Miracle on Potsdamer Platz

by Gaither Stewart

�Where in God�s name have you been?� Petra asked as he walked in the door. �Karen has been waiting and waiting for you.�

����������� �It�s hard to explain,� Bruno said. His head was still reeling, his body anesthetized, his ears the pounding to the memory of the highways beneath him. It was the day�s bizarre unfolding. It was the vertigo. It was the road rhythm. And the lights in the night.

����������� �Try anyway,� his wife answered.

����������� �Easier to say where I�ve not been � today,� Bruno said, consciously trying to combine the disjointed words in his head into coherent expressions. The magic pill he�d taken in the car was beginning to calm him.

����������� �Just try.�

����������� �Good! If it matters! Drove to Hannover.�

�To Hannover? Why on earth there?�

�Chance. Since I was there I kept going west toward Amsterdam, and then on to the sea at Zandvoort. I wanted to see the sea.�

����������� �Zandvoort? What did you do there?�

����������� �Nothing. I just turned around and drove straight back to Haarlem � and Amsterdam ... and back to Berlin.�

����������� �That�s all? Bruno, for God�s sake, you�re mad � that must be a thousand kilometers.�

����������� �About that. I really just wanted to take a drive.�

The humming of the labyrinth of Autobahnen was still there in his ears, still in his eyes the red tail lights he passed, the crowded rows of trucks, lights flashing and blinking and flashing in the night, lights circling and flashing in the night, occasional reflections from rivers and canals, and then the rain that began falling once he reached the outskirts of Berlin. He remembered he hadn�t had the vaguest idea where he was going when he left. He just drove west. Now that it was over one thing seemed to have led to another. He�d never been to Zandvoort, had only saw the auto races there on TV. In his guts he could still feel the wildness of the dunes pushed back by the sea. Now it was like a mute film. Aimless mobs of aimless people walking around the resort town.

In his mind there were only silences.

����������� �But why? Why Bruno?� Petra cocked her head to one side and looked at him quizzically, as if she doubted his word, or his sanity.

����������� �Why? It was � it was I don�t know what. A sudden urge. An urge to go. To know how it feels. You know what I mean?�

����������� �How what feels, Bruno?�

����������� �It! I mean � nothing.�

Bruno had talked to himself all afternoon about it. He first identified the urge early afternoon just as he approached the old Dutch border. Somewhere he had stopped to observe the tankers and freighters and ferries for the islands and yachts and fishing boats and told himself he had to feel how it was to go beyond the boundary. Then later, as the road narrowed and it seemed civilization began to end, he felt he was nearing the boundary line � but it keep moving backwards. He moved forward and the boundary retreated.

��And I got to Zandvoort but everything ended there. Weeds were sprouting on the dunes. Too many people. In April! Terribly hot. So I drove back home.�

����������� �What ended there? What in heaven�s name are you talking about?�

����������� He shrugged. She thought he was lying. He asked where his daughter was. In bed, of course. Johannes too was asleep. It was nearly midnight. Johnny! His fat son whom Petra still insisted on calling Johnny. His mother had given her the idea. Johnny! He felt his usual guilt about his critical attitude toward Johannes. But his relationship with his son had never clicked. Petra�s fault�she treated the twelve-year old boy the same way she did when he was two � the same way his own mother had protected him. Johannes-Johnny, he knew, would still be under his mother�s wing when he was thirty.

����������� �She called three times this evening. She was worried.�

����������� �So what else is new?�

His mother called every evening. How were the children? How had his day gone? Were they still coming to lunch on Sunday? Of course they were going to lunch on Sunday. Didn�t they go out to Dahlem every Sunday? Things were as if complete in their perfect life. Their apartment was perfect. Their good life was guaranteed. Thanks to his mother�s intervention he was overpaid and over-promoted. They were secure for life.

Too rich, Bruno thought. We�re too rich and too spoiled. He had never considered wealth as a goal. He was born rich, lived rich, felt rich and despised it.

