The three

jewels of Buddhism in relation to Anthroposophy.

by Bruce Kirchoff

����������� When

one listens carefully to what is said by Anthroposophists, one hears three

assumptions that play themselves out in many ways. These assumptions concern

the roles of teachers, teachings, and communities in the harmonious functioning

of the group of people following the teachings of Rudolf Steiner. Every

spiritual movement or religion has had to face similar challenges. We can gain

insight into how to cope with these assumptions through a study of how other

movements have dealt with them. The three jewels of Buddhism (Buddha, dharma, sangha) provide a particularly useful framework in which to explore

the roles of teachers, teachings, and communities in our spiritual striving.

����������� The first assumption that is common in Anthroposophy has two forms, an older and a newer. The older form states that that no one has attained higher knowledge following the path outlined by Steiner. My shorthand for this assumption is �There has been no attainment.� This assumption was particularly strong in the decades preceding the end of the millennium. As the millennium approached, it became increasingly difficult to maintain this assumption. It became clear that at least some people had attained something by following this path. At least some intercourse with the spiritual worlds was taking place. As this became increasingly apparent, the first form of the assumption began to wane, and a second form began to take its place. In this form, the assumption reads, �there is something to attain,� with the sub-text �we have not reached this attainment.� That is, though we begin to see signs of spiritual perception in our peers, we know that these perceptions are not the true perception of which Steiner speaks. We may have attained something, but it is not �the real thing.� This assumption assures us that we still have a long road to travel.

The second assumption is that the

teachings of Anthroposophy, as exemplified by the writings and lectures of

Rudolf Steiner, cannot be improved upon. We might say, �The teachings of

Anthroposophy are infallible.� According to this assumption, our task as

Anthroposophists is to understand and embody Steiner�s teachings. Our task is

not to contribute to them. This assumption tells us that we have nothing of

substance to contribute to these teachings, either through out own personal

experience or through out study of other spiritual movements. If we have

difficulty understanding Steiner, the fault lies with us, not with the

teachings, for his teachings are, in essence, perfect communications from the

spiritual worlds.

The third assumption is that

self-development is a matter for the individual alone. If one is to attain

�knowledge of the higher worlds,� to use Steiner�s phrase, then one must do so

on one�s own. Self-development is a matter for the individual, it is not a

community process. The community may be helpful in clarifying some concepts, in

sustaining a lending library, etc., but the role of the community is

supportive, it is not intrinsically involved in the process of

self-development. This is one of the most pervasive and least acknowledged assumptions

among Anthroposophists.

����������� We can

make the messages embodied in these assumptions more clear by looking at how

they are expressed in anthroposophical publications. Martin Barkhoff, writing

in Anthroposophy Worldwide, makes the two forms of the first assumption

beautifully clear.

As recently as November 1998 Professor Wolfgang Schad

said to me, �When you start to speak about your spiritual experiences in

anthroposophical circles, you get only two kinds of reactions. Either you are

considered to be no longer quite sound of mind or people say: �He seems to

think that he is Rudolf Steiner.��[1]

The response that the speaker is no longer of sound mind

is an expression of the first form of the assumption. Everyone knows that there

has been no attainment, so anyone claiming attainment must be slightly mad. The

second type of response, that �He seems to think that he is Rudolf Steiner�

exemplifies the second form of this assumption. The subtext of this response is

�and of course he is not Steiner. He has not attained the true spiritual sight

that Steiner speaks about.�

In the same issue, Suzanne Brodersen

speaks about the anthroposophical attitude to art, and addresses the second

common assumption: The teachings of Anthroposophy cannot be improved upon.

A matter that has always struck me is the attitude that

art done by anthroposophists is �better� that other art! This is perhaps not

intended, but somehow we must be aware of all the many others around the world

� not that we should make African or Eastern art ourselves � but we too easily

talk about art as if only �the German approach� is the right one![2]

The third assumption, that

self-development is only a matter for the individual, is so pervasive that it

is difficult to find anyone who expresses it. No one need express a �fact� that

everyone knows is true. Some of the most divisive assumptions work in this way,

as facts that everyone knows to be true. We will return to this assumption

below, in the context of Buddhism.

