The Spell

By Frank Thomas Smith

Jenny Howard pushed open the unpainted, waist-high gate and walked into the front yard of her house. She paused a few feet from the door in order to take the key from her bag. As her eyes moved down to the bag she saw something on the worn doormat that caused her to take a step back and place her hand over her mouth to stifle a scream: a chicken's head with the blood not yet dry, alongside it two broken vials with their contents of red and yellow powder spilled out over the mat. She knew what it was of course. Anyone who lived in Brazil would recognize a Macumba spell. She breathed deeply several times, fished out her keys and stepped carefully over the abomination.

����������� Jenny was an American school teacher under contract to a foundation dedicated to enhancing educational levels in the third world. She was an idealistic young woman who was prepared for the sacrifices inherent in that kind of work. Her house, for example, was not much better than the shacks her pupils lived in a few blocks away in the favela, or shanty-town.

����������� Once inside, Jenny dropped her bag on the floor and sat down heavily in an overstuffed armchair. Her fingers were trembling so she clasped her hands together. Who could hate her enough to do such a thing? Her brooding lasted only a few seconds though. She stood up quickly, took a broom and hand-shovel from the kitchen and went outside to clean up. She didn't want Divino, her foster child from the favela, to see it when he came home from school. Then she put the broom aside and took a plastic trash-bag from a drawer. Outside she rolled up the mat with the chicken-head and powder inside it, put it in the bag and burned the whole mess in the backyard.

���������� Then she phoned Pedhro Branco, a sociology professor at the University of Sao Paulo and the man she was having an affair with. That he was married and had children didn�t disturb here as much as she thought it should. She knew he would never leave them and that constituted a guarantee that things would never go too far. She was somewhat surprised that he took what she told him seriously enough to come right over.

����������� "What bothers me is that someone would want to harm me,� she told him, �even if they chose that ridiculous way to do it. I thought I was, well, at least liked."

����������� "They love you, darling," Pedhro assured her. "But you must have offended someone, probably without even realizing it".

Jenny frowned, thought for a moment, then she gasped, "Of course, Zeca!"

����������� "What?"

����������� "I was just thinking of who it could be."

����������� "What are you going to do?"

����������� "Do? Why nothing of course."

����������� "But what if�"

����������� "If it happens again I'll complain to the police about someone putting trash on my doorstep."

����������� Pedhro shook his head. �I don�t think the police would want anything to do with Macumba.�

����������� Jenny was about to protest, but the door opened and seven-year-old Divino ran in. Jenny smiled and waved to him. He ran up to her and she bent down to kiss him.

����������� "I just wanted to get it off my chest to someone who wouldn't be horrified,� she said to Pedhro, switching to English from Portuguese. �Gotta go now."

����������� "Jenny."

����������� "Yes?"��

��������� "Macumba isn't something you can just ignore.� He also spoke in English so Divino wouldn't understand.

����������� "Oh, Pedhro, really." She laughed. "Not you too, professor. Look, we'll talk about it on Saturday, okay?"

����������� "Sure, but�"

����������� "You're full of surprises, darling. Maybe that's why I love you. Bye now."

����������� After supper, Jenny read a fairy tale to Divino and put him to bed. Then she prepared her classes for the next day and went to bed herself. Despite being tired from her usual exhausting day, she slept fitfully. Each time she woke up she thought of the Macumba spell. A heavy weight seemed to have descended on her heart, which annoyed rather than frightened her. She was not, she assured herself, afraid. She dozed off...

����������� "Jenny! Jenny!" It was Divino screaming.

����������� "Divino!" She sprang out of bed and ran into his room. She switched on the light and saw him standing on his bed pressed up against the wall staring in horror at the floor. A snake's flat, triangular head, red tongue flicking, was raised above its multi-colored scaled body under the open window. It was coiled, but stretched out it could have been three meters long.

����������� "Don't move, Divino, don't scream, I'm here," Jenny said, able to control her panic only because of Divino's greater need to control his. She stamped on the wooden floor and the snake uncoiled and dropped its head to the floor, turned it towards Jenny and raised it again. She stepped backwards into the hall, ran to the kitchen where she grabbed the axe she used for chopping wood, and rushed back to Divino's room.

����������� The snake ducked its head in a little bow and whipped its body around so it was pointing at Jenny. They stared, each waiting for the other to move. Finally the snake swished its tail and began to advance. When it was a yard away from her, Jenny swung the axe down with all her force. It struck just behind the snake�s head, chopping it off and burying itself in the floor. Then Jenny ran to Divino who was standing like a statue on his bed with urine running down his leg. She hugged and kissed him and they both fell onto the bed sobbing while the snake�s remains continued to writhe on the floor.

