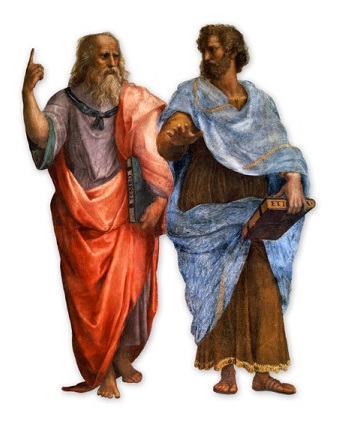

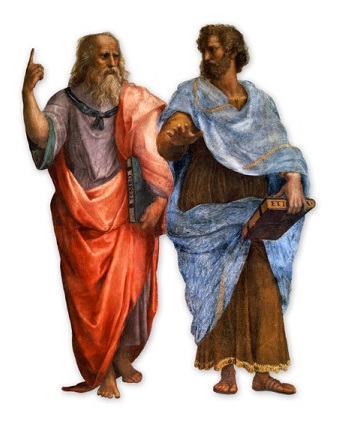

Plato (c. 428–c. 348 BCE) and Aristotle (384–322 BCE) are generally regarded as the two greatest figures of Western philosophy. For some 20 years Aristotle was Plato’s student and colleague at the Academy in Athens, an institution for philosophical, scientific, and mathematical research and teaching founded by Plato in the 380s b.c. Although Aristotle revered his teacher, his philosophy eventually departed from Plato’s in important respects. Aristotle also investigated areas of philosophy and fields of science that Plato did not seriously consider. According to a conventional view, Plato’s philosophy is abstract and utopian, whereas Aristotle’s is empirical, practical, and commonsensical. Such contrasts are famously suggested in the fresco School of Athens (1510–11) by the Italian Renaissance painter Raphael, which depicts Plato and Aristotle together in conversation, surrounded by philosophers, scientists, and artists of earlier and later ages. Plato, holding a copy of his dialogue Timeo (Timaeus), points upward to the heavens; Aristotle, holding his Etica (Ethics), points outward to the world.

Although this view is generally accurate, it is not very illuminating, and it obscures what Plato and Aristotle have in common and the continuities between them, suggesting wrongly that their philosophies are polar opposites. So how exactly does Plato’s philosophy differ from Aristotle’s? Here are three main differences.

Forms. The most fundamental difference between Plato and Aristotle concerns their theories of forms. (When used to refer to forms as Plato conceived them, the term “Form” is conventionally capitalized, as are the names of individual Platonic Forms. The term is lowercased when used to refer to forms as Aristotle conceived them.) For Plato, the Forms are perfect exemplars, or ideal types, of the properties and kinds that are found in the world. Corresponding to every such property or kind is a Form that is its perfect exemplar or ideal type. Thus the properties “beautiful” and “black” correspond to the Forms the Beautiful and the Black; the kinds “horse” and “triangle” correspond to the Forms the Horse and the Triangle; and so on.

A thing has the properties it has, or belongs to the kind it belongs to, because it “participates” in the Forms that correspond to those properties or kinds. A thing is a beautiful black horse because it participates in the Beautiful, the Black, and the Horse; a thing is a large red triangle because it participates in the Large, the Red, and the Triangle; a person is courageous and generous because he or she participates in the Forms of Courage and Generosity; and so on.

For Plato, Forms are abstract objects, existing completely outside space and time. Thus they are knowable only through the mind, not through sense experience. Moreover, because they are changeless, the Forms possess a higher degree of reality than do things in the world, which are changeable and always coming into or going out of existence. The task of philosophy, for Plato, is to discover through reason (“dialectic”) the nature of the Forms, the only true reality, and their interrelations, culminating in an understanding of the most fundamental Form, the Good or the One.

Aristotle rejected Plato’s theory of Forms but not the notion of form itself. For Aristotle, forms do not exist independently of things—every form is the form of some thing. A “substantial” form is a kind that is attributed to a thing, without which that thing would be of a different kind or would cease to exist altogether. “Black Beauty is a horse” attributes a substantial form, horse, to a certain thing, the animal Black Beauty, and without that form Black Beauty would not exist. Unlike substantial forms, “accidental” forms may be lost or gained by a thing without changing its essential nature. “Black Beauty is black” attributes an accidental form, blackness, to a certain animal, who could change color (someone might paint him) without ceasing to be himself.

Substantial and accidental forms are not created, but neither are they eternal. They are introduced into a thing when it is made, or they may be acquired later, as in the case of some accidental forms.

