But now back to my original posting in Buenos Aires — and this memoir gets interesting.

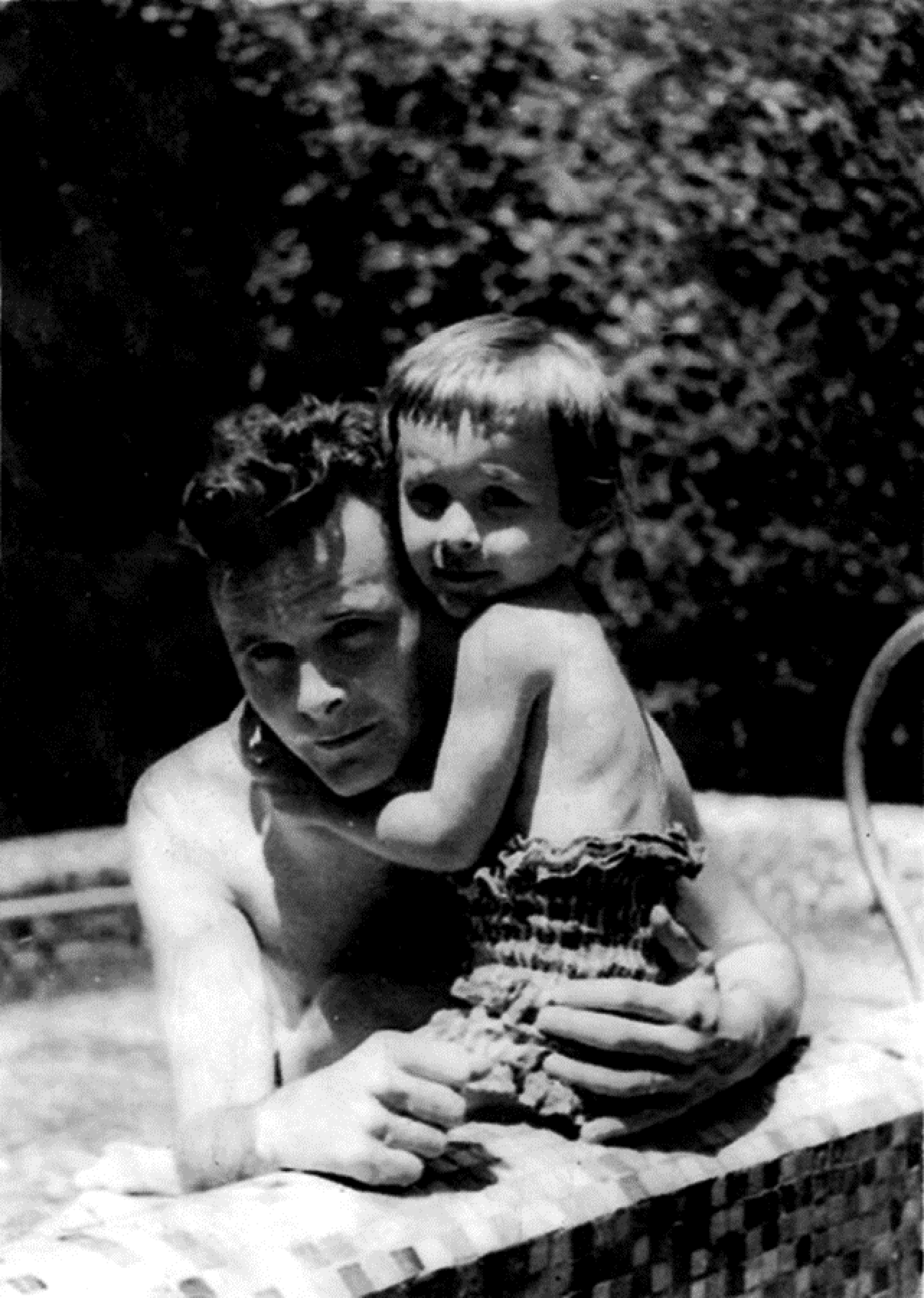

We (Renate, our three-year-old daughter and I) were stuck in a temporary apartment in downtown Buenos Aires while looking for something more appropriate and affordable. I had no office, so between visits to airlines and getting to know the territory, I often just wandered around the city.

An uncle of Renate's, Uncle Karl, was an anthroposophist and when he learned that we would be living in Argentina, he wrote to Renate that there was a Rudolf Steiner School in Buenos Aires, which we could consider for our Beatrice. So, when I came upon a German bookstore one day, I entered and asked in German if they knew where the Rudolf Steiner Schule was. The owner was happy to oblige. He looked up the address and told me “Warnes 1331 Florida.” Warnes meant nothing to me, but Florida was one of the main streets of Buenos Aires. Because in New York, and America in general, the house or building number comes before the street name, I thought the address of the Rudolf Steiner Schule was 1331 Florida Street.

As I was one block away from Florida Street, I walked over to it and saw that the numbering was at the 500 block. I had nothing better to do, so I decided to walk down Florida Street until I arrived at 1331 and the Rudolf Steiner Schule. However, when I arrived at 1100, Florida Street ended. I feared I might fall into the great River Rio de la Plata by going on much farther. Concluding that the bookstore guy had given me the wrong address, I shrugged and forgot about it.

There were two German language newspapers: one very right wing, in fact close to Nazi; and the Argentinisches Tageblatt, centrist, perhaps Jewish oriented. We looked through the classified sections of both newspapers, looking for a house or a more comfortable apartment for rent, but found nothing of interest. Finally, in desperation, we put an ad in the Tageblatt in German. We received a call the next day offering a small house in a suburb at a reasonable rent. We agreed to meet the owner at the central railroad station, Retiro, in order to travel with him to the suburb of Florida.

The house he offered was perfect. It was small, but just right for

three people. It also had a garden in the back and even a small swimming

pool. The train from and to Buenos Aires was hourly and took only twenty

minutes. We took it immediately.

