The Great Men of Samos

by Paul Holler

On a bright blue evening some days ago, I was walking down the road between the agora and my house when I saw a line of men on horseback riding toward me.� I�d been walking a long time, drawing my cart behind me.� It had been a slow day at the agora and my cart was heavy with all of the goods I did not sell.� I set my cart alongside the road and sat down to rest.� As the men on horseback came nearer, I was drawn to the man on the finest horse. He sat easily while his men trotted behind him.� I looked up to him and raised my hand.

����������� �I know you,� I said, �You were once a slave.� You are Paulus.� You belonged to Alexandros�s house.�

����������� �I belong only to my King,� he said and slashed the air with his hand.� Then he turned to his men and jerked his head toward the house in the distance and the ground shook with their horses� hoof beats.

����������� I pulled my cart back onto the road and set out for home.� While I was walking, I could not stop thinking about Paulus.� I never thought I�d see him on so fine a horse and dressed in a rich man�s robe.� Yet, there he was.

����������� The taverna lay ahead of me.� The great men of Samos were gathered there, as they were every evening.� I decided to pay them a visit.

The great men of Samos are very much like me; white haired with wisdom and great with the fruits of a good life.� Not content with the fruits, we are also great with the bread, cheese, wine and lamb of a good life.� Such is our greatness that we fill twice the space of the taverna as men half our age.�

I pulled up a chair and called for the serving girl to bring me a retsina.� The great men sat around the table, flipping their kolomboi, playing backgammon and expounding their truths.� I told them about my meeting Paulus on the road outside of town.

����������� �Alexandros died some years ago,� said the great Cleatus.� �On his deathbed, he gave all of his slaves their freedom.� Alexandros was a good man after all.� And Paulus?� He is landowner himself now.� I understand he is a very great man.� He has slaves of his own now but I understand he treats them well.�

����������� �Landowner?� Bah!� said the great Themistocles.� �I heard that he works his own land alongside his own slaves. What kind of a landowner works his own land?�

����������� �Oh, his house will never be as great as Alexandros�s house,� said the great Darius.� �Paulus� house is very small.� He only has a few slaves.� I don�t think he has the ambition to be a great man.� He will be forgotten.�

����������� �You are wrong about that, Darius,� I said.

����������� �Bah! Nonsense!� What has he ever done that any Samian would remember?�

����������� �You would have to ask Aesopus that question.�

����������� �Aesopus?� You mean the slave Aesopus?� The cripple who talked like a barbarian?� Besides, wasn�t he killed some years ago?�

����������� �Yes, he was.� But in life he could make words,� I said.� �He made words that people remember to this day.� I certainly do.��

����������� �How true that is, even if I said it myself.� Yes, Aesopus worked very hard to make his words understood.� He had to overcome his own gnarled tongue and the derision of his betters.� But a vine that fights for water produces the finest grapes.�� Likewise, when Aesopus fought to bring out his words, no one who heard them ever forgot them.���

I wonder what Aesopus would say if he could see Paulus now.� It�s hard to know.� But Aesopus was there to witness the moment of Paulus� greatness.� Or maybe it was Aesopus who gave him that moment.� I happen to know that he never forgot what he saw that day.� I was there, too, and I remember it well.�

I had arrived at the agora at my usual time that day, set out the same goods to sell as I had the day before and set the same foolishly high price for them.� I made the same bargains as I did every day.� The slaves filed past me as they always did. I paid no more attention to them than I would have to a stream of ants wearing a path in the ground.��

Nothing had changed at the agora except that, on that day, I noticed Aesopus.�� I�m not sure why I noticed him.� I saw him at the agora almost every day.� It could have been the mere fact that there was no reason to notice him that made it impossible to turn him a blind eye.� I don�t know.� But that day, I saw that he was not in line with other slaves.� He sat to the side of the path, watching the slaves file into the market while Alexandros, the man who gave them all a living in exchange for their lives, sat astride a fine horse being led by one of their own.�

