“You know, you have the best hands in the world,” Matthew said, nuzzling her enticing bare shoulder lifting and moving rhythmically up and down, up and down, as she stroked the romantic high keys of the Chopin sonata she adored. After all, he thought, I’m an expert on the innate expertise of those hands. In a flash of libido he imagined his body stretched out along the keyboard and perceived her sensual touch as if on himself as she ran her long fingers with Calypso-like pink nails over the white keys and from time to time teased the blacks with furtive caresses. That wanton woman! She thrives on the suggestive with her sudden dips into the libertine. Matthew took her piano playing personally; he perceived her emphasis on Chopin’s high notes like an irrefutable invitation. Spontaneously, he accepted. And kissed her right ear tenderly.

“You should know,” she said, reacting to his ear kiss in what he considered her most sensual manner: her face flushed and with an audible little sigh she continued to tickle the keys while pressing her face hard against his. “And yours aren’t bad either,” she added in a hoarse voice. Though she was called petite, Laura was actually tallish for an Italian woman, slim and with the perfect female protrusions in all the right places, and, Matthew thought, she had the sexiest hands and legs south of the Alps.

“Just the way you react and say such things makes me … uh, makes me want to use the wide expanses of the top of this famous pianoforte for those things we appreciate.”

Physically, Matthew was nothing special, only slightly taller than his wife, neither slim nor robust, neither skinny nor muscular. But in Laura’s words his culo was classical. She said his derrière was much more beautiful than that of Michelangelo’s Davide sculpture which she dragged him to visit each time they were in Florence. All she had to do was say the word culo in her sinful way and his sham timidity vanished. Matthew and Laura spoke the same body language.

“I don’t get you,” Laura said, purposefully in her innocent mode. “What do you have in mind?”

“You know what I mean, dream lady. Us! On top of this would be Bösendorfer.”

“Matthew, your words are ab-so-lute-ly sacrilegious … what you have in mind doing on top of the world’s most sacred piano is ... is just obscene.” Obscene was another of her favorite words: pronounced by Laura it meant everything that was vaguely licentious and thus desirous.

“Pianos! The Bösendorfer! You never talk so sanctimoniously about the Davide sculpture, after all one of the world’s most admired works of art. But you speak of his ‘perfectly beautiful behind’ as if in a bordello. So it’s the Bösendorfer for us, Laura love.”

“Matthew!”

And so it went, their teasing, playfully debauched, love-filled vacation language in the shadow of the great Bösendorfer. Funny words were transformed into innuendo. Ordinary events became mysteries. Yet somehow the two-hundred and ninety centimeter long grand piano that had looked terrifyingly huge in the display room seemed to Matthew suspiciously small in the immense space of their vacation apartment ... and darker in color than he recalled. So either the leasing agency’s display room was too small and poorly illuminated to accommodate the Bösendorfer Imperial 290 or the agency had sent them a fake. Still, its identification was inscribed under the keyboard lid: Bösendorfer. And it did have those nine extra keys in the bass part, all colored black, as the leasor recalled so that pianists could play on it Bach’s works for the organ. Which was unimportant to them since Laura didn’t play Bach and Matthew couldn’t bear his organ stuff anyway. Odd though that Laura—who hadn’t insisted on a Bösendorfer—hadn’t noticed any disparities of color or sound. Why, she would’ve been just as happy with an upright. But he wanted for her the Bösendorfer 290, the king of pianos. Seemed proper for the 1920 atmosphere pervading Merano.

On the other hand she hadn’t seemed to notice the strangeness he’d perceived the moment they stepped into the luxury apartment they’d taken for the Merano summer season. Meran, former resort of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; Italianized Merano, summer-winter resort of its new state, Italy. Like stepping back in time, he felt, into a kind of twilight zone that in his ignorance about time he’d believed over and done. For different wars were today being fought and different plagues raping the land and people. Like a return to the future. For 1920 hung in the air, as if the Great War had just been fought and the Spanish flu was killing the last millions. And chic women were wearing Flapper cloche hats. Laura at the Bösendorfer seemed to symbolize the times.

