She is not sure if she will be able to talk about everything again. "You know, it's exhausting," says Regina Steinitz in clear German during our first talk on the phone. When I call her the second time she says: "I was afraid you’d never call again." A few days later she opens the door to her apartment in the North of Tel Aviv in her pajamas. She has had a rest, she says, and goes back to the room where her bed and computer are - and her memories: Photos of her twin sister Ruth with whom she was hiding in Berlin,of her father who had to escape to America, from her husband Zvi who survived four concentration camps, from her Berlin girlfriends who were deported to Riga and Auschwitz, from her therapist Dr. Wilmersdorfer who helped her to fight her fear. All of them are dead except for her sister, but for Regina Steinitz these people are still alive. Here, in this room. She takes a seat on the edge of her bed, still in her pajamas, but very much awake.

You're sure this isn't too much for you?

No, no, I'm awake now. I just got a call from a friend who moved to America in Nineteen Hundred... What am I saying? I'm still in the 20th century.

Because you've lived in the 20th century for a long time.

Seventy years! I was born in the Charité [hospital] and grew up in Mitte [Berlin]. Our Jewish Mädchenschule was in Auguststrasse.

That’s where the restaurant Pauly Saal is today?

Yes, our school gym used to be there. It was a wonderful school. What I learned there, has remained with me to this day.

Where exactly did you live?

Auguststrasse 50b. The house burned down during the war, and for years there used to be a construction site there. I have good memory, also of how the State of Israel was founded, in 1948, when I was still in Berlin. There was a lot of joy amongst the liberated Jews. They drove through Berlin in open cars, with Israeli flags over the Kurfürstendamm. My sister was with them.

Israeli flags on Kurfürstendamm? How did the Berliners react?

The Berliners were cautious during Hitler and cautious after Hitler. You can't understand that if you haven't experienced it yourself. People had been living in a dictatorship for 15 years. When in 1938 the synagogues were burning, my brothers and I rescued books from the fire in the Ahawas-Scholaum Synagogue. We hid them in my father's darkroom.

Your father was a photographer. Is that the reason you have so many photos from the old days?

Yes, look! This is my father when he first visited us in Israel. He managed to escape to the United States in 1938. He wanted us to follow him later, but we never made it. My mother died of Tuberculosis, my twin sister and I were put in to the Jewish Children's Home in Fehrbelliner Straße. (She points to a photo on the wall where children sit around a table). That was at our last Hanukkah, at the next one everybody was dead except for Sylvia and me.

Is that the Sylvia Wagenberg about whom you write in your book that she had to deliver deportation letters to Jews?

Yes! Imagine that! She had a permit to ride the bus, even though she wore a Jewish star and Jews were forbidden to ride the bus. She had to hand out these letters for the Nazis, in which the people were told to get ready, someone would pick them up on Sunday or Monday. Of course Sylvia didn't know where they were going to be taken. When we heard that six million Jews were killed...

When and how did you hear about this?

After the war.

From whom?

Oh, such questions! You know, in Germany nobody spoke about these things. Soldiers came on holiday from Poland and were not allowed to say what they knew, but they sometimes told their wives about it. And their wives were not allowed to tell anyone else. That was the way it was back then. And after the war, everything was shoved under the carpet.

Did that make you angry?

I was angry that everyone said they knew nothing. Maybe they didn't know about Auschwitz. But Kristallnacht, everyone had witnessed, everyone knew about it. Or that the books were burned. And that the Jews were taken away! And that then their apartments were empty. And that people, whose houses had been bombed, moved into the Jewish apartments! There was still food on the table. Nobody knew that?! People always say there were only Nazis and Non-Nazis. What nonsense!

What was it really like?

People believed what the man said. He had a big mouth and he was screaming and promising, promising a lot. But the moment he came to power there was only violence, murder and killing. Jewish people were beaten on the street, men's beards were ripped off, and people didn't see that?

About 1,500 Jews survived in Berlin, more than anywhere else in Germany. You and your sister were among them. How were you able to do that?

You know, I once saw an interview with a lady who had survived a concentration camp. She said: "I died a hundred times and survived once." I wanted to climb into the TV and hug her. Survival did not depend on whether someone was strong or weak, intelligent or stupid. You can't imagine how many times one was close to death.