It turned out that Florida had many German residents, most of whom had arrived after World War Two. Among them were also German Jews, such as the owner of our house, and Nazis, something we were to learn later the hard way, for none of them admitted to being or having been admirers of Hitler.

Our next-door neighbors were ethnic German Mennonites. The family told us, after we got to know them better, that they were originally members of a German Mennonite colony in Russia, whose lives were made impossible by the Soviets. Many emigrated to Canada. Others, including our neighbors, went to Paraguay, where they began to build a Mennonite colony from scratch in the jungle. That life was too hard for them, so they continued on to Argentina. They were very good people and helped us get acclimated.

They told us that there was a German school a few blocks away. It turned out to be the Rudolf Steiner Schule that Uncle Karl meant. “Warnes 1331 Florida” didn't indicate Number 1331 Florida Street, but Warnes Street Number 1331, Florida. Warnes was a soldier who fought in the Argentine army in the war of independence from Spain in the eighteenth century. That I had not been able to find that school on my own and that we later wound up living near to it without realizing it, did not seem more to me then than a coincidence. After the events that occurred over the following years, however, it seemed more likely that we had been somehow led there.

Bibi’s mother tongue was German, despite having been born in the United States, so when she went to the kindergarten where German was mostly spoken, she blended right in. After a year or two I was curious about some aspects of the so-called Waldorf method. The first school, founded in Germany in 1919, was meant at first for the children of the workers of the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory, the owner-director being an anthroposophist who wished to put some of Rudolf Steiner's ideas about education into practice. I don't remember the question I asked Tante Ingeborg, Bibi's kindergarten teacher, but apparently it was over her head. She referred me to Erwin Kovacs. I called him and he invited me to his home, not far from Florida, to discuss my question. I went in my new car, a Citroen CV2, a small toy of a car and a lot of fun: air cooled motor in the back, convertible. It was cheap and the first new car I'd ever had.

Erwin Kovacs turned out to be a priest of the Christian Community, a church based on Rudolf Steiner's teachings about Christianity. I was beginning to think there was nothing that guy didn't give teachings about. The church was in a private house, recognizable as a church only by a sign outside on a scrawny lawn. (Years later a young parishioner received an inheritance and donated enough of it to build a small but well-appointed and artistically tasteful “real” church.) After answering my question, whatever it was, Kovaks asked me if I would like to join a new study group which would meet once a week in his house/church. Subject: The Gospel of Luke by Rudolf Steiner, in German of course.

Including Kovacs, there were five of us in the group. I found the text of Steiner's lectures interesting, but I had difficulty understanding it. The German being read by Kovacs was of a strange style, for me that is. But it was a beginning.

My daughter was very happy in the kindergarten, where she also picked up Spanish from the other children. It had been my intention that she go to a nearby English primary school so she wouldn't lose her English. But she was so happy where she was and with the friends she had made, that we finally decided that she should continue in the Rudolf Steiner primary school (a good choice).

One day when she was in the second-grade, thunder struck — so to speak.

When I came home from work, Renate told Bibi to repeat to me what happened in school that day. Bibi told me in German: we were in music class when Frau X, the eurythmy teacher, opened the door and said to Fräulein Oehring, the class teacher: Time for eurythmy. But Fräulein Oehring said No, we're in music class. Frau X slammed the door. Later Fräulein Kutschmann, the physical education teacher, entered with another teacher, a man, who grabbed Fräulein Oehring by the shoulders and pushed her into the corner and Kutschmann said loudly, stand up children and come out to eurythmy. We were afraid but we stood up and went out into the hall where Frau X was waiting. We followed her downstairs to the auditorium where we had eurythmy class.

I was astonished and very worried. I said to Renate, “Something must have happened, but it can't be that. I mean children often exaggerate about something they don't understand.”

A short time later the phone rang. It was Hoffman, a German father of a child in that class. He sounded nervous and asked if my daughter had told us what happened in class today. I said yes, but I can hardly believe it. What did your daughter tell you? Hoffman told me exactly what Bibi had told me. We agreed that something must be done. I told him I'd contact other parents. There was no need for that. The phone kept ringing, but it was the Argentinian non-German-speaking parents who were calling, probably because we knew German and therefore had a closer contact with the various actors involved.

That same evening Annemarie Oehring (Fräulein Oehring) knocked on our door. She showed us a telegram she had just received from the school´s Board of Directors informing her that she was dismissed, effective immediately. I don't remember exactly what she replied to my asking what happened and why. Basically though, she had previously told the eurythmy teacher that she would not allow her to teach her class any longer. Why, I asked. Because she was aligned with the German nationalists who now ran the school. So, when she came anyway, Oehring told her that they were doing music in the class so the children would not leave with her. Then Kutschmann came, accompanied by a temporary teacher from Germany.

I arranged a meeting at home for the next evening with the parents who had called and Annemarie Oehring. After that meeting, where we decided that we would not accept Miss Oehring's dismissal, I called a member of the Board of Directors I knew and told him that many of our children would not be attending class until we could meet with the Board.

The meeting took place almost immediately. The president of the Board said that Miss Oehring had been fired for insubordination. She refused to comply with the school's program. We replied that she had been physically abused by Kutschmann and that other guy. They said they regretted but understood that people sometimes lose their temper. Finally, after strong words had been exchanged, the president called a short break, during which the Board members left the room. A few minutes later they returned, and the president stood up and declared that the second grade would be taught by another teacher, whom he named, and that any pupils who did not attend would be considered “free,” meaning expelled.

We sat there for a few moments, stunned, Then, however, Miguel Lozano stood up and shouted, “My daughter will not attend class tomorrow, but I will be at the Ministry of Education in Buenos Aires in order to report this crime, this violation, personally.” The rest of us applauded. The Board called for another break. It turned out to be a longer one this time. When they returned, they said that upon reconsideration Miss Oehring could remain as class teacher until the end of the school year, at which time her employment would cease. What we didn't know was that neither Miss Oehring nor many other teachers had Argentine teaching licenses. So, an investigation by the education ministry could be disastrous for the school. They surrendered temporarily because of that, not because of us.