Matthew saw mysteries everywhere. He was an investigator … of the unimportant, his wife teased. Not seeing the events happening in the period in which you live, he thought, was like trying to read a story but not reading the words written in the text. And odd things were happening here. Little things, but puzzling. Oh, those little things of life. Like the elevator that didn’t stop at the third floor. Bizarre. A real mystery. Nothing to do with 1920 but it reminded him of the time his magazine sent him to Moscow for a story and his hotel had no seventh floor. As if the architect had simply forgotten it. Local people later explained the situation: unmentionable people occupied that floor. Publicly it didn’t exist. But it did. And people knew. Now here in Merano there wasn’t even a number 3 button in the elevator for the floor that existed just under them; they could see the number 3 written on the door when they passed it several times a day. The third floor was there, the space was there … but no call button, no stop, no people. So did it really exist?

Or no less puzzling: the three tall dogs as if from other times and their little Terrier companion confined in the penthouse above them for at least twenty-two hours a day. Russian Borzois, he believed, and a short-haired Yorkshire terrier, canine prisoners that never but never made the slightest sound whatsoever in the apartment. No barks, growls, whimpers. Nothing. Sometimes he fantasized that they were not really dogs at all, but some otherworldly creature. Rare today Borzois were popular and chic in the 1920s art deco aesthetic. Still, the strangest of all, was that while he was so affected by mysterious events and people and objects, his wife never took notice of the inexplicable phenomena going on around them. Matthew, as insecure as he was curious, constantly felt a dizzying swirl of mystery rising in their lives, the objects that refused to remain inanimate, places and things coming and going, all the unknown factors uniting apparently intent on engulfing them in the web of the uncertainties of things and time that refused to remain constant.

When Laura asked why everything stirred such emotions in him, he blushed and said that he needed his emotions … just as much as they needed him. He later wondered why he said that. But no wonder, he thought. In the words of the poet Sharma the very search for a meaning in life is like discovering music in commotion or salt in the sand or water in parched land.

Their summer vacation this year of 2020 was exceptional. The whole 2020 was uncommon, sensations of the end of an epoch infecting the very air and making people in conservative Merano unusually carefree in the festive 1920 stage setting. In their reconstruct the Spanish flu had finally ended after its catastrophic passage through the world and Meran’s era of glory lived on. Back in the future of 2020 the statistical curve of the virus pandemic was beginning to descend farther south down the peninsula but the fever had never even begun in this Alpine resort. Here you felt apart from the main, truly an island, in a different world. People two hundred kilometers to the south were in quarantine while people of Merano were instead celebrating the centennial anniversary of Franz Kafka’s stay in their city from April to June of 1920. The twilight era of one hundred years ago relived. The whole year was marked by exhibits and lectures and organized visits to Kafka’s Meran, as the small Spa city in this ethnic German territory of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was called when Kafka lived here to heal his lungs. The acclaimed Meran air didn’t improve his health, Kafka later claimed, so he spent his time writing love letters to Milena Jesenskà in Vienna, letters destined to become his famous book, Letters To Milena.

This morning with such mysteries, suppositions and emotions stirring his psyche—if the psyche even exists, he thought—Matthew had been observing Laura at the putative Bösendorfer, marveling at the assuredness her upright figure exuded. Though her self-assurance underlined his lack of it, he nonetheless loved the way she sat at the piano, so straight, her posture perfect, and at the same time so relaxed and easy in her element, her light eyes now glistening in the rays of the mid-morning sunlight as the pink disk rose from behind the hovering mountains rising to the east. He contemplated those extra nine bass keys on this piano which the agency man had so vaunted. Laura never used them. Practically nobody does … except a few specialists who insist on playing Bach organ music on a Bösendorfer piano. Who in their right mind would want to be a specialist on Bach organ music for the piano? he wondered. Matthew disliked specialists intensely; his ideal was the Renaissance creator. Still, something in that piano was amiss; he would return to that agency and clarify the Bösendorfer affair.

