I watched the Academy Awards presentations last night (February 24, 2019) until 1 o'clock in the morning because Argentina is two hours later than Eastern Standard Time in the U.S. I was falling asleep partly from boredom and partly because of the late hour, when the film “Green Book” was announced as the surprise winner of the Oscar for best picture.

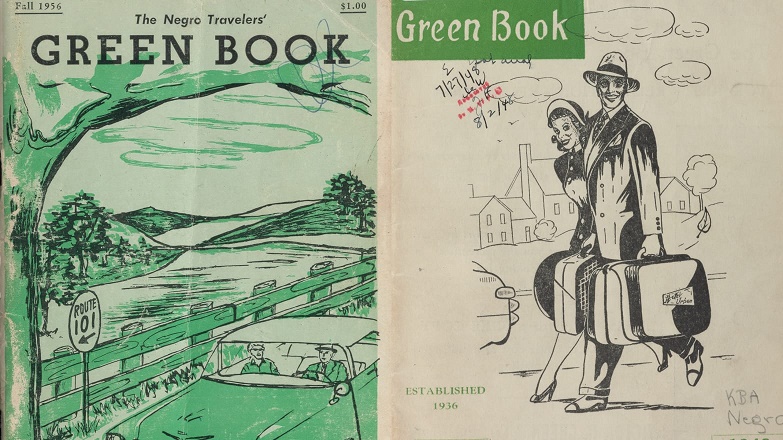

I had seen the title before but thought it had something to do with ecology. Now, as I watched the TV screen, it morphed into a book I had known well many years ago: The Negro Traveler's Green Book.

I was born and grew up in Brooklyn long before Spike Lee and Barbara Streisand. Brooklyn was segregated, not because the law said it must be – but because it just was. I lived in Flatbush, which had some Black people (then called Negroes or Colored). Brooklyn's real Negro neighborhood was called Bedford Stuyvesant. It wasn't particularly poor, rather black middle class, populated at first by families who had moved there from an overcrowded Harlem.

Growing up, the only black people I saw were the janitors who took care of the apartment house furnaces and lived in small rooms in the basement from Monday through Saturday and went home to Bed-Stuy on Sundays. The exception was the janitor in one of the larger buildings who lived there with his family. His son, my age, sometimes played stickball with us. He didn't stick around after games though, so we never became friends. No one thought anything of it; it's just the way it was.

Most of my friends, except for the Jews, went to Catholic high schools. My parents couldn't have cared less if I went to a Catholic or public school. Upon the recommendation of a friend, I took the entrance examination for Poly Prep high school and although I didn't fail, because their ability to accept new students was limited the test was competitive, so sorry kid. Much later I found out that Poly Prep was a Jesuit school, so all I can do is thank my ignorance for sparing me that ordeal. Who knows what would have happened if I'd been brainwashed by such experts? But Erasmus Hall, the public school I attended for all four years of high school (as did Barbara Streisand, Spike Lee and Bobby Fisher), did have some Negroes, notably the star of the basketball team. I didn't ask myself why there were so few; it's just how it was.

I went to college for a while in Vermont, where I don't remember ever seeing a black person. Maybe there were none. But let's skip closer to my Green Book. In 1951 or 52 I was drafted into the U.S. Army. It was during the Korean War, but that didn't worry me much, I was glad to get away from my Wall Street job as assistant insurance underwriter and, as most young people, I considered myself immortal. I was sent to Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky, for basic training, where there were a few Blacks in my company, neither more nor less than the national average. Towards the end of basic training, I was called to the Classification and Assignment Office at the other end of the camp. There I was told, together with a dozen other grunts, that we had been selected, based on the IQ test we had taken during the first week in the army, to attend the Army Language School at the Presidio in Monterey, California for one year. The sergeant who informed us of this paused to let our hearts begin to beat again. You must realize that this was during the Korean War and the Chinese had recently invaded from the north. The situation was so dire that President Eisenhower had canceled all leaves for training companies (like ours) in order to get us into the battle in Korea as soon as possible.

Apparently those of us now listening to the C&A sergeant had high IQ scores and thus were intelligent enough to understand that Korea was not the safest place to be. Actually, you didn't need a high IQ to understand that. For example, the only trainee in my company who volunteered for the “elite” newly formed Special Forces was a kid we called Dumbo, and not only because of his big ears. So we were most pleasantly surprised at the opportunity to spend the next year in Monterey instead of a foxhole.

However, continued the sergeant, if you sign up for the School you must reenlist for three years – double the draftee length of service, of which some of us (we came from different companies) had already completed three months. But no one left, yet. We could choose between the following languages: Swedish, Russian, Chinese Mandarin, Japanese or Korean. Swedish?! You gotta be kidding, as we thought of Ingrid Bergman-like Swedish girls. He handed out forms in which we were to write our names, serial numbers, etc, and first three choices of languages. Clearly the obvious choices for any red-blooded, non-heroic American boy would be Swedish, Russian and Chinese or Japanese (flip a coin) – thus avoiding Korean as though it were a venereal disease. The forms were duly collected and we were told we'd be called back in a week or so. I, without telling anyone for fear of being judged imbecilic or queer (“gay” hadn't been invented yet), chose Russian first because I was on a Dostoevsky kick and was excited at the possibility of reading him in Russian.