I must jump ahead now a number of years in order to make what follows comprehensible. In late 1974 IATA transferred me to Zurich, Switzerland. The leading German news magazine was, and still is, Der Spiegel. It was and is widely read in German-speaking Switzerland. I bought and was reading the July 7, 1975 issue, and was much surprised to read in the index Der Fall Kutschmann (The Kutschmann Case). I flipped to the article and read how SS-Untersturmführer Walter Kutschmann, a war criminal responsible for the murder of many Jews in Poland, including twenty university professors, had deserted in late 1944 when it was clear that the war was lost. He went to Franco's Spain, where he was warmly welcomed and soon obtained Spanish citizenship under the name Pedro Ricardo Olmo. He also learned Spanish. He then emigrated to Argentina, where he became the sales manager of the important German company Osram. When Simon Wiesenthal, the famous postwar Nazi hunter, found him and informed the competent German authorities in Berlin, the bureaucratic process began according to which Berlin was to inform the German embassy in Buenos Aires, which in turn should have requested that the Argentine police arrest Kutschmann/Olmo (who also held Argentine citizenship) and arrange for him to be extradited to Germany to face trial there. By the time the German embassy in Buenos Aires took a tiny step forward, contradicting the famous German efficiency, Kutschmann had long since disappeared and was never found, although he was sighted and even photographed occasionally. He died peacefully many years later in Buenos Aires.

The fateful strands all came together in my mind. I had known a person in Buenos Aires by the name of Wolfgang Latrille, the director (CEO) of Osram Argentina. He was also the leader of an anthroposophical German-speaking branch.

Latrille had retired around the same time I moved to Zurich, which is a one-hour drive to Dornach, the center of the General Anthroposophical Society. Latrille now lived there in a comfortable house a short walk to the Goetheanum. I visited Dornach with a certain frequency. I had even visited him there once.

I cannot describe here now how I felt upon finishing the article. I kept the magazine, it lies open in front of me now as I write this. I called Wolfgang Latrille.

“Did you read the Der Spiegel article?” I asked him. He knew what I meant, and he was silent for what seemed like a long time but was probably only a few seconds.

“She was his sister,” he finally said. He meant Christl Kutschmann, the physical education teacher who interrupted the second-grade class, as related above.

“And according to the article he worked for you under a false name. Is that true?”

“Yes, but many Germans changed their names in Argentina.” (pause) “And I didn't know he was a war criminal of course.”

I don´t remember how I ended the conversation, but it wasn't friendly. I never saw nor spoke to him again. I had not known of Walter Kutschmann's existence until reading that article.

Back to Argentina in 1966.