While Laura played Chopin, Matthew pranced across the wide hardwood spaces to one of the great windows overlooking nature’s spectacle, that after two days he had come to love at any hour. On the one side lay wide green fields bordered by coniferous forests that continued to the foot of the mountain leading to the peak of the Kuhleiten they planned to climb. On the other side, a lake beyond which more mountains in the direction of Austria and his father’s Germany. They were surrounded by nature’s many manifestations. He was ruminating about the contrast between the outside world of nature and the pianos and art inside when he heard again the same brouhaha down in the gardens: first the furious barking and then the emergence of the three sleek tall dogs—most definitely Russian Borzois—followed by the short-haired Terrier, its short legs pumping to keep up with the others racing toward some obscure objective outside Matthew’s vision. Each time the doorman took them out, the same scene was repeated. Twice a day: the four dogs barking and yelping raced around blindly just to give vent to their wild nature totally pent-up all those hours in their penthouse penitentiary.

“You know, Laura, there’s something peculiar about this piano too,” he began, starting the trek back cross the room. Suddenly he stopped, turned toward the wall and said, “Ciao, Egon!” to the portrait of his favorite painter, Egon Schiele. Curious, he mused, that we have his portrait but not one of his works. Laura probably had it put there. How thoughtful of her. He touched it reverently, always saddened because he died so young … of the Spanish flu. Flu a century ago, flu-like Covid-19. He’d long wondered if Egon was madman or saint? Well, whatever, he was pure genius.

“So, Laura I’ve decided to write a story within the story, the story of this mysterious Bösendorfer. Of course my real story is about Kafka, seeing he’s what brought us here in the first place. Hmm! Well, I googled it, the Bösendorfer I mean, and learned a lot of interesting stuff. Things that make that so-called musical instrument agency in Bolzano look phony. Why, that may not be a real Bösendorfer at all. At least not one made by the Bösendorfer Klavierfabrik Gmbh in Vienna. Laura, this piano may just be dead wood, a beautiful piece of furniture but without anything super musical inside it. Without a soul. Yet, now that I think of it, this piano may have an evil soul: it may contain somewhere in its chords a complex surveillance instrument that intercepts top secret data of industrial espionage in our country and in Austria and Switzerland and Germany too. A four-country instrument. Only God knows the things they invent these days.”

“Oh, for heaven’s sake, Matthew! We just got here and you’re already off on another of your imaginative trips in that other world you live in ... always busy picking up the broken pieces of something or other.” Laura had observed her obsessed husband from the moment he’d arrived at the great window overlooking the fields and the forests and the mountains and stood there on purpose, she thought, flexing his beautiful derrière while he listened to the barking of the dogs, his head nodding as if in agreement with some crazy ideas churning in his mind. She knew he would re-tell his act of simply taking a look out the window as some great adventure over there on the other side of the immensity of this gigantic space, as he described the room.

Matthew said: “Well, my love, if you can tear yourself away from the Bösendorfer we can set out as planned on our Kafka in Meran Day. The sun is shining, the air fresh, and we’re in no rush. I thought a glance at the Grand Hotel Emma where Kafka only stayed a few days—too expensive for the poor sick man—before moving to the Pension Ottoburg where he wrote those amazing love letters. I’ll quote from some of them in my article. And on our way over to Lower Maia to see the Ottoburg we can walk along the Passirio River on the Passerpromenade as it’s called in German. I understand that the villa looks just as it did as a guest house … one hundred years ago, mind you.”

“Oh, per l’amor di Dio, Matthew, what are you smirking about?” Laura said, squirming around in the front row seat in the City Theater and again whispering that she couldn’t wait to get back to the piano. Some ideas had occurred to her while waiting for Professor Zecke to speak. “We’ve done everything according to what you keep calling our plan. I just wanted to play my piano. But no, I had to come with you on this Kafka chase. We saw the school that was once the Grand Hotel Emma… back in the Belle Epoch, all a century ago. we … ”

“Laura, my great love, we’re about to hear the Munich Professor Zecke speak of the greatest writer of that period, Franz Kafka.”

