By Tom Engelhardt

The Prequel: In my childhood, I played endlessly with toy soldiers

-- a crew of cowboys and bluecoats to defeat the Indians and win the West; a

bag or two of tiny olive-green plastic Marines to storm the beaches of Iwo

Jima. Alternately, I grabbed my toy six-guns, or simply picked up a suitable

stick in the park, and with friends replayed scenes from the movies of World

War II, my father's war. It was second nature to do so. No instruction was

necessary. After all, a script involving a heady version of American

triumphalism was already firmly in place not just in popular culture, but in

the ether, as it had been long before my grandfather made it to this land in

steerage in the 1890s.

My sunny fantasies of war play were intimately connected to the wars

Americans had actually fought by an elaborate mythology of American goodness

and ultimate victory. If my father tended to be silent about the war he had

taken part in, it made no difference. I already knew what he had done. I had

seen it at the movies, in comic books, and sooner or later in shows like Victory

at Sea on that new entertainment medium, television.

And when, in the 1960s, countless demonstrators from my generation went

into opposition to a brutal American war in Vietnam, they did so still garbed

in cast-off "Good War" paraphernalia -- secondhand Army jackets and

bombardier coats -- or they formed themselves into "tribes" and

turned goodness and victory over to the former enemies in their childhood war

stories. They transformed the V for Victory into a peace sign and made

themselves into beings recognizable from thousands of westerns. They wore the

Pancho Villa mustache, sombrero, and serape, or the Native American headband

and moccasins. They painted their faces and grew long hair in the manner of

the formerly "savage" foe, and smoked the peace (now, hash) pipe.

American mytho-history, even when turned upside down, was deeply embedded

in their lives. How could they have known that they would be its undertakers,

that their six-shooters would become eBayable relics?

You can bet on one thing today: in those streets, fields, parks, or rooms,

children in significant numbers are not playing G.I. versus Sunni insurgent,

or Special Op soldier versus Taliban fighter; and if those kids are wielding

toy guns, they're not replicas from the current arsenal, but flashingly neon

weaponry from some fantasy future.

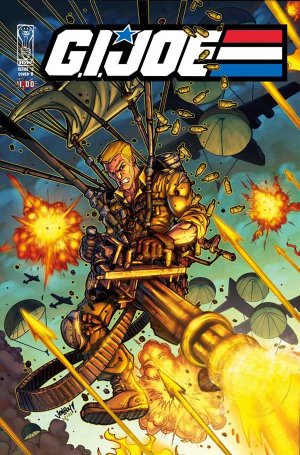

As it happens, G.I. Joe -- then dubbed a "real American hero" --

proved to be my introduction to this new world of child's war play. I had, of

course, grown up years too early for the original G.I. Joe (b. 1964), but one

spring in the mid-1980s, during his second heyday, I paid a journalistic

visit to the Toy Fair, a yearly industry bash for toy-store buyers held in

New York City.

Hasbro, which produced the popular G.I. Joe action figures, was one of the

Big Two in the toy business. Mattel, the maker of Joe's original inspiration

and big sister, Barbie, was the other. Hasbro had its own building and, on

arriving, I soon found myself being led by a company minder through a

labyrinthine exhibit hall in the deeply gender segregated world of toys.

Featured were blond models dressed in white holding baby dolls and fashion

dolls of every imaginable sort, set against an environment done up in nothing

but pink and robin's egg blue.

Here, the hum of the world seemed to lower to a selling hush, a baby-doll

whisper, but somewhere off in the distance, you could faintly hear the

high-pitched whistle of an incoming mortar round amid brief bursts of

machine-gun fire. And then, suddenly, you stepped across a threshold and out

of a world of pastels into a kingdom of darkness, of netting and camouflage,

of blasting music and a soundtrack of destruction, as well-muscled male

models in camo performed battle routines while displaying the upcoming line

of little G.I. Joe action figures or their evil Cobra counterparts.

It was energizing. It was electric. If you were a toy buyer you wanted in.