When you arrived at the detention center in Große Hamburger Straße, from where you were supposed to be deported to a concentration camp, did you know then how close to death you were?

No, I was a child, the same age as Anne Frank, 12 years old. We thought we were going to a Ghetto. Ghettos were known in Judaism, that had already happened. We were lucky. Ruth, my sister, wrote a letter to an uncle who wasn't a Jew, who got us out of the camp. It was the only reason we survived.

From then on, you lived with your uncle?

Yes, in Linienstrasse.

Did you have to hide yourself anyway?

Yes, of course. Not in a closet or anything. But almost always I stayed in the apartment, even during bomb alarms. The Gestapo had nothing better to do than look for Jews in the cellars as well.

Were you frightened?

No, no. I stood by the window on the fifth floor and watched the planes come in, Berlin lit up and the bombs fell. I was ready to give up my life, I didn't want to live anymore. I asked the good Lord to end the war, but my life was not important to me anymore.

Did you know that in Nazi Berlin there were so-called "Greifer", Jews who were forced by the Gestapo to hunt down other Jews?

Yes, I had heard of them.

Did you know Stella Goldschlag, the most notorious of the Greifers, who later took her own life?

No. It wasn't until after the war that I saw her on Oranienburger Strasse, at the Jewish Community. There was a book in which you could sign in if you had survived and were looking for relatives. I was looking for my brother who had been in Auschwitz. And there I witnessed how Stella came with her baby carriage. Apparently she didn't know that she was being searched for. People who had been deported to the camps because of her and who had just returned recognized her. I was just upstairs on the first floor when this happened, I heard the shouting and bent over the stairs. They took away her child and brought her to Nederschönhausen, to us.

To us?

In Niederschönhausen was the orphanage where I worked. Mr. Baruch gave me this job, a very nice elderly gentleman, a lawyer. I met him when I had to do labor in the war, cleaning toilets and offices in the Jewish community. He was sitting in an office, asked me if I wanted to type on a typewriter, he was like a father, and I longed for a father so much. After the war I met Mr. Baruch again. He asked me: How are you? And I was not well. He said: "You know what, we just got two houses back, one will be a home for the elderly, the other a children's home. The elderly home was meant for people who came back from Terezin. I have a lot of pictures of these people. What did I just wanted to say?

You wanted to speak about Stella Goldschlag's child.

Yes, Yvonnchen, she's still Yvonnchen to me. She was just a baby, and she was so cute. Mr. Baruch brought her to me in Niederschönhausen, but then, when the Wall was built, she was sent to the West, to foster parents, and these people didn't treat her well. She suffered a lot because her mother was considered the biggest criminal. No one else was responsible for everything. Such a poor girl!

She moved to Israel later, like you. Did you meet each other here again?

Yes, Mr. Baruch, who was still looking after Yvonnchen, wrote to me and told me to take care of her. Of course, I did. When I first met her, I tried to explain what had happened, that her mother had done bad things in order to save her own parents. I was in the detention center myself, I knew what it was like. But Yvonnchen didn't want to hear anything favourable about her mother. To her, her mother was a criminal. And indeed she was. But what else could she have done.

Thank God I've never been in a situation like this. A young man from Germany once told me he would have fought back during the Nazi era. I said to him: My darling, you would have joined in, you would have kept your mouth shut, too! That was a dictatorship!

Are you still in touch with Yvonne?

No, not anymore. I said: Yvonnchen, you're invited to my place. Warmly. You can always come, the door is open. She never came back. She was so traumatized by the people who turned her mother into the worst criminal.

Why did you decide to leave Germany for Israel?

I couldn't have lived in Germany any longer. Everything was so dishonest.

How was the arrival?

My brother, who had survived Auschwitz, put me in a kibbutz. That's where I met my husband. He was very quiet and lived in the room next to me. He had survived four concentration camps, two death marches and the Krakow Ghetto. His parents were murdered in the Belcec death camp. His father shouted: You murderers, you criminals! They shot him on the spot. Then his mother and brother were killed. I don't know how. I don't want to know, or it will haunt me again.

Have you ever received any therapeutic treatment?

Yeah, after I collapsed.

