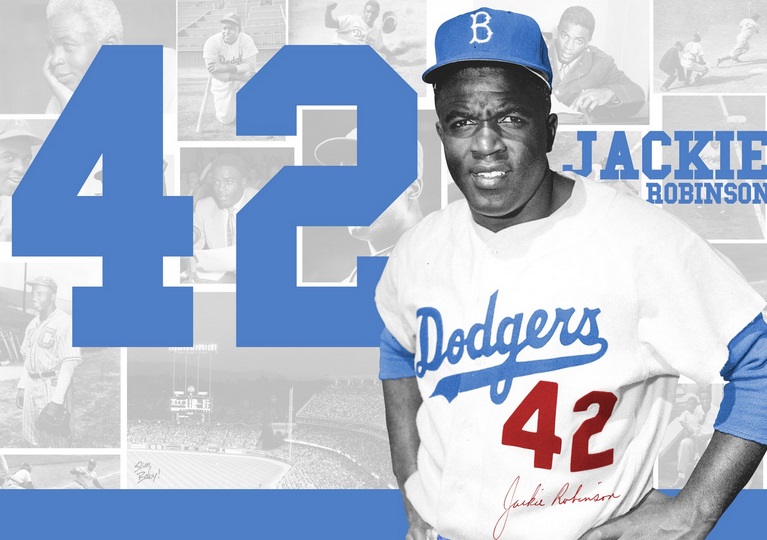

It's Jackie Robinson Day! All the major league baseball team players have his number – 42 – on their backs. Well, why not? Jackie was not only one of the best baseball players who ever lived, he was, more importantly, the first African American (called Negro back then) to play in the Major Leagues, for the Brooklyn Dodgers. He took a lot of racist insults – not in Brooklyn, in the South – which he knew he would, but never blew his top. It's not a national holiday yet, but somehow better.

As I watched the ceremony honoring his memory on TV, another personal memory came to mind: why they call me Jackie Robinson in Brazil.

*

Sometimes I woke up and didn't know where I was and what language I should say good morning to the maid in. I'd eat breakfast, usually alone, sometimes with my mother if she didn't get to bed late the night before, and head for school in a bulletproof, chauffeur-driven limousine with my two bodyguards. In case you didn't know, the United States is a big, unloved country that likes to throw its weight around so American companies can buy the world and the so-called Third World is full of assholes who think they can change everything by kidnapping the American ambassador's son.

I had this recurring dream. I'm spread-eagled naked on a cot in a dingy basement room. The terrorists decide that the only way to convince the United States to give Texas back to the Mexicans is to cut off my balls and send them to the White House with a note graphically stating what would be next. A hairless albino is approaching me with a hacksaw when I wake up screaming.

I thought what good is being an ambassador's son if all those assholes want to emasculate you to prove they mean business and you have to be surrounded by bodyguards all the time. Also, I had a lot of discussions with my father about our supporting a military government whose hobby was "disappearing" anybody who didn't agree with them. He said it was all part of the war against communism -- the usual bullshit. So I decided to quit being the ambassador's son, at least for a while.

That involved running away, which wasn't as easy as it sounds. A squad of Marines, a local security company and the police guarded the residence in Buenos Aires and my two bodyguards always followed me like shadows. I had the advantage of surprise though, because they were there to protect me and weren't expecting me to want to escape.

I gave them the slip in the movies, where I went with the Liberian ambassador's daughter. "Look amigos," I said to my bodyguards, "I want to make out a little in the dark, so why don't you guys sit way in the back so I don't get nervous from you breathing down my neck." The movie was with that Schwarzenegger meatloaf, just what they liked, and it served to distract them. I told the Liberian girl to tell my mother that I was fed up with being the ambassador's son and the stupid American school I had to attend and I was taking a vacation for a while -- just so they wouldn't think I'd been kidnapped and have my picture spread over every goddamn newspaper in the world.

I took a taxi to the city airport, which has domestic flights and some to neighboring counties; flights to and from more distant countries were at the international airport twenty miles from the city. I boarded a flight to Sao Paulo, Brazil. You'll probably ask why there, why not just lie low in Buenos Aires, which is as big as New York and just as easy to disappear in. Well, there's something I haven't mentioned yet. I'm black and my father was the only black American ambassador in the business. I don't want to get into racial shit here, but the fact is that Argentina has hardly any blacks to speak of. There used to be a lot, brought over from Africa as slaves, but they got killed off by cholera epidemics and fighting as conscripts in all the Indian wars they used to have, so I stuck out like a sore thumb. Also, I'm pretty well known because I dated some of the lily-white Argentine society girls and the newspapers thought that was news, which it was, because for an Argentine girl to date a black guy is like putting the purity of their fucking race in danger.