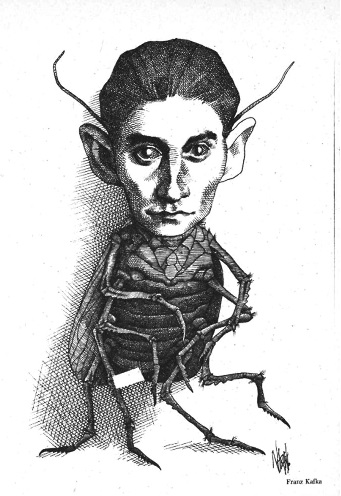

“And as you said registered at the hotel as ‘Herr Doktor Kafka, employee from Prague.’ Matthew, was Kafka not the one who became a bug and wrote a book about it?”

“Yes, Laura, The Metamorphosis. Die Verwandlung. His protagonist becomes a cockroach … by the way prompting the supposition that he was schizoid. Anyway Laura, you have to stop this! One sacrilege after the other. Please! You just never know about an artist. I read that effeminate Chopin hated people in general, but he still wrote beautiful music.” Matthew was struck by the capability of artists to adapt to the customs of those diverse peoples among whom they happen to live. Uncertain as to whether that mental characteristic merited reproach or praise, he thought it proof of the artist’s incredible flexibility and his thought so sensibly pure that he could forgive even evil when he sees its necessity or the impossibility of its elimination.

“Matthew, Tesoro, didn’t you say that this alleged professor’s name, Zecke, means ‘tick”. Oh Dio! So we’re here to listen to Doctor Tick speak about cockroaches.”

“Well, yes. But the subject of that novel is important, nothing to do with the meaning of names. You know, how in modern society we’re alienated one from the other… Alienation, Laura, a sign of the times.”

“Like you from me, eh? Still there seems to be too much ado here about insects. Well, I don’t speak the professor’s German and I’m alienated from the rest of you here ... even from you … you and your German father and German schools. But cockroaches? No, Matthew, this is just too much. Cockroaches!” she muttered, standing up noisily right under the nose of the startled speaker just as he stepped onto the stage. “See you later, alligator! You’ll find me at my Bösendorfer.”

There was nothing Kafkaesque about Herr Doktor Professor Mattäus Zecke. Much younger than Matthew had imagined him, Zecke was dressed in a dark brown cardigan and blue jeans, had long hair and a hippie look about him. Holding a microphone in one hand and sheets of notes in the other, he stood near the edge of the stage looking straight down at Matthew in front row center.

“Also, Meraner Freunde … So, Meran friends, Kafka specialists have long believed there is a missing Kafka letter … and that that letter is still somewhere here in the Meran where he spent his three sleepless months that we’re celebrating today … writing letters to Milena. But what letters!”

Aware that his opening was unusual, Zecke stopped, lowered the mic and looked down at Matthew as if waiting for his reaction. Matthew nodded knowingly and gazed back straight into the young professor’s eyes, somewhat surprised at his North German accent. He’d expected the young professor was from Munich like his own father. So that he would speak like local people here. But he sounded like a Berliner. So different from local Tyroleans. Different in mentality too. Zecke had just confirmed that peculiar things were indeed taking place here in the Alpine Meraner Luft. In the air of Meran. Much more than cloche hats.

“Well, Ladies and Gentlemen, I have found that missing letter!”

“What!” Matthew exclaimed, leaping to his feet, his phone, notebook and pen clattering on the hardwood floor just under Zecke’s eyes.

“Seems to run in the family,” the speaker said, leaning toward Mathew collecting his stuff while people in the front rows guffawed.

“Strange things are going on everywhere,” he answered, grinning sheepishly up at Zecke. “Just have to get used to them.”