You wanted Joe, then the rage in the boy's world of war play, as well as on

children's TV where an animated series of syndicated half-hour shows was

nothing but a toy commercial. I was as riveted as any buyer and yet the world

I had just been plunged into seemed alien. These figures bore no relation to

my toy soldiers. On first sight, it was hard even to tell the good guys from

the bad guys or to figure out who was fighting whom, where, and for what reason.

And that, it turned out, was just the beginning.

The Sequel (August 2009): Nobody's mentioned it, but the most

impressive thing about the new movie, G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra,

comes last -- the eight minutes or so of credits which make it clear that, to

produce a twenty-first century shoot-em-up, you need to mobilize a veritable army of

experts. There may be more "compositors" than actors and more movie

units (Prague Unit, Prague Second Unit, Paris Unit) than units of Joes.

As the movie theater empties, those credits still scroll inexorably

onward, like a beachhead in eternity, the very eternity in American cultural

life that G.I. Joe already seems to inhabit. The credits do, of course,

finally end -- and on a note of gratitude that, almost uniquely in the film,

evokes an actual history. "The producers also wish to thank the

following," it says, and the list that follows is headed by the

Department of Defense, which has been "advising" Hollywood on how

to make war movies -- with generous loans of equipment, troops, consultants,

and weaponry in return for script "supervision" -- since the silent era.

Undead Joe

Think of G.I. Joe as a modern American zombie. "He" may never

have existed, but he just won't die. More on that later.

As a start, I'm sure you want to know about the new Joe movie which was

meant, like Star Trek earlier

in the summer, to reinvigorate a semi-comatose brand by retelling its

ur-story. In the process, the hope is to create a prequel to endless sequels

that, like the Transformers

series (also from a

toy that was an eighties hit), will prove to be Hollywood's Holy Grail of

endless summer, bringing in global mega-profits forever after.

I caught G.I. Joe, the Rise of Cobra, one

sunny afternoon in a multiplex theater empty of customers except for a few

clusters of teenage boys. So where to start? How about with the Joes'

futuristic military base, all flashing screens, hi-tech weaponry, and next

generation surveillance equipment, built under the Egyptian desert. (How this

most postmodern of bases got under Pharaonic sands or what kind of Status of

Forces Agreement the Joes have with the government of Egypt are not questions

this film considers.) But here's the thing: well-protected as the base is,

spectacularly armed and trained as the Joes are, it turns out to be a snap to

break into -- if you happen to be a dame in the black

cat suit of a dominatrix and a ninja dressed

in white.

And then there's that even spiffier ultra-evil base under the Arctic ice

(a location only slightly less busy than Times Square in movies like this).

It's the sort of set-up that would have made Captain Nemo salivate.

Oh, and don't let me forget the introductory scene about a Scottish arms

dealer in seventeenth century France condemned to having a molten mask fitted

over his face for selling weapons to all sides -- and his

great-great-great-something-or-other who's doing the same thing in our world.

Then there are those weaponized exoskeletons lifted from Iron Man

(which also had its own two-faced arms dealer), the X-wing-fighter-style

space battle from Star Wars but transposed under the ocean (� la James

Bond in Thunderball),

not to speak of the Bond-ish scene in which the evildoer, having captured the

hero, introduces him to a fate so much worse than death and so time-consuming

it can't possibly work.

And how can there not be a scene in which a famous landmark (in this case,

the Eiffel Tower) is destroyed by the forces of evil, collapsing on panicked

crowds below -- as in Independence Day or just about any disaster film

you'd care to mention? Throw in the sort of car chase introduced a zillion

years ago in Bullitt,

but now pumped up beyond all recognition, and, oh yes, there's someone who

wants to control the world and will do anything, including killing millions,

to achieve his purpose (ha-ha-ha!).

Is that clear enough? If not, it doesn't matter in the least. Movies like

this are Hollywood's version of recombinant DNA. They can be written in the

dark or, as in the case of this film, in a terrible

hurry because of an impending writers' strike. All that matters is that

they deliver the chases and explosions, the fake blood and weird experiments,

the wild weaponry and futuristic sets, the madmen and heroes at such a pace

and decibel level that your nervous system is brought fully to life jangling like

a fire alarm.