Telephones in their household were always busy. Petra�s ex-mother-in-law was still fixed on her and called her for advice about her wayward son who had once worked in Bruno�s company. Bruno wasn�t jealous. Also his ex-wife Ursula sometimes called to tell him or Petra or even one of the children about her new boyfriend. Johannes and Karen spoke with one and all as if they were part of a greater family. Bruno thought of it all as theater.

����������� �J�rg called too,� Petra was saying. �Luise is sick again, and apparently they�re being evicted, after 12 years in that crummy little apartment. He says they might have to move to Marzahn.�

����������� �A little bit of real life at least,� Bruno said.

Sometimes he was ashamed of their own luxury apartment on Marienstrasse in Mitte�another gift from his parents. It was big enough for several families. Ease was a keyword in their life. How could he explain such things to Petra? It was like driving an SUV on the Autobahn, so high above everything that you hardly feel the road beneath. He had begun thinking they were moving so smoothly through life that he was hardly aware he was living.

����������� �Come in the kitchen. I�ll warm your dinner.�

����������� �In a moment. I want to see Karen.�

Bruno needed to take a look at her. A strange thought had obsessed him during the silence of the night. Though thoroughly atheist and technically a Catholic, he had begun thinking that he and Petra were not real parents and givers of life to Johannes and Karen but were simply the vehicles of their conception. Maybe that was as it should be.

����������� He looked down at the sleeping child of ten and felt calm sweep over him. Her blond hair swirled around her narrow face. She looked angelic. No great resemblance to him or Petra. Yet there was her perfect nose, just like Petra�s. And there were her high cheekbones, just like his. All their genes and chromosomes were contained there. He wondered what it meant.

The next day was Saturday, the day Bruno took Karen and Johannes to the Tiergarten for ice cream when the weather was good. Today it was raining. He took another pill and set out alone. No, no umbrella. He wanted to feel the rain, to feel nature, to be part of it. There was something unheimlich about today�s rain, something warm and sticky. The pruned plane-trees were starting to bloom in the mist, reminding him of tropical rain forests. Their trunks still gray, new leaves were beginning to replace the old.

On Luisenstrasse he stopped close to a group of youths huddled near their motorbikes in front of a caf�. From their furtive looks and earnest talk you would have thought they were plotting a coup d��tat. Bruno overheard: �Nah, fuck it, I can�t, have to go to grandmother�s for lunch.� �What the fuck! Let�s do it in late afternoon then.� �Fuck, I can�t,� another voice said, �Papa wants to leave for the fucking country right after his fucking nap. A whole fucking weekend!�

����������� Bruno shrugged. The conversations of desperate Berlin youth. Dialogue of an American movie. Fuck everything! His desperate talk too. His life too.

He lifted his head and watched the rain fall. Again he tried to isolate individual drops of water, falling, falling, falling, each separate, like his own genes. Did nature too have a DNA? he wondered. He�d never been interested in science, or nature for that matter. In his world man seemed to have made everything. Now terrorism was in the air. Anti-nature at work. He felt a peculiar detachment from the terrible predictions for Easter. Bombs at St. Peter�s in Rome. High-jacked airplanes crashing into the Tour Eiffel. Nerve gas in the London metro. Somehow, Berlin seemed secure.

He crossed the Spree and stared down Wilhelmstrasse and tried to imagine it in ruins and rubble again. A cold wind blew in his face. The cold was in the soulless buildings, the cold buried deep in the concrete. Further down the boulevard, he stopped to examine again an apartment building being restructured. Completely gutted. Its life had departed.

All of a sudden it reminded him of Sabine�s grave at the cemetery in Steglitz. He stopped in his tracks. He couldn�t even pronounce the word Friedhof or Augustaplatz without tears coming to his eyes. For the first time in his life he wondered where he would be buried. Buried? In the devastation of Wilhelmstrasse and its ugly Plattenbauwohnungen and the promised bombs at St. Peter�s and gas in Europe�s metros and wildcat states with nuclear weapons, where would he be buried? Did it even matter?