After an embarrassed Matthew got re-settled in his seat, Zecke started over: “In 1920 Franz Kafka and Milena Jesenská began a love affair … at first through letters. Now you all know Kafka the great writer, but who was Milena? Well, Milena was a twenty-three year old journalist and aspiring writer and translator who lived in Vienna in a crumbling marriage. An astute young woman, she recognized Kafka’s genius long before others did. Despite the distance, despite the insurmountable blocks between German-writing Kafka in Prague and Czech-writing Milena in Vienna, the two developed an intense and intimate relationship. In their letters they literally stripped their bourgeois identities and bared their souls. The correspondence started when Milena wrote to Kafka asking for permission to translate his short story ‘The Stoker’ from German to Czech. That request quickly turned into a series of passionate and profound letters that Milena and Franz exchanged from March to December 1920. Kafka wrote daily, often several times a day. He told her to write every day too, even if just one word, ‘without which I would suffer terribly.’ He suffered on letterless days. Their letters are also linguistically interesting; Kafka wrote his letters in German—even though he was fluent in Czech—while Milena wrote in her Czech mother tongue.

“I think that at some point his soul began to suffer too. He wrote of his soul more than once. Now the soul was not a subject many critics have attributed to Kafka’s concerns. But some have. One day in June he asked Milena to react to his soul sickness. But got no answer. So he wrote another letter asking about the one dispatched the day before ... but the letter of the day before never arrived. It never arrived because it never left Meran. It has been here all these one hundred years.

“Kafka wrote Milena about his anxieties, fears, loneliness; his published letters reveal the extent of his anguish caused by Milena, the sleepless nights, and the futile situation of their love. Milena haunted his thoughts. She was his ‘savior’. Passionate, vivacious and courageous, Milena suffered greatly because of him, as Kafka said himself: Do you know, darling? When you became involved with others you quite possibly step down a level or two, but if you become involved with me, you will be throwing yourself into the abyss. She knew that herself, and yet she chose to sink because lust for life was part of her personality, and pain and rapture go hand in hand. Dostoyevsky was her favorite writer who confirms the propensity towards pain typical of Slavic women. The Slavic soul is a deep and dark place that one cannot wander into out of mere curiosity. Two such dark souls would have trouble living a simple life together. Their relationship was hot and cold; intense at one moment because their minds were alike, then alienated one from the other by distance. When she yearned to see him in Vienna, he was reluctant; when he wanted her to divorce her husband and come live with him, she wasn’t keen to do so.

“Yet though they were different in age and personality, no other woman entranced Kafka so much, and despite the abrupt end of their passionate correspondence I think Milena was just what he needed. Still, Kafka felt the age difference. He wrote:

It took some time before I finally understood why your last letter was so cheerful; I constantly forget the fact that you’re so young, maybe not even 25, maybe just 23. I am 37, almost 38, older by a whole short generation, almost white-haired from all the cold nights and headaches. He wrote: You see, the peaceful letters are the ones that make me happy.”

Zecke finally explained the missing letter. “I found it”, he said reaching into the pocket of his jeans, pulled out a pocket watch, “exactly ninety minutes ago. This is what happened: Kafka apparently gave his letter to Milena for posting to the concierge-handyman at the Ottoburg—the twenty-two year old already known as ‘Old Hansli’. But precisely that morning there was an unprecedented deluge in Meran. The waters of the Passer River rose, streets and houses were flooded. In short, Meraner Freunde, when many days later the rains finally ceased and the flood waters relented, the letter was forgotten. It was never mailed. Many years then passed. World War Two came and went. On his death in 1980, Hansli’s son Rainer, who’d worked his way up from chasseur to the concierge position at the prestigious Belle Epoque Hotel Europe Splendid, found the letter among his father’s papers in a basket in his attic. Unaware of its historical significance the today ninety-year old Rainer had left it in that same basket. I found it there!”