����������� If we

accept any of these assumptions and act on them as if they were true, our

progress toward the living knowledge of which Steiner speaks is blocked. To

understand why this is so, and to find a way out from the tyranny of these

assumptions, we will turn to Buddhism and some important things that we can

learn from Buddhist teachings.

Buddhism speaks of three jewels: the

Buddha, the dharma, and the sangha. Although there are precise

definitions for these terms in the Theravada[3]

tradition, they also have relevance to Anthroposophy under slightly wider

meanings. First, we will consider the meaning of these terms in Pali, the

language of the Buddhist texts, and then turn to their application to

Anthroposophy.

�Buddha� is a name given to someone

who discovers (or rediscovers) for himself the path of liberation (of dharma) after this path has been long

forgotten by the world. [4] Siddhattha

Gotama was the most recent Buddha, but a long line of Buddhas stretches into

the past, and perhaps into the future.

The term �sangha� has two meanings in Theravada Buddhism. The first meaning

denotes the community of monks and nuns that follow the Buddha. This is the

community of followers of the Buddha who have taken monastic vows. The second

meaning links the sangha to the

attainment of a stage of higher knowledge. According to this definition, the sangha is the followers of Buddha who

have attained the first transcendent path (sotapanna,

or �entry into the stream flowing inexorably to nirvana�) [5].

Both of these definitions are more restricted than how the term has been

applied in the West. In the West, the sangha

has come to mean the whole community of followers of the Buddha, not just those

who have taken monastic vows, or those who have attained a stage of higher

knowledge.� There is a Pali term that is

much closer to this western use of sangha,

though this term (parisa) is

virtually unknown in common parlance. Because of its common usage in the West,

I will use the term sangha in a broad

sense to mean the community of followers of the Buddha.

The word �dharma� has several meanings: (1) a phenomenon in and of itself;

(2) mental quality; (3) doctrine or teaching; (4) liberation (nirvana); (5) the principles of behavior

that a person should follow to fit into the natural order of things, or the

qualities of mind that they should develop so as to realize the �quality of the

mind� in and of itself; (6) when capitalized, any doctrine that teaches such

behavior or qualities.[6]

Clearly, the term dharma is very rich

in meanings, and deserves careful study. When we speak of the Dhamma of the Buddha, we refer to both

his teachings and to the direct experience of nirvana, the quality at which his

teachings aim.

In anthroposophical terms, we can

speak of these same three qualities as the attainment (Buddha), the teachings (dharma), and the community that supports

these two (sangha). Of these three

terms, �teachings� is probably farthest from the full meaning of its Pali

equivalent (dharma). We can partially

correct this problem by expanding on the idea of teaching by considering three

other closely related Pali terms, pariyatti,

patipatti, and pativedha.

Pariyatti

refers to theoretical understanding that is obtained through reading and study.

This is the business of most anthroposophical study groups and branches. Their

aim is to build an understanding of Anthroposophy through study of Rudolf

Steiner�s books and lectures. This aspect of practice may merely lead to an

intellectual understanding of Anthroposophy, or it may be a stepping-stone to

experience. As Steiner emphasizes in Theosophy

and How to Know Higher Worlds, study

of the ideas of Spiritual Science can be the first step in higher knowledge.

. . . the exercises described here should be accompanied

by the intensive study of what researchers in spiritual science bring into the

world. Such study is part of the preparatory work in all schools of esoteric

training. . . . reading

such writings and listening to the teachings of esoteric researchers are

themselves a means of achieving knowledge for ourselves.[7]

�If our knowledge stops with intellectual understanding, we have

remained at the stage of pariyatti,

but if we have used our study to begin to traverse the path to higher

knowledge, we have begun patipatti (practice).

Patipatti is the practice of the

teachings (the dharma) that we learn

about through study. For many anthroposophists, patipatti will be a form of meditation, though artistic activity,

work in service of others, and even the experiences of everyday life can be a

form of practice if we approach them with the proper attitude.[8]

Practice, in this sense, is the vehicle that bridges the gap between

intellectual understanding (pariyatti)

and direct, first-hand realization (pativedha).[9]

Pativedha (realization) is the

highest of the three aspects of the teachings (dharma) because it is based in experience. As we approach the

threshold of the spiritual world and become aware of our non-sensory

experience, we are at the stage of pativedha.