So, firstly, my best bet was to get out of Argentina so I wouldn't be recognized. Secondly, in Brazil every other dude is black, so I'd not only not be recognized there but would blend in colorwise as well. Thirdly, I knew a place to go where they'd never think of looking for me: a favela, which is Brazilian for a shantytown. And fourthly, I speak fluent Brazilian Portuguese, better even than Spanish, because that's where my dad was stationed last and I spent some very formative years there.

When my father was ambassador to Brazil we visited a favela once in Sao Paulo because the U.S. government donated some computers to a school there. He wanted to show me how generous we were and how we were helping the poor and all that crap, when actually all were doing was making it worse. I mean they're starving so we give them computers. During that visit we saw some young people there: Germans, a Swiss and even a couple of Americans who worked temporarily as volunteers. I intended to offer myself as a volunteer there until I got tired of it.

Dona Ute (pronounced oo-teh), the woman who ran the school, lived in a house that wasn't much better than the ones in the favela. It was perched on a hill overlooking the avenida, which meant you couldn't hear yourself think because of the racket the buses and cars made. There was no bell so I clapped my hands, which is what you do in Brazil when there's no bell.

I remembered her, though I knew she wouldn't remember me. She barely looked at me back then, because everyone was so excited about the American ambassador, thinking it was a big deal, which it wasn't. My father never said a word to the favela people, he didn't even look at them. He talked to Dona Ute a little, but mostly he hung onto the Mayor of Sao Paulo, who's now in jail on a money laundering charge, and the press of course. Dona Ute wasn't old or anything, but she looked kind of bedraggled, like something the cat dragged in. But I admired her a million times more than those ambassadors' wives who always look like they just stepped out of a beauty parlor.

I was tempted to say I was Brazilian, but decided it wasn't a good idea because there are always little things that can give you away if you're not a real native, like who won the soccer championship in 1940, because soccer is a subject Brazilians are absolutely nuts about. I knew who Pelé and Maradona were and that's about it. I really like baseball, but what good is that in Brazil where they wouldn't recognize a fast ball if it hit them in the face. So I decided to play it safe and say I was an American who lived in Brazil a number of years until my father, a missionary, got transferred back to the States and now I'm a student doing my thesis about the Brazilian favelas. Pretty thin, when I think about it now, but they swallowed it.

"You know that we can't pay you," Dona Ute said, "except carfare if you have to go someplace for us."

"That's all right, I don't need money."

"Your Portuguese is very good. Do you know other languages?"

"English of course."

"Of course."

"Then there's Spanish, German, French, Hindustani. That's about it."

"Enough," she laughed. "How did you learn all those languages?"

"Oh, my dad was stationed all over the place and I just picked them up. Kids can do that, so I'm not bragging"

"Yes, I know. I also led a nomadic life as a child," Dona Ute said. "My father was a scientist and we lived in many different countries. I think that being rootless as a child does something to you. In a sense it's positive; in another sense it deprives you of something."

"In your case it was positive," I said.

She sighed. "Please don't think I'm some kind of Mother Teresa. It isn't true and I wouldn't like it."

"OK, I won't." But I did.

"We'd like to send our appeals to more places in the people's own languages," Dona Ute said. "Maybe you could work in the office and do that."

"Sure," I said, really pleased, because I wasn't looking forward to wiping kids' asses all day.

"One or two days a week. There are other things to do outside the office."

"Oh sure, I wouldn't want to be cut off from the real work."

"That's the spirit," she said, and I knew I had made a good impression.

"Oh, by the way, what's your name?"

Believe it or not I wasn't prepared for that question; I only hesitated for a second though.

"Jackie."

"Jackie what?"

"Jackie Robinson."

It was inspiration. I realized too late that it could draw the attention of Americans looking for me, but once I said it I was glad because I really loved that guy. And like I said, Brazilians aren't interested in baseball, so they wouldn't recognize the name of the first black player in major league history.