When he called us back, the sergeant gleefully informed us that the only hero who got his first choice was Yours Truly, because the Swedish class had been filled by the time our applications arrived at the School. Furthermore, Russian, Chinese and Japanese had also become full and the only language left was Korean. Several stood up and left and the others signed up for Korean, hoping that the war would be over by the time they learned the language. Either way, the sergeant was kind enough to add, a Korean linguist would not be fighting on the front lines.

I spent a year in Monterey, California at the Army Language School studying Russian six hours a day, five days a week. We wore uniforms, there were very few officers (too dumb?), no saluting or yes-sir, no-sir crap. It was like a university campus with free (excellent) food.

Jim McKay wasn't in my barracks, but he was in my Russian class. He became a friend, of sorts. I say “of sorts” because it was not possible those days for a true bi-racial friendship to endure – and Jim was Black. What we had in common was jazz, especially the “Divine Sarah” Vaughan. We went to a bar situated on the road halfway up to the Presidio. It was mostly patronized by soldier-students from the School. It had a jukebox on which we could play all the Sarah Vaughan we wished for a nickel a song. We didn't go anyplace else together though, except occasionally for lunch at a Mexican place in town on Sunday. When I went bar hopping on Saturday nights drinking lots of beer and hoping to pick up a girl, I couldn't ask Jim to join me, nor would he have accepted if I had, because it would not only have been unusual, but even dangerous. Oh, Jim would have been served, Monterey wasn't the South, but the young townies didn't like soldiers, especially not Language School soldiers, and for one to appear accompanied by a black soldier would have been considered arrogant and looking for trouble. And naturally the hunt for feminine company would have been completely hopeless. That's just the way it was. I also never took him to San Francisco with me, where I went about once a month, for the same reasons.

We had a month's leave coming when the language course ended, after which we were to ship out from New York to Germany. We were given money to buy air transportation to New York, but in order to save the money I got a ride with a sergeant who was driving his own car and wanted passengers to share the cost of gas. I told Jim, who was from Washington, DC, and he jumped at the chance to save all that money. I sold my old Hudson Hornet, which wouldn't have made it to Arizona let alone the East Coast, for $50, the same amount I'd bought it for a year before.

The sergeant – I forget his name, so I'll call him Hans – was a German Jew, accent and all, who was now an American citizen. He was older than us, perhaps thirty, with a stocky build and a crew cut. Obviously, with three languages (at least) now, he would be a valuable investment for Military Intelligence.

The morning we were set to leave, already in the car, Hans put on the radio and the Breaking News was that there were furious snow storms and subzero temperatures across the Midwest, where motorists were advised to stay home. That was the route we´d planned to take, with the best and most direct highways, but now...Hans opened his map and studied it, then said, “we can go through the South, no storms there.”

“It could be a problem for Jim,” I said, “you know, with hotels and stuff.”

“You guys can also drive, right? We could drive straight through,” Hans said. “Jim?”

“Okay by me,” Jim said, after a short pause. To better understand this truly mistaken decision, you have to realize that we were in a hurry to get home. We had a month's leave before shipping out, but didn't want to waste any of it traveling. Also, there was nothing like the “Green Book” movie then, and we had no idea what we would be facing in the deep South. That was even before Martin Luther King.

Our first stop was somewhere in Arizona to repair a flat tire. Hans stayed with the car and Jim and I went to a bar down the block. It was empty. “Two beers, please,” I said to the bartender. He looked up at me, then at Jim, then back at me: “We don't serve colored people here.” It felt like being punched in the stomach. Arizona! This wasn't the South, it was the wild west – in our innocent imaginations. We left and went back to the car.

Approaching Albuquerque, New Mexico, we saw a motel “for colored guests” on the road. Motels always sprung up like mushrooms outside of cities. We were exhausted. Hans's idea of driving through was not practical. You can't really sleep sitting up in a bouncing, noisy automobile, day or night. Drowsing ain't sleeping.

“Let's look here,” Jim said.

It was a clean, well-kept, comfortable motel. The owner, a middle aged black lady, told us she had rooms for all three, no problem. The next morning at breakfast – delicious by the way – the lady asked if we were heading East through the deep South. We were.

“Well, in that case, you might be interested in the Negro Travelers' Green Book.” She took a copy from her apron pocket and handed it to Jim. “This is the last place you three boys will be able to stay together in motels or even restaurants,” she went on. “This here little book is really invaluable for any colored person traveling through the South. It'll show you where to find hotels or motels and restaurants that cater to Negros. The South is completely segregated, don't forget it.”