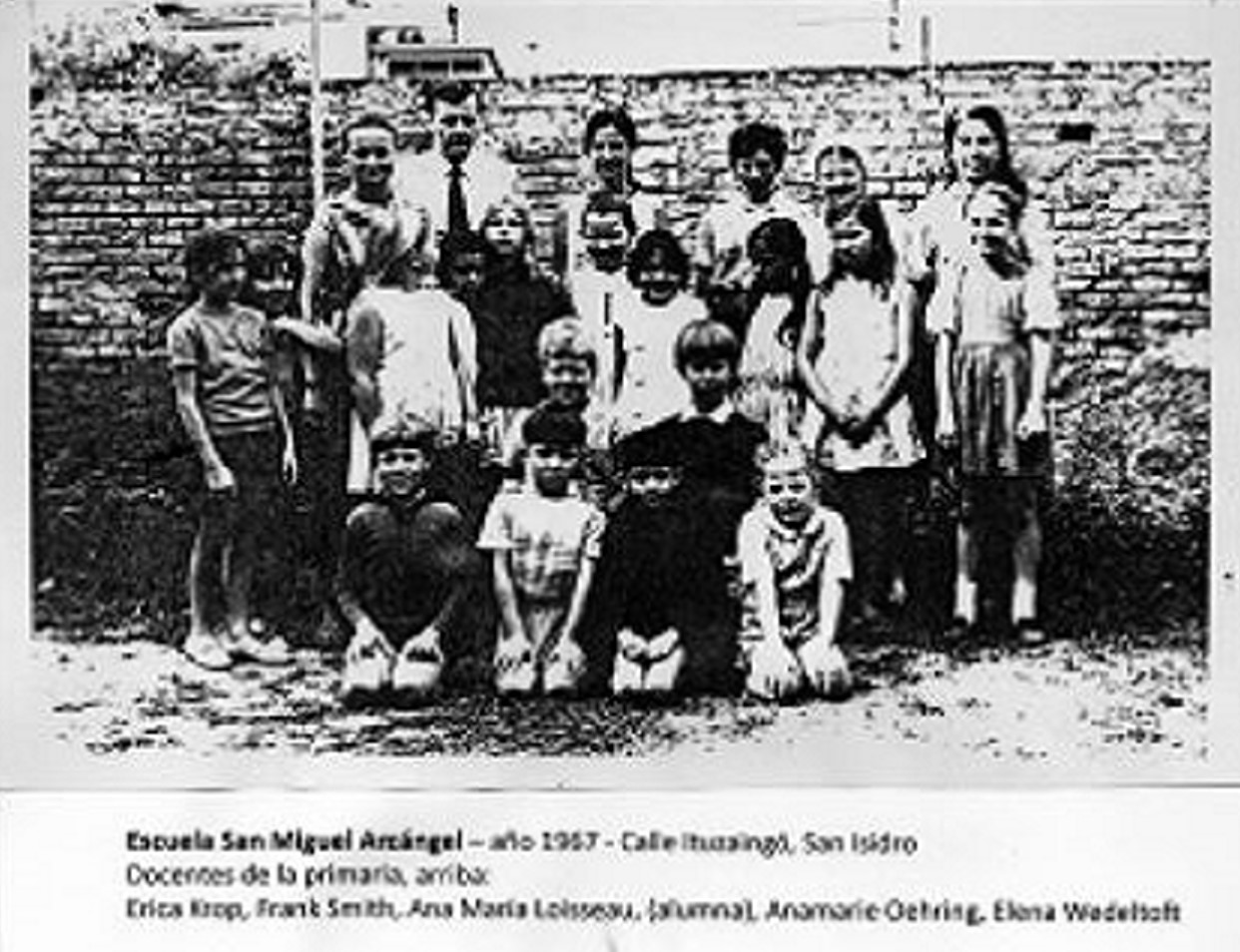

A continuous stream of meetings ensued. The following were the parents involved — the ones I can remember at least. Elena and Svend Wedeltoft. Despite the family name, they were both born and bred Argentinians. Elena became a class teacher for many years in the school we founded, and in another which she co-founded, until her death in 2023 at ninety years of age. Miguel and Ana Lozano, Margarita and Bruno Widmer (Swiss immigrants), Vladimir and María Belikof (Russian immigrants), Saúl and Lidia Gurfein (born Argentinians), Hoffman (a German immigrant), and a few others.

We finally decided to try to take over the school in the next general meeting of the non-profit civil association, the school's legal owner. This required a political campaign, during which we intended to inform the other families with children in the school about what happened that infamous day in the second grade. And how the teacher, who was the violently abused victim, would be fired at the end of the school year. We also announced that we intended to install a new Board of Directors at the next general meeting.

The opposition did it much more efficiently. They had access to all the other families to whom they warned about a small but evil group wanting to take over the school. They also had the written support of the Bund of Waldorf Schools in Germany. In short, the general meeting, which was usually boring, and few members normally attended, was attended that year by a record number of members. (All parents were automatically members of the association.) We lost the vote by a landslide. Therefore, we decided to take out our children and found a new school using the same educational method: Waldorf, and with the same teacher: Annemarie Oehring.

We found an old house to rent in San Isidro, a suburb farther from Buenos Aires than Florida. It was a one-story house with four adjoining rooms all opening out to the patio, or garden. It was simpatico, but impractical. The kindergarten was far to the rear with its own sandbox.

The owner, a young Anglo-Argentine who had grown up in the house and inherited it, came to visit every month to collect the rent. He was as helpful as possible as long as it didn't cost anything, for he was far from wealthy. There was an avocado tree in the center of the garden. He told us how it hadn't borne fruit in many years, so he was surprised that it now had so much fruit that you had to be careful when you walked under it so you would not be conked on the head by one falling. Annemarie Oehring said it was because of the children, that the tree felt and enjoyed their presence, for it was otherwise all alone.

Actually, Annemarie Oehring had been reluctant to make the move instead of remaining in Florida with her mentor, an interesting personality named Herbert Schulte-Kersmecke, the architect and co-founder of the school there, and continue the battle. But she finally realized that she had no choice and became the new school's first and only teacher who knew anything about Waldorf pedagogy.

We first named the school Escuela Waldorf Argentina, which was not only silly, but also an error. We soon received a letter (in German) from the Bund of Waldorf Schools in Germany stating that we had no right to name our school “Waldorf” and demanding that we change it. I answered that they had no patent on the name in Argentina (which they did in Germany) and so had no right to demand that we change it.

Someone suggested San Miguel, because Steiner had indicated that Miguel was the patron archangel of our times. But it was objected that San Miguel was the name of a nearby town. So, San Miguel Arcángel was finally decided upon, despite it sounding Roman Catholic. Ironically however, that was a stroke of good luck during the later military dictatorship; they considered the Catholic Church to be a reliable ally in the fight against communism.

One day Annemarie Oehring — la Fräulein, as almost everyone called her — said to me that I would have to teach the children English, that she couldn't be the only teacher all day long. She needed to rest. Also, she didn't know English. Well, but I had no idea how to teach English. “Use your own initiative,” she said.

I went to an English bookstore in Buenos Aires and bought two books. One was a story about King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table (I bought a dozen copies so each child could have one). The other was an English grammar book for children. I read the King Arthur book, and the kids could follow the text in their book ... theoretically. In practice they listened, waiting for me to translate into Spanish. Either way, it went well. The other book was to learn simple grammar, which we should be doing now in the third grade. It explained grammar rules, then provided multiple-choice questions. I thought of it as a kind of game. The kids didn't seem amused though. On day Annemarie (la Fräulein) said to me, "Why are you using that awful grammar book?" I was somewhat taken aback. "Do you have a better one?" I asked her. "Look," she said, "you have that lovely story book." She meant the King Arthur book, which was indeed lovely, illustrations and all. She went on: "Use that. You read a paragraph or a sentence and explain the grammar behind it, nouns, adjectives, etc." I grumbled an agreement of sorts and during the next few days I tried it. It worked like a charm. The children were fascinated that King Arthur and Sir Gawain and the rest were all bounded by grammatical rules they never violated, even when saving damsels.

At the beginning, I was teaching English to one grade from 8 to 8.45 one day a week before skedaddling downtown (20 minutes by car) to my official day-job. It was only me in the office and a homemade telephone answering machine invented by a local genius before they went viral in the first world. But as the school grew, so did my English teacher duties. Before I knew it — it was, after all, gradual — I was teaching five days a week, not to mention administration and meetings and crises solving.

One morning I was sitting at the secretary's desk, don't remember why, perhaps she was ill, when a young woman entered and asked to speak to the directora. Actually, we didn't have a directora, or a director for that matter, or stated more accurately, we had several. I invited her to have a seat across from me, thereby implying that I was the director. She was a slight, attractive woman with deeply infused worried dark eyes. She had come to ask about enrolling a child, which is what I suspected.

“My daughter is in the first grade in the public school two blocks away,” she explained. “She doesn't like it at all, in fact she is often ill or pretends to be in order to avoid having to go.” I nodded to indicate that I understood and so she would continue. “We pass by here every morning, and we see the children running and laughing and obviously happy to be going to school here.” She paused and stifled a sob. “Why? What are you doing here that might be what my daughter needs?”