A Brazilian guy name of Zeca, a couple of years older than me and a political science student, worked in the "office" – just a shack tacked into the school – doing most of the administrative work. He looked like a mixture of all the races in the world. I helped him with letters in other languages. He asked me a lot about the States, especially the condition of blacks. My family is very integrated into white society. I mean we hardly even know any blacks, except for my relatives. What I told him was more than he knew though, and he seemed satisfied. He asked me what I thought about the social situation in Brazil and I told him it was terrible, that's why I was there, to help with what little I could, which was bullshit of course, but he believed me.

One day when we were alone in the office he said, without looking up from what he was doing, "Hey, Jackie, do you think what we're doing will change anything?"

It was a good question, one I hadn't considered before. "We're helping the kids in this favela," I said.

"Wake up, Jackie. Brazil has about 130 million people and two-thirds of them live like animals. So what good is helping a few people in one privileged favela?"

"Why do you work here then?"

"Because I used to think like you, that it's better than nothing and now I'm here and I'm not so sure any more."

I didn't say anything, not that I had anything to say anyway.

"I like you, Jackie. You're a gringo, you can't help that, but at least you're black and you've got a social conscience or you wouldn't be here." He turned back to his work, but I suspected he'd have more to say about all that soon, as I was right.

I got to know a lot of people in the favela, but the most important person for me was Mireya, a black girl of only fourteen, but girls mature early there. The guys said she was stuck-up. I thought that too until I saw her with the kids in the kindergarten where she worked as an assistant. I fell in love with her, which was wonderful, but it complicated things considerably. In order to get to work in the kindergarten I told Dona Ute that I was crazy about little kids, which wasn't exactly true. I have this little brother that I'm not too crazy about because, frankly, he's a spoiled brat. I guess that's not his fault though, considering the rest of my family. My real reason was to be near Mireya. It was kind of rough at first because favela kids aren't spoiled, they're rotten. If one of them gets his hands on a toy you can't get it away from him without threats. And what manners! They eat like it was the first time they ever saw food. But I guess if you were always hungry you'd act the same way.

I started to walk Mireya home, with the excuse that she could tell me on the way about how I could improve my work in the kindergarten. She lived with her mother and uncle and four smaller brothers and sisters in a miserable hut in the favela, but at least it was clean, which is more than you could say for most of the others. You think that favelas are dangerous, right? Well they are. Drug dealers, thieves, murderers, you name it. Not the majority though. Believe it or not, the majority of people who live there are honest and religious. Their religion is weird though, being a mixture of Macumba, which is a kind of good voodoo, and Catholic. But there are a lot of low-lifes around, so it is dangerous. But not for Dona Ute's people. We could come and go as we pleased and nobody bothered us. That's because they considered Dona Ute to be some kind of saint. And it's not smart to mess with saints. The crooks even gave her a computer (stolen of course), which she didn't accept because she thought she could be encouraging crime by taking it. When Zeca found out he told them to put it in the office and he'd handle Dona Ute. His way of handling her was not to mention it. She saw it there but she didn't say anything either. After all, a donation is a donation. Zeca said we accepted donations from companies who exploit the poor and even from the United States, who are imperialists, etc., so why not from a poor favela thief who only stole from the rich.

One night I took Mireya to see a movie. We went to a pizza parlor afterwards and I asked her how much school she had and she said primary school.

"Don't you want to go to high school?"

"Yes, of course, but I have to take care of my brothers and sisters because my mother works all day."

"What does she do?"

"She's a maid for a rich family."

Rich is relative, because for the favela dwellers everyone who lives outside the favela is rich. But rich or not, they all have maids, because in Brazil you can always find someone poorer than you who's willing to work for next to nothing.

"That's too bad," I said, "because if you don't go to high school you'll probably end up being a maid, too."

"What's wrong with being a maid?"

"Nothing. If you think they're so great you can be one.”

She cried then, which made me feel sorry for what I said, especially when she explained that she didn't have money for carfare or books.

"Look, Mireya," I said, "maybe something can be worked out for you to go at night. Did you ever talk to Dona Ute about it?"

"She says I should go to school too."

"Don't they give you any money for working in the kindergarten?"

"Yes, but I give it to my mother. Besides, the night school is two hours away by bus. I'd have to spend four hours just traveling."

"That's because it makes so many detours and stops at every puddle. If you went in the minivan..."

"The minivan? But I can't drive, I'm too young."

"I'm not." I smiled and put my hand on hers, the one that wasn't holding a piece of pizza.

"You'd take me to school every night?"