After Zecke finished speaking, Matthew hung around until the nimble professor jumped down from the stage where he stopped him. There was something fishy about the story of the letter. These Tyroleans like to play games. They love Bavarians of south Germany but Berliners are not among their favorites. Maybe Zecke hadn’t understood the ex-concierge. Or maybe the concierge was playing tricks on a gullible Prussian.

“I say, Zecke … uh, Professor, do you have a moment? I’m, er, a reporter, working on a story about Kafka in Meran.”

“A moment, yes. What can I do for you?”

“The letter of course. I would very much like to get a copy of it.”

“Well, you understand it is a great find for a scholar so …”

“Zecke, are you confident of the letter’s authenticity? Like the handwriting? Is it a real letter, properly dated as were all Kafka’s letters to Milena? And the envelope, is it, uh, of the period of one hundred years ago? You know, stuff like that.”

“Look, as I said, I just found it. But I will get experts to examine it and authenticate it. Certainly I don’t intend going down in literary history as the sponsor of a falsified letter of Franz Kafka.”

“Well, I think you should know that these Tyroleans like to joke around. Das Leben ist nur ein Scherz, they sing. Life is only a joke. And, well, if a Prussian is the butt of a Tyrolean game, then …”

“Oh, I’m not a Prussian. I’m just from the North … from a village between Hamburg and Berlin.”

“But didn’t you find it strange that a long lost letter from one of last century’s major writers was just lying there in a basket waiting for you … and after one hundred years and a world war and their land becoming Italian? Anyway, can I get a copy?”

“We’ll see. But only after I get back to Berlin and decide how to handle this delicate affair. Just leave your address with my secretary over there,” he said, pointing at a dark-haired young woman sitting on a straight chair facing the auditorium, her legs dangerously apart.

The concierge at the Hotel Splendid was honored to give the Herr Doktor Journalist, that is, Matthew, his predecessor’s address, a big house a few blocks away along the Passirio, the river’s Italianized name. Though Franz Thomas Rainer Müller—an important citizen of Merano—was named for Thomas Mann, Rainer Maria Rilke and Franz Kafka—all of whom former visitors to Meran—everybody called him Franzi. For effect, Matthew imitated his own father’s Munich accent to inquire about the lost Kafka letter.

“Ach, das war ja nur ein Scherz.” The ex-concierge snickered and slapped one hand into the other. “Just a joke and the Prussian fell for it. Ach, they’re so gullible! They once fell for a crazy stupid failure of a painter too.”

“Well, the Kafka letter is a pretty serious matter … for all of Meran.”

“And so was that mean Austrian … for the whole world.”

“Well, Franz Thomas Rainer, you’re a very perspicacious man, just as you should be with all those wonderful names!,” Matthew said in genuine admiration. “So okay, it was a joke on the Prussian. And a joke is a joke. Still, may I ask if you know anything about pianos. I saw a grand piano in the lobby of your former hotel. Quite beautiful.”

“Ja ja, I myself had it installed there years ago. My nephew rents pianos over in Bolzano. Oh, he told me he leased a Bösendorfer to some vacationer here.” The ex-concierge smiled his playful old man’s smile. “Is that vacationer you?”

“Ja, richtig, and my wife loves it. But you know, Franzi, there’s something funny about it. Don’t know what it is. That piano has nine extra keys. They’re colored black. But my wife never uses them. Chopin and all, you know. But I tried each of them out, just to hear the sound. Deep bass sounds. But one key, the one in the middle of the black nine, just goes ‘plunk’. No sound. Something strange about that piano, the Bösendorfer … the King of Pianos or not.”

Franzi was now all grins and snickers and slapping his hands on his legs as if to dance a Tyrolean Schuhplattler. “Ah ha, then maybe you know more than you think you know. Some things you just have to open up and take a good look inside. Like a surgeon does when he looks around inside an open stomach. Like when guests at my hotel were hospitalized—or even died—and we had to open their suitcases for some reason. Mein Herr, the things we found inside! Surprising finds. Everything from high-powered guns to manuscripts to enough barbiturates to kill a horse.”