The practice of Anthroposophy that

culminates in direct experience is supported by the community of people who

share the same path (the sangha). The

common assumption that individuals can enter the spiritual worlds alone, cannot

be supported either from a study of Buddhism, or from a study of Steiner�s

writings and lectures. Certainly, spiritual sight depends on the desire and

ability of the aspirant to purify him or herself. However, it is not true that

success depends only on the individual. The community of people who follow the

same path (the sangha) plays an

essential role in supporting this striving. In Buddhism, the fact that practice

and attainment is supported by a community is recognized by giving the sangha a place as one of the three

jewels.

To help us understand how and why a

community is necessary for attainment

of spiritual sight we can turn to the Steiner�s own biography. The community in

question can be small, but it must exist for progress to occur. We see this

fact in Steiner�s life, in his meetings with the herb dryer Felix Koguzki and

the person Steiner refers to as �another personality� to whom Felix introduced

him. Though there were undoubtedly others who helped Steiner along his path, we

know relatively little of the effect that these people had on him.[10]

Our knowledge of Felix and the �other

personality� comes from a remarkable lecture Steiner gave in Berlin, February

4, 1913.[11]

The occasion of this lecture was an assertion made by Mrs. Annie Besant, the

President of the Theosophical Society, that Steiner had received training as a

Jesuit. Steiner felt it essential to refute this assertion for several reasons.

Up through 1912 Steiner had been the General Secretary of the German Section of

the Theosophical Society, and was in some ways subordinate to Mrs. Besant. The

relationship between Steiner and the other leaders of the Theosophical Society

had been strained since 1907, when the German Section of the Society hosted the

biannual congress and introduced innovations that did not please members from other

countries.[12] The rift

grew over the next few years, with Mrs. Besant and her colleagues preparing for

the incarnation of the new �world teacher,� who would be a reincarnation of

Christ.[13]

Steiner strongly disagreed with the assertion that Christ would reincarnate,

and lectured widely on Christianity in an attempt to show the true meaning of

the incarnation. The final break with the Theosophical Society came in early

1913, when Mrs. Besant wrote an official letter intimating that Steiner was no

longer the head of the German Section.[14]

Finally, the charge that Steiner had received Jesuit training, and even that he

had been ordained as a priest, had been published in several Jesuit books and

magazines for some years. Although he had attempted to set the record straight,

the false rumors persisted. Now that they were being promulgated by Mrs.

Besant, Steiner felt that he must speak openly about the course of his life.

His lecture of February 4 gives us one of the few glimpses of his personal life

and relationships in the years before he assumed the leadership of the German

Section of the Theosophical Society (1902). In this context, Steiner speaks of

two people who served the important function of providing a community in which

he could develop his spiritual sight.

�. . . Felix was the

herald, as it were, of another personality, who served as a means to stimulate

in the soul of the boy [Rudolf Steiner] - who indeed already lived in the

spiritual worlds - the regular, systematic qualities one has to have in order

to gain knowledge in the spiritual worlds. . . . he used the works of Fichte,

connecting them with certain studies that gave rise to things in which it is

really possible to find the seeds of his occult science. . . As a starting-point, he often used a book that had

frequently been suppressed in Austria owing to its anticlerical tendency, a

book that could stimulate one to follow special spiritual paths and steps.[15]�

The importance of this

small community cannot be overemphasized. In addition to specific training,

Felix and the �other personality� provided a sense of companionship, and

confirmed the spiritual sight that Steiner had possessed all of his life.

Without this training and confirmation it is doubtful that Steiner would have

developed his spiritual sight to the degree that he did. Steiner's own words

clearly imply this. He speaks of gaining�

"the regular, systematic qualities one has to have in order to gain

knowledge in the spiritual worlds."