Petra dwelled on their dead child, he on death. �Ridiculous death!� he murmured. �How can I live knowing I might not even be buried. What about my chromosomes then?�

Summer had arrived on the spring Sunday morning. It was an unusually hot spring or summer. The air was tropical.

Overnight Berlin had been converted into an armed camp. Sweating and swearing police and secret service men were everywhere. Surveillance cameras swept across the squares and street crossings.

Bruno, feeling guilty for his abundance, and J�rg, complaining about his poverty, were installed at their usual caf� in the Sony Center glass palace. Plastic chairs, advertising placards pressing around them, both of them eyed the eyes of the ominous black cameras slowly swinging from one side to the other of the great atrium. Palm Sunday meant nothing to either of them. Cappuccinos and brioches and small brandies were spread before them. Every table was occupied. Boys in black leather jackets and pomaded hair and girls with silver piercings in their displayed belly buttons milled around the arcades and shouted at one another and rode up and down the elevators and mobile stairs.

�Read it again, J�rg,� Bruno said, nodding toward an inscription on the crossbeam over the entrance to the Ristorante Italiano Pantheon. His friend prided himself on his Latin skills; he read it fluently and even wrote poetry in it.

�Marco Agrippa built it!� J�rg said reductively of the Latin dedication, and wiped the swath of cappuccino foam from his thin blond mustache.��

�Is that all?� Bruno said and snickered. He stretched his long legs toward the next table, ran both hands through his dark hair now speckled with gray. A strange calm had come over him. It was being with J�rg. �And what about all those tombs of the kings inside? Inside the Pantheon. What about them? �

�Lest one forget them!��

�I�ve always had an uneasy feeling about tombs of kings and dictators. The Lenin monument in Moscow sends shivers down my spine. Sometimes they want to come back.�

�They already have already come back!� J�rg pronounced, lifting his index finger like the schoolteacher he was. �Mein bester Freund, tombs exist to remind us of our own mortality. Kings or not, like all the dead, they help keep us alive � for a while yet anyway.�

�Do you think so? Tell me, J�rg, do you believe it�s really Lenin there in the mausoleum? I�ve always suspected that tombs as a rule are empty. The bodies just disappear. Maybe not even the souls endure.� Talk of tombs and departed bodies and eternal souls had become a sort of consolation for Bruno. He told himself it helped him to overcome his own nature.

He observed J�rg closely, aware that his friend�s answer would contain some unexpected truth. Something about J�rg was otherworldly. He prided himself that with his blondish hair and narrow face he looked like a foreigner�he would have liked to be at least a Dane or a Lithuanian. When they were together Bruno felt his own Germanness more�his thick hair, his too handsome healthy face, his long vitamin-enriched body, his fashionable suede jacket and cord pants his doting parents plied him with.

�That�s not the point,� J�rg said. �It�s the ritualization of death that counts. So that grief doesn�t become intolerable and destructive in the lives of the survivors.�

�Do you by chance have Petra in mind?� Bruno said, and drank off his brandy with a grimace. He didn�t like strong alcohol. He only drank it to impress J�rg.

�I�ve always thought she never really buried your Sabine,� J�rg said. �You did, you sang your dirges. She didn�t. She just suffered and continues to suffer.�

�Maybe. But you shouldn�t underestimate the impact of the loss of a child, the devastation.� Bruno knew the pain that nothing can still. It was also the solitude. Their fearful lives. Did that have something to do with genes and chromosomes? He hesitated to even think about it for fear he used Sabine as an excuse for his own shortcomings.

The Turkish waiter came back and asked if things were all right.

J�rg ordered two brandies.

Wondering if the brandy would enhance or inhibit the effect of his anti-depressive medication, Bruno added, �We have so little control over anything. How can you explain that your life suddenly reverses directions? I still divide my life into two phases�before and after her death.�

J�rg generously avoided his watery eyes and gazed toward the fake Pantheon.

