It happened once before, when I was a young man. The newspapers clamored for war, self-appointed know-it-alls told us why we had to fight and everyone believed them, especially the youngsters like me who got all fired up to join the army. So now, when those big headlines screamed ‘Remember The Maine,’ there wasn’t any more doubt that there would be war with Spain. And off they went to enlist, just like they were going to a picnic, as irreverent and ignorant as we were back in 1861. My eldest son told me he had to join up and I tried to discourage him. I told him how crazy it was for two groups of men to stand and blaze away at each other, but he wouldn’t listen. All he said was: "War’s not fought that way anymore, Pa ."

So I held my peace and watched him go, like my pa watched me go. When he died of yellow fever, before he even fought in a battle, it was another terrible affliction that I had to accept. But I guess he was right about it being a new kind of war, because it was over pretty quick and we got all these new places; Cuba, Puerto Rico, The Philippines and Guam. I never even heard of Guam. So I kept on farming and doing my chores but I was pretty much empty inside. I had been that way ever since the surrender at Appomattox, which ended my daily suffering, but left me a hollow man. I went through all the motions of the living and tried my best to be a good husband and father, and I never told anyone how I felt. How could anyone who hadn’t been there understand? Sometimes, when I went to town and saw the few old hands who survived the entire war, like me, there was nothing we could say. We just looked at each other for a moment, nodded in recognition that we were still alive and moved on.

Then one day, long after Spain surrendered, I saw a soldier who had just come home from the Philippines. I was buying something in Dahlgren’s general store and his pa brought him in. He had that look that I hadn’t seen since the war with the Yankees. His flesh was sagging on his bones and his uniform hung on him like a scarecrow on a hard luck farm. He walked as if it was a great effort to put one foot after the other. Old Mr. Dahlgren kept prodding him to tell us what it was like over there, but he refused to talk, until his pa urged him. Then he looked at everyone for a moment and said coldly: "You want to know what it was like? I’ll tell you. I watched my buddies die in ambushes, or of tropical diseases, or in battles with savages who just kept coming at us, even after we shot them. I watched my friends butcher women and children!" A look of absolute horror ate his face. "All I saw was death and suffering. Is that what you wanted to hear?" Then he turned and walked out. I couldn’t get him out of my mind the rest of the day.

That night I thought about the war with the Yankees, which I had shut out of my life a long time ago. I remembered how I had rushed to join up that spring of 1861. I ignored Pa when he told me not to go, just like my boy ignored me. Then Pa told me how bad it was when he fought the Mexicans in ’46, but I didn’t believe him. Everyone I knew was hurrying to the colors and I wasn’t about to be last. We were going to whip the Yankees good, then go back home with our chests full of medals. Once I was in uniform it didn’t take long for me to wake up. Almost half the boys I joined up with got killed or wounded in our first battle at Manassas. Maybe the Yankees finally ran off as fast as they could for Washington D.C., but not before they put up a mighty good fight. We fought up and down Virginia for the next two years and got leaner, hungrier, tireder and sicker. The more we ran out of ammunition, food, or shoes, the more the Yankees kept coming. We learned everything about the horror of soldiering the hard way.

One day we were camped somewhere near Chancellorsville, after a tough battle where we whipped the Yankees good. Of course it wasn’t like when the war first started. Then we knew we were better men then the city folk and immigrants they were going to send against us. Before First Manassas, most of us talked about beating them proper, then going home. If anyone thought it would go on and on for years, they didn’t say it where I heard. Anyhow, we had been resting because it had been a long, hard fight and these Yankees weren’t like the rabbits who used to run when they were beaten. When these Yankees lost, they retreated resentfully and we knew they’d be back. Then the word raced through the camp. Stonewall was dead. Rumors, like disease, travel swiftly in an army, especially when it’s bad news. This hit me and the old hands particularly hard, because we were the 31st Virginia and we were Stonewall’s men from the beginning.

