Judith von Halle is mostly known for her books and lectures about the life and meaning of Jesus Christ. In this book she concentrates on a medical phenomenon which today has taken on the characteristics of a plague. Senility, involving short term memory loss and the general weakening of mental faculties associated with old age, has been known for centuries, but the illness we now call dementia or, in its more extreme stages, Alzheimer’s disease, has become more and more prevalent in modern society. Not only the aged are affected, but symptoms have been detected increasingly in the middle-aged, even in children. Before going further, it should be noted that there is a difference between “normal” old age forgetfulness and the illness which can lead to the affected persons becoming little more than living vegetables. The former is benign, the latter devastating.

In her introduction von Halle describes why she decided to expand the first edition of this book, which was directed to readers who were familiar with anthroposophy and its terminology. When she was invited to give a talk at a Swiss retirement home, where many of the listeners would have little or no familiarity with anthroposophy, she decided to first give a basic overview of anthroposophical concepts before going into the details concerning the nature and causes of dementia. After her talk, members of the audience, both those with no previous knowledge of anthroposophy and even anthroposophists, told her that the inclusion of her explanation of anthroposophical concepts made everything much clearer. So for the new edition she decided to include the explanation. I won't blame anyone for thinking that as the translator of the book I may be prejudiced. However, I can honestly say that one of the reasons for which I offered to translate it was the clarity and conciseness of this short explanation in the chapter What is the Human Being, which begins:

“...Such consciousness about the human being, his true inner and outer nature, can be acquired if one begins to consider him – which is, after all, his own being – with the methods of anthroposophical spiritual science. Practicing anthroposophical spiritual science is possible for everyone. No special qualifications are needed. By being human one is qualified. For it is not at all the task of anthroposophical spiritual science to investigate the spirit, but by means of the spirit to investigate the world and humanity. The fact that this spirit is available to the human being means that we are – without any kind of specialized training – very well equipped for anthroposophical investigative work, provided that we are really willing to do so.”

And ends with the paragraph:

“Given that man is a spiritual being with a physical body, it is obvious that the causes of an illness are not to be found in the physical context, but rather the physical breakdown is recognized as the impulse of spiritual causes and these causes are to be sought within the spiritual components of the human being.”

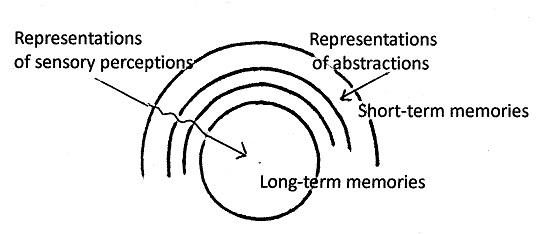

One of the first symptoms of dementia is memory loss. Von Halle goes on to describe how memory is a collection of remembrances and where and how they are collected in the human psyche, and once collected, or inscribed in the life-body, why it becomes more difficult, because of this illness, to retrieve them.

There are short-term and long-term remembrances. The author uses the image of a tree-trunk and its various layers to explain where they are stored:

Thus we can at least imagine why the different types of memories are on one hand more permanent and others less so, and on the other hand more – or less – , difficult to extract when desired. And how this affects people afflicted with dementia.

“That ever more people in western culture are stuck in the decay of their material nature is because they do not fill the gaps left by the physical decline in the fabric of their being with such spiritual thinking. This means that the decline of material nature – for example the dying of brain cells – would not necessarily be problematic provided that the human being has timely developed something capable of taking their place. This was the purpose of the Mystery of Golgotha, to bring the human being to a stage equal to that of the Resurrected One on Easter morning, namely to create an non-decomposable physical body through his I-forces, a no longer mineral-physical, but a spiritualized physical body."

Judith von Halle later describes the role the spiritual opposing forces play in the phenomenon of dementia. Lucifer strives to cause human beings to lose their footing on the earth, to “gawk at nirvana”, whereas Ahriman wants the opposite: materialism, the denial of the spiritual world and of the spirit in man. Therefore, she says, it is an error to think only in terms of good and evil, because Lucifer and Ahriman, spiritual beings themselves, are actually opposed to each other. The spiritual scenario is, in reality, a trinitarian one, with Christ in the middle opposing the evil on both sides.

This does not mean that the individuals suffering from dementia are necessarily materialists, or the opposite. Rather, dementia is a plague of humanity as a whole. But who has it and who doesn't isn't a roll of the dice either. The determining factor is karma.