�Uh, I�ve long wondered about that hole in the roof!� Bruno said. �What is it really for?� He loved talking with J�rg because he knew everything. The anti-intellectual intellectual, he always had an answer�or an opinion�some satisfactory, some bewildering, all thought-provoking.

�The hole?� J�rg said.

�In the cupola of the real Pantheon. In Rome. What�s its purpose?�

�Well, uh, it�s an eye, the only source of light inside. And it lets in the rain and the sun � falling on all the living and the dead alike. It reminds me of the layers and layers of all the dead of the world since man became man.�

�Um Gotteswillen, J�rg! How gruesome!�

�That�s our city,� J�rg said. �We have to be realistic. We�re sitting right on top of them now. On top of all our Berlin dead. Millions and millions of them. But that�s not gruesome at all � don�t forget we owe them. They�re our past. They�re progress. Actually we are our dead.�

Delicate J�rg! Sensitive. Perceptive. No false pity and commiseration there.

�But what does the Pantheon and the hole in its roof have to do with it?� Bruno said.

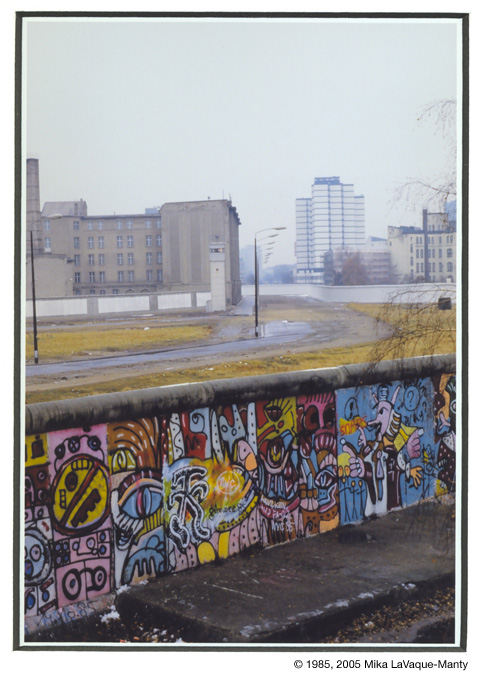

�Just building anything signals our mortality. Look at our city. Our whole city is a monument to the dead. Did you know that after the war some city planners wanted to rip up everything and start over again? We Berliners, we�re crazy and courageous. Our places, Potsdamer Platz, the Sony Center, don�t just come about naturally � we have to make them. We live in these places � these monuments � and time passes. The tombs in Rome as in our cemeteries and like all our architecture mark our place in the world, in time, in history. Our lives are founded on our places.�

After a long silence, Bruno said mysteriously: �And that�s your problem today, eh?�

�Jawohl! I need a place of my own.�

�Well, don�t worry your head any more. I spoke with my mother about it. And she has a solution � naturally. One of her friends has an available apartment for a trustworthy person like you. And you won�t believe where it is. On Marienstrasse just down the street from me! I can see us now�lunching in local restaurants and jogging in the Tiergarten.�

�I don�t know, Bruno. I�ve never liked the new Mitte much � too bourgeois. But, I have to live somewhere.�

�Place, like you said.�

�Anywhere but Marzahn!�

The weirdness was in him again. Places! Walking on our dead! On the layers and layers of our dead. J�rg forgot that half the city rested on hollow places. Great holes could open in the streets, revealing old worlds, hidden rivers running underneath, rivers like the Lethe � or was it the Styx? Everything precarious. Bruno stood at his nearly empty desk and looked out the windows onto Unter den Linden. The center of the city. Across the wide avenue was the famous hotel in which his mother had some economic interest, he�d never understood exactly what. He stared down at the correspondence the director (his Uncle Otto) had asked him to handle. What was he to do? What did he know about insurance and investments? All these years and he didn�t even know financial terminology. Or how actuarial tables worked. And he couldn�t even get fired! With all the personnel cutbacks, staff reductions, the Chancellor�s new agenda, and he couldn�t get fired. There was nothing he could do or not do to get fired. He�d been here for at least twelve years. Not long after the Wall came down. He was already here when Sabine died. It was all so absurd. J�rg�s tombs, the ritualization of death, he said. It was the absurdity of his life and the pain and the horror of death that counted.