I don't remember exactly what I said beyond the usual making lessons so interesting that the children want to learn. I hope I mentioned the most important of the many things I'd learned until then. That official education, that is government run schools as well as private ones, think that the earlier you start teaching children, the more they will learn. So, if they can't read by the first grade they're stupid or the teacher is incompetent. According to our methodology, this is completely false. Teaching such an important subject as reading should be taught only when the child has reached the point in development when it is sufficiently developed to easily learn, thus, to really want to learn to read. To force the child to read before that — usually in the first grade — can be psychologically damaging. Furthermore, we teach “artistically.” That is, the individual letters are drawn and colored and animated in the first grade. I suggested a meeting with Miss Oehring. That happened and the child (I'll call her Ana) began the first grade in the middle of the school year. I'm not sure who the class teacher was, but I think it was Elena Wedeltoft. Annemarie told her to let Ana be a listener, seated in the rear, don't call on her for anything, just let her awaken on her own.

I followed the same instruction in English class. And one day it happened: I asked a question to the class in general about some story. The usual hands shot up wanting to be chosen to reply. Ana's was one. As casually as I could sound, I said “Ana?” Heads turned. The children had been told by Annemarie Oehring, before Ana's first day, that she was frightened and timid, that the other kids should try to help her, ask her to play during breaks, etc. What was not said, but what was behind the words, was that Ana should not be made fun of, laughed at or bullied.

She answered correctly. I swallowed my relief and merely said, “Right.” The other children smiled, as though they all had answered collectively. Ana was integrated for good, and now loved school instead of hating it.

Meanwhile I still had my day-job, from whence I earned a living for myself and family, which, by the way, had grown considerably: a son, Marcos, who also eventually became a pupil in SMA, and, later, Natalia, who squeaked into kindergarten before we left Argentina.

Now we were two Compliance Officers. Adil Goussarov, son of Russian emigres to France, then to Argentina when he was a boy. He had worked for Swissair in Buenos Aires as ticket office manager, then for Argentine Airlines in New York, then for IATA in New York as Mr. Feick's assistant. So, he knew the airline business. I never knew if he asked to return to Argentina or if Feick wanted someone else here, for I certainly was very busy, even without the school. Besides being colleagues, we became personal friends.

I suspect the latter, because several months before Goussa (as he was called) arrived Mr. Feick himself visited, with Mrs. Feick. He was making the rounds of the many places we had officers. I invited them home for tea; Mr. Feick requested that Osvaldo Romberg also be there. So, there were five of us: Mr. and Mrs. Feick, my wife Renate, Osvaldo and I. I don't remember the conversation, but it must have been quite general. Osvaldo didn't say a word, except when Feick asked him directly, and then he didn't readily understand. He had to ask for a repeat, or I had to translate. The next day he told me the meeting was torture for him, that he sat directly across from Mrs. Feick and the way she crossed her legs he had to see everything. “It was disgusting,” he added and laughed. I had to laugh as well, because I thought that he had at least survived. When I took the Feicks to the airport the next day, last thing Feick said to me was “Fire Romberg.”

Osvaldo was neither surprised nor particularly disappointed. He would miss the salary of course, but he was not at all interested in IATA or the airline industry. He was an artist. He emigrated later to Israel, where he became a successful painter as well as a university instructor. He was no longer necessary as an interpreter for me, but he was an invaluable source of “intermediaries” to buy test tickets with discounts. His friends and relatives were always good actors.

Laimonis

One day, after I had been in Argentina for a year or two, I had occasion to visit Air France's office. In those days most airlines had well-appointed ticket offices in downtown Buenos Aires on streets with much pedestrian thoroughfare. Almost all airlines were owned by their national states, for whom showing the flag was more important than the profit and loss column. Air France's office was at the corner of Florida and Paraguay Streets, a truly ideal location. I needed to speak to the ticket office manager, so I was directed to a windowless office in the basement. The manager was Laimonis Holms, five years older than I, born in Latvia, escaped the Soviet Russians as a child first to Germany (learned German), then to France (learned French), then to the United States (learned English) and finally to Argentina.

The first indication about something unusual about Lai (for short) was that during our conversation he asked me if I had the time. There was no clock on his desk nor any of the walls and I presumed that his watch was being repaired. I mean after all, an airline manager who doesn't even know the time! No way. I soon learned that he owned no watch. Something to do with Krishnamurti's teaching about time. Every time I met him in his office he asked me for the time.

In Argentina I was known as the “Inspector IATA.” As such I was forbidden to accept gifts from airlines, with two exceptions: free and reduced fare travel on business or vacation; and lunch. The latter because someone had convinced Feick that lunch together with an airline manager was when (after wine) information could be obtained about certain market conditions, such as “who is doing what.” Most airline managers were keen to invite me for lunch for two reasons (although there may have been more): become friendly with me in order to determine if I could be trusted with confidential information, and a free lunch for themselves. It all went on the expense account.

Lai invited me for lunch at a first-class French restaurant in Buenos Aires. I ordered the chef's special, and Lai ordered something else. While eating I mentioned how delicious it was. He said "yes, but I don't eat meat.”

I was surprised for he was such a healthy-looking guy. I was still under the false impression that meat is a necessary element of a healthy diet. “Never?” I asked. He smiled: “Never, for many years.”

Thus began my life-long practice of vegetarianism. I don't remember what else Lai told me during that lunch, but it was probably careful, something I also learned. When explaining vegetarianism to a questioner, don't act as though you think he or she is an idiotic carnivore. He asked me to pass by his office the next day, when he would loan me a book that explains vegetarianism. The book was The Case for Vegetarianism (or a similar title) by the president of the British Vegetarian Society. I swallowed it whole (pun intended). It spoke about the reasons for abstaining from meat were essentially health (meat is toxic) and morality, cruelty to the animals we kill in order to eat them. A third, most important reason was unknown in those days: the fact that each year a single cow will belch about 220 pounds of methane. Methane from cattle is shorter-lived than carbon dioxide but 28 times more potent in warming the atmosphere, the notorious “cow burps and farts” problem. Raising cattle is estimated to be responsible for at least 15 percent of global warming.