All during the trip we had to eat three times a day. Jim, however, was not permitted to enter restaurants with us, even if they were total dumps. So Hans and I would go in, take three meals to go and we'd eat together in the car. Such restaurants were usually combined with service stations where we tanked up and went to the toilette. Even that wasn't easy though. The rest rooms were for “white only” and “colored only”. Even the drinking fountains were segregated. That's just the way it was.

The next place we stayed overnight was Jackson, capital of the state of Mississippi – about as deep South as you can get. Jim opened the Green Book and found only two addresses, both on the same street. Despite being the state capital, Jackson wasn't a very big city. Nevertheless, we needed information on how to find those addresses. It was already after dark and the town looked very quiet. We saw a diner up ahead with all the lights on. We stopped in front of it and I got out of the car and entered the diner. I was nervous, but didn't know why. Hey, I told myself, I'm a white boy: No problem, right?

There were about a dozen customers in the diner, all men, three or four at the counter, the rest in booths. The heat and the smell of frying food hit me. The counterman handed me a menu and greeted me as “Sir”. Thanks, I said, but I wonder if you could tell me where “L” Street is. (I don't remember the street's name.) His smile disintegrated like an ice cube on a griddle. “Not sure,” he said. Then, out loud to everyone, “Anyone know where “L” Street is?” All heads turned and all eyes concentrated on me.

“Yeah,” a guy in a booth said, “it's in niggertown.”

“Can you tell me how to get there?”

He looked out the window: “That yo car out thair?”

“Yes.” He couldn't see inside the car.

He stared at me for a few seconds, then said: “Okay then, go straight about ten blocks to the traffic light, turn right and ya should get to it in a few blocks.”

“Thank y'all kindly,” I muttered, trying to sound like him, and left quick.

The first hotel in the Green Book was a two-story rundown wooden building in a rundown Negro neighborhood. The second was a few blocks further and looked even more rundown, so we went back to the first one. We parked and Jim went in. He came back a few minutes later and handed me his wallet to hold just in case. Hans said we'd pick him up early the next morning. I doubt he slept very well that night. We drove back out of town and checked into a nice motel Hans had noticed on the way in. As we watched Jim walk back into that dump I felt like crying, in sympathy yes, but also for shame.

The next morning we returned to Jim's hotel and I went in to get him. He was sitting in a chair across from the desk waiting, He stood up and shook hands with the guy at the desk, who said, “Good trip, brother”.

The next stop was in Macon, Georgia. The hotel was in a better Negro neighborhood than the Mississippi one, and the hotel looked like a real one, shabby but real. The next day we finally got to Washington and Jim got out on the outskirts, saying he knew where he was and would take a bus right to his doorstep. Sergeant Hans and I drove the rest of the way to New York the same day. Hans left me off somewhere, I forget where, and I took the subway home to Brooklyn.

Thirty days later I boarded a “liberty” ship, one of those old second-world-war bobbing buckets. I don't know if Jim or Hans was on the same ship because I was too busy being sea-sick for the two-weeks journey to the port of Bremerhaven in Germany. There another Classification and Assignment office sent me to a Military Intelligence unit in Frankfurt. I never saw Hans again, but I did run into Jim McKay in the halls of the I. G. Farben building which we had taken over to use for offices of the many members of the U.S. Intelligence community. I asked him if he was also stationed in Frankfurt and working in the I. G. Hochhaus, as we called it.

“No man,” he said. “I'm down in Heidelberg, great city.”

“I suppose you can't tell me what you do there...”

“Why not, Frank, you got a top secret clearance, don't you?”

When I nodded, he explained that he was a truck driver.

“What?” I exclaimed. “A truck driver with a top secret clearance?”

“Yeah man, Negro, colored, whatever you wanna call us. Truck driver fits, right? This army, especially so called intelligence, is full of southern redneck crackers.”

I didn't know what to say, so I just looked down at my shoes.

“Best goddamn job in this muddafuckin army, Frank my brother,” Jim had pulled me aside out of the flow of pedestrians alongside a cigarette vending machine. “I drive a truck full of confidential supplies (he winked, because he knew that I must know that confidential supplies meant whiskey and cigarettes and such stuff to make our spies, as well as theirs who we caught, amenable to work and/or talk. Most of it wound up on the black market for someone's benefit, who knows whose). “I drive to Berlin through East Germany on the only permitted autobahn corridor, along with a co-pilot, on Monday, unload and return on Tuesday, sometimes empty, sometimes not. Wednesday I'm off. Thursday we go again to Berlin, sometimes more often if the weather doesn't let the planes get in. I decide whether to return to Heidelberg on Friday or spend the weekend in Berlin.” He laughed a deep throated laugh he'd picked up in Germany. “Frankie, the Fraüleins love my black ass.”

And that's the way it was.