It was Thursday before Easter. The rains had stopped. The heat held on. His mother had called to tell him she�d again seen the mother Wildschwein with her babies in their back yard. She said one got into her neighbor�s dining room and bit a guest on the leg. After all her work the wild boars were destroying her garden, she explained in her American accented German that Bruno liked�he thought it one of her most redeeming characteristics. Again she promised to stop feeding them.

While his mother went on about herself Bruno recalled how he�d hated the Dahlem villa, hated Dahlem with all its lawyers and bankers and diplomats, hated the life his parents loved and that he was ashamed of. From the time he was a teenager, escape had been his primary goal.

She finally got around to reminding him that he and the family were expected for Easter as usual at the country house in the Franken Wald. They would visit Weimar again. What else! She lived for that. After a lifetime here she was still so American. So practical, so pragmatic, so resistant to change. She would never understand his wild nature or Berliners� love for the unexpected.

Bruno called home again. Petra was still out.

He went to the big window looking out over the avenue. Near the Brandenburger Tor flocks of tourists stood with their heads tilted backwards looking at the Quadriga. Just across the flowerbeds on Pariser Platz a crowd of several hundred old people carrying placards were standing around what looked like a cardboard statue. Saint Francis in his hood, his arms raised to the sunny heavens. A row of chemical toilettes were aligned in the middle of the square.

He closed his eyes in despair that he felt no despair. �But I do feel depression,� he consoled himself. Wondering what the difference was and where exactly depression was located, he again touched his stomach as he�d been doing all morning. Everything seemed to play out in his stomach.

�The bipolar disease� his doctor called it�short maniacal phases followed by longer depressive periods�before the arrogant Prussian friend of his father�s prescribed the miraculous lamotrigina.

�Is it really in the brain?� Bruno asked himself.� �There in the hippocampus together with memory and emotions?� J�rg, who knew everything, said it was a cholin disorder�too little of that mysterious chemical substance carried men to suicide.

The sun had zeroed in on his window. Unthinking he ripped off his tie, grabbed his jacket and walked out of his office. Rette sich wer kann, he thought.

On the square he hesitated, stunned by the sudden noise. From the silence behind the double windowpanes upstairs the demonstration had seemed like pantomime. Here on the street were real people. Pensioners. Demanding their rights. They were the tail end of a great demonstration at the Rotes Rathaus. An old man carrying a placard with the inscription The crushed generation marched in circles among them. To one side, a Red Cross ambulance had its doors open and people were huddled around someone lying on the pavement.

Bruno sidled up to a makeshift stand draped with red flags where hefty organizers were handing out bananas and sandwiches. Guiltily he took a sandwich and suddenly wished he was politically committed. He could belong to one half of the nation or the other, either left or right. Didn�t matter which.

He looked straight up into the early afternoon sun. It was fiery. It seemed to hang like a threat right over the square. Half-blinded he murmured to himself, The problem is I don�t believe in anything. It was a lonely feeling. If he only belonged to something!

Fearing the onset of another maniacal phase, he took another lamotrigina and set out toward Potsdamer Platz. The sun seemed to shine brighter. Magic pills! Crazy spring. He stared unseeing at the buildings and ministries his grade school classes had visited. Heat lit on his head. Unsure which was which anymore, he grasped at reality and began repeating mechanically street names�Arendt Strasse, Hans von B�low Strasse, Voss Strasse.

By dent of habit he went into the Sony Center. He took off his jacket and wiped the sweat from his neck. He felt weakness climbing down his legs.

