As lockdown restrictions begin to ease in England, we decide to go for our first pub lunch in four months to The Ram Inn, an historic 500-year old pub in Firle, East Sussex.

Firle is an attractive old village in the South Downs National Park, which manages to remain quite tranquil despite being just a few hundred yards off the ferociously busy main A27 road. It sits below the high chalk escarpment of the South Downs, from which one can see the English Channel in the distance. The road to Firle from the A27 leads nowhere except to the village and up to Firle Beacon on the downs, so there is no through traffic to disturb the peace; and since there is no street lighting, no traffic signs or road markings, and no modern buildings, one can easily imagine that the village looks very much the same as it did in 1911, when Virginia Woolf took a house there for about a year.

After a pleasant lunch in The Ram Inn and a welcome pint of Harvey’s Best Bitter for me, we walked around Firle, passing Virginia Woolf’s house. In a letter describing it to her future husband Leonard, she said: “This is not a cottage, but a hideous suburban villa – I have to prepare people for the shock”. With due apologies to the present occupant, she was not wrong, it is the ugliest house in Firle; nevertheless, she invited members of the Bloomsbury Group and other friends from literature and the arts to visit her there, including Roger Fry, Adrian Stephen, Lytton Strachey, Desmond McCarthy, Leonard Woolf, Katherine Mansfield, Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell.

We strolled on, pausing only to buy some quails’ eggs from a display outside a house, with an honesty box for payment, and then came to Firle Post Office and general stores, which according to a sign above the door was established in 1780.

A little further on, we came to a long path between beech hedges which brought us to the West Door of St Peter’s Church. The present church dates from the 12th century, though it is likely that there have been varying forms of religious settlement on the site since Druidic times.

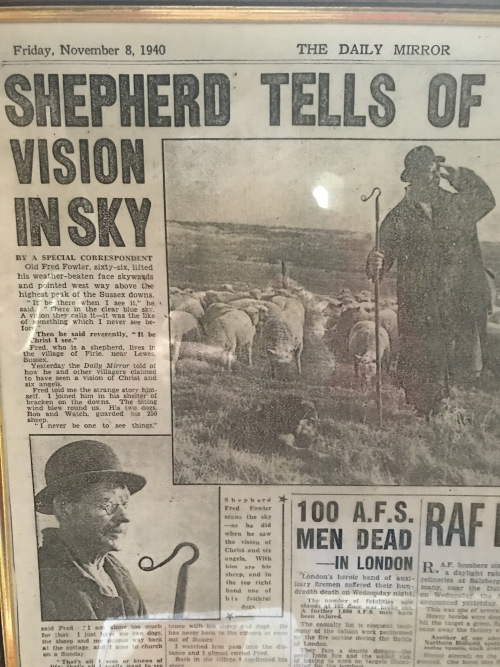

Inside the vestry, I am struck by a newspaper cutting displayed there, from the Daily Mirror of November 8th 1940, with the headline: “Shepherd Tells Of Vision In Sky”. The article, “by a Special Correspondent”, tells such an intriguing tale that I can’t resist quoting from it extensively:

“Old Fred Fowler, sixty-six, lifted his weather-beaten face skywards and pointed west way above the highest peak of the Sussex downs. ‘It be there when I see it,’ he said. ‘There in the clear blue sky. A vision they calls it – it was the like of something which I never see before’. Then he said reverently, ‘It be Christ I see.’

Fred, who is a shepherd, lives in the village of Firle, near Lewes, Sussex. Yesterday the Daily Mirror told of how he and other villagers claimed to have seen a vision of Christ and six angels.

Fred told me the strange story himself. I joined him in his shelter of bracken on the downs. The biting wind blew round us. His two dogs, Bob and Watch, guarded his 150 sheep.

‘I never be one to see things’, said Fred. ‘I am alone too much for that. (…) I’d just rounded up the flock that morning – it be about eleven. I says to meself it’s a nice clear day and I looks up west at the sky. Then I sees it. It be like what they tells me the cinema is like, but I thinks it be more real. There came a kind of panel across the sky’.

‘Inside the panel of white there was a cross, with Christ, his head to one side, nailed on to it. Round him were six angels. I counted ‘em, and they wore white cloudy robes to the feet. I know it was to the feet because I even saw their feet. I even saw their toes’.

‘When I got to the village I knew what I had seen was really there. There were other people who had seen it, too. But mine’s a simple life – I just have me two dogs, me sheep and me missus way back at the cottage and I come to church on a Sunday. That’s all I sees or knows of life; that’s all I really want to see or know’.

