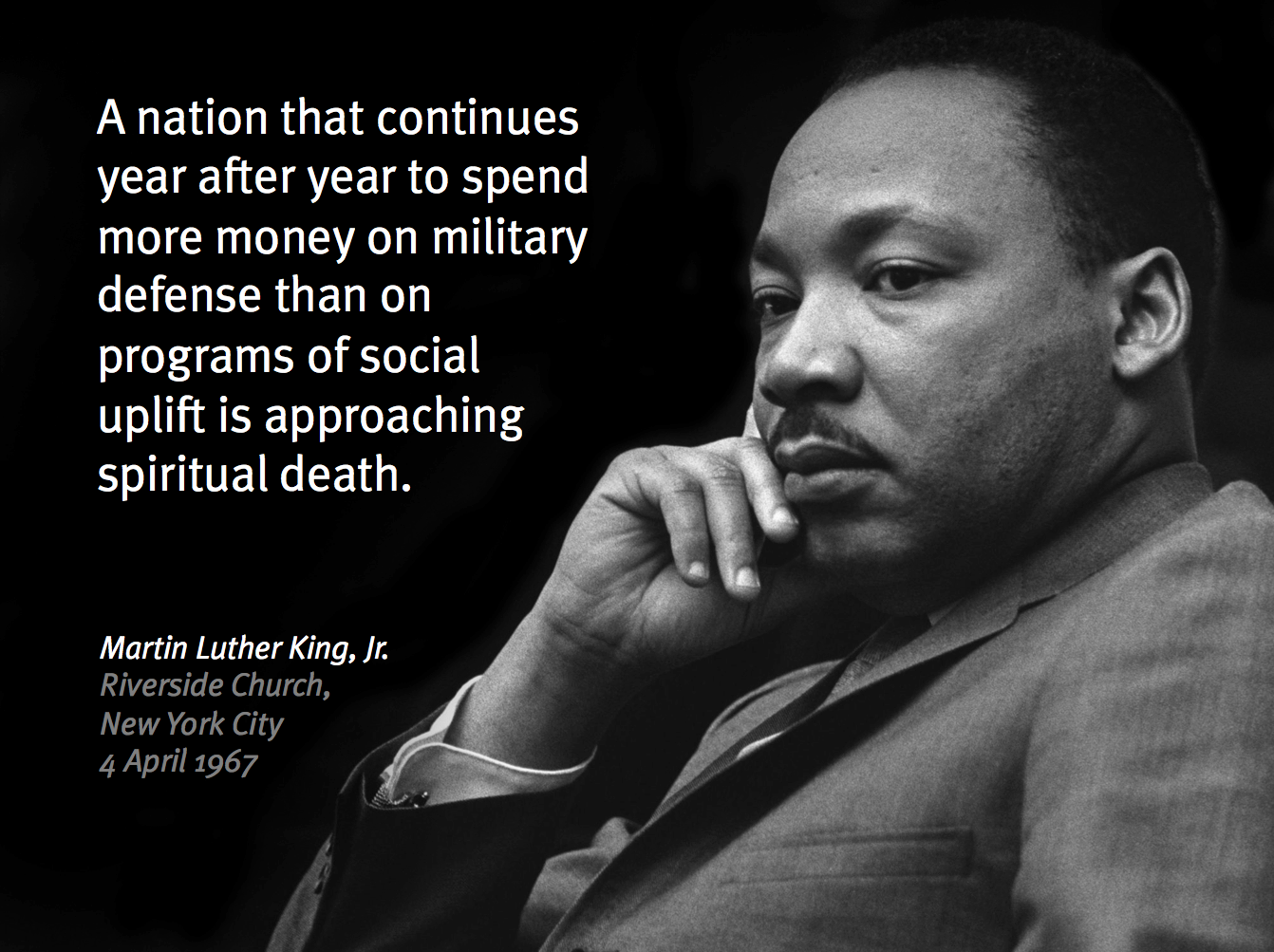

When Martin Luther King preached his famous sermon “Beyond Vietnam” at Riverside Church in New York City in April 1967, I don’t recall giving his words a second thought. Although at the time I was just up the Hudson River attending West Point, his call for a “radical revolution in values” did not resonate with me. By upbringing and given my status as a soldier-in-the-making, radical revolutions were not my thing. To grasp the profound significance of the “the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism” to which he called his listeners’ attention was beyond my intellectual capacity. I didn’t even try to unpack their meaning.