"Sure, why not?" I didn't have a Brazilian driver's license, only my Argentine one, but that's valid in Brazil if you're a tourist. It's under my real name, but I didn't expect to get stopped because I drive real careful compared to Brazilians who drive like maniacs. Besides, the only reason the cops stop anybody is to shake them down, so they wouldn't be interested in a black kid driving a favela-school minivan.

Mireya said OK, but one night a week she couldn't go to school because she had to go to a meeting. It was the same meeting Zeca had invited me to, which I suspected was revolutionary stuff. I didn't want to get involved in that because of who I was and probably because I didn't really care much what happened in Brazil. I had put him off, saying I'd think about it. Now Mireya asked me why I didn't want to go and I said I'd been thinking about it and maybe I would.

Dona Ute not only agreed to lend us the minivan but also said the school would pay for Mireya's books because it was important that future teachers have a good education. So Mireya enrolled in night school and I took her there every weeknight except Thursdays, when we went to Zeca's meetings. During the three hours I had to wait for her on school days, I went to a cafe and read books or wrote this sort of diary. I threw a lot away, the boring stuff. Maybe I shouldn't have, but I don't like to read boring stuff, even if it's written by me. But there is one thing I'd like to mention, even though it doesn't have much to do with what happened later, I mean the kidnapping and all.

One day just before Easter, Mireya asked me if I was going to the Santa Ceia.

"What's that?"

"Come to the Escolinha" -- that's what they call Dona Ute's school -- "at seven o'clock. You'll see."

The Escolinha was a big barrack-like prefab that they'd fixed up nice by painting it and hanging pictures and with plants and so forth. I didn't hear any noise as I approached at about seven-fifteen, so I thought there was nobody there yet. But when I pushed open the side door I walked into a full house. Cido, a young favelado who worked in the carpentry shop, was standing dressed like a priest behind a table covered with a blue cloth. I thought it must be a play, which they were fond of doing, so I sat down at a table near the door and watched. At the same table, or altar I should say, but seated, was Dona Ute and at either side altar boys stood straight like bookends.

Cido was finishing reading something. He handed the book to the boy on his left, who read falteringly. It was the Bible and he was reading about Jesus being condemned to die. Then he passed the book to the boy on his right, who read about Jesus' resurrection. When he finished Dona Ute held up a large photograph of a boy. She said that the boy had died in an accident and his father, a lawyer, didn't know what to do with the insurance money he received because he didn't need it. Then he heard about Dona Ute's work so he sent the money to her and that's how they were able to buy the land and put up the prefab that served as a school. She asked us to pray for the boy and his father. Cido closed his eyes and said a prayer and everyone closed their eyes and bowed their heads, so I did too. I wasn't really praying, but I didn't want to be the only one staring into space. Then what really surprised me was that Cido took some bread from a basket and said "This is my body", then he lifted up a glass of what looked like wine and blessed it and said "This is my blood." Then some kids with baskets went around putting a piece of bread in front of each person sitting at the tables. We already had empty glasses, most of them chipped, in front of us, and more kids came and filled them with wine. At first I thought it was funny that they were giving those little kids wine, but when I tasted it I realized it was water with about one drop of wine in it. Well, we all ate the bread and drank the wine, but it was like a party, people talking and laughing and everything.

I know what a mass is, because they tried to bring me up Catholic, but what I witnessed in the favela was what it might have been like way back when people still remembered Jesus and it hadn't yet been turned into a torture for little kids where you have to confess how many times you jerked off before you can eat a little piece of dry bread and you don't get any wine at all.

I asked Dona Ute about it afterwards. She told me how there was a shortage of priests in Brazil so in many towns the oldest son in a respected family plays the part. They don't consider it a mass really, she explained. I said no, it's better. She just laughed and changed the subject.

Mireya and I got a lot closer, but even when we were alone in my room I never had sex with her, although I guess I could have. We kissed and I fondled her breasts and kissed them. They were like little brown apples and tasted a million times better. I told her I loved her and she smiled and touched my cheek and said she loved me too. Dona Ute said she hoped my relationship with Mireya was a responsible one, that she was only a child and all that. I said sure, not to worry, and it was true, I wasn't lying about that. I mean what we were doing was kid stuff compared to what goes on.

On Thursday night we went to Zeca's meeting. Zeca made a big deal about me being there, saying I was a black gringo with a social conscience and I would be a welcome and invaluable addition to the group. Zeca could talk, no doubt about it. They went on about why the poor were poor and what Karl Marx said about it and what a great hero Che Guevara was and all that crap. I sat there not saying anything until Zeca asked me what I thought. I should have kept my trap shut, but I have this problem that whenever anyone asks me what I think I tell them.

