There are men who thrive on the attack and retreat of the law-making process. I, on the other hand, would much rather tend my olive groves and leave the warfare over laws to those who enjoy it. But the law is the law. And when the Clerk of the Assembly came to me and told me it was my turn to serve on the Council, I did not welcome the news. Yes, I admire Solon and believe the reforms he gave us have made us a better people. And it is true that Tigani is not far away. I could spend a year on the council while keeping one eye on my business. But that is not my preference. Still, deep in my heart, I knew that the law that required me to serve was just. I would not walk away from my responsibility.

When I arrived in Tigani, I was hungry from the long walk. I went to the agora and soon found a stall where a man was selling dates. I headed toward it, but another man blocked my path.

“You are Thoth, yes?” he said.

“Yes. Who are you?”

“I wanted to talk to you about a law to be discussed in Council. You see, there have been problems lately with servants of some of our men of high standing.”

“You mean the slaves of wealthy men?”

He looked down and laughed dryly. “That’s such a harsh word,” he said.

“Harsh?” I said.

“They are parts of a complex arrangement we all live by. You know what I mean.”

“I wouldn’t pretend that I do.”

“Well, you know that men like Stelios hold servants, but that they also provide many of us with port services we all need. And, therefore, laws that affect him affect all of us, too.”

“Hmmm..., I suppose I see what you mean. But I just arrived and I’m very hungry. Can we talk after I’ve had something to eat?”

“I’ll only be a moment, I promise.”

“I’m sorry, Sir, but...”

“You must listen!” he insisted. “The law before the council would penalize men like Stelios, which would penalize all of us! They would be forced to spare any discipline toward their servants. And the man who most wants it to be passed is Pamphilos and he only wants it to pass because he has just built a new harbor and he wants to control all the merchant shipping himself. But Pamphilos holds great sway in the Assembly, so if it passes the Council and goes to Assembly, it will surely become law. It must be stopped in the Council! Of course, he will tell you that he has a better way because he does not hold servants. So, what difference does it make to him if servants cannot be disciplined?”

“I wouldn’t know.” I said. “But either way the vote goes, it’s really no concern of mine. I don’t use the port. I sell my olives here on Samos. And I don’t hold slaves.”

“But you must do what is right for all! Men like Stelios must be able to maintain discipline among their servants! Please think about what I’ve said.”

He walked toward the the council forum and I walked in the other direction toward the agora. The man selling dates was beginning to close his stall. I wanted to get to him quickly.

But then another man blocked my path.

“Excuse me, Sir,” he said, “I realize we don’t know one another, but I must talk to you.”

“Please,” I said, “I’m very hungry and the date merchant looks to be closing for the day.”

“I’ll only be a moment,” he said, taking my arm and pulling me aside. “There is something very important that I must talk to you about. I represent Pamphilos, who has just built a new harbor for shipping not far up the coast.”

“I see.”

“There is a law before the Council, one you must support. It makes it illegal for men like Stilios to beat, flog or in any other way mistreat their slaves. Our society is on the cusp of a new era, my friend. His tactics are a thing of the past and if we are to hold our heads up with the nations we trade with, then we must show that we are worthy of their respect and admiration. We cannot go on like barbarians! We must show the world a better way so that we will be the leaders of a world-wide community of traders and not some backward tribe.”

“So, I should support this law?”

“Indeed, you should. You must. The very future of Samos depends upon it.”

I looked toward the date merchant and saw that he had left.

“He’s gone now!” I said. “Do you know where I could get some dates?”

“I’m afraid not.” he said. “Perhaps there is a taverna nearby.”

“No, I can’t do that. I’m due at a meeting.”

“Sorry,” he said. “But I hope you’ll think about what I’ve said.”

I walked away scowling.

“Excuse me, Sir,” said a short man with an oddly twisted shoulder.

“I’m sorry, but I’m very hungry and I must find something to eat before my meeting.”

The man opened a bag he had slung over his shoulder, reached for some dates and put them in my hand. I devoured them in a moment.

“Thank you,” I said. “I’m sorry. What is your name?”

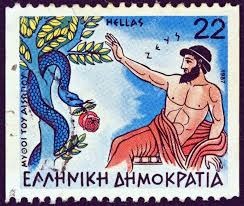

“I am Aesopos. I belong to Xanthus. I give him council.”

“Oh yes. I’ve heard of you. You have a lot to say for a slave.”

“Perhaps. But when all is said and done, I am still a slave. That’s why I must talk to you.”

“Well, you’ve fed me. I will listen to what you have to say.”

“Thank you.”

“I imagine you want to talk to me about the law coming before the council concerning the treatment of slaves. Well, I can see why you are concerned. This law will affect you, yes?”

“Xanthus treats me well for someone who owns my life. But the slaves under Stelios suffer greatly. They are beaten and held in chains. They cannot fight back. But the law before the council will protect all slaves from mistreatment by their masters. Pamphilos controls the assembly, so if it passes the council and goes to assembly, it will become law. But Stelios has been lobbying the councilmen with stories of how we will all suffer if slaves are treated humanely.”

“I have not decided how I will vote. I do not hold slaves. I do not use the ports that either Stelios or Pamphilos control. It won’t affect me.”

“But it does!” cried Aesopos. “Don’t you see? These are powerful men. Anything they do affects all of us. You, me, people we care about. Think of the frogs and the bulls.”

“What?”