These, today, are the son et lumi�re of American youthful screen

life. Their sole raison d'�tre is to deliver boys and young men -- and

so the franchise -- to studios like Paramount (and, in cases like Joe, to the

Department of Defense as well): the Batman franchise, the Bond franchise, the

Terminator franchise, the X-Men franchise, the Bourne franchise, the Iron Man franchise, the

Transformers franchise. And now -- if it works -- the G.I. Joe franchise.

After all, the first word that appears on screen without explanation in

this latest junior epic is, appropriately enough, Hasbro. We're talking about

the toy company that is G.I. Joe and, in a synergistic fury, is just

now releasing an endless range of toys (G.I.

Joe Rise of Cobra Night Raven with Air-Viper v1), action figures,

video

games, board

games, Burger

King give-aways, and who knows what else as synergistic accompaniments to

this elaborate "advertainment."

Barbie's Little Brother

Hasbro first brought Joe to market in 1964. He was then 12 inches tall and

essentially a Barbie for boys, a soldier doll you could dress in that

"Ike" jacket with the red scarf or a "beachhead assault

fatigue shirt," then undress, and take into that pup tent with you for

the night.

Of course, nobody could say such a thing. Officially, the doll was

declared a "poseable action figure for boys," and that phrase,

"action figure," for a new boy toy, like Joe himself, never went

away. He had no "backstory" (a word still to be invented), and no

name. (G.I. -- for "Government Issue" -- Joe was a generic term for

an American foot soldier, redolent of the last American war in which total

victory had been possible.) Nor did he have an enemy, in part because young

boys still knew a version of American history, of World War II and the Cold

War. They still knew who the enemy was without a backstory or a guide book.

Though born on the cusp of the Vietnam War, Joe prospered for almost a

decade until antiwar sentiment began to turn war toys into the personae

non gratae of the toy world and, in 1973, the first oil crunch hit,

making the 12-inch Joe far more expensive to produce. First, he shrank and

then, like so many of his warring kin, he was (as Hasbro put it)

"furloughed." He left the scene, in part a casualty, like much of

war play then, of Vietnam distaste and of an American victory that never

came.

Despite being in his grave for a number of years, as the undead of the toy

world he would rise again. In 1977, paving the way for his return, George

Lucas brought the war flick and war play back into the child's world via the

surprise hit Star Wars and its accompanying 3�-inch high action

figures that landed on Earth with an enormous commercial bang. Between them,

they introduced the child to a self-enclosed world of play (in a galaxy

"far, far away") shorn of Vietnam's defeat.

In 1982, seeing an opening, Hasbro's planners tagged Joe "a real

American hero" (which once wouldn't have had to be spelled out), and

reintroduced him as a set of Star-Wars-sized action figures, each with its

own little bio/backstory. Hundreds of millions of these would subsequently be

sold. The Joe team now had an enemy as well, another team, of course, and in

this case, though the Cold War was still going full blast in those early

years of Ronald Reagan's presidency, it wasn't the Russians.

As it happened, Hasbro's toymakers did a better job of predicting the

direction of the Cold War than the CIA or the rest of our government. They

sensed that the Russians wouldn't last and so chose a vaguer, more

potentially long-lasting enemy -- and in this, too, they were prescient. That

enemy was a bogeyman called "terrorism" embodied in Cobra, an

organization of super-bad guys who lived not in Moscow, but in -- gasp --

Springfield, U.S.A. (Hasbro researchers had discovered that a Springfield

existed in every state except Rhode Island, where the company was located.)

In story and style, the Joes and their enemies now left history and the

battlefields of this planet behind for some alternate Earth. There, they

disported themselves with bulked-up weaponry and a look that befitted not so

much "real American heroes" as a set of superheroes and

supervillains in any futuristic space epic. And so, catching the zeitgeist

of their moment, at a child's level, the crew at Hasbro created the most

successful boy's toy of that era by divorcing war play from war

American-style.