In front of a cinema Bruno jerked awake. The Passion of Christ! This year�s Easter film. Recommended by the Catholic Church. A beaten Christ was plastered across wall posters. His lashed body looked like a painting�everywhere a humiliated, gruesome Christ. Excess and horror. Bloody, but maybe true.�

����������� The sun still in his blinded eyes, his armpits still wet, Bruno felt his way to a seat in the back row. Was it the end or the beginning of the film? As his vision returned, they are beating Jesus. Yeoshua, they call Him. Sixty stripes the count goes. Metal hooks rip into His body. Blows and lashes and blood have blinded Him. The Roman soldiers laugh and drink wine. Blood everywhere. Blood in floods. The crowds, the scourgers, the Jews, all the sinners killing Jesus. Death to Jesus! Death to Jesus! Death to the King! Slowly. Slowly. Contained compassion on the faces of saintly persons. Did the film director want that? Mary swabbing at the lakes of His blood on the floor. Bruno felt the sun beating on his head. The blows seemed inspired. Were the blows part of divine will too? The sweat crept down from his armpits. It seemed like blood. The blood, was it salvation? He snickered.

�Get up,� he whispered as Jeoshua kept falling on his way to Golgotha. �Get up! Or aren�t You God? You wanted a bicycle,� he giggled, �now pedal.�

He felt himself blush. What should he feel, he wondered? Was his blasphemy? Was this a religious experience, the film that confused the critics and earned the praise of the Vatican? No! It was not for him. He felt neither Christian nor anti-Christian. He thought of his mother�Germanized American, a Catholic and to boot a Mischling, zweiten Grades! Her Philadelphia mother was half Jewish. He giggled. So what did that make him, Bruno Keyserling? Did God really demand the horror he was watching? Was this torture really necessary for man�s redemption? What can I honestly feel after the indoctrination of a lifetime? Bruno felt he should feel empathy for the man Jesus, for Yeoshua, but it was so weak, his empathy. He only wanted the film�s fictitious Jesus to be relieved of his suffering. Was that enough? And what about His persecutors? Bruno wanted them to stop. But which persecutors? Jews? Romans? Who were they, he wondered, his eyes again closing. Yes, it was indecent. But what relief too, he suddenly thought, to be able to hate and strike out at the world and brutalize and torture and kill. It reminded him of his morbid fascination with sadistic killers, even with serial killers, who carry their sadism to its conclusion, logical or illogical.

Bruno clamped his eyes shut, stood up, and felt his way out. Outside again on the sidewalk, the sun was back. He took one look around him and again closed his eyes. He would play blind. He would be blind.

His eyes shut, he put on his jacket. He turned right, now blind. With his hands stretched out in front of him he found the wall and started toward Unter den Linden. But no, that would be impossible to negotiate blind.

He turned on his heel and, one hand still feeling ahead of him, began retracing his steps. Cheating a bit, he cracked one eye and with pleasure noted people stepping around him and nodding their heads in compassion. Poor guy! He wished he had a Seeing Eye dog. Or at least a cane to tap on the sidewalk.

He felt the sun beating down. Again he was sweating. He took off his jacket. Blind in just one eye like Jesus after the beating was no joke. Even in a traffic free zone. Again he cracked one eye. And then, salvation!�there was a taxi stand just nearby.

����������� He opened his eyes, slid into the back seat and was closing the door, when he heard her call, �Bruno! Bruno!�

Standing beside the taxi was Laura, a pretty young woman who worked in another department of his company. In the corridors and on the great staircase he had noted her eyes linger in his several times recently. He was surprised she called him by name. They said she was French. Divorced. And anyway no male could remain immune to her long legs in such short dresses.

����������� �Back to the office?� she said in her lilting accent.

����������� �Of course not. I took the afternoon off.�

����������� �So did I.�

����������� �What about a coffee?� he said, now calming. �What about the Adlon?�

����������� �What about your taxi?� she said, her cadences and ravishing eyes seeming to confirm the rumors of her availability. �I saw you creeping toward it � as if you were blind.�

����������� Bruno laughed sheepishly. He paid the driver and stepped out beside her. The sun seemed brighter but no hotter than before. There was an air of mystery on the street outside the Sony Center, something tropical about it.