“There was once a pair of frogs who shared a field with a pair of bulls. One day, the bulls got into a fight and stomped the ground flat. They kicked and bit one another until their rage took them over completely. They didn’t even see the frogs sitting near the pond. ‘We should get out of here!’ cried one of the frogs. ‘Oh, it’s their fight,’ said the other, ‘it doesn’t involve us.’ The other frog said, ‘It doesn’t matter whose fight it is. They’ll stomp on us before they even know we’re here!’ So, you see Sir, men in power fight and their fights affect all of us, simply because they are who they are.”

I looked into his eyes.

“We will all suffer or prosper because of the decision you make. Support this law because it is right, because you see it is right.”

He walked away and I stood by while his words took hold. He was not speaking for powerful men. He had no power of his own. And yet he made an argument I could not ignore.

It was another week before the law came up for debate. During that week, we discussed proposals, argued for and against positions and came to predictable conclusions. When the new law came up for debate, the air we all breathed immediately changed.

Stelios was the first to speak.

"My friends, I stand before you today as a man of business, like you. I speak of an issue that has far-reaching implications for all businesses. The proposal before us would prevent honest businessmen like me from enforcing discipline among our servants.

“Now, this may sound harmless enough. No one would ever choose to be flogged. It’s easy to see the appeal of such a law. But think for a moment about the effect this law would have. Without my servants, I cannot manage my port. If I cannot manage my port, you will all suffer. And if I and others like me cannot enforce proper discipline among our workers, we may not be able to keep the ports open. So, I say to you today, do not send the law to the Pamphilos’ Assembly. It is not in your best interest.”

I looked at Pamphlios after Stelios had finished. There was anger in his eyes, but he took back his composure when he came to the podium.

“My esteemed colleague believes very strongly in the rightness of his position,” said Pamphilos. “And perhaps he would be right if we were all businessmen and nothing else. But we are more than that. We are leaders. We are the guardians of our society, our way of life.”

“I suppose it’s up to you to decide what our society should be?” said Stelios.

“I could be the one. I or anyone here.”

“Yes, but we all know what you mean.”

“No, I don’t know what you mean. Why don’t you tell us?”

Some of the councilmen laughed.

“Who are you to be the judge of what our society should be?” said Stelios.

“As I said, anyone here can be a judge of what our society should be. But think of how we are seen by other nations we trade with. Do we want to continue to look like barbarians, not worthy of their respect?”

Then there was a wave of commotion through the crowd. I could hear debates breaking out around me. And then a strange thing happened. I stood up and motioned to speak. For a moment, I thought I was watching someone else. But there I was.

“The law before us is not a matter of business or of social order,” I said. “It is a matter of the people we are and, more importantly, what we should be, regardless of what others think of us.”

The crowd grew silent. Every face was looking into my face. Some looked at me with anger, others with bewilderment and still others with a fear of what I might say. But one or two looked at me with genuine curiosity.

“I have heard some men say that the law before us will protect workers we sorely need and raise our standing among other nations. I have heard others say it will erode discipline and make it impossible to keep order among the slaves. But let me ask you this. Have you ever seen a man beaten and put down by another man?”

I saw a few nods of assent.

“And have you ever been that man?”

No one said a word. But a few averted their eyes from mine.

“The law before us today prohibits the corporal punishment of slaves. I am not a slaveholder myself, but I am a citizen who wants a just society. You,” I said, pointing to one of the men who averted their eyes a moment before, “You have been beaten by someone, haven’t you.”

“Uh...no, never.” All the men around him laughed.

“You’ll find no one here who will admit to being bested by another man,” someone said.

“And why is that?” I said. “Perhaps it is because if a man can be oppressed by another man, he deserves to be oppressed?”

“And what if that is true?” someone said angrily. “I think whoever can be beaten down deserves to be beaten down.”

“Nonsense!” said someone else. “What have you shown yourself to be if you prey on the weak? What are we, wild animals or men?”

“Now listen,” I said with a force I didn’t know I possessed. "Any power you confer on any man can be used against you. If a slave can be beaten and abused, so can you be. Anyone can run afoul of someone in power. The only way that we can be free men is to make sure that no one has unbridled power over anyone.

“A thousand years ago, our ancestors were little more than barbarians. Today we live in a society where laws are made and respected. Our nation is like a child who has begun to mature. But we must keep growing, keep maturing. We must be better than we have been in the past. If we do not, then why should our nation survive? Passing this law would be a further step toward the maturing of our nation.”

I took my seat and the council remained silent. I wasn’t sure how my words fell on these men. The long silence made me a bit uneasy. But then the Council Chairman rose to speak.

“We have heard fine arguments for and against the proposal before us. Is there need for further discussion? Or shall we take a vote?”

The councilmen nodded as one. Each man rose in turn and passed the clay pot with his bean, casting each vote with an audible crack.

After all the votes were cast, we wandered around the agora while the clerk counted them. When he was finished, he motioned all of us back to our places to hear the results.

“Regarding the matter of the law introduced to prohibit the corporal punishment of slaves, the vote is fifty-seven for and forty-two against. The proposal will proceed to the Assembly.”

There was a bit of applause followed by stern silence. Aesopos looked at me and placed his right hand over his heart.

The rest of my time on the council was not nearly as eventful as those first days. But when my time was over, I looked back on it knowing I had done something I had never done before. I said my piece and moved others to do the same. I cannot say that it was the most important moment of my life. It is for those come after me judge. But for now, I see this as my greatest moment. There may be other great moments to come, perhaps even some that will surpass this one. But for now, I have this. And it is enough.