The Next War, On-Screen and Off

Twenty-seven years later, Joe, who lost his luster a second time in the

1990s but never quite left the toy scene, is back yet again with his new

movie and assorted products. Whether this iteration proves to be another

lucrative round for the franchise depends not just on whether enough American

boys turn out to see him, but on whether his version of explosive action, special

effects, and up-muscled futuristic conflict is beloved by Saudis, Poles,

Indians, and Japanese. Today, for Hollywood, when it comes to shoot-em-ups,

the international market means everything.

Abroad, G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra opened

smashingly in South Korea and, in its first week, hit number one in

less-than-all-American China and Russia as well. It took in nearly

$100 million overseas in its first 12 days, putting its U.S. take in the

shade. Here, it started strong, but fell

off quickly in a deluge of terrible reviews.

Whatever

his fate, Joe, we know, can't die. On the other hand, that all-American tale

of battle triumph shows little sign of revival. Admittedly, the new G.I. Joe

movie does mention NATO in passing and one member of Joe's force is said,

again in passing, to have been stationed in Afghanistan. In addition, the

evil arms maker's company produces its super-weapons in that obscure but

perfectly real former Soviet SSR, Kyrgyzstan, where the U.S. rents

out a base to support its Afghan War activities. Otherwise, the film's

only link with real world battlefields comes from those borrowed Pentagon

Apache helicopters and Humvees -- and the fact that some of the military

extras lent by the Pentagon have been unable to see the film because they're now

stationed in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Whatever

his fate, Joe, we know, can't die. On the other hand, that all-American tale

of battle triumph shows little sign of revival. Admittedly, the new G.I. Joe

movie does mention NATO in passing and one member of Joe's force is said,

again in passing, to have been stationed in Afghanistan. In addition, the

evil arms maker's company produces its super-weapons in that obscure but

perfectly real former Soviet SSR, Kyrgyzstan, where the U.S. rents

out a base to support its Afghan War activities. Otherwise, the film's

only link with real world battlefields comes from those borrowed Pentagon

Apache helicopters and Humvees -- and the fact that some of the military

extras lent by the Pentagon have been unable to see the film because they're now

stationed in Iraq or Afghanistan.

And did I even mention that those missiles around which the movie's plot

(such as it is) revolves are filled with "nanomites,"

supermicroscopic, potentially world destructive robots? Whether blasting into

the Eiffel Tower or a bus, they produce a signature green fuzz that looks

like a potentially useful replacement for Styrofoam. Anyway, nanomites,

typically enough, are not yet on this Earth.

Soon after the film begins, a caption announces, Star Wars-style, that

we're "in the not too distant future," and immediately you know

that you're in Hollywood's comfort zone, a recognizable battle landscape that

is no part of what once would have been the war movie. Also recognizable is

that loaned Pentagon equipment and the fantasy weaponry mixed seamlessly in

with it -- "That's

a Night Raven!" -- that make the film "advertainment" as

well for the techno-coolness of the U.S. military. The Pentagon, you might

say, is perfectly willing to make do with post-historical battle space. It

may be ever less all-American, but it's where the recruitable young are

heading.

For Hollywood, deserting actual American battlefields isn't the liberal

thing to do, it's the business thing to do. In fact, those planning out the

film for Hasbro and Paramount reportedly wanted to transform the Joes into an

international

special ops force based in Belgium,

where NATO is headquartered. However, fan grumbling at the early teasers

Paramount released for the film (and evidently a Pentagon reluctance to help

a less than American force) caused them to pull back somewhat.

Still, one thing is certain: if the American car has gone to hell,

Hollywood's products still rule the globe. And yet, in that international

arena, American-style war, as in Iraq or Afghanistan, is a complete turn-off

and real-world all-American triumph just doesn't fly any more. That's certainly

part of what's happened to the American war film, but far from all of it.