�You don�t know the half of it,� he said, telling himself to grab hold of reality and to hold on tight.

That evening they dined in the breakfast room he preferred. Petra seemed distant. Her eyes avoided his. Bruno watched her carelessly plop plates and silver down on the round table covered with a rose lace-fringed tablecloth. Johannes sulked in his chair and whined about something or other. He felt Karen staring at him. Newscasts from the small TV in the corner reported the daily horrors�fathers axing their children, children shooting their parents, school kids massacring other school kids, baby girls raped and strangled, children sold for their organs, kamikaze attacks in Jerusalem, Marines dead in Baghdad. A quiet realistic horror merged with images of the scourgers and His spouting blood passing across Bruno�s eyes.

He pushed his food around his plate and asked himself how it would�ve been if he�d gone home with Laura.

����������� �I called you at the office,� Petra said looking down at her plate. �They said you were out.�

����������� �I went to a movie,� he said, yanking at Johannes�s arm to pull him erect.

����������� �A movie?�

����������� �The Passion of Christ.�

����������� �I read that it�s disgusting,� Petra said.

����������� �Violent. Very hot.�

����������� �I didn�t know you were even interested in it � Why did you go?�

����������� �I�m not sure. Maybe it was the sun.�

����������� �The sun?�

����������� �It was so hot on Unter den Linden. I think I went in mostly to cool off.�

����������� �Did it turn into a religious experience then?� Petra said sarcastically. �Did you come away feeling redeemed?�

����������� �I came out blind.�

����������� �Blind? But now you can see. The miracle!� Petra laughed again, and looked away embarrassed.

����������� �I called you too,� Bruno said. �You weren�t in.� Not that he cared much what his wife did. Theirs had become a marriage empty of passion. He had tried to remember if there had ever been real passion. His former feelings eluded him. He supposed he was supposed to be murderously jealous but he was not.

Inshallah, he thought. If only she would have another affair!

����������� �No, the children were at their friends� house so I went downtown. I thought I saw you once, at Potsdamer Platz. You weren�t alone. But maybe it wasn�t you at all.�

����������� �Maybe not.�

Bruno hesitated. He was already beginning to lie again. He didn�t like to lie to Petra. But he felt he had to lie. When they�d both had their little affairs now years back, in the aftermath of Sabine�s death, they�d held hands in front of the marriage counselor and promised never to lie to one another again. Now he was lying. And nothing had happened except a coffee with a beautiful French woman at the Adlon. It was an anticipatory lie, he knew. In advance of events yet to come. He knew something was about to happen.

He thought in that moment that, yes, he was going to have an affair with Laura.

����������� He said, �We�re supposed to go to the Franken Wald for Easter.�

����������� �Not again!�

����������� �I want to go to Oma�s,� Johannes said petulantly. Bruno frowned at him. The fat kid was probably full of the neighbor�s sweets.

����������� �I hate going there,� Karen said. �Good for you,� Bruno thought smiling at his daughter, �when I go berserk I will spare you.�

����������� �

There�s a line out there, an invisible line you shouldn�t cross, Bruno told himself, repeating J�rg�s words first pronounced a year or so after Sabine�s death. We all want to cross the boundary. It�s alluring. It�s magnetic. It draws us all our lives but we have to resist. It�s the boundary between ordered life and chaos. The marriage counsellor also had exhorted them �to keep the boat from rocking.� He said they had to �maintain an even keel in the boat of your lives as you plow your way through life together.�

Bruno pulled into the underground garage and parked. Just to make sure, he took a pill. �Faithful and loyal lamotrigina!� With trepidation he stepped into the elevator. In his ten or twelve years here it had never stopped between floors with him. But it happened frequently with others. It was like Russian roulette, he thought and told himself that today, above all, he would keep the boat from rocking. Stay on the safe side!