"It's interesting," I said, "but so what? I mean what can we do about it?"

"We have a plan," Zeca said, and exhaled a perfect smoke-ring. "We're going to kidnap the American ambassador's daughter."

I didn't physically fall off my chair, but mentally I did.

"It's a bold move," Zeca went on, "but we must do something bold to show that we exist and that we mean business."

"But why her?" I knew her pretty well. She was a couple of years older than me, a student at some Ivy League University. She thought she was hot shit because she was older and pretty and white and could beat me at chess, but that's only because she had been stationed in Russia where they learn to play in school. I would have liked to do something else with her besides play chess, but she never paid much attention to me, maybe because she wasn't too keen on crossing the color line.

"A friend of mine who's an exchange student at the university she goes to in the United States knows her," Zeca explained. "He says she has a social conscience."

I doubted that very much.

"Look," Zeca went on, excited, "we bring her to a safe house and explain the situation in Brazil to her. We don't hurt her or ask for money or anything like that. It's a purely political act. Her disappearance will make world headlines. Then we release her and she tells the world what we want."

"And what's that?"

"Justice, a new order, democratic socialism."

"How are you going to kidnap her if she's in the States?"

"She comes to Brazil during vacations."

"Does she speak Portuguese?" I didn't think she did.

"We're not sure. That's why we need you, Jackie. What do you say?"

"I think it's crazy," which was my honest opinion. "Count me out." Then came the touch that changed my life. Mireya put her hand on my knee, which was bare because we all wore shorts and said, "Please, Jackie, at least think about it."

But the more I thought about it the crazier it seemed. "Let's suppose you succeed in grabbing her. What do you do with her? The Brazilian police and armed forces will be looking for her, not to mention the CIA, FBI and a million people looking for the reward they'll offer."

"We have a place where they won't find her."

"Where?"

"He's not one of us," a big black guy protested, "not a Brazilian who feels with our suffering people."

"Che wasn't a Cuban," a cross-eyed white girl said.

"No, and who knows how long it took to convince him," Zeca ageed. "But once he decided to help he became the heart of Latin American revolution, transcending Fidel, just because he wasn't Cuban." He looked at me as though he thought he was Fidel Castro about to recruit Che Guevara to the cause. "This may be the beginning of the liberation of your own people, Jackie."

"Where are you going to hide her?" I asked, still hoping to convince them that the idea was crazy.

"In a fazenda an hour's drive from Sao Paulo."

"So what's so secure about that?" A fazenda is a Brazilian farm.

Zeca looked at a big hairy white guy sitting next to him, who nodded. "It belongs to the Commanding General of the Sao Paulo Military Area."

"Zeca, are you trying to tell me that a general is in with you on this?"

"No, and he hasn't been to his fazenda in three years. His son, Socrates," --he indicated the white guy with his head -- "lives there."

I didn't know what to say. If they could really hide her in a general's house.....

"Would she see our faces?" I asked.

"Of course not. We'll be masked."

I should have stood up then, said OK, count me in comrades, and gone straight to the airport to take the first plane to Miami. But I didn't. Instead I asked how they planned to get the ambassador's daughter to the fazenda.

"Are you with us, or not?" Zeca asked. They were all staring at me expectantly, especially Mireya. Zeca had told me where they planned to keep the girl, a show of confidence on their part. My main concern was what Mireya would think of me if I said no; second was whether they'd let me walk out of there knowing what I now knew.

I gave the thumbs-up sign, which means the same in Brazil as it does everywhere else, except that in Brazil everybody's always using it. Zeca smiled and gave it back to me and so did the rest and we all sat there like idiots with our thumbs up.

"She lives in Brasilia when she's here of course," Zeca explained, "but comes to Sao Paulo often and stays with a Brazilian boyfriend. We watch the boyfriend and when they go out at night we wait for the right opportunity and when it comes, well, it shouldn't be too difficult."

"What about bodyguards?"

"There's only one and she usually gives him the slip. He doesn't say anything, probably because it would cost him his job if he did, or maybe he doesn't mind having some time off."

We had the minivan because it was a school night and Mireya rode huddled close to me on the way home. I asked her up to my room, even though it was late, and we went to bed. But I didn't do anything if that's what you're thinking. What the hell, she was only fourteen and I had promised Dona Ute.