�It�s a surucucu,� Pedhro said when Jenny showed it to him at six o�clock the next morning.

�Is it poisonous?� Jenny asked.

�Very, and�well�cornered in a room like this, extremely dangerous. You�re lucky, Jenny, and brave.�

She looked at Pedhro just as he raised his eyes from the decapitated snake and their eyes met. This is no superstitious favelado, she thought. He�s a university professor, for God�s sake. And he�s worried. And so am I.

"Someone put that thing in Divino's room," she said. "Or do you think the Macumba spell hexed it out of thin air?"

����������� "No, someone must have put it there," he agreed, "but it's the spell that gave him the courage to do so."

����������� "What do you mean?"

����������� "Whoever it was feels that he's protected by the spirits once the spell is activated. It's a dangerous situation, Jenny � Black Macumba"

"The police�� she mumbled, but knew it would be useless.

����������� "Do you know who the local Macumba priestess is that the favela people go to for... ah ...advice?" Pedhro asked her.

����������� She thought a moment. "Yes, I think so. Dona �what�s her name? "

������ � "Josefina. I think you should go to her, Jenny."

����������� "But Pedhro, that's ridiculous."

����������� "I know, but go to her anyway. The only way to fight Black Macumba is with White Macumba. That�s what the people believe anyway.�

����������� "I will not give in to such superstitious nonsense," Jenny insisted.

����������� "That would be fine if only you were involved, but it looks like they're after Divino."��

��������� "Divino?" She closed her eyes and covered her mouth with her fist, trying to wish the thought away.

����������� "Of course. The snake was in his room, not yours. Do you feel that you have the right to risk his life?"

����������� "But why? Why Divino?"

����������� "Because it's the best way to get at you. You mentioned Zeca. Do you think he might be behind it?"

����������� "He�s the only one I can think of."

����������� "Who is he?"

����������� "A boy who worked in the clinic. I have to go now, Pedhro."

����������� "Do you want me to sleep here tonight?"

����������� "I don't know, I'll let you know." ��

Jenny left Divino at school and picked her way through the mud paths of the favela until she came to Dona Josefina's hut. She was sitting outside peeling potatoes with her legs spread apart so the peels would fall into her wide skirt. She was a heavy black woman who wore her graying hair in a huge afro. Jenny stood before her.

����������� "Good morning, Dona Josefina. I'm Jenny, from the school."

����������� "Good morning, Teacher Jennie. I am so glad you've come to see me. We are the two most important women in the favela, after all. It is good that we know each other." She looked up and Jenny was surprised to see a gentle smile on her lips.

����������� "Do you know who could have cast the spell?" Josefina asked after Jenny had told her the story.

����������� "I've thought about that and I think that, well, that it might be Zeca."

����������� "The boy who works in the clinic?"

����������� "Worked in the clinic. I had to let him go."

����������� "Why?"

����������� "We have a professional nurse now from America and Zeca was jealous, I suppose, and told the patients that she didn't know what she was doing."

����������� "Ah."

"But worse, he said that she was working for the devil."

"Ah...of course."

"What do you mean - of course?"

"I mean of course he would say that," Dona Josefina said with a sad smile. "And is she?"

����������� "Of course not. She's extremely competent and knowledgeable and Zeca isn't. I warned him, but he kept it up. He was endangering our work, so I told him he'd have to leave."

����������� "How did he take it?"

����������� "He didn't say anything. Just left. It was very difficult. He's been with me from the beginning."

����������� "And he's the only one?" Josefina asked, continuing to peel her potatoes.

���������� "Yes, I'm sure there's no one else."

����������� "I believe you. You are very well loved here."

����������� "Thank you."

����������� Jenny waited for her to say something else, but she remained silent, peeling, peeling.

����������� "What do you think I should do, Dona Josefina?" Jenny finally asked.

����������� "You should have come to me immediately, before crossing the threshold into your house. There is White Macumba and Black Macumba. You have become a victim of the Black, probably initiated at Zeca�s request by Pai Alfonso, from the Feliz favela. You must understand that firing Zeca in favor of a white female foreigner was a tremendous blow to his macho ego.� She sighed and her bosom heaved. "But you cannot change your decision now, it would mean giving in to the Black Macumba. You must fight it. Come this evening to our meeting."

����������� "Where?"

����������� "Here. And bring the boy."� ��

��������� Jenny was reluctant to go to a Macumba ceremony, white or black, but she was even more reluctant to continue living with the Macumba spell hanging over her � and Divino.

As Jenny and Divino approached Dona Josefina's shack that evening they heard wild drumming and smelled the penetrating odor of wine, incense and blood. Jenny hesitated at the door, but it was opened from inside and Sergio, one of her older pupils, solemnly took her hand and led them in.