In that regard, the ensuing decades have filled a void in my education. I long ago concluded that Dr. King was then offering the essential interpretive key to understanding our contemporary American dilemma. The predicament in which we find ourselves today stems from our reluctance to admit to the crippling interaction among the components of the giant triplets he described in that speech. True, racism, extreme materialism, and militarism each deserve — and separately sometimes receive — condemnation. But it’s the way that the three of them sustain one another that accounts for our nation’s present parlous condition.

Let me suggest that King’s prescription remains as valid today as when he issued it more than half a century ago — hence, my excuse for returning to it so soon after citing it in a previous TomDispatch. Sadly, however, neither the American people nor the American ruling class seem any more inclined to take that prescription seriously today than I was in 1967. We persist in rejecting Dr. King’s message.

Martin Luther King is enshrined in American memory as a great civil rights leader and rightly so. Yet as his Riverside Church Address made plain, his life’s mission went far beyond fighting racial discrimination. His real purpose was to save America’s soul, a self-assigned mission that was either wildly presumptuous or deeply prophetic.

In either case, his Riverside Church presentation was not well received at the time. Even in quarters generally supportive of the civil rights movement, press criticism was widespread. King’s detractors chastised him for straying out of his lane. “To divert the energies of the civil rights movement to the Vietnam issue is both wasteful and self-defeating,” the New York Times insisted. Its editorial board assured their readers that racism and the ongoing war were distinct and unrelated: “Linking these hard, complex problems will lead not to solutions but to deeper confusion.” King needed to stick to race and let others more qualified tend to war.

The Washington Post agreed. King’s ill-timed and ill-tempered presentation had “diminished his usefulness to his cause, to his country, and to his people.” According to the Post’s editorial board, King had “done a grave injury to those who are his natural allies” and “an even greater injury to himself.” His reputation had suffered permanent damage. “Many who have listened to him with respect will never again accord him the same respect.”

Life magazine weighed in with its own editorial slap on the wrist. To suggest any connection between the war in Vietnam and the condition of Black citizens at home, according to Life, was little more than “demagogic slander.” The ongoing conflict in Southeast Asia had “nothing to do with the legitimate battle for equal rights here in America.”

How could King not have seen that? In retrospect, we may wonder how ostensibly sophisticated observers could have overlooked the connection between racism, war, and a perverse value system that obsessively elevated and celebrated the acquisition and consumption of mere things.

More Than the Sum of Its Parts

In recent months, more than a few stressed-out observers of the American scene have described 2020 as this nation’s Worst. Year. Ever. Only those with exceedingly short memories will buy such hyperbole.

As recently as the 1960s, dissent and disorder occurred on a far larger scale and a more sustained basis than anything that Americans have endured of late. No doubt Covid-19 and Donald Trump collaborated to make 2020 a year of genuine misery and death, with last month’s assault on the Capitol adding a disconcerting exclamation point to the nightmare.

But recall the headline events following King’s Riverside Church presentation. The year 1968 began with the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, which obliterated official claims that the United States was “winning” the war there. Next came North Korea’s audacious seizure of a U.S. Navy ship, the USS Pueblo, a national humiliation. Soon after, President Lyndon Johnson’s surprise decision not to run for reelection turned the race for the presidency upside down.