Ethics. For both Plato and Aristotle, as for most ancient ethicists, the central problem of ethics was the achievement of happiness. By “happiness” (the usual English translation of the Greek term eudaimonia), they did not mean a pleasant state of mind but rather a good human life, or a life of human flourishing. The means by which happiness was acquired was through virtue. Thus ancient ethicists typically addressed themselves to three related questions: (1) What does a good or flourishing human life consist of?, (2) What virtues are necessary to achieve it?, and (3) How does one acquire those virtues?

Plato’s early dialogues encompass explorations of the nature of various conventional virtues, such as courage, piety, and temperance, as well as more general questions, such as whether virtue can be taught. Socrates (Plato’s teacher) is portrayed in conversation with presumed experts and the occasional celebrity; invariably, Socrates exposes their definitions as inadequate. Although Socrates does not offer his own definitions, claiming to be ignorant, he suggests that virtue is a kind of knowledge, and that virtuous action (or the desire to act virtuously) follows necessarily from having such knowledge—a view held by the historical Socrates, according to Aristotle.

In Plato’s later dialogue, Republic, which is understood to convey his own views, the character Socrates develops a theory of “justice” as a condition of the soul. As described in that work, the just or completely virtuous person is the one whose soul is in harmony, because each of its three parts—Reason, Spirit, and Appetite—desires what is good and proper for it and acts within proper limits. In particular, Reason understands and desires the good of the individual (the human good) and the Good in general. Such understanding of the Form of the Good, however, can be acquired only through years of training in dialectic and other disciplines, an educational program that the Republic also describes. Ultimately, only philosophers can be completely virtuous.

Characteristically, for Aristotle, happiness is not merely a condition of the soul but a kind of right activity. The good human life, he held, must consist primarily of whatever activity is characteristically human, and that is reasoning. The good life is therefore the rational activity of the soul, as guided by the virtues. Aristotle recognized both intellectual virtues, chiefly wisdom and understanding, and practical or moral virtues, including courage and temperance. The latter kinds of virtue typically can be conceived as a mean between two extremes (a temperate person avoids eating or drinking too much but also eating or drinking too little). In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle held that happiness is the practice of philosophical contemplation in a person who has cultivated all of the intellectual and moral virtues over much of a lifetime. In the Eudemian Ethics, happiness is the exercise of the moral virtues specifically in the political realm, though again the other intellectual and moral virtues are presupposed.

Politics. The account of justice presented in Plato’s Republic is not only a theory of virtue but also a theory of politics. Indeed, the character Socrates there develops a theory of political justice as a means of advancing the ethical discussion, drawing an analogy between the three parts of the soul—Reason, Spirit, and Appetite—and the three classes of an ideal state (i.e., city-state)—Rulers, Soldiers, and Producers (e.g., artisans and farmers). In the just state as in the just individual, the three parts perform the functions proper to them and in harmony with the other parts. In particular, the Rulers understand not only the good of the state but, necessarily, the Good itself, the result of years of rigorous training to prepare them for their leadership role. Plato envisioned that the Rulers would live simply and communally, having no private property and even sharing sexual partners (notably, the rulers would include women). All children born from the Rulers and the other classes would be tested, those showing the most ability and virtue being admitted to training for rulership.

The political theory of Plato’s Republic is notorious for its assertion that only philosophers should rule and for its hostility toward democracy, or rule by the many. In the latter respect it broadly reflects the views of the historical Socrates, whose criticisms of the democracy of Athens may have played a role in his trial and execution for impiety and other crimes in 399. In one of his last works, the Laws, Plato outlined in great detail a mixed constitution incorporating elements of both monarchy and democracy. Scholars are divided over the question of whether the Laws indicates that Plato changed his mind about the value of democracy or was simply making practical concessions in light of the limitations of human nature. According to the latter view, the state of the Republic remained Plato’s ideal, or utopia, while that of the Laws represented the best that could be achieved in realistic circumstances.

In political theory, Aristotle is famous for observing that “man is a political animal,” meaning that human beings naturally form political communities. Indeed, it is impossible for human beings to thrive outside a community, and the basic purpose of communities is to promote human flourishing. Aristotle is also known for having devised a classification of forms of government and for introducing an unusual definition of democracy that was never widely accepted.

According to Aristotle, states may be classified according to the number of their rulers and the interests in which they govern. Rule by one person in the interest of all is monarchy; rule by one person in his own interest is tyranny. Rule by a minority in the interest of all is aristocracy; rule by a minority in the interest of itself is oligarchy. Rule by a majority in the interest of all is “polity”; rule by a majority in its own interest—i.e., mob rule—is “democracy.” In theory, the best form of government is monarchy, and the next best is aristocracy. However, because monarchy and aristocracy frequently devolve into tyranny and oligarchy, respectively, in practice the best form is polity.

From the Encyclopedia Britannica