I had always been a carnivore, and more so since living in Argentina, a country with more cows than people and a huge meat industry, for local consumption and for export. On most workdays I had lunch in a good restaurant consisting of a steak, french fries, wine, a sweet dessert and coffee. Afterwards only a siesta was possible. I often didn't feel well or had a headache. All that changed when I decided to become a vegetarian literally overnight, and I owe it to Laimonis Holms. Lai, by the way, lived to be 93 years old. He will appear again in this memoir.

The Threefold Society

I was getting more interested in anthroposophy, and not only in respect to education. Annemarie Ohering told me that the first Waldorf school was founded in 1919 in Germany by one of Rudolf Steiner's followers, Emil Molt, who was the owner and director of the Waldorf Astoria cigarette factory. It was meant at first for the children of Molt's employees and was based on Steiner's educational ideas. Also, because Molt wanted to put into practice Steiner's social ideas, namely the “Threefold Society” or social triformation.

She mentioned something about the rights sector, the economic and the spiritual ones. I soon realized that she had neither the time nor the ability to go further into the subject, but she loaned me Steiner's seminal book: Die Kernpunkte der sozialen Frage Basic Issues of the Social Question.) Later when I lived in Switzerland, I translated it. It was published in the U.K as Toward Social Renewal. The latest edition is titled Toward A Threefold Society, published in the United States.

It is not an easy book, but it astonished me to realize that the same individual, Rudolf Steiner, whose work was the foundation of Waldorf pedagogy and who had spoken and written about angels, devils, religion, reincarnation and karma, had also introduced concepts about how society should be organized and renewed in a rational, practical way.

Basically, he said that society consists of three elements: politics (the rights state), economy (production, distribution and consumption of goods) and the cultural or spiritual sections (especially education). The defining characteristic of the political state is equality; the defining characteristic of the economy is fraternity; and the defining characteristic of the spiritual-cultural sector is freedom. The problem is that each of the three sections should be autonomous — or at least semi-autonomous — whereas they are combined and confused. For example, the political state controls education when it should be a factor of a free cultural section of society. The economy should not be controlled by the state nor by the “free” market, which doesn't exist. Rather it should be determined together by associations of producers, distributors and consumers.

Having been working for many years in the airline industry I saw how this would function with airlines, travel agents and passengers together deciding fares and travel conditions.

The last paragraph in the book especially interested me:

“One can anticipate the experts who object to the complexity of these suggestions and find it uncomfortable even to think about three systems cooperating with each other, because they wish to know nothing of the real requirements of life and would structure everything according to the comfortable requirements of their thinking. This must become clear to them: either people will accommodate their thinking to the requirements of reality, or they will have learned nothing from the calamity and will cause innumerable new ones to occur in the future.”

The calamity referred to is the First World War, and since that time history has certainly shown these words to be prophetic. I am writing this in 2024 and since first reading the book in 1969 I have witnessed many and more terrible calamities, and the future looks bleak indeed.

In 1919, when the book was written, the Soviet Union was still in formation — a political-economic-cultural dictatorship. Then came the Second World War, more terrible by far than the First. But the wars (cold and hot) never ended: Korea, Vietnam, etc. And even now as I write in 2024 the Middle East is about to explode in Israel's face and Russia and Ukraine are fighting to the end. The calamities have been occurring 'innumerably' ever since. The 'social question' has not been resolved, nor have the steps been taken which are necessary to initiate the healing process. We all too often still look to the political state for the solution to all social problems, whether they be of an economic, spiritual (cultural), or political nature.

While still near the beginning of the translation I began to look for a publisher. I knew that Saul Bellow, at the time one of America's leading authors, was a member of the Anthroposophical Society. He was also very influential with the University of Chicago Press. I sent a copy of what I had translated so far and asked if he'd be interested in writing an introduction once it was finished. I was surprised that he even answered, and more so when he asked me to send the finished MS to him and he would decide then. But while I was still working on it — with a typewriter and dictionary — I heard that the Rudolf Steiner Press in London had a new editor who was interested in reorganizing and publishing good translations likely to sell. I sent him what I had done by then, about half the book, and he made a commitment to publish upon completion 3,000 copies in hardcover and 3,000 in paperback and pay me six percent royalties. I also figured that the Rudolf Steiner Press would keep the book in print, which they did. I wrote to Bellow thanking him for his interest and promising a copy of the book when published.

My interest in anthroposophy extended to joining the Anthroposophical Society. The first anthroposophical seeds were planted in Buenos Aires in two different places and in two different cultures with two different languages: Spanish and German.

The German side

In 1920, a young German student, Fred Poeppig, arrived in Buenos Aires with some books by Rudolf Steiner in his suitcase. He had recently discovered Steiner in Germany and was determined to study his work. He announced the formation of a study group in a German language newspaper and put the necessary fervor into the group's formation. He returned to Germany in 1923, but the group seems to have continued to meet until the outbreak of World War II in Europe in 1939, when it became politically inconvenient to continue with a foreign group, which required registration with the authorities. The group then disbanded.

At the same time, however, there was another group of German anthroposophists who adopted a different attitude: they considered it "un-anthroposophical" and cowardly to suspend their activities because of the government's directives and preferred to ignore them. This was the "Arbeitsgruppe Florida" located on the outskirts of Buenos Aires, in the town of Florida. It was headed by Herbert Schulte-Kersmecke and had about ten members. To put their ideas into practice, they founded a kindergarten and, in 1946, an elementary school in a building designed by Schulte-Kersmecke. All in German, of course: the Rudolf Steiner Schule. Once the war was over more Germans immigrated to Argentina, displaced from Europe and China, among them Jews and Nazis. The latter were very well received by the government of Juan Domingo Perón. They entered carrying Vatican passports with Argentine visas. Perón even had a department of his government dedicated to helping war criminals enter.