A month passed and nobody said anything about the kidnapping. Mireya even went to school on meeting night. I hoped they'd decided the idea was too crazy and had given it up; but that was wishful thinking.

"We got the girl," Zeca told me one day when we were alone in the office.

"What girl?" I asked, hoping it wasn't true.

"The ambassador's daughter, stupid." And he laughed like the maniac he was.

"How?"

"In the movies. The theater was almost empty last night. When the movie ended the boyfriend left her in front of the theater while he went to get his car that was parked on the next street. All we had to do was push her into the minivan before he got back and drive away. I don't think anyone even noticed it."

"You used the minivan?"

"We covered up the name," Zeca smiled. "Don't worry."

"So she's at the fazenda now?"

"That's right. And she doesn't speak Portuguese."

"How do you know?"

"I asked her."

"Maybe she was lying."

"Why should she lie about that?"

I didn't know.

"Tonight after you take Mireya to school you go right to the fazenda." He took a piece of paper from his pocket and handed it to me. "Here's a map. It's easy to get there. It'll take you about a half-hour."

"What am I supposed to do?"

"She's pretty scared. I thought you could tell her you're a gringo too and explain why you're fighting with us."

"I don't think that's a good idea."

"Why not?"

"It'd be better if I'm Brazilian, so they can't trace me later."

Zeca thought a while, then said, "Maybe you're right," but he didn't sound convinced.

I felt sick, to tell the truth. I was thinking of how I could disguise myself. Zeca said there was a ski mask in the minivan that I should put on when I got to the fazenda. I could try to fake an accent. I even thought of disguising the fact that I'm black, but that was impossible. I mean I couldn't very well wear a jump suit and gloves when everyone else is walking around in shorts. She might think I was the invisible man and if I took off my clothes there wouldn't be anything there.

I drove to the fazenda that night after dropping Mireya off at school. It was one of those really huge properties full of cows and stuff and a house that Michael Jackson wouldn’t mind living in, the kind that generals somehow get to own despite their lousy salaries. I rang the bell and Socrates, the general's son, opened the door and gave me the thumbs-up sign.

"She's upstairs in the master bedroom," he said, and led the way up a curving staircase. I put the mask on, took a deep breath and went in.

She was propped up on the bed with her knees up reading a book by Stephen King. I could see a piece of her black panties that contrasted with the inside of her white thighs. She glanced over the book and said, "Don't you guys ever knock?" She straightened out her legs so the best part of the view was gone, but it was pretty good anyway. She was wearing a miniskirt and a tight sleeveless polo shirt without a bra so her nipples popped out like cherry pits. I went over to the bed and stood beside it. The room was big and bare. They'd removed everything that would have allowed her to identify the room.

"What do you want?" she asked nervously, despite the show of bravado.

"Don't worry," I said with a phony Brazilian accent. "Nobody's going to harm you."

"Fine, but I asked you what you want."

"I want to talk to you about ..er..certain things."

She looked at me kind of funny, like she noticed something about me.

"You're probably wondering why you're here."

"I'm here because you bastards kidnapped me."

"We didn't kidnap you, we just want to talk to you."

"What the difference?...Hey, are you a Brazilian, or what?"

"Yes, I am."

"How come you speak such good English then?"

"I lived in the States a while. Besides, lots of Brazilians speak good English."

"Not black Brazilians."

Bitch!

"How come that other creep said a gringo would come to see me then?"

"Well..er..they call me gringo because I lived in the States."

"Hmm. Hey, do you play chess?" she asked, trying to look through my mask.

"No. Black Brazilians don't play chess."

She smiled. "Ever been to Buenos Aires?"

So she recognized me despite the mask and the phony accent -- but could she be sure? I considered trying to bluff my way through but decided against it, because what if she told Zeca who I was, or who she thought I was. He'd laugh, but then he'd damn sure find out.

"OK Alice, just listen a minute. We're in this together and we gotta play it smart or we'll never get out alive." That impressed her all right; she stared at me with her mouth open. "These people think I'm an American preacher's son who lived in Brazil and learned the language and now I'm working in a favela because of my social conscience. They got this idea to kidnap you and they asked me to join them and I went along to make sure nothing happens to you."

"But what are you doing here?"

"I ran away from the embassy in Buenos Aires."

"What'd you run away for?" She was looking at me funny as though she didn't believe me up to then and was prepared not to believe what I would say to her last question.