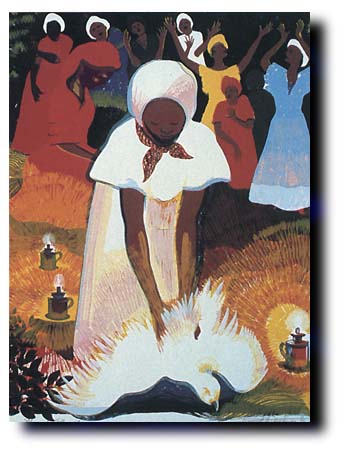

����������� The first thing she discerned in the semi-darkness was a black woman dressed entirely in red kneeling in a circle in the center of the overcrowded, candle-lit room. She held a convulsively twitching chicken fast while Dona Josefina, in a tent-like white gown adorned with pearls and stars, knelt in front of her with a large knife in her right hand and a bowl in the left. One eye was half-closed and the other goggled fearfully. Her hair was unbraided and flowed loosely over her shoulders and face like a dark cloud.

��������� Dona Josefina deftly slit the chicken's throat and caught its blood in the bowl. Then she poured in oil, wine and honey, dipped two fingers in it and slowly drew crosses on the other woman's forehead and throat.

����������� The woman in red sipped the horrible brew and immediately went into ecstatic convulsions similar to those of the slaughtered chicken, fell down, sprang into the air, danced wildly and finally threw herself onto the floor and rolled her eyes. Another woman went into the circle, knelt, sipped and danced wildly. Another chicken was sacrificed and so on, some fifteen times in Jenny's presence.

���������� At intervals the drums stopped beating, Dona Josefina tinkled a little bell and all was still. She moaned something about Domini and suddenly the singing, dancing and twitching continued.

����������� The room was crammed with sweating people, black and white, male and female, and many children who delightedly clapped their hands and sang along, as did Divino. Jenny wanted to draw the children around her as a protective wall.

����������� Suddenly Dona Josefina seemed to come out of her trance. She smiled and walked heavily to the door. They all poured out into the humid air. But it was only a break for costume change. Soon they were inside again for the second act.

����������� The atmosphere was completely different now: calm and solemn. The initiates, filhas de santos, were dressed in blossom-white gowns trimmed with lace. They formed a circle around a white tablecloth spread on the floor. A child put candles and flowers on it, then six plates. A woman brought Bahia food. Six children were permitted to eat of it.

���������� "It is an exorcism of the spirits which harm children," the woman next to Jenny whispered.

����������� When the children finished, a seventh plate was placed on the table and heaped with Bahia food. Josefina approached Jenny and Divino and held her hands out to them. Jenny expected the worst. The Bahia food was a concoction of manioca meal, a green liquid and a mountain of meat that would stick in her throat if she tried to eat it. But even worse was the cup being filled before her eyes: the chicken-blood cocktail.

����������� It turned out that Divino was to eat the food and she drink from the cup. The boy picked up the dripping chunks of meat and chewed them heartily as Jenny stared at the cup and then at the solemn, sweating faces surrounding her. If she didn't drink it would be an unpardonable offense. This was, after all, a religious ceremony. And why was she there if not to exorcise the spirits � real or otherwise � which threatened to harm Divino?

����������� She took a deep breath, closed her eyes, picked up the cup and drained it, praying that she would not vomit it up.

����������� Immediately the solemnity was transformed into violent drumming and dancing. Jenny thought she must faint, but somehow she didn't, and she even managed to keep the onerous concoction down.�

����������� �Finally it was over. Josefina kissed her and Divino and the others laughed and congratulated her. She walked out of the shack clutching Divino's hand and they headed up the hill towards home in the starless night.

����������� "Look, Jenny," Divino whispered, and pointed to the top of the hill.

����������� Jenny looked and saw a gaunt figure in gray shorts silhouetted against the sky. It was Zeca. Jenny pushed Divino behind her and drew a deep breath.

����������� "It's over, Zeca," she called out. "The spell has been exorcised by Dona Josefina."

����������� Zeca remained standing there and clenched his fists.

����������� "Go and don't come back or things will go badly for you," Jenny yelled and raised her own clenched fist.

����������� Zeca staggered backwards as though he had been struck in the chest. Then he turned and ran down the other side of the hill towards the avenida.

����������� The surucucu won't come back tonight, will it, Jenny?" Divino asked. Jenny scooped up the boy's light body and placed him on her shoulders, where he squealed with delight.

���������� "No, Divino, it will never come back again."

����������� Despite the weight on her shoulders, Jenny felt light and happy, for an awful weight had been lifted from her heart.��

Home

�����������