Musing that concierges were among the best-informed people of the world, Matthew made his way back to their apartment. The bizarre atmosphere not only still reigned, it had intensified. But he couldn’t fathom why he felt that. On his approach through the condominium’s gardens, he stopped to watch the three tall Borzois and the little Terrier race past, their heads lifted toward the orange-colored heavens and the sun-lit mountains to the East and barking out of pure joy at their existence and their participation in the spectacle of nature around them. Where else in the world will I ever witness again such an extravaganza of the Earth, in this very moment threatened by mankind and defended only by its own eternal nature? With the dogs and the sunset in mind, on the elevator he hardly took notice of the absurd missing third floor.

He found Laura where she promised to be: at the Bösendorfer Imperial 290 and playing her beloved Chopin. She was wearing a cloche. Well, so that’s where we are, he thought. This bewildering story started in an unusual way just here at this piano that I always found strange, and now events, people, objects and history seem to be coming to a head in an unusual way, again at this Bösendorfer Imperial 290 … all happening according to the natural order of things. For a moment he admired his wife whose hands ran up and down the keyboard so freely, but his major attention was fixed on those nine darkened bass keys she ignored. The Bösendorfer itself occupied his inner vision and most of his conscious mind.

“Laura, my heartbeat,” he began absently, “did you know that a Bösendorfer piano was thrown off the Queen Elizabeth II into the ocean during the Falkland Islands conflict in 1982 to make room for helicopters.”

“For heaven’s sake, Matthew!”

“Just thought you’d like to know that,” he said vaguely, peering into the innards of the Bösendorfer as if into its very soul. Kafka thinking, he realized. And, for the first time he perceived this piano as a genuine Imperial 290. Peering into its secrets, he traced the chords into the dark left corner of the mammoth instrument … and there it was, just as Franzi the concierge had hinted: a tightly bound packet hidden by a piece of the spruce or beech or maple of the grand piano. Spontaneously he thrust his hand in and yanked the packet loose, and let out a whoop:

“Got it. Now Laura, try that fifth black key!

“Dong!”

“Again, Laura. Again!”

“Dong, dong, dong, dong, dong.”

“Now to read the real lost letter,” he said, his mounting excitement infecting also Laura. “Or is it like the piano a fake?” he said, his eyes fixed on Laura’s. “Somehow I’ve never believed the piano is a real Bösendorfer anyway.”

They opened the very slightly dusty package and there before them on the white and black keyboard lay a two-page letter. Immediately he checked the signature: Franz. The envelope was addressed to Frau Milena Jesenska. Matthew translated aloud the opening lines: “For one human being to love another,” Rainer Maria Rilke wrote, “is perhaps the most difficult of all our tasks… the work for which all other work is but preparation.”

In the second paragraph Kafka too turned to the soul: “The observer of the soul cannot penetrate into the soul, but there is doubtless a margin where he comes into contact with it. Recognition of this contact is the fact that even the soul does not know of itself. Hence it must remain unknown. That would be sad only if there were anything apart from the soul, but there is nothing else.”

“Laura, this doesn’t sound like the rest of his letters to Milena, he …”

“It doesn’t sound like the other letters because this was written by others, Matthew. And written recently. These scraps of beautiful paper, this whole thing is a forgery. How do I know? Open your mind and look closely at the paper and the matching envelope. Don’t you recognize it? This was not written one hundred years ago. Nor fifty years ago. Probably it was written recently. This is written on designer stationary, expensive, the kind used for luxury editions of important books. Look at the grain of the paper, the thickness, the weight. And see that tiny brown dot in the upper left corner? That’s the mark of the Cavallini Company. I think I still have some of the stationary at home. So now the number of false Kafka letters mounts. We now have two. How many do you think there can be?”

“Who knows, Laura, my treasure? But as they say in German, Life is only a joke. Das Leben ist nur ein Scherz.”