king of the Jews.

Pilatus knew the story. Caiaphas or some other member of the High Council had already informed him early that morning.

I found out what he thought of the case a few hours later from Veronica, who secretly had a relationship through a friend with Procula, Pilatus’s wife.

Pilatus was already in the picture before the visit of the High Council men. He wanted nothing to do with the case, which was so Jewish that he didn’t understand it.

What, by Jupiter and all the gods, had this Jew Yeshua done wrong? Incite the people? The people had been in a state of unrest for a hundred years, not since three years, since the appearance of this Galilean. Understandable that they were dissatisfied. Which occupied people was ever satisfied? Furthermore this Yeshua had never said anything against the Romans, at least not directly and before reliable witnesses. There were other, real rebels, and the Jews had never demanded their death. There was this Bar Abba, a rebel, a leader even, who was in jail, and no one from the High Council paid any attention to him. So what was so special about this one?

I can find no guilt.

Much shouting: He claimed to be the Messiah!

Pilatus said angrily: There are enough men around here who claim to be the Messiah. That is not a crime that merits the death penalty. By the way, isn’t he a Galilean? Then he comes under Herod’s tetrarch. He came to your feast in the city. Bring this man to him.

The people grumbled. Why all this fuss? Why the delay?

They led Yeshua, still bound, to Hasmonae palace where Herod, who usually lived in another palace in Jericho or Caesarea, was residing during those days, for he was also a Jew although it was said not of pure blood, but according to belief and circumcision, and therefore he had come to Yerushalayim for the feast. As a Jew he also hated the Romans. As one of the richest and most powerful men in the land he also hated the restless lower classes and all the rebels and all new ideas. Basically he hated everyone and everything. An unhappy man. Since he had had the Baptist beheaded, egged on by his wife and stepdaughter, he knew no peaceful moments. They said that he wandered around the palace at night and saw ghosts who presented him with their heads on silver platters. The thing with this Yeshua was making him nervous again. Could the Baptist have come back? The people at court had already begun to say that the Galilean must be neutralized. But was there a reason for that? There was none. Simply kill him? Not possible either: too many people stood behind that rabbi. Then an opportunity came to smoothly resolve that awkward situation. He and the Romans hated each other. But what did that matter now? If the Romans killed this Yeshua it mattered not at all to Herod. Roman law applied to everyone who lived in a Roman province and (here was an obvious hitch) acted against the Romans, which means endangered state security. Could that be attributed to the Galilean?

It could: He claimed to be the Messiah. And it is said that the Messiah is to be the king of the Jews, and what else does that mean than that he will free Yisrael from the occupying power. If that isn’t talking against the Romans!

What did he say? Exactly! Where are the witnesses?

We, the entire High Council.

Tell me the exact words!

To the high priest’s question if he was the Messiah and the son of God, he answered that he is.

That’s indirect. What did he say directly?

He answered: You say it.

Ambiguous. It can mean: it is as you say, it can mean: you say so, not I.

Jewish pettifogging! Either way: he didn’t answer with a clear no, and a half no is a half yes, and a half yes is an admission.

Well, that can be twisted and turned. My question is: How does that injure Rome, a world power? And here this little Jew. A dog baying at the moon. Let him go, the fool.

He talked that way because he was afraid. He thought differently. But he saw the Baptist’s head in a kind of fog, his hair stood up and his forehead was sweating.

A little Jew, you say. Yes, yes. But he has already been able to win over a mob of followers. There is unrest among the people. Whether it’s this Galilean or another: he could lead an uprising, for there are already disturbances. He must be made an example. If we let him go it will be an opening for the rebels. A different kind of example. Here Erez Yisrael, there Macedonia, there Epirus, there Mauritania, Aegyptus, Hispania, Gallia, Illyrium, Raetia. Remove a beam from the building and it shakes. Colonial peoples need an iron fist. So: are you Rome’s friend or foe? You know: To be Rome’s foe is dangerous, to be Rome’s friend is bearable.

Herod promised to do his best in Rome’s interest.

Bring him to me!

We learned all this from reports. Yochanan had friends everywhere who told him what otherwise remained secret. We also learned in this way how the hearing, or whatever you want to call it, went.

It was as though it never happened, because Yeshua said nothing.

He refused to give Herod a single word.

That confused Herod. The silence was so decided, so definite, so dignified, that it demanded respect. Herod, who had been mentally ill for years, though only sporadically, feared that silence. Apparently he saw before him the forever silent head of the Baptist.

Take this man away! he screamed. Do with him what you will. Out of my sight!

Was that a clear indication for Pilatus? By no means. But Pilatus understood what he wanted from it: that Herod would not stab him in the back. But how did that help him? Herod didn’t condemn Yeshua. He could use that. He’d see how far he could get with it.

So he announced publicly: Herod sent back the accused without condemning him. He didn’t reckon with the uproar this caused. He covered his ears and went back into the house. Such Jewish hubbub wasn’t to his liking. Let them let off steam first.

It must have been then that his wife sent him the message: Free this man, he is innocent, I suffered all night from nightmares and waking thoughts because of him, withdraw from this case, it will cause you misfortune.

Now this. He was terribly confused. Procula was certainly right: the Jews would surely blame the Romans for the death of one of their own. If he allowed this one Jew to live, however, he would be reproached by Rome as a friend of the Jews and coward and who knows what else, at least that, maybe worse. There was much talk in Rome anyway about unrest in Judea and that the governor was incapable of stopping it. Whichever way: disaster. Cursed pack of Jews, cursed land, cursed Adonai, or whatever their god was called.