"I just got fed up with all the diplomatic horseshit. You know what I mean."

"I do? Hey, why don't you take off that stupid mask? I know who you are anyway, Booker Tee."

I don't believe I mentioned yet that my real name is Booker T. Washington Smith. A psychologist would probably tell you that I didn't mention it till now because I don't like it, and he'd be right. I have absolutely nothing against Booker T. Washington; in fact I admire him. But that doesn't mean they have to name you after him. It's a pretentious name, another reason why I prefer Jackie Robinson.

"One of those guys could walk in any minute," I whispered. "And don't call me Booker Tee, for God's sake."

"What should I call you, Zorro?"

"Yeah, that's fine." I didn't mind that name at all.

"I'll turn off the light," Alice said. "Then nobody'll know if you're wearing the mask or not."

She switched off the night-table lamp before I could object. A slip of light rolled under the door from the hall outside and lamplight from the garden diffused itself through the closed shutters, but it was dark enough not to know whether I was wearing the ski-mask or not, so I took it off. I could see Alice's blonde hair and white skin though. She slid her ass over until she was sitting in front of me with her skirt pushed up to her hips from sliding like that. She took my hand and pulled me down beside her.

"Do they want money?"

"No, just publicity, then they'll let you go."

"I know you'll watch out for me, Book... Zorro." She giggled and let her head sink onto my shoulder and she put her hand on my naked thigh, just below the bottom of my shorts.

I was in love with Mireya, like I said, but as you probably know, adolescents are about the horniest toads around. I wasn't screwing Mireya because she was a minor, so when Alice, who was of age, started to fool around like that I got a hard-on that couldn't possibly stay inside my shorts, so I opened them and it jumped out like a rocket on its way to Mars. And when Alice went down on it I came in less time than it takes to say Booker T. Washington Smith. She went into the bathroom, to spit it out I guess, and when she came back she was naked and straddled me before my rocket collapsed. Since I had just come I was able to hold out indefinitely and we rolled around the bed in an orgy with Alice moaning "Again, Zorro, again, please!" and me trying to shut her up and liking it at the same time. It was obvious that she had a lot of experience with sex. It goes to show what an Ivy League education can do for you.

When I finally left the room and ran downstairs, Socrates asked me how it went and I said it went fine. "Does she really have a social conscience?" he asked.

I had forgotten all about that. "I think she may, but we've got to play it cool, not rush her." Socrates gave me the old thumb-up and I jumped into the minivan and somehow made it back to Mireya's school. She said she'd been worried about me, which made me feel like the turd I was.

"How did it go?" Zeca asked me in the office the next day.

"Pretty good, I think. I want her to trust me first of all and get to the serious stuff later."

"How much later?"

"Soon, maybe tonight if I think she's ready."

"As soon as possible, Jackie." He looked around, although we were the only ones in the room and the door squeaked like ten cats when someone opened it.

I had been thinking a lot about how to handle Alice. If I wanted her to come over to our side -- I know, I'm saying "our" side now, because that's the way it turned out -- the only way to do it was to keep on screwing her. I figured it was the only thing she gave a shit about, because she thought it was Love. But love is what I felt for Mireya, who I couldn't screw because she was too young and even if she weren't I'd have to go on screwing Alice in order to get her on our side. It's what my father would call a dilemma -- one of his favorite words.

The next night I started to talk to Alice about the condition of the poor in Brazil. "Do you realize that seventy per cent of the population is poor and half of them live in abject poverty?" (I modified Zeca's statistics a little because I figured they were exaggerated, though I didn't really know.) "The favelas are hotbeds of crime, perversion, drugs, violence. The children don't have a chance. They live on beans and rice and are undernourished, hardly go to school, are often sexually abused and the great majority of them become street children, first begging, then stealing, they become drug addicts and pushers, are often tortured and killed by the police. And do you know who's responsible?" Alice's eyes were saying: "What do I care, do it again, Zorro." So I did. She said she loved my brown skin, meaning she loved my black pecker.

"And you know who's responsible?" I repeated after an indecent interval.

"The government?"

"Not only. You and me and our fucking ambassador fathers who only protect American business interests. And the fucking capitalists, all of them, the American ones, the Brazilians, Germans, all of them." Boy, I was sounding like Zeca.

Suddenly, I mean suddenly, the door crashed open and there were about twenty Military Police in the room shouting and pointing their guns at us. Alice and I were still naked in bed. I sat up and she pulled the sheet over her head. They dragged me out of the bed and one of them punched me, breaking my nose. An officer screamed into his cellular phone that they'd found the American ambassador's daughter and her kidnapper.