����������� I had often wondered what Aesopus did to earn his keep.� He belonged to Xanthus, who was known to be a learned man.� Aesopus often roamed the agora by himself, the only slave I knew of who was so privileged.� I don't recall ever seeing Aesopus working with the others.� Sometimes he fetched and carried for Xanthus but more often he sat alongside the other slaves, watching them with onyx eyes and listening with the intensity of Homer.� I suppose there was not much more he could have done.� He was neither a large nor a strong man and his shoulder was bent to a strange angle.� When he spoke, he had trouble making words. Sometimes he seemed pitiable and he brought out the generosity in people.� At other times, he seemed the xenos and brought out their fear.� Either way, it couldn't have been an easy life.

����������� I stood and watched Aesopus who watched the other slaves with a furrowed brow.� The slave who had been leading Alexandros�s horse stopped, tied the horse to a tree and helped his master dismount.� Alexandros stood up straight, shoved the slave out of his way, shook the stiffness out of his bottom and dusted off his cloak.� He rested his hands on his hips, looked around him and began stroking his beard with his fingers.

����������� �Where�s Paulus?� said Alexandros.� �He�s supposed to be here to round up the others.�

����������� The slave looked down at the ground and folded his hands in front of him.� �I don�t know where he is, Sir.�

����������� �Well go find him!� Alexandros barked.� �He�s supposed to be here.�

����������� The slave trotted away and disappeared into the crowd.� Alexandros shaded his eyes with his hand and looked across the agora.� He raised his head when he saw Paulus.

����������� �Paulus!� he shouted, walking toward the slave.� �I want you here now!�

����������� Paulus walked toward his master calmly, even serenely.� Without a word, he stood before Alexandros with an expectant look.

����������� �Where�ve you been?� said Alexandros impatiently. �I needed you and I couldn�t find you again!�

����������� �Here I am.� said Paulus quietly.

����������� �One of these days,� said Alexandros wagging his finger, �one of these days, Paulus, you�ll go too far!� Who are you to think you can wander off by yourself?� You think you have a mind of your own, but let me tell you, I own you and your mind!�

����������� It was then I noticed that Alexandros was acquiring an audience.� It wasn�t a very large audience, to be sure, but it was an attentive one.� Aesopus had circled around the two men and taken a position at their side, behind a few other men who were setting up their stalls.� Another man, Lykourgos, a wealthy merchant who had come to trade in fine gold work, stood nearby.

����������� �You�ve got a problem on your hands,� said Lykourgos, laughing.� �If you have to tell your slave you own him, do you really own him?�

����������� �Oh, I let you talk too much, Lykourgos.�

����������� �Do you?�

����������� �Yes, I do.� My slaves do my bidding.� Nothing more, nothing less.�

����������� �So, by wandering off into the crowd, as if he had nothing to do and no one to serve, he is doing your bidding?�

����������� Alexandros turned to Paulus.� �Do you see what you�ve done?� he said, exasperated.� �You are making a fool of me!� After all I�ve done for you, I�ve given you a home, I�ve provided you with honest work and this is how you repay me!�

����������� Paulus� expression did not change.

�Have I not repaid you with my work?� he said.

����������� �You owe me much more than your work, young Paulus!� Alexandros shouted.� �You belong to my house!� When I come home, I expect the dogs to celebrate my return, the horses and donkeys to rear up in their stalls in joy at seeing their master!� But you?� What do you show me but disrespect?� Just remember, you are a slave.� And you are one of many.�

����������� Paulus considered that for a moment.�

����������� �I am.� he said. �As are you.�

����������� �As I am what?� Alexandros asked impatiently.

����������� �You are a powerful man.� And you are one of many.�

����������� �And you are replaceable!� said Alexandros, stabbing the air with his finger.

����������� �Oh, you�re in trouble now.� said Lykourgos.