The Argentine side

Around 1931 Domingo Pita, a member of the Theosophical Society in Argentina, found some works by Rudolf Steiner translated into French which, especially because of the Christian content of anthroposophy, interested him greatly. He organized a study group in his home in Buenos Aires. He translated some of Steiner's basic works into Spanish from French and Italian versions. The group continued its meetings until 1942 when, due to the war and Pita's health, it ceased its activity. I don't know if during all that time either of the two groups, the German and the Argentinean, knew of the existence of the other.

In 1953, the Argentine group was revived at the initiative of Enrique and Lydia Lambrechts. Domingo Pita (son), Antonio and Beatriz Artuso and Arturo Habegger were also part of this group, among others. They published a magazine called "Antroposofía.”

This group founded a Waldorf School in 1961 with the name Colegio Saint Jean. The school grew successfully until the founding teachers succumbed to parents' pressure to expand by adding a secondary school. This meant that many secondary school teachers had to be brought in who knew nothing about the Waldorf method and obviously nothing about anthroposophy. Finally, supported by a group of parents who were opposed to the Waldorf method and anthroposophy, they took over the school during a general meeting of the civil association in 1975 and the Waldorf teachers resigned. The school became an ordinary private school with no connection to Waldorf education.

There was resentment within the Argentine group towards the German groups in the northern suburbs, especially Florida, because some Germans felt that Argentinians, as Latinos, had less spiritual development because they were still mired in the sensitive soul, instead of having reached the level of the consciousness soul as they, the Germans, had. Although this was not true of all the Germans, I can confirm that the feeling of superiority existed in some of the German-speaking groups.

There were four anthroposophical "branches," three German-speaking and one Spanish-speaking. I attended the Spanish-speaking one (Saint Jean), even though I lived at the other end of town, because its members were warm and open. The German groups were antagonistic towards our new school because of the conflict with the Florida school. The Argentine group on the other hand, was very encouraging and friendly. They even donated a piano of excellent quality for the new school. And there was something else I will never forget.

Before I arrived in Argentina, a German named Volkfried Schuster lived here. He was an anthroposophist who made his living working in construction and he was in contact with both sides, especially with the Argentine side. He was very much appreciated by the Argentinians, who considered him a friend who helped them with their questions about anthroposophy. It must be remembered that there was very little anthroposophical literature translated into Spanish in those days. Schuster had left the country shortly before I arrived.

When Enrique Lambrechts died, I went to his wake. He was a member and co-founder of the Argentine anthroposophical group and a good friend. Enrique's wife, Lydia, asked me if I would do them a favor the next time I went to Switzerland. It had been Enrique's wish to give his best suit to his best friend, Volkfried Schuster, who lived near the Goetheanum in Dornach. I had never heard of this custom and it pleasantly surprised me.

The next time I traveled to Switzerland I went to a beautiful house of organic structure located about 200 meters from the Goetheanum, on the street that leads up the hill to it. I rang the doorbell with the package containing Enrique's suit under my arm. A young woman opened the door and when I asked for Herr Schuster, she, his niece, asked my name. I told her, but I knew it would mean nothing to her or to Schuster, so I added: "from Argentina.” That brought Schuster to the door. He was very surprised when I explained my mission. He did not know that Enrique Lambrechts had died and, when I handed him the suit and explained why, I observed that he was very moved, almost to tears. He ushered me into the living room to meet his sister, a beautiful woman named Maria Jenny (née Schuster) one of the original eurythmists, when Rudolf Steiner was still alive. In time, she would become the last living person who had personally known Rudolf Steiner.

Outside in the garden a peacock unfurled its tail, as if in greeting. I was invited to spend the night there, and afterwards, whenever I went to Dornach, I would stop by to say hello to Maria Jenny (Volkfried Schuster had returned to Germany, but we kept in touch by mail). Maria died in 2009, at the age of 102.

NPI

I wrote an article for the English version of the General Anthroposophical Society's Newsletter entitled “The Forgotten Threefold Society,” because I had not seen the subject even mentioned in the German publications I had been receiving. It was not only published, but also translated into German for “Das Goetheanum” weekly bulletin.

In 1970 or 1971 there was an international meeting planned at the Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland. However, despite numerous requests to the Vorstand (Executive Committee), the subject of Social Triformation/Threefold Society was not included. So, a parallel, unofficial event was organized in a house close to the Goetheanum. I took a few days’ vacation and flew up. There were about a dozen participants the first day in the parallel event and double that the second day. I met some very interesting people there, including Wilfried Heidt, Lex Bos, Gerhart von Beckerath, among others. The stated reason the Society refused to include the Social Triformation (or Threefold Society) was because it is political and the Anthroposophical Society may not engage in politics, was considered simply stupid. Wilfried Heidt offered to organize a meeting in his Cultural Center in Achberg, a town in southern Germany. It was unanimously agreed upon.

It was a time of serious social and political change. A “velvet” revolution — “communism with a human face” — had occurred in Czechoslovakia, which the Soviet tanks had promptly crushed. Many Czechs had fled to Switzerland and Germany. They were invited to the Achberg meeting, and several came, including the Czech ex-economy minister. I also attended and led a group on the subject in English. The meeting was well attended, mostly by Germans, Swiss and Scandinavians. But afterwards, despite trying to spread the idea of a threefold society, nothing concrete happened.

I had made contact with Lex Bos though. He worked with a most unusual Dutch company called NPI — Netherlands Pedagogical Institute. It was and still is an anthroposophically oriented organization development consulting company. It doesn't teach anthroposophy, but the consultants are anthroposophists who help normal companies with their social — and efficient — development. They had been quite successful in Holland and were in a process of international expansion — not of their company, but in the training of consultants who could then go back to their own countries to work with the NPI method.