"No, It's a mistake, I'm the--" I tried to talk spitting blood, but the soldier who punched me told me to shut up or he'd break my ass as well. So I shut up.

They took me to one of their interrogation rooms, still naked, and a fat guy said I should tell them who my accomplices were or he'd stick the red-hot poker he was holding up my ass. It was my nightmare come true.

"I'm the American ambassador to Argentina's son," I said in Portuguese with a phony American accent, trying to sound calm, although I was trembling like a guy who was about to have a red hot poker shoved up his ass.

The four goons in the room dropped their four imbecile jaws. Then the fat one began to laugh and his belly shook as he approached me with the poker reflected in his bloodshot eyes.

"Wait a minute!" The officer, who I hadn't noticed because he was behind me, came to the front and stared at me. He probably remembered that the previous ambassador to Brazil had been black. I don't think he believed me, but he wasn't taking any chances.

"Don't touch him," he said to the fat one, "at least not until I come back."

Fatso didn't like being deprived of his fun and he made a face, so the officer grabbed him by his shirt front and told him if he touched me he'd be boiled in his own fat. The officer was a little skinny guy, but it shows what authority can do.

It wasn't more than an hour, I guess, but it seemed a lot longer, when the officer returned with two Americans wearing pinstriped ties and short-sleeved shirts. One was a vice consul and the other didn't say who he was -- probably CIA. They questioned me and I gave all the right answers -- about who I was, not about the kidnapping. When they started on that I asked them what Alice told them and they said she was in shock. I told them to get me some clothes and get me out of that place. They borrowed a pair of shorts somehow and when we left I looked at Fatso and the one who broke my nose and said, in my best low Portuguese, "I'll remember you two pricks." Then we drove to the German hospital – the best in town -- where they fixed my nose, although I guess it'll always be crooked.

Luckily, Alice was in the same hospital. She didn't know what to say about the kidnapping and me so she had just kept her trap shut and they thought she was in shock. At first they didn't want to let me see her, but I said maybe I could help her so they let me. There was a doctor and a woman from the embassy present, not to mention Alice's mother, who was sitting in the corner looking like she just came out of a beauty parlor.

"Alice, darling, I think we have to tell the truth," I said, taking her hand. Things were pretty complicated for her. The Brazilian boyfriend turned out to be a famous soccer player, married to a movie star, a detail that Zeca had neglected to mention. When Alice disappeared in front of the theater the boyfriend decided to disappear too. Alice told me all that later.

"I mean that friend of mine, you know, Socrates? loaned us the house in the fazenda so we could be together for the week-end."

"Oh, Zorro, I'm so glad you're here," she cried and grabbed me around the neck and kissed me.

"Zorro!" her mother cried. "Who's Zorro?"

I was released the next morning when my father came and he shipped me off to a military school in Virginia where I did my senior high school year. It was a crock of shit, but I was an ambassador's son so no one bothered me much. I promised my father I'd stay if he agreed to let me go to the University of Sao Paulo -- finance me, that is, because I wouldn't be a minor by then. Finally he said OK, probably because USP is a lot cheaper that Georgetown or the Ivy League.

Once back in Brazil I made sure that Mireya finished high school and went to college. I also made sure that she stayed clear of kidnappings and that kind of stuff. There are other ways to change things, like what Dona Ute is doing. I made a list in my diary of all the things I like about Brazil. Most of them are predictable, like Mireya and Dona Ute and thumbs-up and the racial mixture and the mass that's better than a real one, and all the people walking around in shorts and smiling despite being so poor. I know it sounds crazy, but up near the top of the list, right below Mireya and Dona Ute, is one of the things I like most about Brazil: that they call me Jackie Robinson here.

After school I stayed in Brazil. My grandfather had become rich founding a recording company in Harlem that specialized in jazz and soul, and he left me a million dollars in his will. I had told him about the favela and how they called me Jackie Robinson and he wanted me to be able to stay here and help. So I did. Dona Ute began a school with a clinic in a favela in Rio and asked me to run it, together with Mireya.

Although Brazilians aren't interested in baseball, you can watch games on pay TV. So that's what Mireya and I were doing on Jackie Robinson Day. I tried to explain the game to her, but it wasn't easy. She knows my real name now of course, but still calls me Jackie.