����������� �Stay out of matters that don�t concern you!� barked Alexandros.

����������� �Oh, come now,� said Lykourgos, draping his arms around Alexandros�s shoulder,� �don�t be so defensive.� You know, you have a good man here.� Whether he respects you or not, he has a mind.� He has spirit, in his own, odd way.� Yes, he�s a good man.� Maybe not a good slave, but a good man.�

����������� �Spirit I don�t need.� said Alexandros. �I don�t even need a man with a mind.� I need a man with a strong back and a respect for his betters.� That�s what I need.�

����������� �Is that what you are, Paulus?� said Lykourgos.� �Are you a man with a mind and a destiny that you have chosen?�

����������� �I have a destiny.� I have a mind,� said Paulus.� �Just as you do.� Even the gods and the hares that they hunt have minds and destinies.��

����������� �You know, if you were my slave, you would not be looking me with those empty eyes that you save for Alexandros here.� With him you can just stand there, let the world do what it will and come up with pretty words to explain it away.� But my slaves either look at me with terror in their eyes or murder in their hearts.� Either way is to my liking.� If you were my slave, you would learn that.�

����������� Alexandros stood beside Lykourgos, studying his eyes.� Aesopus also stood by, closer now, watching.

����������� �Hmmm�� said Alexandros.� �You seem to have a proposition in mind.�

����������� �Oh, perhaps.� Perhaps.� But then again, perhaps not.�

����������� �Oh, come now.� I�ve known you a long time, Lykourgos.� I know when you want to strike a bargain and you want to strike a bargain.�

����������� �I do not need any more slaves.� I have enough to suit my needs.� Any more would be a burden to me.�

����������� �Really?� said Alexandros.

����������� �Well, I don�t know what I would do with this one,� said Lykourgos.

����������� �Is that so?�

����������� �Why do you think you know what is in my mind?� If you want to sell your slave, go find yourself someone who wants to buy one.�

����������� �I never said anything about selling my slave.� said Alexandros.� �But that was in your mind, wasn�t it?�

����������� �Sometimes I really let you talk too much!�

����������� �So why don�t you do some of the talking?�

����������� Lykourgos looked deeply into Paulus� eyes.�

����������� �I just might,� he said.� �I just might.�

����������� Lykourgos smiled and then began to laugh.� Something in the way he laughed made Aesopus shrink back.

����������� �Well, slave with a mind of his own, how would you like to become a part of my retinue?�

����������� Paulus said nothing.

����������� �Oh, come now.� We all know you have strong opinions for a slave.� If you could choose the man who owned you, who would it be?� Alexandros?� Lykourgos?� Perhaps the great Zeus himself?�

����������� �It wouldn�t matter.� My lot would be the same no matter who owned my hands and feet.�

����������� Alexandros looked at Paulus and shook his head.�

����������� �Would it, Paulus?� asked Alexandros.� �If I sold you to Lykourgos today, I would have a pocketful of Drachmae and you would be a sorry slave.� Lykourgos would work you like an animal and beat you whenever he pleased.�

����������� �You work me like an animal.� said Alexandros.� �You beat me, too.�

����������� �He has you there, Alexandros,� said Lykourgos quickly.� �Am I really so inhuman compared to you?�

����������� Alexandros did not answer, but turned to Paulus.� �You would appreciate the home you have with me if you spent one night under the roof of this man.� He treats his slaves far worse than I treat you.�

����������� �Have you ever been his slave?� Paulus asked.

����������� �I�ve never been the slave of any man!�

����������� �Can you be sure that his slaves have so different a lot than yours?�

����������� �I can be sure,� said Alexandros, with a growl in his voice.� �Surer than you�ll ever know.� Maybe I should sell you to him and then you�ll find out once and for all that I am a better master than he is!�

����������� �That is an excellent idea,� said Lykourgos.� �I�ll take this troublemaker off your hands.� I�ll turn him into useful being.�

����������� �Well, what do you think of that?� said Alexandros to Paulus.� �I just may sell you to this man.� What do you think of that?�

����������� �I think nothing about it at all.� said Paulus.� �Whether I belong to you or this man, I am still a slave.�

����������� �Then why shouldn�t I sell you to this man!�

����������� Paulus said nothing.