‘I forgot,’ he smiled. ‘There’s my pint I always have of a night’.

‘Sometimes though, if I think of it all now, the vision I mean, I wonders whether it really was Christ come to help put our world straight again’.

Old Fred walked away into the distance with his sheep and dogs. He has never been to the cinema or even out of Sussex. I watched him pass into the distance and I almost envied Fred.

Back in the village I confirmed his story. There were two sisters, widows, evacuated from London, Mrs Grace Evans and Mrs E M Steer who had seen the vision, and also a neighbour, Mrs Stevens. ‘Actually, we must have seen it a second or so before the shepherd did’, Mrs Evans told me, ‘because when I first looked into the sky it was clear blue. Gradually I saw the panel of kind of white cloud appear. I called my sister because it looked so pretty, then all at once we saw the crucifix and Christ. I saw every detail, to the nails in his crossed feet and the angels rose around him’.

‘One held a harp, another an old-fashioned pitcher with two handles. It was as clear as a picture and then, when I had got over my surprise, I called my neighbour to see the wonderful sight’.

‘Yes’, said Mrs Steer, it was so real it almost frightened me. I am not one to imagine things, and I used to smile at the story about the Angels of Mons – I always thought the soldiers who saw them imagined things, but now I can believe it’.

I called to see the vicar, the Reverend A G Gregor.

‘I saw nothing’, he said, ‘and I think the whole thing is nonsense’.

However, the vicar of Firle’s neighbour, the Reverend JR Lawson, the vicar of Glynde, said in an article published a week later in the newspaper:

‘I think those people who say they saw the vision were too much in earnest to be discredited. After all, our Christian religion is based on the vision of Bethlehem, which was only seen by a few. Therefore, why should not the story of apparently quite earnest people living today be equally believed? I certainly think the vision was seen and I only wish I had seen it myself’.

This is a lovely story and reminds me of The Shepherds’ Play from the Oberufer Christmas plays, not just because of shepherds and angels but because of the simple faith of Fred Fowler. A shepherd’s life consists of tending, watching, minding and guarding his flock, all of which can be summed up in one word: caring. The risen Christ said to Peter, “Feed my sheep”, but the Vicar of Firle’s brusque dismissal of the story sounds as though he was rather in the vein of St. Peter, who didn’t believe the tales of the women who had visited the tomb on the first Easter Day.

I should add that the present-day Vicar of Firle, the Reverend Peter Owen Jones, is a very different sort of person from the Reverend A G Gregor.

Firle has other Bloomsbury Group associations besides Virginia Woolf; Charleston Farmhouse, which was the home of several Group members, is just a short distance from Firle. In the churchyard at Firle are found the graves of Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, Angelica Garnett (the only child of Vanessa and Duncan), Quentin Bell (art historian, author and biographer of his aunt Virginia Woolf, and the second son of Vanessa Bell by her husband, Clive Bell) and Quentin’s wife Anne Olivier Bell, whose five-volume edition of the diaries of Virginia Woolf is a superb work of scholarship and elucidation.

When we get home, Sophia reminds me of an interesting coincidence: the date of Fred Fowler’s vision of Christ in 1940 is very close to the introduction of the ‘Big Ben Silent Minute’ on the BBC on November 10th 1940. The Silent Minute was an initiative of the adept Wellesley Tudor Pole, in which people in Britain and throughout the Commonwealth were asked to devote one minute of their time at 9.00pm each evening to pray for peace and thus create a channel between the visible and subtle realms through which divine help and inspiration could be received. The prime minister, Winston Churchill, and King George VI, offered their support and accepted Tudor Pole’s suggestion that it should coincide with the chiming of Big Ben in London. On Remembrance Sunday, November 10th, 1940, the BBC broadcast the chimes of Big Ben as a signal for the Silent Minute. This then continued throughout the war years and on up until the late 1950s.

Did the Silent Minute offer some kind of help against the Nazis, in a similar way that Fred Fowler imagined Christ coming “to help put our world straight again”? In a letter to President Roosevelt dated August 11th 1953, Tudor Pole said the following:

“At the end of the War a Staff Officer of the German Intelligence Corps made this remark when under interrogation at British H.Q. in Germany: ‘During the war you had a secret weapon for which we could find no counter-measure and which we did not understand, but it was very powerful. It was associated with the striking of Big Ben at 9pm each evening. I believe you called it the ‘Silent Minute’.”