Upstairs he stepped safely out of the elevator, turned right down the corridor, and there she was. �Bonjour, bonjour, �a va?�

�In that moment his life�s words flashed through his brain�places, lights blinking behind the dunes, tropical rains, summer suns, an even keel, tombs, Augusta Platz, despair, genes, lamotrigina, Wildschweine, the boundary line, the heat, the heat, blindness in the heat. He looked down at lovely Laura and wondered if there would be any difference this time.

No matter, he thought, we�re after all a crazy generation.

He took her arm and paraded her down the corridor, past the receptionists, past the secretary pool, past the cubicles of statisticians and claims coordinators, past the accounting offices.

��������� Do I really want to go on with it? he thought as he slowed provocatively just in front of the open door of Uncle Otto�s office. It was the morning overdose of the magic medicine, he thought. He was uncertain whether he was exiting depression and entering a maniacal phase or exiting a maniacal phase and returning to depression. He wondered if his depression was aggravated more by Berlin�s long winter with warm rains or by the hot spring sun and tropical rains.

Or am I just hell-bent on self-destruction? he wondered.

����������� �Ja!� he answered aloud. �Ja.�

����������� �Ja?� Laura said, stretching out the two letters into several words, then letting it rise deliciously inviting on the �a.�

�����������

Bruno rolled over in the sand, gazed absently toward the sun sinking toward the Pacific, rotated his head slowly so as to draw in every delicate ingredient of the sea breeze tickling his face, and again chuckled about his blind act on Potsdamer Platz. If he hadn�t gone blind, he wouldn�t have been in that precise place when she passed. They wouldn�t have gone to the Adlon. Most certainly he wouldn�t have announced his affaire d�amour publicly to Uncle Otto�s office.

He sat up and looked toward the town. �Zi hua ta ne ho� he syllabized the town�s name carefully. As a boy they used to say he was the only one in the family who could pronounce it. His mother said then Mexico was the only place to go in January and February. And Zihuatanejo was a hidden jewel.

Today�s town was not as he remembered it from back then. Yet, in their casita set apart from the others and a nearly private beach he and Laura hardly experienced the crowds. He had their meals brought in or they walked in the back streets of the town and ate in small restaurants. Zihuatanejo was a lonely sensation.

It was strange being here with her. Again he looked down at her. She was just beginning to tan. The first morning he�d been surprised at her washed out look without make-up. The second day her red face and the wan circles around her eyes disconcerted him even more. It was as if he hadn�t really seen her at all that day on Potsdamer Platz.

Now she sat up in the deck-chair and began gathering her creams and oils and French magazines. Her sunglasses covered half her face so that her cheeks and chin seemed to vanish. Her delicate breasts and calves were red and oily. She stood up, pulled around her a red and celeste pareo, and said she was going to shower. She would wait for him.

Bruno watched Laura walk back up the incline toward their bungalow. Her secret moment. She would now spend hours with her makeup! He knew he was being unfair but he was repelled by her too skinny legs without even a hint of hairs. Something about her reminded him of Ursula. No wonder his first marriage hadn�t lasted long. And these Parisians, he thought, all aspiring fashion models!

He smiled to himself and felt a tingle, suddenly recalling how in their first years together he�d always been turned on by the soft dark down of Petra�s thighs. And how when she forgot to shave her armpits he would caress her there.

He stood up, stepped into his clogs, threw his beach bag over his shoulder and went toward the town. Near the market place he bought a nondescript postcard with a nondescript beachfront and sat down in the park to compose an appropriate text. Even the salutation was treacherous. To whom? And with what words? Finally he wrote:

Dear Petra, Dear Karen, Dear Johannes,

The telephone lines have been out here in the town so I�m sending this by DHL. I had to make this trip but now I find it is taking less time than I believed. I can�t wait to see you again in a few days. I have to hurry back home and look for a new job.

������� Bruno Keyserling

the man from Potsdamer Platz

© Gaither Stewart

Gaither Stewart is an American expatriate journalist/writer who lives in Rome. Many of his stories and essays have appeared in Southern Cross Review and other publications.