Lex Bos had already been to Brazil, and I asked him if he would like to visit Argentina on his next trip. He readily agreed. I arranged for some speaking engagements, for example in the German Club, for he spoke fluent German. Spanish was more difficult as an interpreter had to be used. I asked him about NPI, and he invited me to visit their headquarters in Holland the next time I was in Europe. I did so and was greatly impressed. It was in a large private villa in a beautiful garden. The various consultants had private workplaces, not offices but two or three in each of the large rooms. All were very cordial to me, speaking either English or German. Before I left Lex asked me if I would be interested in working for NPI instead of what I was presently doing (IATA), which I found unrewarding and unimportant. NPI would give me the opportunity to do the kind of work which greatly interested me, and which I thought had value for society and was related to anthroposophy.

In 1974 Argentina was a dangerous place, especially for foreign executives. Certain revolutionary groups, such the Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (ERP) or Los Montoneros, both of which idolized Che Guevara, fought for a violent socialist revolution against the corrupt Argentine government and its capitalist society. The manager of Swissair, who was not only a colleague but whose daughter attended our school, was kidnapped by the ERP. After a few weeks Swissair paid a ransom of 5,000 Swiss francs to the ERP's numbered account in a bank in Geneva. The victim was released with instructions to leave the country within 48 hours, or else. He complied of course. Airline managers took to moving their offices to Montevideo, Uruguay. I lived in Martinez, a suburb of Buenos Aires and drove to work by different routes in an attempt to avoid becoming the next victim. We were three in our IATA team by then. Adil Goussarov and Julio De Angeles were Argentine citizens and were considered locally hired. I was a foreigner. I presumed that IATA had kidnap insurance but didn't know to what extent it covered locally hired employees.

The offer from NPI had several advantages. First of all, it was work I was greatly interested in and wished to do. It also got me and my family out of Argentina during that dangerous time. The disadvantages were that my salary would be less than a third of my IATA salary, and after one year with NPI in Holland I would be on my own. I'd have to decide whether to return to Argentina or go to the United States. Either way, it would be as an organization development consultant starting out. Not to mention a new language, but since we all spoke German, the NPI people were sure we'd have little difficulty learning Dutch, which is similar. Another uprooting for the kids!?

Renate was of two minds. Starting over in a new country in a new language frightened her somewhat, but getting out of Argentina and to Europe at that time was certainly attractive. I told Lex Bos and the NPI yes, I would quit IATA, and my family and I would move to Holland as soon as possible.

They scheduled an introductory meeting for us new people. There were four or five of us. I remember one from Brazil, another from South Africa. We met Bernard Lievegoed, the founder of NPI and several other initiatives in Holland. I had already read one of his books and was very impressed by it. When he gave us a short welcoming talk, I was then very much impressed by him. One thing he expressed I will never forget. “We are the lucky ones” he said. “We have anthroposophy, so we have a moral obligation to help those who do not have it, when we can.”

The NPI consultants did not teach anthroposophy, did not even mention it unless asked. They merely wanted the people they were in contact with to consider their lives worthwhile, to have meaning. NPI was criticized by certain anthroposophists for helping capitalists become greater capitalists. But they were, and probably still are, missing the point. They would at least have to attend one of NPIs seminars to avoid missing the point.

Back in Argentina I was writing my resignation notice to IATA. I asked in it if IATA would pay for our transportation to Holland. They were more or less obliged to pay for our transportation to New York, where we started from, but Europe was still an open question. I would also have to give at least two weeks' notice. It was at that last moment, so to speak, when I received a letter from my boss (not Feick who had retired), who was based in Geneva, advising me that I was being transferred to Zurich, Switzerland effective immediately. Surprised? Very. But upon considering it, it wasn't really surprising. We were three in the Buenos Aires office, and I was the only foreigner, so the one most susceptible to kidnapping. I don't know if this was the reason, we never spoke about it. It was also possible that Swissair wanted someone from IATA Compliance in Zurich. Anyway, a choice had to be made immediately. I had been in Argentina for twelve years, much longer than usual for airline managers. There was always the danger of “going native.” We had a guy in Peru who opened a restaurant in Lima that he called “The Cockpit.” It was quite successful with the aviation community in general. When IATA head office heard of it, he was told to close the restaurant or leave IATA employment. He chose the latter option. I had been offered transfers previously, once to Miami, once (almost) to Rome, but I replied that IATA needed me more in Argentina, and I stayed — a good choice. I wanted to stay because of the school, which surely needed me more than IATA did. And, admittedly, I had "gone native.”

But it was different now. The school was quite well founded. In fact one of the last decisions I was involved in was buying a new house for the school. We had a complete primary school together with the kindergarten, but the original house with the avocado tree was no longer habitable. Not only was it too small, a high building was being constructed right alongside with bricks, cement, tools and junk falling into the school yard creating a dangerous situation. Someone found a large beautiful old house for sale on the corner opposite the plaza de San Isidro, which was a public park that could be used for outdoor events, such as physical education. The problem was that it cost the equivalent of US$70,000 in Argentine pesos. For possession 10% was needed, then monthly payments to be completed over a period of two years. We were able to raise the $7,000. But at first, I was opposed. I asked: what about the remaining $63,000? Where is that to come from? I was accused (in a friendly manner) of being a gringo who didn't understand Argentina, where one did not worry about such minor details as the future. An older more experienced teacher said, “If we work well the spiritual world will help us.” That sort of nailed it. The deal was made, I signed and shortly thereafter I left Argentina. At about the same time, the Argentine currency began its “devaluation” in relation to the US dollar. During the last six months of the two-year contract, the school was paying about $10 a month in pesos.

I flew to Holland and spoke with Lex together with one or two others. I apologized and tried to explain my choice without seeming too cowardly. Yes, I could leap into the unknown for my ideals, but I had to think of my family, a wife and three children. They understood and thought that perhaps I could work occasionally with them from Zurich. In fact, they had a man in Bern, the capital of Switzerland, whom I could contact if I wished.