It is important to note

that the community to which the young Rudolf Steiner was introduced included

more than just Felix and the "other personality." The lessons Steiner

received were delivered via the works of Fichte, and "a book that had

frequently been suppressed in Austria owing to its anticlerical tendency." An occult study of Fichte

strengthened Steiner�s connection to European intellectual life. This

intellectual milieu provided a community that was extremely important in

shaping Steiner�s approach to the spirit.[16]

In addition to deepening of

his spiritual sight, it is likely that the training offered by this "other

personality� served to introduce Steiner to his higher ego. In the same

lecture, Steiner says of the paths and steps that he was led to follow �These

particular streams that pass through the occult world, which can be recognized

only if one bears in mind a double stream moving forward and backward, appeared

in a living way before the boy�s soul.[17]�

To understand what he means by this sentence, we need to turn to another of his

writings. In the final chapter of How to

Know Higher Worlds, Steiner makes it clear that the stream from the future

bears the Greater Guardian of the Threshold, an aspect of our higher ego.[18]

By combining these two sources we can see that Steiner is telling us, without

explicitly saying so, that his meeting with the "other personality"

was an initiation experience for him. He met his higher self through this

experience. This meeting is a deeply personal and significant experience. It is

important to realize that Steiner did not come to it alone. He had support form

a community, all-be-it a small one, in the form of Felix, the "other

personality," Fichte, and the "anticlerical book." It is easy

for us to neglect this community and discount its effect on Steiner, but these

influences were essential. Without them, the Rudolf Steiner we know would not

have existed. Without Felix, Steiner�s initiation into the higher worlds would

have come in a quite different way, with who knows what results.

We are all dependent on these

types of communities. We undertake self-development as members of a community,

or we do not undertake it at all. The fact that the sangha is one of the three jewels of Buddhism helps us recognize

the important role that the community plays in our spiritual development.

Without a sangha, there can be no spiritual

attainment, but it is also true that without attainment, the sangha has no reason to exist. The three

jewels are intimately linked. If the Buddha had never lived, or had never

attained liberation, there would be no reason for a community to form around

him. This community initially consisted of the five monks with whom he

practiced austerities. These monks, and others who joined them, accepted his

teachings and became the vehicle for their promulgation in the world. As the

first Buddhist sangha, they heard and

recorded his sermons, and advanced their own development in the process. These

sermons are now preserved as part of the Pali canon of Theravada Buddhism. Not

only did the sangha provide a vehicle

for the liberation of its members, but it also was the vehicle for the

publication and dissemination of the texts. Without the sangha there would be no Buddhist teachings today. This is true

both with respect to recording the teachings, and with respect to their

genesis.

During the Buddha�s life,

the existence of the sangha was an

important cause of the Buddha sermons. If there had been no one to receive

them, it is highly unlikely that he would have spoken as he did. If no one ever

stopped to listen, his sermons would soon have ended. After his death, the sangha was the vehicle for the

continuation of his teachings. His work had to be carried by others, or it

would have died with him. The sangha

is thus necessary for both the origin and the continuation of the teachings.

The relationship between

the attainment (Buddha) and the teachings (dharma)

is also intimate. The Buddha�s teachings spring from his attainment. He himself

makes this clear in his first sermon.

"And, monks, as long as this knowledge & vision of mine -- with its three rounds & twelve permutations concerning these four noble truths as they actually are present -- was not pure, I did not claim to have directly awakened to the right self-awakening . . . But as soon as this knowledge & vision of mine -- with its three rounds & twelve permutations concerning these four noble truths as they actually are present -- was truly pure, then I did claim to have directly awakened to the right self-awakening. . . Knowledge & vision arose in me: 'Unprovoked is my release.[19]�

����������� Without attainment, there would be no teachings, but the

relationship between attainment and the teachings goes deeper than this. Once

the teachings have been given, they must be kept alive. Teachings that exist

only as texts that are never read, or that are read but not understood, are not

true teachings. To be living, the teachings must be understood. This requires

some degree of attainment. In Buddhism, this relationship is demonstrated from

the very beginning. When the Buddha finished his first sermon, the monk

Konda��a attained the first stage of awakening, and thus gave birth to the ariya sangha (noble sangha).[20]

His attainment shows that the teachings are living realities.

����������� After the Buddha�s death, attainment continues to play a

role in Buddhist teachings. Without the level of understanding that comes from

direct experience, the Buddha�s sermons would soon pass into obscurity. They

would be texts that had no meaning. No one would be affected by them. To be

affected by them means to have understood them (pariyatti). To have understood them, means to have worked with them

(patipatti). To have worked with them

leads to direct experience (pativedha).

If it does not, the teachings are dead. One could even say that are no longer

true. It is not that the words on the page have become lies. It is that what is

written no longer has any connection with experience. To return the teachings

to a state where they can be understood requires some level of attainment. This

attainment need not be at the same level that produced the teachings. We do not

all have to become Buddhas. However, it must be of the same nature as the

original attainment. Subsequent attainment must be implicitly the same as the

attainment that produced the teachings. We might say that it is qualitatively

the same, but quantitatively different.

