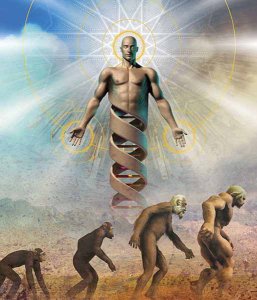

Evolution of Consciousness

From the Pre-Socratics to the Post-Moderns

Five Lectures by Keith Francis

I

Before Socrates � the Adventure Begins

New York, November 13, 2008

(i)

Introduction

One morning, a few weeks ago, my wife was looking out of the door of our cottage in Massachusetts when our local family of wild turkeys passed by. It seemed that one of them had offended the others, since they were all screaming and barking at him. We hadn�t realized that turkeys bark, but it just goes to show that you can learn something new every day � or evening. Summoned to the door to watch the proceedings, I found myself wondering about the idea of intelligent design, and feeling that somehow turkeys and intelligent design don�t seem to go together � unless the powers that be specifically intended these creatures as burnt offerings for the Thanksgiving pot. At the same time, it was difficult to imagine what strange, convoluted evolutionary path could possibly have led to such a species of ill-tempered and pathetically vulnerable individuals. However, as Shakespeare might have said, the fault is not in our turkeys (dear brutes) but in ourselves. We often talk as though there were just a simple choice between one clearly defined view and another; as though intelligent design had just one agreed meaning and evolution another � and as if these two warring notions were the only shows in town; as if we have to believe either that God created man, woman and all other living creatures as finished products or that they gradually evolved through the processes described in modern evolutionary science. This is what tends to happen when we have two sides busy defending their positions instead of trying to get at the truth. As Melissus of Samos said twenty-five hundred years ago, nothing is stronger than what is true. But truth is not always easy to find and, as Winston Churchill remarked somewhat more recently, a lie travels half-way round the world while the truth is still pulling on its pants. One approach to finding the truth, recommended by many of the world�s sages, is to look inside ourselves. There we will find both truth and lies aplenty, and even the lies tell us something truthful about ourselves.

So let me ask you to ponder something: when we look inside, do we find anything that might bear on the question of evolution? We think about all sorts of things, we have strong feelings about some of them, we make decisions and we sometimes act on them. Our physical bodies are enormously more complex than anything any of us has ever created. Everything, including our ability to think, feel and act, seems to depend on everything else. One system breaks down and our whole being is affected. We have an inner world and an outer world and, for most people, both are full of problems, but we have the potential to make an inner space where we can have peace and freedom. This is not easy to achieve and sometimes when we manage it, it feels like a victory over a hostile universe. We have high ideals but find it very hard to stop the little sins from sneaking in and selfishness from taking over. Then we have feelings of guilt, which, as far as I know, have no survival value and may help to lead us to an early grave. So if we achieve our peaceful inner space, it may be more a victory over ourselves than over the outer world. And then there is the world of nature, which is full of wonderful things and creatures and is also the scene of great suffering � �Nature red in tooth and claw�, as Tennyson called it in his great poem In Memoriam, published a few years before Charles Darwin�s Origin of Species.

According to evolutionary theory, all these amazing complexities and contradictions are the results of the accidental production and inevitable replication of long-chain molecules, and the survival values of mutations caused by such random events as the impact of a stray gamma ray. As it happens, I am a graduate in mathematics and physics from the ancient university where Darwin studied theology in the 1820�s, where J. J. Thomson discovered the electron in the 1890�s, and where Francis Crick, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins discovered or created the DNA molecule in the 1950�s, and in spite of this I find this story impossible to believe � even when an expanse of several billion years is allowed. (As we know from recent happenings in the financial world, a billion doesn�t mean as much as it used to.)

I want to emphasize, however, that to believe in the modern version of Darwinian theory is neither intellectually nor morally contemptible, and I don�t wish to give the impression that this question can be dealt with in a couple of paragraphs. Many people would argue that the fact that I don�t feel like the product of Darwinian evolution is not evidence, that it�s perfectly clear that evolution has actually taken place and that one can deny it only by suspending one�s rational faculties. One side of our human nature practically screams at us, �Yes, this is exactly the way we might expect to turn out if we are the products of biochemical trial and error, guided only by the tooth and claw of nature.� The rat race, the corporate ladder, chacun pour soi, every man for himself and the devil take the hindmost � these phrases picture a human jungle in which we trample on our competitors in pursuit of power, position, wealth and sex or even mere survival. But the other side of our nature comes to us from a completely different angle. Modern biological science has produced an impressive working model for evolution but stumbles lamely over such things as our love of music and pictures, our impulses to help perfect strangers at great cost to ourselves, and our feelings of remorse when we gratify our own desires while neglecting the needs of others. This conflict between the higher and the lower takes place inside us and we realize that here is the bit of the universe of which we have the most intimate knowledge. That�s one reason why what we think about ourselves is important. Our situation is described beautifully by the great anthropologist Loren Eiseley in his book The Man Who Saw Through Time, which is a long meditation on the work of Francis Bacon.

As a young man hunting rare, oddly shaped insects in �a rural and obscure corner of the United States,� Eiseley was overtaken by a storm on a backwoods track. �I heard�, he says, �a sudden rumble over a low plank bridge� a man high on a great load of hay was bearing down on me through the lowering dark�. The horse, in the sound and fury of the elements, appeared to be approaching at a gallop. At that moment I lifted my hand and stepped forward. The horse seemed to pause � even the rain. Then, in a bolt of light that lit the man on the hayrick, the waste of sodden countryside, and what must have been my own horror-filled countenance, the rain plunged down once more. In that momentary glimpse within the heart of the lightning, I had seen a human face of so incredible a nature as still to amaze and mystify me as to its origin. It was as if there were two faces welded vertically together along the midline�. One was lumpish with swollen and malign excrescences; the other shone in the blue light, pale ethereal and remote � a face marked by suffering, yet serene and alien to the visage with which it shared this dreadful mortal frame.� As I instinctively shrank back, the great wagon leaped and rumbled on its way� I am sure that the figure on the hayrick had raised a shielding hand to his own face� That I saw the double face of mankind in that instant I can no longer doubt. I saw man � all of us � galloping through a torrential landscape, diseased and fungoid, with that pale half-visage of nobility and despair dwarfed but serene upon a twofold countenance�. I saw, and touched a hand to my own face.�

As human beings we are part of nature and yet separate enough that we can take it as a field for thought and contemplation. But, as Eiseley says, we have not sufficiently contemplated ourselves and our otherness. �We have not realized the full terror and responsibility of existence. It is through our minds alone that the human being passes like that swaying furious rider on the hayrick, farther and more desperately into the night. He is galloping across the storm-filled heath of time, from the dark world of the natural toward some dawn he seeks beyond the horizon. Across that midnight landscape he rides with his toppling burden of despair and hope, bearing with him the beast�s face and the dream, but unable to cast off either or to believe in either. For he is man, the changeling, in whom the sense of goodness has not perished, nor an eye for some supernatural guidepost in the night.�

To Eiseley we are changelings, somehow substituted in the womb of time and nature and endowed with strange, unaccountable ideals and yearnings. But his marvellous picture fits perfectly with the idea that further back in the world�s history we came out of the spirit, lost our way in the physical world of nature and are desperately trying to find a path that will lead us home again.