In April, an assassin murdered Dr. King, an event that triggered rioting on a scale dwarfing 2020’s disturbances in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Portland, Oregon, and Kenosha, Wisconsin. (Mere days after the assassination, as I arrived in Washington for — of all things — a rugby tournament, fires were still burning and the skies were still black with smoke.) That June, not five years after his brother was shot and killed, Senator Robert Kennedy, his effort to win the Democratic presidential nomination just then gaining momentum, fell to an assassin’s bullet, his death stunning the nation and the world. The chaotic and violent Democratic National Convention, held in Chicago that August and broadcast live, suggested that the country was on the verge of coming apart at the seams. By year’s end, Richard Nixon, back from the political wilderness, was preparing to assume the reins as president — a prospect that left intact the anger and division that had been accumulating over the preceding 12 months.

True enough, the total number of American deaths caused by Covid-19 in 2020 greatly exceeds those from a distant war and domestic violence in 1968. Even so — and even without the menacing presence of Donald Trump looming over the political scene — the stress to which the nation was subjected in 1968 was at least as great as what occurred last year.

The point of making such a been-there/done-that comparison is not to suggest that, with Trump exiled to Mar-a-Lago, Americans can finally begin to relax, counting on Joe Biden to “build back better” and restore a semblance of normalcy to the country. Rather the point is that the evils afflicting our nation are deep-seated, persistent, and lie beyond the power of any mere president to remedy.

America’s Twenty-First-Century Racist Wars

A devotion to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness defines the essence of the American way of life. So the Founders declared and so we are schooled to believe. Well, yes, replied Dr. King in 1967, but racism, materialism, and militarism have likewise woven themselves into the fabric of American life. As much as we may prefer to pretend otherwise, those giant triplets define who we are as much as Jefferson’s Declaration or the Framers’ Constitution do.

For various reasons, Donald Trump not least among them, racism today again ranks atop the hierarchy of issues commanding national attention. Political progressives, champions of diversity, cultural elites, and even multinational corporations attentive to the bottom line profess their commitment to ending racism (as they define it) finally and forever. Some not-trivial portion of the rest of the population — the white nationalists chanting “You will not replace us,” for example — hold to another view. The elimination of racism, assuming such a goal is even plausible, will surely entail a further protracted struggle.

By 1967, King had concluded that winning that fight required expanding the scope of analysis. Hence, the imperative of speaking out against the Vietnam War, which until that moment he had hesitated to do. For King, it had become “incandescently clear” that the ongoing war was poisoning “America’s soul.” Racism and war were intertwined. They fed upon one another.

By now, it should be incandescently clear that our own forever wars of the twenty-first century, fought on a distinctly lesser scale than Vietnam, though over an even longer period of time, have had a similar effect. The places that the United States bombs, invades, and/or occupies typically fall into the category of what President Trump once disparaged as “shithole countries.” The inhabitants tend to be impoverished, non-white, non-English speaking, and, by American standards, often not especially well-educated. They subscribe to customs and religious traditions that many Americans view as primitive if not altogether alien.

That the average G.I. should deem the lives of Afghans or Iraqis of lesser value than the life of an American may be regrettable, but given our history it can hardly be surprising. A persistent theme of American wars going back to the colonial era is that, once the shooting starts, difference signifies inferiority.

Although no high-ranking government official and no senior military officer will admit it, racism permeates our post-9/11 wars. And as is so often the case, poisons generated abroad have a curious knack for finding their way home.

With few exceptions, Americans prefer to ignore this reality. Implicit in the thank-you-for-your-service air kisses so regularly lofted toward the troops is an illusion that wartime service correlates with virtue, as if combat were a great builder of character. Last month’s assault on the Capitol should finally have made it impossible to sustain that illusion.

In fact, as a consequence of our post-9/11 “forever wars,” the virus of militarism has infected many quarters of American society, perhaps even more so in our day than in King’s. Among the evident results: the spread of racist and extreme right-wing ideologies within the ranks of the armed services; the conversion of police forces into quasi-military entities with a penchant for using excessive force against people of color; and the emergence of well-armed militia groups posing as “patriots” while conspiring to overturn the constitutional order.