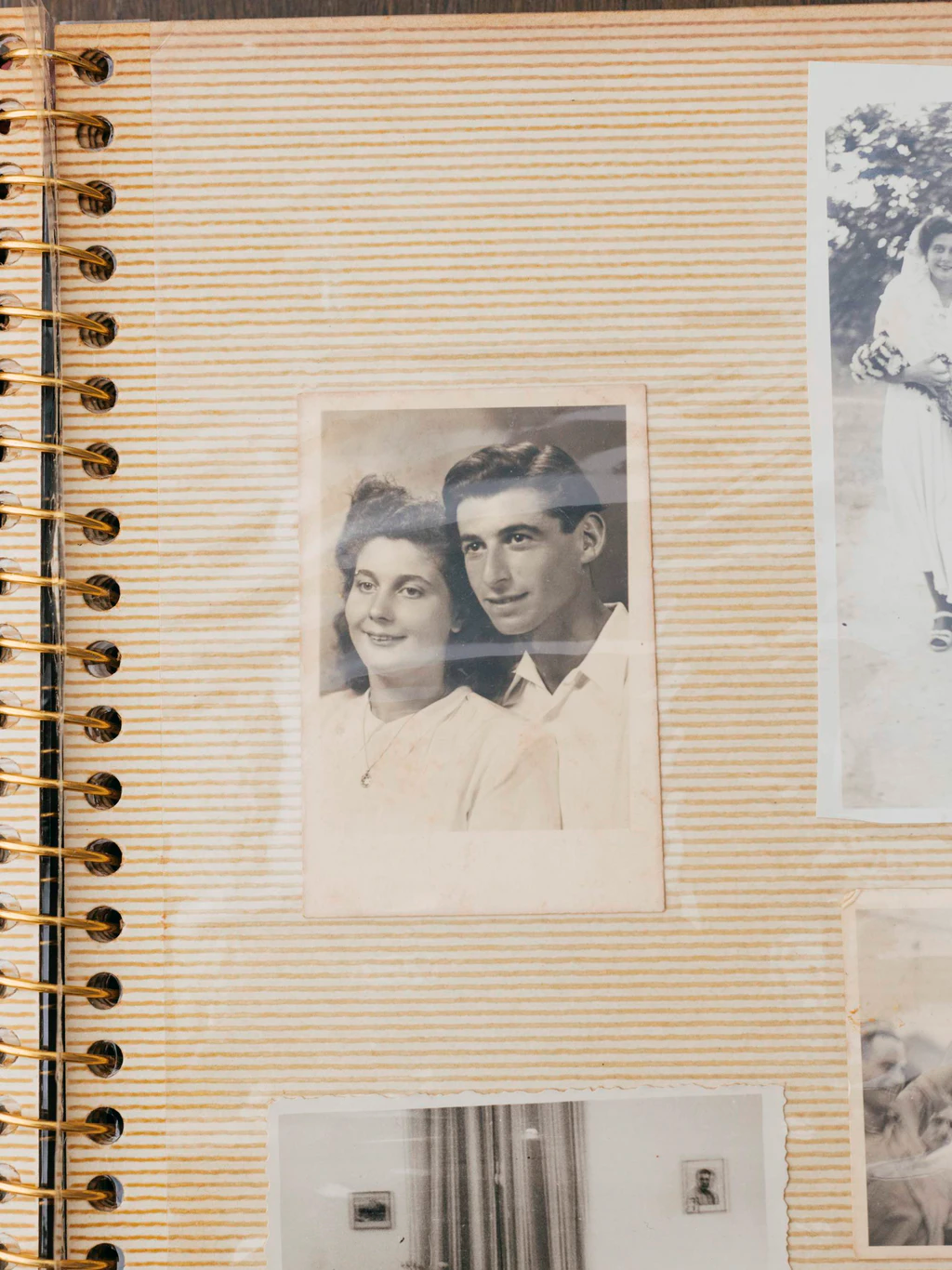

Regina Steinitz with her husband Zwi.

Photo: Jonas Opperskalski

When was that?

August 26, 1949. I was 18. My husband and I had just gotten married and were living in a small room. I was alone a lot, because my husband was busy from morning till night in the kibbutz. I calmed down and didn't understand what was going on with me. I couldn't bear to see anyone laughing anymore, couldn't eat anymore, felt nauseous, lost weight, didn't socialise with people anymore. Thank God my sister-in-law was a nurse in the kibbutz. She said, "Regina, I need to find you some treatment. That's how I ended up with the shrinks. Let me show you something, wait. (She gets up and takes a framed photo.) This is Dr. Wilmersdorfer, my psychotherapist.