After all, how long has it been since all-American mythology and imagery

-- the bluecoats' charge, the Marines' advance (as the Marine hymn wells up

in the background) -- has brought a mass audience to a movie screen. The last

such film, in 1998, was Saving Private Ryan, and it was already an

anomaly. Today, as close as it gets is the parallel universe that passes for

World War II in Quentin Tarantino's new hit Inglourious Basterds.

So here's something to contemplate in the moments of lame dialogue that

lurk between Joe's explosions and chases: American audiences seem largely in

accord with the international crowd. They may not want their Joe force

stationed in Belgium, but they don't want to see real war American-style on a

recognizable planet Earth either. They voted with their feet most recently on

a bevy of Iraq films.

Given the couple of hundred years that made triumphalism a kind of

American sacrament, it's nothing short of remarkable that the young are no

longer willing to troop to movie theaters to see such films. If you think of

Hollywood as a kind of crude commercial democracy, then consider this a

popular measure of imperial overstretch or the decline of the globe's sole superpower.

Only recently has a mainstream discussion of American decline begun in

Washington and among the pundits. But at the movies it's been going on for a

long, long time.

It's as if the grim reality of our seemingly never-ending wars seeped into

the pores of a nation that no longer really believes victory is our due, or

that American soldiers will triumph forever and a day. There may even be an

unacknowledged element of shame in all this. At least there is now a

consensus that we fight wars not fit for entertainment.

As a result, war as entertainment has been sent offshore -- like

imprisonment and punishment. Hollywood has launched it into a netherworld of

aliens, superheroes, and robots. Something indelibly American, close to a

national religion, has gone through the wormhole and is unlikely to return.

Joe lives. So does war, American-style -- the brutal, real thing in

Afghanistan and Iraq, at Guantanamo and Bagram, in the Predator and Reaper-filled

skies over the Pakistani tribal borderlands, among Blackwater's

mercenaries and the tens of thousands of private, Pentagon-hired military

contractors who now outnumber

U.S. troops in Afghanistan. But the two of them no longer have much to do

with each other.

If the Chinese, and South Koreans, and Saudis, and enough American young

men vote with their feet and their wallets, there will be another Joe film. And

if Washington's national security managers have anything to say about it,

there will be what's already regularly

referred to as "the next war." Film and war, however, are

likely to share little other than some snazzy weaponry, thanks to the

generosity of the Department of Defense, and American kids who will pay good

money to sit in the dark and then perhaps join up to fight in the

all-too-real world.

Succeed or fail, the screen version of G.I. Joe is now the new normal.

Succeed or fail, the war in Afghanistan is also the new normal.

In this way, an entertainment era ends. The curtain has come down and the

children have gone off elsewhere to play; meanwhile, behind that curtain --

Americans would prefer not to know just where -- you can still faintly hear

the whistle of incoming mortars, the rat-a-rat of machine guns, the sounds of

actual war that go on and on and on.

Tom Engelhardt, co-founder of the American Empire Project,

runs the Nation Institute's TomDispatch.com. He is the author of The

End of Victory Culture, a history of the Cold War and beyond, as well as

of a novel, The

Last Days of Publishing. He also edited The

World According to TomDispatch: America in the New Age of Empire (Verso,

2008), an alternative history of the mad Bush years.

[Note for further reading: In my book, The

End of Victory Culture, G.I. Joe is a major character, along with the

comic books, films, toys, and TV shows, as well as the politics and wars of

the last half century-plus. If you want to know more about how the American

century was truncated years early in popular culture, or read a history of

the collapse of American triumphalism (and its brief launch-crash-and-burn

revival in the Bush era), then do check it out -- or to read comments on it,

reviews of it, and excerpts from it, click here. Here's what Studs

Terkel said about the first edition of the book (since updated to include the

Bush years): "America Victorious has been our country's postulate since

its birth. Tom Engelhardt, with a burning clarity, recounts the end of this

fantasy, from the split atom to Vietnam. It begins at our dawn's early light

and ends with the twilight's last gleaming. It is as powerful as a Joe Louis

jab to the solar plexus."]

Copyright 2009 Tom Engelhardt

This article originally appeared in TomDispatch.com

Home