We rushed to colonel Barstow’s tent, but he didn’t know any more than we did. Messengers kept arriving, each one with different news. The only thing they all agreed on was that Stonewall had been shot. The colonel finally got tired of our pushing and shoving at the messengers and he sent us back to our bivouac area. But he promised to let our company commander, lieutenant Rambeau, know as soon as he learned anything. We thanked the colonel, who was one of only three officers left in the regiment who had been with us from the start. All the others had been killed or invalided out. Colonel Barstow had started as a young lieutenant, full of fire and noble speeches. Now he was as old and tired as the rest of us. We snickered about lieutenant Rambeau as we walked. He was a moma’s boy, a blonde-haired stringbean with a mushy face that always looked ready to cry. He had reported to the regiment a few days ago, but he disappeared somehow before the fighting started. The joke going around the camp was who would shoot him first, us or them. Soldiers deserted other regiments before a fight, but not in the 31st Virginia.

We waited for news, but didn’t relax much. A couple of the younger boys babbled about beating the Yankees again, but the old hands quickly shut them up. By now we knew we could beat them and beat them, but they would still keep coming. We were sick, tired, cold and hungry and we didn’t have much hope left. The gossip around the campfire was no longer about victory. A few diehards still kept trying to convince the rest of us that massa Robert and ole Stonewall would find a way to defeat the Yankees. Most of us didn’t buy it. Now Stonewall was dead. One of the kids asked what would happen if General Lee got killed, but an old hand kicked him a few times and the kid slunk off, leaving the rest of us to brood about things. I couldn’t help thinking how lucky that kid was to get off so lightly. We had just lost our father and that dumb kid was talking about losing our grandfather. We didn’t need any more bad luck.

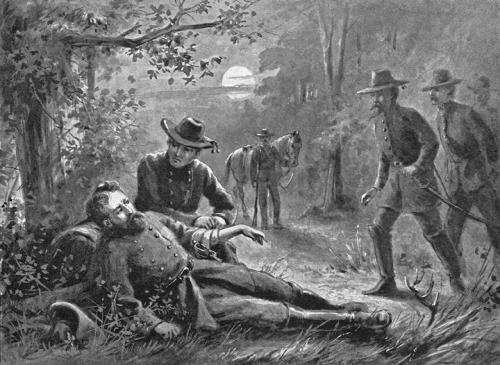

Later that night we found out that Stonewall wasn’t dead, he was just badly wounded. He had been returning from the battlefield in the dark and a nervous sentry, thinking he was a Yankee goblin or something, shot him. After two years of hurry up, then wait, it wasn’t a hardship to wait for news. We lost so many men at Chancellorsville that I guess they forgot about our regiment for a while, so we loafed in our tents. Once we packed up all the dead men’s belongings, they finally remembered us. They even gave us some food, probably pilfered from the Yankees endless supply of everything. Then the word flew around camp faster than wildfire. A new recruit named Billy Rawlins had shot Stonewall. They didn’t rightly know what to do with him, so they sent him home.

After Stonewall died, the war went on and on and the Yankees kept us on the run. When it was finally over, those of us who survived went back to our homes. I was one of the lucky ones. Pa had kept the farm going somehow, despite the voracious armies trampling back and forth across poor, battered Virginia. I had only been home for a couple of months when I heard that the man who shot Stonewall Jackson, Billy Rawlins, had hanged himself. It seems his pa kept telling him that he killed the man who could have won the war for the Confederacy. I guess the damned fool kid must have believed him, because he went into the barn, threw a rope over a beam and ended his life… But that was a long time ago.

I hadn’t thought about Billy Rawlins for many years. Seeing that soldier in Dahlgren’s store reminded me about what had eaten so much of my soul away. It all came back to me from a distance, like hearing a voice on that new telephone invention: the useless waste of young men, the suffering that devastated so many lives, the ease with which we forgot the dead. All I could think of was that if I knew then what I knew now, I could have gone to see Billy. I could have told him that what he did was just one more crazy mistake in a succession of terrible events. That Stonewall couldn’t have won the war. Hell, it was lost way before that. Only fools believed that we could win after the first year or so. The Yankees had everything. We only had pride and courage. Once they wore out our pride, courage just wasn’t enough. But my understanding of things came much too late to help poor Billy. I couldn’t help that trooper who lost his soul in the jungle. And I sure couldn’t help any of the other innocents who don’t start wars, only rush to fight them.