She was German Jewish too?

Yes, a pediatrician actually. Here she is with my husband. Zvi was his Israeli name, his original name was Helmut. Dr. Wilmersdorfer always said: Regina, you mustn't say anything bad about Zvi! Oh, I miss him so much. He died this summer. We were married for 70 years.

For 70 years? How did you manage that?

My husband had lost everything, just like me, and started over again, just like me.

Did the therapy help?

It saved my life. In Germany after the war I was so busy, I worked as nurse in a children's home, finished school, went to the theatre, to the opera, to concerts. It was like a thrill. The doctors said that I only understood what I had lost after I experienced the silence here in the kibbutz, this completely ordinary life without the fear of being hunted. I also felt guilty that I had survived, that I could dance and sing. I was happy and sad, but I couldn't cry anymore. When the tears came back, I was the happiest person in the world. Since then I have been crying all the time.

Did you continue working with children here in Israel?

I got my diploma, became a head nurse in a health center and an instructor, I took care of pregnant women and their babies. Every child that opened its eyes was for me a child that came back from Auschwitz.

How are you feeling today when you are in Berlin?

It's not like I come to a foreign city, I have friends there and I still know every street. But it's difficult, especially in Berlin-Mitte. I cannot be there, I would never rent a hotel room there. I only stay there when I give a lecture, but certainly never for pleasure.

Is it because everything comes back to you?

Unbelievably back. You know what I mean? To me every corner is a place where something happened. Where stones were thrown, windows were smashed, where my schoolmate was picked up or my teacher. She was a doctor of literature, was expelled from university in 1933 and then taught at the Jewish Mädchenschule. Like our music teacher, who played Beethoven and Mozart for us. Ach, Kinder! These wonderful people wanted to make us happy. They're still inside me. I can't forget them. That's why I'm not doing well in Berlin. Once I had to vomit so badly that I had to go to hospital.

What happened?

I had just given a four-hour interview for the Foundation for the Murdered Jews in Europe and afterwards I had to go to the Jewish Children's Home where a TV crew was filming me. I walked through the rooms and was supposed to answer questions. They knew nothing, not a single name. They put pictures on the table and asked me: Who is this and who is that? All the children I had been there with. Then there was a lecture, and later a Dinner for survivors. Photographers were there. A member of the government was sitting next to me, I answered his questions. When the food came, my stomach started spinning. And then it happened. Zvi took me back to the hotel. At five in the morning I said to him: If I keep vomiting, I'll be dead soon. In the hospital I got infusions. They saved my life, but they didn't know why.

You did not tell them who you were and what had happened?

No, I couldn't speak at all. When that happened to me again on another trip, they prescribed medicine. It was the exact same symptoms I had when I collapsed in the kibbutz. When I go to Berlin now I always have a tablet against nausea in my pocket. My son says: Mama, you are allergic to Berlin.

Is it somehow comforting that you can share your memories with your twin sister?

I must say: Yes. Until today. Yesterday I was with her. She lives not far from here with a 97-year-old survivor from Lodz.

97? How do people who have been through so much manage to get so old? You are already 89 too.

I think it's because we had so much to catch up on, and that feeling never went away. I went back to school after the war because I did not want to do Hitler this favour, that I'm going to remain illiterate. My husband had to leave school when he was 13 and he still wrote five books and even translated them himself. We were always busy, kept on learning and working. You asked me earlier what the secret of my marriage was?

Yes, I did.

This marriage lasted so long because we both survived a very bad childhood and terrible things. We grew up as orphans, had the same mother tongue, education and culture. My husband was a hundred times smarter than me. A hundred times more human. A wonderful person. We could sing "Am Brunnen vor dem Tore" together, we sat together in front of our little radio and listened to concerts. And we built up the country together.

That's the secret of your marriage?

Yes, the Shoah kept us together. And the physical attraction too, of course. But that wouldn't have been enough to stay married for seventy years. We always did everything together. There was an incredible understanding between us. My husband would have encouraged me to give this interview too. He wanted me to tell how it was.