If he had this Jew who had so many followers executed an uprising could occur, if he didn’t execute him, an uprising could also occur. These people were incomprehensible. Religious fanatics. Strange, very strange, and very dangerous because unforeseeable.

The people in the courtyard screamed: Pilatus! Pilatus!

He came out and in doing so something occurred to him: not the death penalty, not that, but public punishment, a whipping, that was common, the people can look, that would be enough to cool their boiling blood.

He was relived. That was a rescuing inspiration. He thought.

He said: The accused is found innocent of inciting to rebellion according to Roman law. The death penalty will not be applied. He must, however, be punished…

He faltered. For what though?

The people needed not reply. They cried: If he wasn’t a criminal deserving the death penalty we wouldn’t have brought him to you!

Pilatus threatened to clear the courtyard of the Praetorium if there wasn’t quiet.

It became quiet.

Two torturers tied Yeshua to a post, then Pilatus gave the signal for whipping. The whips whistled. They weren’t like our Jewish ones, which were only plaited straps. The Roman ones were wound with lead balls and sharp objects.

I stood so close that I could see how Yeshua’s skin burst. I prayed: Adonai, let him faint, don’t let him feel anything, whip me instead of him.

But Yeshua didn’t faint. No sound escaped his lips. He kept his eyes closed. Pilatus turned away.

The people counted the lashes. Forty was the prescribed amount according to Jewish law. At the thirtieth lash Yeshua sank to the floor, as far as the bounds allowed.

Pilatus gave the sign to stop. He feared that Yeshua was dead. I hoped so.

But the torturers pulled him up and untied him. He stood straight. His naked upper body was bloody and shredded.

I cried out, I cried out his name. Yochanan covered my mouth. Yeshua heard my cry, he opened his eyes. I don’t know if he saw me.

And now Pilatus said the words which afterwards everyone wanted to have heard and whose meaning puzzled mightily.

“Look at the man!”

What did Pilatus mean?

Perhaps this: Look at him, he is no Messiah-king. This is a poor beaten man.

Or this: This isn’t a tough opposition fighter type, this is a lamb, not a tiger, so what are you afraid of?

Or: Look - with how much dignity he bears it all. Respect him.

Or: Look how he has been wounded. Isn’t it enough for you?

For me it meant: Look, this is THE man, exemplar, the highest on this earth.

As Yeshua stood thus between Pilatus and the people, a single voice cried out: He deserves the death penalty. On the cross with him!

An unknown voice. Others chimed in, crude screaming and shouting rose up.

The Prince of Darkness had his hand in the game here, and the people fell into his temptation without really knowing what they were doing.

Pilatus realized that this hate was like a sickness, like a dog’s rabies. He turned away disgusted. Not even the Roman mob acted in that way. Now Pilatus had to take the definitive decision. But again he tried to get around it.

How can I, a Roman, execute your king?

Our king? This one? We have no king except the Roman emperor.

I was ashamed of my own people. How they crawled before the Romans! How they denied wanting a king or even being able to have one.

We have only one ruler, the Roman emperor.

That was a public recognition of the occupier. It was political and spiritual capitulation. I had never cursed before and never after. But I did it then. Yochanan covered my mouth.

Pilatus realized what was happening, but he made one last try to make this awkward, embarrassing, dangerous affair disappear.

He stepped forward, asked for quiet and said: It is my duty to free one political prisoner during the Passover feast. Therefore I wish to free this one.

The people’s answer was one angry shout: Not him, set Bar Abba free!

Pilatus stood once again before a trap: to free Bar Abba would mean giving back to the underground one of their most capable fighters. What would Rome say? To not let him go and instead free this in a sense harmless, on the other hand so unfoundedly hated Galilean, would mean to increase even more the hostility of these fanatical Jews. What to do?

He looked at the beaten man. He was finished, he had learned his lesson. But the strong one, the violent one was still in prison. Free him and he would be back with the freedom fighters within an hour.

Pilatus was afraid, that was obvious. He looked here and there, looking for a helpful sign, he even looked at Yeshua: couldn’t this strange accused utter one word in his own defense, a prophet’s word or something?

Yeshua returned his gaze. I saw it. It was a look which pursued Pilatus and caused him to commit suicide a few years later, as was reported from Rome, to where he was recalled because of his incapacity. Incapacity? What could he have done? Could another do it better?

The one who did it better was called Florus, who came three years later. He did it so well that no stone remained standing in Yerushalayim and God’s people were taken as slaves to Rome. All for one, no: one for all, as Caiaphas had said in the High Council: Better that one dies than that the whole people bear the consequences of a rebellion.

Now the exchange of prisoners took place: Bar Abba was brought from prison. The people cheered, they carried him on their shoulders, the courtyard emptied. Pilatus went back into the Praetorium.

Yeshua stood there for a moment. I called out his name. Now he saw me and Yochanan. But then he was taken away, rather pushed away with kicks, blows and curses.

We could no longer follow him because he was taken through a back gate, and at first we lost the track, until we saw a group of women: Veronica and all the rest, and Yeshua’s mother in the middle. Only women. Where was Shimon, where was Andrew, Philippos, Mathaea, where were they all? Disappeared like weasels, fled like mice into their holes.

Continued in the next issue of SCR.

Translated from the German by Frank Thomas Smith

For the complete book free of charge in pdf format, send a request to [email protected]