����������� If the teachings fail, if they begin to die, then the

community (sangha) must fail too, and

with it the attainment that should follow from the teachings. A living

community has living teachings at its center. These teachings are still

attached to the master who produced them, but have also been enlarged and made

relevant to current conditions. If the teachings do not have this character,

the community forms around a center that is irrelevant to its members. Attempts

to follow the teachings then lead to frustration, and most likely to

self-flagellation, for the purity of the teachings will seldom be questioned.

Failure to attain the promised insights will be blamed on the individual, whose

ability or dedication to the cause will come into question. The community that

should provide support for its members will now turn on itself, and begin the

slow process of disintegration.

����������� When this happens, when the community fails, there is no

longer any support for attainment. It would be as if, following the Buddha�s

sermon, Konda��a had

gotten up, yawned and said �How boring! I think I will go bathe.� If the

teachings are not seen as relevant, there can be no community, no group of

people who support each other in their striving and attainment. Without the

community, attainment fails. Without attainment, the teachings are not

understood and cannot be kept alive. Without living teachings, the community

fails. Instead of a positive, mutually reinforcing set of interactions, a

vicious circle ensues. The jewels of Buddhism must shine together, or none can

shine at all.

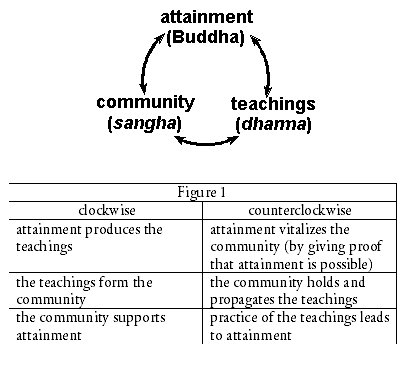

����������� The

relationships between the three jewels can be summarized in a diagram (Figure

1). This relationship is intimate and profound. Each jewel is dependent on the

others in order to function properly.

����������� Let us now return to the three assumption found among

anthroposophists and investigate their relationship to the three jewels. The

assumption that there has been no attainment is a failure of the Buddha. The

assumption that the teachings cannot be improved upon is a failure of the dharma. Finally, the assumption that the

anthroposophical community has no significant role in the attainment of

spiritual sight is a failure of the sangha.

When one of these jewels fails, they all fail. Where does this leave us, and

how do we get out?

����������� In one of his final lectures before passing, Schmidt-Brabant

summarized the situation in many groups following Steiner�s teachings today.[21]

At the end of August [1923], shortly before the Christmas Conference, Rudolf Steiner spoke of �walls of occult imprisonment.� The symptoms described can be recognized today when an individual or a group can no longer act in the world freely. When all endeavors are thrown back; when we seem to be stuck. Then there are the walls between each other � when we see people doing marvelous work but they cannot come together. We have the experience of sitting in a group � all the right things are said, but at the end nothing happens. We go our own way feeling frustrated, as if something comes between people to hinder.[22]

To find a way out of this prison

we can turn again to Buddhism, though this time to Tibetan Buddhism. The

American Buddhist nun Pema Ch`dron speaks of three

qualities which we already possess, and which we can ripen and mature. These

are the qualities of precision, gentleness, and letting go. The cultivation of

these qualities can help us restore the jewels, and find a way out of the

occult prison.

When the Buddha taught, he

didn�t say that we were bad people or that there was some sin that we had

committed � original or otherwise � that made us more ignorant than clear, more

harsh than gentle, more closed than open. He taught that there is a kind of

innocent misunderstanding that we all share, something that can be turned

around, corrected, and seen through, as if we were in a dark room and someone

showed us where the light switch was. It isn�t a sin that we are in the dark

room. It�s just an innocent situation, but how fortunate that someone shows us

where the light switch is. It brightens up our life considerably. We can start

to read books, to see one another�s faces, to discover the colors of the walls,

to enjoy the little animals that creep in and out of the room.