“In general we can understand the outbreak of a certain illness in an individual as the expression of a karmic cause. From spiritual science we know that the disposition to the development of an illness reflects the result of certain behavior, of deeds in a previous life. Nevertheless, we should not ignore the fact that an illness is not sent by the opposing powers. It is we ourselves who really bring it about, but it is the good divine spirits who convert our karmic behavior in a previous life to a special “task” in the present life in order to give us the opportunity to grow by means of this task. The individual’s illness, whether it be the flu or a heart condition, is caused by his moral biography during the previous incarnation. So-called risk factors, which may really precede the illness, merely display the instruments, the “helpers” that cause the karmic illness to break out in this life, so that a healthy balance in the soul can be attained.”

However – and here's where it gets complicated:

“If we understand the illness of an individual as a karmic necessity, then the same illness in the many must be the result of a shared karmic necessity. It is then not a question of an individual destiny, but of a people’s or even humanity’s destiny, for the karma of humanity, which must be resolved, also exists.”

Therefore, dementia, when understood as a plague, may be related to individual karma as well as a shared human karma, also involving individuals whose previous personal karma is not the cause. This is also true in the case of natural disasters, tsunami and the like.

“The illnesses which the people of the west must increasingly fight against, and which are not of a karmic nature – at least not of an individual karmic nature – are directly related to the illness of the social organism, that is, to the unrealized spiritual and Christian-moral goals of today’s civilization.”

The author goes into considerable detail about the influences of individual and human karma. In respect to what is called above the “illness of the social organism”, she reminds us that dementia – “de-mens”, “without spirit” – describes precisely the current state of our western culture, and quotes Rudolf Steiner:

“Whoever sees through these things will of course not take them as a reason for opposing modern medicine with its external remedies. But a real improvement will never come about through these external methods. What will come about later always reveals itself in advance through esoteric knowledge. This consists of rightly perceiving how morality in the present can lead to better health in the future.”

If the human being is considered to possess only a physical nature, or when his spiritual components are ignored, and his illnesses are treated using physical diagnostic methods alone – changes in the brain's structure, for example – the spirit is unable to vivify the physical body, thereby maintaining or restoring its healthy stability, and only the symptoms are treated. By changing our conceptions of what the human being really is, however – that is, consisting of body, soul and spirit – real progress can be made in understanding an illness such as dementia, and illnesses in general. Judith von Halle concludes that this can be accomplished through anthroposophical spiritual science.

As far as Ahriman's role is concerned, she describes it as follows:

This process [the weakening of the human I] is Ahriman’s great plan, or that of even higher dark powers, to prevent the human being from envisioning the Christ-Being in the etheric world that surrounds and permeates our sensory world, and to utilize this envisioning as a foundation for spiritual and physical development. It is truly an anti-Christian struggle against humanity’s general awakening to living remembrance. In this way Ahriman tries with every means to take away man’s conscious control of his remembering process. He uses our comfortable materialistic thinking for this. But materialistic thinking is only the instrument for carrying out Ahriman’s plan to prevent humanity from achieving wholly conscious living remembrance, and he possesses an ice-cold, genial ability, added to the previously described processes which are responsible for the dementia phenomenon. They are all means helping to carry out this anti-Christian plan in the realm of matter, one coming from the spiritual world that works into the sensory world.

As a professional architect, Ms. Von Halle is well qualified to suggest what kind of surroundings are most useful in designing the living quarters for dementia afflicted patients in residential institutions. It is beyond the scope of this review to go into any detail here. She also indicates what kind of people should be entrusted with the patients' care:

“Caregivers would have to be found who consider it their life’s mission and their destiny’s vocation to be constantly together, at least during a part of their lives, with one, two or three dementia patients, and not as a passing fulfillment of duty in a stressful job. This can only happen out of real love, as a sacrifice not accompanied by inner discord. During the candidates’ interviews it would have to be decidedly emphasized that only people with this attitude be accepted in the assisted living plan.”

He or she would also have to be competent enough to carry out, or at least supervise, the artistic activities which Ms. Von Halle recommends.

All this, as the author admits, would be a difficult and expensive undertaking. Nevertheless, considering that the dementia afflicted are people who have been affected by life, who at the point in their lives when the strongest I-forces should have been developed, they have completely withdrawn, its seems to me that even the knowledge of such requirements can be helpful.

In concluding this review, it is, I think, appropriate to quote Judith von Halle's concluding paragraph:

Thus in a culture influenced by Ahriman, the Christian forces of compassion, endurance and love, although scarce, can be lighted anew, for it has been shown already how, in company with the dementia afflicted, these attributes of the caregiver lead to very beneficial effects – for the ill person as well as for the caregiver. This moral attitude would not only have a positive influence on the following generation and lead to a certain implicitness in care-giving work, but the prevalence of the illness itself would be limited from the outset by such a standard. Thus from an evil a good could arise – as in Mephistopheles’ motto in Goethe’s Faust: “I am a part of that force that always wants evil, and always creates the good.” – which can bring humanity a step further in its long and arduous path to becoming gods through the impulse of Christ.