����������� �Let�s not waste any more time,� said Lykourgos.� �I�ll give you 75 drachmae for him.�

����������� �75 drachmae! What do you take me for, a mere child in the woods?� I would take nothing less than 125 drachmae.�

����������� �Oh, come now.� You know very well that no slave is worth 125 drachmae.�

����������� �I know that very well?� I know very well that a slave of his youth and strength is worth twice that.�

����������� �Then why aren�t you asking for twice that?�

����������� �What do you offer for him?������������ �75 drachmae.� My offer stands.� And remember, I�m taking him because he is a burden to you.�

����������� �I wouldn�t take a mere 75 drachmae for a dog much less a slave of this quality.� He was a soldier once.� He knows things and has seen things you can�t imagine.� 100 drachmae.�

����������� Lykourgos pursed his lips and thought.

����������� �Very well.� he said.� �100 Drachmae it is.�

����������� �Paulus, go.� said Alexandros, motioning the slave toward Lykourgos.

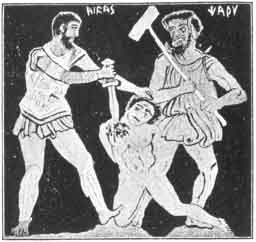

����������� Without a word or even a stern look, Lykourgos took hold of the slave�s arm and pulled him to the side.� It was all Paulus could do to keep his balance.� Aesopus drew closer, but still stayed lost in the crowd.�� With one hand, Lykourgos kept an iron grip on Paulus� arm.� With the other, he reached into a sack slung over the shoulder of one of his other slaves and drew out a long leather cord.� Clasping Paulus� wrists, he tied them together with the cord, the last round so tight it made the slave wince. Alexandros dropped his jaw.� Aesopus stepped back as though his hands were being tied.� Then Lykourgos knelt down and, with another leather cord, tied Paulus ankles together.� Something in Lykourgos had changed.� He seemed a different man: a new, terrible and deadly serious man.

����������� �On your knees, slave.� said Lykourgos.

����������� Paulus complied without a word, a look or a gesture other than the bending of his knees.� Alexandros began to speak, but changed his mind and remained silent.

����������� �You are wrong, my slave.� said Lykourgos.� �It does matter whose burden you carry.� I expect absolute obedience from my servants.� Remember that your very life is in my hands.� And if you use that same sharp tongue with me that you do with Alexandros, I�ll kill you.� You are my property.� You�re life is mine.�

����������� Paulus stared at the ground.

����������� �Look at me.� said Lykourgos.� Paulus turned his head slowly.

����������� �I said look at me!� cried Lykourgos, kicking Paulus hard in the ribs.����������� Air burst from Paulus� lungs and he fell over on his side.�

����������� �Get up!� he shouted.� Paulus tried, but with his hands and feet bound, he could only struggle on the ground.

����������� �I said get up!� cried Lykourgos again, this time grabbing Paulus by the hair and sitting him upright.�� �When I tell you to kneel, you will kneel!� When I tell you to get up, you will get up!�

����������� Then, Lykourgos reached for a wooden axe handle that he kept close by and drew it back.� Paulus closed his eyes and clenched his teeth.

����������� �Enough!� cried Alexandros, snatching the axe handle from Lykourgos� hand.� �He was trying to do what you said!� You�re going to give him a beating because you�re not letting him do what you say!� What kind of a man does that?�

����������� �This isn�t any of your affair any longer, Alexandros.� He�s a slave.� And furthermore, he�s my slave.�

����������� �No he isn�t.� cried Alexandros.� �He�s my slave, not yours.� You haven�t paid me for him.�

����������� �Very well.� said Lykourgos, turning to his man.� �Pay the man.�

����������� �Never mind.� said Alexandros.� �He�s not for sale.�

����������� Alexandros drew out a knife, got down on his knees and cut the binds on Paulus�s hands and feet.