In the same way, if we see

our so-called limitations with clarity, precision, gentleness, good

heartedness, and kindness and, having seen them fully, then let go, open

further, we begin to find that our world is more vast and more refreshing and

fascinating than we had realized before. In other words, the key to feeling

more whole and less shut off and shut down is to be able to see clearly who we

are and what we�re doing.[23]

How do we apply these

qualities?

Precision always involves

a clear recognition of what is seen. When we become aware of an assumption,

precision allows us to see not only the assumption, but also the fact that we hold it. When we become aware of the

assumption that there has been no attainment, and are precise about this

awareness, we realize �Ah! I think that

there has been no attainment.� This recognition that �I think� the assumption allows us to take a

step away from the it, and to begin to see that the assumption is not something

that must be true. The assumption is

merely something that �I think.� The possibility that we are wrong now opens

up. As this happens, we may find ourselves shifting from the older form of this

assumption (there has been no attainment) to the newer (there is something to

attain that we have not attained). Being precise allows us to question even

this. We begin to wonder about the thought that there is something to attain, something

that eludes us. In becoming curios about this thought, we are already applying

the second quality: gentleness.

The innocent mistake that

keeps us caught in our own particular style of ignorance, unkindness, and

shut-downness is that we are never encouraged to see clearly what is, with

gentleness. Instead, there is a kind of basic misunderstanding that we should

try to improve ourselves, that we should try to get away from painful things,

and that if we could just learn how to get away from the painful things, than

we would be happy. That is the innocent, na�ve misunderstanding that we all

share, which keeps us unhappy.[24]

Through gentleness, we

learn to question our assumptions without being harsh with ourselves. It is

very easy to turn our precision on ourselves and feel that we are defective

because we have assumptions. Gentleness toward ourselves prevents this. It

allows us to open up, to step away from our assumptions into a world whose

boundaries have not been explored. As we gently explore the assumption that

there is something to attain, we begin to open to the possibility that we do

not have to work at attainment, that we do not have to improve ourselves, that

we are perfect just as we are. This realization can free us to work

productively on ourselves. Instead of trying to attain something that we know

(i.e., assume) will take many lifetimes, we can work knowing that what we are

doing at this moment is already perfect. When we accept this, we begin to open

ourselves to the stream of time that flows to us from the future. This stream

carries our higher self to us. This self has already attained all that we

desire now. From our perspective, this attainment exists in the future, but

from the perspective of that future, we are the goal of its striving. Our

higher self flows toward us. If we assume that it cannot reach us, that there

can be no true attainment for us in the present, then we interfere with its

approach. But if we accept that we are already perfect, then the future comes

to meet us, and we are perfect. We

create the conditions under which the future can come to us. From the

perspective of the reverse stream of time, the future has already happened. We

only have to realize that this is so to make it real in our lives.

Through precision and

gentleness, we learn to let go of our assumptions. Letting go is the third

quality that we can ripen, but it is not something we do actively. Letting go

is something that happens when we apply precision, with gentleness. We do not have

to �let go,� it is not an activity that we can control or manipulate. It is

more like grace. It depends on our receptivity, but it comes on its own, in its

own time. Letting go allows us to open wider, to take in more of life, to

accept pleasure and pain with the same welcoming spirit. To say yes, to

whatever life bring us.

We can apply these same

qualities to the second assumption found among anthroposophists: the teachings

of Anthroposophy cannot be improved upon. First, there is precision; there is

the recognition that something is wrong. We notice, with Suzanne Brodersen,

that anthroposophists think that their path is better than everyone else�s.

Because we are being precise, we notice what this recognition does to us. It

causes us to feel inwardly tense, to be critical of anthroposophists as well as

of other spiritual streams, and to pull slightly away from all of them. We

become more isolated and critical. Then, because we have chosen to be gentle

with ourselves, we ask with great gentleness �What is that about? What is it

about that we feel critical and isolated? Where does this come from?� We start

to develop a great curiosity about ourselves. Our gentleness towards ourselves

transforms our thoughts and feelings into amazing jewels that we marvel over,

and wonder about. �Where do they come from? Isn�t that one interesting?! What

fascinating things lurk inside of me.� We do not need to answer these

questions. If we merely� hold them with

gentleness, we find that we begin to let go of the assumption we previously

carried. The assumptions begin to dissolve on their own. We do not need to work

at this. It just happens as a result of our gentleness. Now, because we have

fewer assumptions, we become genuinely curious about what others think. We

might ask Suzanne Brodersen why she thinks as she does. We might ask her why

she thinks that anthroposophists should not �make African or Eastern art

ourselves.� We might begin to find links between Anthroposophy and

non-anthroposophical art. We might write an article on these links. In short,

we begin to say �and� instead of �but� when confronted with teachings that are

not presently in the anthroposophical canon. We begin to enlarge the canon, to

contribute to and improve the teachings, to make them relevant to the world

situation today. The thought that Anthroposophy has any fixed teachings is now

far behind us, for we are creating those teachings as we learn. The teachings

have come to life for us.