It’s important, of course, not to paint such a picture with too broad a brush. Not every soldier is a neo-Nazi — not even close. Not every cop is a shoot-first, then-knock racist thug. Not every defender of the Second Amendment conspires to “stop the steal” and reinstall Donald Trump in the Oval Office. But bad soldiers, bad cops, and traitors who wrap themselves in the flag exist in disturbingly large numbers. Certainly, were he alive today, Martin Luther King would not flinch from pointing out that the American penchant for war in recent decades has yielded a host of perverse results here at home.

Then there’s King’s third triplet, hidden in plain sight: the “extreme materialism” of a people intent on satisfying appetites that are quite literally limitless in a society that has become ever more economically unequal. Americans have always been the people of more. Enough is never enough. True in 1776, this remains true today.

A nation in which “machines and computers, profit motives and property rights” take precedence over people, King warned in 1967, courts something akin to spiritual death. King’s primary concern was not the distribution of material wealth, but the obsessive importance attributed to accumulating and possessing it.

Embracing equity as a major theme, the Biden administration holds to a different view. Its stated aim is to enable the “underserved and left behind” to catch up, with priority attention given to “communities of color and other underserved Americans.” In short: more for some, but not for others.

Such an effort will inevitably produce a backlash. Given a culture that deems billionaires the ultimate fulfillment of the American dream, the only politically acceptable program is one that holds out the promise of more for all. Since its very first days, the purpose of the American Experiment has been to satisfy this demand for more, even if perpetuating that effort today inflicts untold damage on the natural environment.

Prophetic Deficit

In his Riverside Church sermon, King mused that “the world now demands a maturity of America that we may not be able to achieve.” In the decades since, has our nation “matured” in any meaningful sense? Or have the habits of consumption that defined our way of life in 1967 only become more entrenched, even as Information Age manipulations to which Americans willingly submit reinforce those habits further?

Maturity suggests wisdom and judgment. It implies experience put to good use. Does that describe the America of our time? Again, it’s important to avoid painting with too broad a brushstroke. But ours is a country in which 74 million Americans voted to give Donald Trump a second term, a larger total than any prior presidential candidate ever received. And ours is a country in which millions believe that a cabal of Satan-worshiping pedophiles controls the apparatus of government.

Whether wittingly or not, when Joe Biden committed himself in 2020 to saving “the soul of America,” he was echoing Martin Luther King in 1967. But saving the nation’s soul requires more than simply replacing Trump in the Oval Office, issuing a steady stream of executive orders, and reciting speeches off a teleprompter (something that Biden does with evident difficulty).

Saving that soul requires moral imagination, a quality not commonly found in American politics. George Washington probably possessed it. Abraham Lincoln surely did. For a brief moment when delivering his Farewell Address, President Dwight D. Eisenhower spoke in a prophetic voice. So, too, did Jimmy Carter in his widely derided but enduringly profound “Malaise Speech” of 1979. But as this mere handful of examples suggests, the rough and tumble of political life only rarely accommodates prophets.

While Joe Biden may be a decent enough fellow, at no point in his long but not especially distinguished political career has he ever been mistaken for possessing prophetic gifts. Much the same can be said about the highly credentialed political veterans with whom he has surrounded himself: Kamala Harris, Antony Blinken, Lloyd Austin, Jake Sullivan, Janet Yellen, and the rest. When it comes to diversity, they check all the necessary boxes. Yet none of them gives even the slightest indication of grasping the plight of a nation held in the grip of King’s giant triplets.

As a devout Christian and a preacher of surpassing eloquence, King knew that salvation begins with an admission of sinfulness, followed by repentance. Only then does redemption become a possibility.

Only by acknowledging the evil caused by the simultaneous presence of racism and materialism and militarism at the heart of this country will it be remotely possible for the United States to take even the first few halting steps toward redemption. We await the prophetic voice that will awaken the American people to this imperative.