Sebasti�o Salgado:� Snapshot of the Man behind the Camera

Mark

Ostrowski

Sebasti�o Salgado (1944, Minas Gerais, Brazil)

came late to what would be his true vocation; he did not begin to work as a

photo reporter until 1973.� Since then,

he has gone on to receive nearly every major and minor photography award for

his unique brand of engaged documentary work.�

In books like Workers:� An Archaeology of the Industrial Age and

Terra:�

Struggle of the Landless, he shows that his art comes as close as

anyone�s to capturing the human soul�a feat some claim is beyond the bounds of

photography.� All proceeds from his work

go to Instituto Terra (www.institutoterra.org),

a project started in 1998 by Salgado and his wife to promote reforestation

projects for the extensive areas of Brazil�s Atlantic Forest that have been

devastated by too many decades of unchecked, indiscriminate felling.�

The last time I saw him was in 1998, when he

was in Oviedo, Spain, to receive his Prince of Asturias Award for the

Arts.� Now, nearly five years later, he

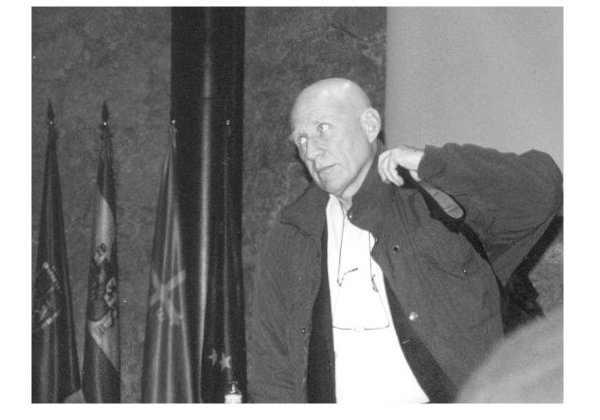

was back to explain the work being done by his Instituto Terra.� His physical appearance remained

unchanged:� the same sharp-featured face

which could not properly be called gaunt; the same bald head; the same

too-pale, too-smooth skin that belies so many years at work in some of the

world�s most inhospitable climes.

The global protest against the war on Iraq had

by this time reached a dizzying pitch, and this seemed to be a confirmation of

Salgado�s notion that we are headed towards increasing oneness, that each of us

is a citizen not of any one nation, but of the world.�

�������� Salgado

talks about far-flung cities with a degree of familiarity that most of us could

muster when describing our own state, region or province; yet, unlike our own

pleasure-driven travel plans, his destinations of choice are where human misery

and suffering are at their most acute.

��������

His eyes have seen terrible

things.� So terrible, in fact, that one

would think that his faith in humankind would have been severely shaken.� Yet this is not the case.� Nearly sixty, he believes that things can change,

if through dialogue and community spirit we make them change.� The recent change of government in his home

country, Brazil, seemed to buoy his hopes in this regard.

The questions from the audience�the

seeming contradiction with then-president of Brazil Henrique Cardoso being

awarded a Prince of Asturias Award the year after he received his own award (by

a long-haired advocate of anti-globalization); advice on how to use his photos

in a primary school classroom (by a teacher); the merit of taking photos not of

people, but of places recently vacated by people (by an aspiring photographer);

and the reason why Salgado himself was never present in his photos (by a

not-so-enticing young blonde)�were fielded with the utmost seriousness, no

matter how absurd.

�Porta�ol� was his language of

choice�Spanish with Portuguese inflexions, with a smidgen of English and

Italian thrown in for good measure.�

Impressive:� he expressed himself

with fluency and naturalness, passion even, never attempting to measure his words,

never choosing words, never taking pause to find the right word to use.��

He said that for him God was the

survival instinct.� The moment we no

longer had this instinct, then this would mean God had left us.� So simple yet so profound, this assertion

had changed his outlook on life.

Among the thousands of refugees he

had met, he said that he had never once found one to be suffering from

depression.� Hunger, thirst, cold, yes,

but depression no.� That was the

particular scourge of the civilized Western world, the cradle of obese

societies in which all needs have been met.

It is easy to cringe in the presence

of Salgado:� his photos hold the mirror

of conscience up to our eyes, and as if that were not enough, he also wields an

alarming amount of macroeconomic data that makes one pall at the many

variegated forms that injustice may take.�

(For what it�s worth:� like a

writer, a photographer need not speak a single word in order to practice his

craft, but far from being mute Salgado was downright gregarious; this of course

was due to the fact that he was not practicing his craft of photographer but

rather plying his trade of fundraiser.)�

He assured us that we were living off of the work of the entire world,

of the exploited who gave us the coffee from Brazil, the cacao from Africa; and

that these people, although they did not earn nearly half as much, worked just

as hard as anyone in the audience.�

Much, much harder, I concurred,

rubbing my paunch and wondering, not without a certain amount of shame, what I

would be eating for dinner that evening.�

When Salgado was putting on his jacket with some degree of effort�he was

off to the chiropractor�s to see about his backache�I managed to timidly take

out my camera and capture him on film.

Walking home afterwards, I came upon

an ageing gypsy rooting through the garbage in front of El Arbol, one of

northern Spain�s major supermarket chains.�

I slowed my pace and observed the woman, clad in rags, hunched over a

heap of plastic bags and wooden crates, furiously tossing pieces of lettuce and

other produce over her shoulder.�

Instinctively, I reached for my camera, but I never got to remove the

lens cap:� the woman let fly a barrage

of overripe tomatoes and curses�expressing her hatred for my kind and calling

on the gods to send injury down on my wretched soul.� I took flight and was soon out of tomato range and earshot,

grateful that my survival instinct was still intact.�

Photograph by Mark Ostrowski

�

�Mark

Ostrowski (1971,