The final assumption, that

self-development is a matter only for the individual, can be dealt with in a

similar manner. Precision allows us to see that this assumption is not a fact,

it is merely something that �I think.�

With gentleness, we begin to ask ourselves �Why do I think this? Why do I think

that self-development is a matter for the individual? What experiences have

contributed to this idea? How do I feel about my achievements and myself when I

think this? Isn�t it interesting that I have these feelings around this issue?!

Why do I feel that?� Through this process, through gentleness with ourselves,

we let go of the assumption. We begin to see that many people have helped us in

our development, and that we have helped many others. We begin to see the

community that already exists among anthroposophists. The community that is so

important to our development, and which so many people seek today. We realize

that it has only been our assumptions and our harshness with ourselves that

have kept us from participating fully in this community as a student, and as a

teacher.

When we let go of our

assumptions about attainment, the teachings, and the role of the community, we

free ourselves from the dysfunction that occurs when the three jewels are

misunderstood. The three jewels of Buddhism, and of Anthroposophy, are then

able to function in harmony. The whole that becomes visible has always been

present. Its radiance has just been temporarily obscured by our assumptions.

Once we are free of these, the jewels are able to shine again. The qualities of

precision, gentleness, and letting go, enable us to embody that spiritual power

of love that Manfred Schmidt-Brabant speaks of at the end of his final lecture.

Then we manage to break

through the walls of occult imprisonment with the only thing that can break

through, the power of love in a spiritual way.[25]

This spiritual power of

love is not something abstract. It is a real force in our lives. We only have

to allow it to manifest itself. Recognizing the three jewels of Anthroposophy

can help in this process.

References

Anonymous. 2001. A glossary of Pali

and Buddhist terms. http://www.accesstoinsight.org/glossary.html

Barkhoff, M.

2000.Exchanging spiritual experiences. Anthroposophy Worldwide No.10, December

2000. p. 2

Brodersen, S. 2000. Our activities

are not �better� than theirs. Anthroposophy Worldwide No.10, December 2000. p.

2

Bullitt, J. 2001. What is Theravada

Buddhism? http://www.accesstoinsight.org/theravada.html

Ch`dron, P. 1991. The wisdom

of no escape. Shambhala, Boston.

Franklin, N. V. P. 1989. Prolegomena to the study

of Rudolf Steiner�s Christian teaching with respect to the Masonic tradition.

Dissertation, University College, Cardiff, Wales.

Marcum, U. B. 1989. Rudolf Steiner: An

intellectual Biography. University of California, Riverside. [Available from

UMI Dissertation Services, Ann Arbor, MI, USA (order no. 8915938)]

Samyutta Nikaya LVI.11

Dhammacakkapavattana Sutta [Setting the Wheel of Dhamma in Motion]

http://www.accesstoinsight.org/canon/samyutta/sn56-011.html (Translated by

Thanissaro Bhikkhu).

Schmidt-Brabant, M. 2000.

Collaborating to meet the destiny of our time as pupils of the spirit �

Michael�s signature in the present. Journal of the Anthroposophical Society for

cultural, social and economic research in Australia. December 2000. pp. 3-4[26]

Shepherd, A. P. 1983. Scientist of the invisible.

Inner Traditions International. New York, NY.

Steiner, R. 1909/1994. How to know

higher worlds. Anthroposophic Press. Hudson, NY. (Translated by Christopher Bamford)

Steiner, R. 1913/1985. Self Education:

Autobiographical reflections 1861-1893. Mercury Press. Spring Valley, NY.

(Translated by A. Wulsin)

Steiner, R. 1925/2000 Autobiography.

Anthroposophic Press, Hudson, NY.