����������� �You�re making a big mistake, Alexandros.�� said Lykourgos.� �You�ll never be able to control your slaves now.�

����������� �I can control my slaves.� And I�ll not be controlled by anyone.� Not them.� Not you.�

����������� Lykourgos laughed cruelly, then turned and walked away.

����������� That evening, I was walking home along the main road when I saw a small crowd gathered around a fire.� I stopped to rest and to see what had them all so interested.� Aesopus stood before them, silent and infinitely patient.� The talk of the crowd had become a part of the woods around us.� After a while, I could not tell the sound of their talk from the chirping of the crickets, the click of the bats and the rush of wind through the trees.

����������� I was beginning to think that Aesopus was being lulled by all of this.� I certainly was.� I wanted only to find a soft spot in the ground and go to sleep.� But then Aesopus drew himself up before the crowd and, suddenly, strangely, he was no longer seemed so odd.� His back seemed straighter somehow and his bearing larger.�� His eyes, so often averted, now burned bright and met the crowd�s eyes.� The talking stopped.� The crickets� chirping faded.� The wind relented.� Aesopus stood over the crowd, waiting for his time.

����������� After the fire had gone down to glowing embers, he began to speak.

����������� �You talk about slavery and what it is for a man to own the life of another man?� he said, taking a deep breath and letting it out very slowly.� �I say that I can do that better than anyone, even the great Solon.� Who better to tell you what it is to be owned by another man than someone who is owned by another man?

�Does it really matter who owns you?� If it is your lot to be owned by someone, be it a landowner, a king or a general, are you not the same as any man whose life belongs to another man?� Or, does it really matter who owns you?�

����������� Aesopus paused again and the crowd leaned forward expectantly.

����������� �There was once an old man and an ass walking down a road, very much like this one.� Aesopus began.� �They stopped to rest and the old man sat alongside the road, watching the ass graze in a field nearby.� Suddenly, the old man jumped at the sound of a band of men coming over a hill.� He knew who they were and he was afraid.

����������� ��Come along!� he said to the ass, �we have to get out of here now!� If they catch us, they�ll capture us and take us prisoner!�

����������� �The ass just kept on grazing.

����������� ��Didn�t you hear me?� said the old man.� �We�ve got to get out of here now!�

����������� ��Why?� said the ass.� �If they capture me, will they make me carry heavier burdens than you do?�

����������� ��No.� said the old man.

����������� ��So I would be no worse off than I am now.� You go on if you want to.� I�ll stay here and graze.��

����������� Some in the crowd laughed and talked among themselves.� Others just sat by the dying fire, their faces far away in thought.� I didn�t laugh.� I watched Aesopus walk away.� He turned from the crowd and stopped for a moment to lift a bundle of wood to his shoulder.� The weight of the bundle pushed him to the ground and made him small again.� I watched him become a slave again, fading into the darkness of the road that led back to his master�s house.

����������� �He was a great man, this Aesopus,� I said later to the other great men at the taverna.

����������� �What about this Aesopus?� asked the Great Cleatus.� �I thought we were talking about Paulus, the slave who became a great man.�

����������� �Baa,� said the Great Themistocles, �Slaves do not become great men.�

����������� �No, slaves do not become great men,� said the Great Darius, �but they can become great if they first become men.�

����������� �And what about a slave who never ceases to be a man?� I said.

����������� The Great Darius thought for a moment.

����������� �Then that man,� he said, �can never be a slave.�

����������� I smiled and saluted my old friend.� I finished my retsina as the sun descended.� I thought about all of the great men I had known in my life.� Then I took up my cart and went home.

Contact

Home