The Rise and Fall of the Airlines

by Frank Thomas Smith

Summer of 1965, January in the Southern Hemisphere. As the IATA Compliance Officer responsible for Argentina and Uruguay, I am conducting my post-investigation of a discounted ticket which I had purchased through an intermediary � euphemism for a person employed to act as a genuine passenger and obtain a discounted "test ticket� through a travel agency. The itinerary is Buenos Aires - Tel Aviv - Buenos Aires and the discount offered and accepted is twenty per cent.��

There is a large Jewish community in Argentina and no direct service to Israel, so the European airlines fight tooth and nail for the passengers, which explains the prohibited discount: �unfair� competition. Because the airlines use slush funds to grant discounts and take whatever precautions they can to avoid detection, the Compliance Officer (C.O.) is obliged to resort to clandestine tactics. The hiring of intermediaries as test purchasers (because the C.O. would be recognized) is only one example. I can't resist comparing it to my cold-war Military Intelligence service in West Berlin, from where we sent German agents into East Germany to gather intelligence about Soviet troops.

XYZ airline's manager expresses astonishment that his company's ticket was sold at a discount and claims to have received the full fare less seven percent commission from the travel agent. His astonishment is feigned and he knows that I know it. But he is also aware that whatever he says will become part of my report and he can never admit to granting the discount, for a fine of up to 25,000 dollars could be imposed on his airline � a tidy sum those days.

The owner of the travel agency we purchased the ticket from, sweating profusely, insists that he collected the full fare from the passenger. He has already been warned by the airline to play dumb. He has more to lose than the airline manager, for the travel agency is his livelihood. Like most of his colleagues, his fear of IATA is exaggerated. A penalty will apply to him, it is true, but it will be no more than a slap on the wrist. We know that the discount came from the airline and not from him. I try to trick him into confessing by using that angle.

"The discount was twenty per cent. You only receive seven per cent commission, so you couldn't have granted the discount. We know that, but the airline claims innocence and the blame may fall on you."

He considers this for a moment, frowning. Then he takes off his misted-over glasses and stares at me myopically. "We collected the full fare from the passenger, Mr. Smith. My accounts show it to be so."

Well, you can't blame me for trying.

The evidence, consisting of affidavits sworn by the intermediary and the Compliance Officer, wouldn't have held up in a court of law against the airline's and the travel agent's accounting records, but the IATA Breaches Commissioner � the de facto judge � knows that discounts are provided through slush funds and he invariably believes the Compliance Officer and not the airline. The two affidavits describe the purchase in minuscule detail.

The intermediary's:

"...After having received the sum of US$ 1.200 from the IATA Compliance Officer, for which I gave him my receipt (exhibit 1), I entered ABC travel agency at 2:06 p.m. I was attended by Sr. H. L�pez, who gave me his card (exhibit 2)...etc."

The Compliance Officer's:

"...I accompanied the intermediary to a point close to ABC travel agency, where I handed him the sum of� US$1.200, for which he gave me his receipt (exhibit 1 to his affidavit). He was to inquire for the price of a round trip ticket to Tel Aviv and broach the possibility of a discount. I saw him enter the travel agency at 2:06 p.m...etc."

Until now It's a routine case and I send my Violation Report to head office and concentrate on the other cases I have in the pipeline. I estimate a fine of about $15,000 for the airline and a 30 day suspension for the travel agent. The suspension means he shouldn't earn commission for sales made during that period. That won't cause him any problem though, he merely has to back-or pre-date his sales reports, with the connivance of the airlines.

In this age of deregulation, free markets, frequent traveler programs, deep discounts and open skies, it's hard to believe that it was once considered a mortal sin for an airline to grant a discount to a passenger � and to serve a free drink in economy class was of the venial variety. The thou-shalt-not commandments were formulated in the Manual of Traffic Conference Regulations of IATA (International Air Transport Association), the airline members of which�� possessed anti-trust immunity for the purpose of setting fares world-wide. These fares were approved by all the governments of the countries involved in the traffic and were rigidly enforced by IATA's own Compliance Division.

The Chief of IATA's Compliance Division, Rudolf Frick [not his real name], had his office on the fifty-second floor of 500 Fifth Avenue, just off 42nd Street in New York City. Originally German, but a naturalized, fervent American citizen, he ran his shop like a Wehrmacht general. Some underlings would not have been surprised if he had in fact once been one. He answered only to the Director General, Sir William Hildred, another original.

When Frick interviewed me for the position of Compliance Officer he made his authority crystal clear: "Mein men are like da fingers off my hands," he said as he held his hands in front of my eyes. Trouble was, he already had forty-five men in the field in practically every important airline city in the world. Even if he counted his toes, he couldn't reach that figure. He thought he controlled everything and everyone, but in fact his Compliance Officers were a motley pack of highly individualistic laws unto themselves. They had to be to have survived Frick's social darwinistic methods.

Training consisted of a month at the New York office studying the Manual and participation in a couple of minor investigations, followed by transfer to whatever country was deemed most in need of control. Often the new C.O. knew little or nothing about his new home and didn't speak the language. There was no office or infrastructure. He was on his own. Most, however, had airline experience. That was all right with Rudolf Frick though; he was a sink or swim man. If you sank you weren't fit to be one of his fingers.

I had been a Passenger Service Manager, sort of a glorified check-in agent, for American Airlines at New York's LaGuardia airport. When they computerized reservations and began replacing people by machines, I saw the writing on the wall and decided it was time to look elsewhere, so I answered a want-ad in the Times for an "airline investigator".

"I hire by intuition," Frick told me. "I am always right, and if I am not, too bad for you."

After thirty days stuck in a bare office with another trainee, I saw Mr. Frick for the second time. "I vant to transfer you to Buenos Aires, Mr. Smith. If you don't vant to go, you can vait a vhile. Soon I vill fire dat jackass ve haf in Calcutta and you can go dere!"

I went to the Fifth Avenue public library to confirm my suspicion that Buenos Aires is in Argentina and not Brazil. I also took out a book about Juan and Evita Per�n and a Spanish grammar. A week later I was on my way to Buenos Aires.

I filed my first Violation Report against the airline which carried me there. The beautiful Brazilian stewardess, with whom I fell in love for the duration of the flight, served free alcoholic drinks in economy class. The fine was $3,000. My conscience bothered me a little, as I was one of the passengers on whom she bestowed her lovely smile and the French wines. I knew she wouldn't get in trouble though. She was only carrying out the airline's policy.

Two months after submitting my Violation Report for the Buenos Aires--Tel Aviv test ticket, I receive the airline's defense via New York, together with a note from Rudolf Frick ordering me to reply immediately because the case is to be heard at the next Breaches Commission in one month's time. The airline claims that, unbeknownst to its manager in Argentina, a synagogue in Buenos Aires provided the discount to the passenger in the form of a scholarship because they want young Jewish men to visit Israel. A letter from the synagogue confirming this is attached, as well as another from the Argentine branch of the Israeli Tourism Office attesting to their knowledge of same.

Although the Breaches Commissioner is a retired airline executive who has seen almost every trick in the book and probably won't believe the story, he cannot ignore documentary evidence if it remains undisputed. I am in real danger of losing the case if I can't prove that the ingenious defense is false. The airline delayed submitting it until the last minute, hoping that I would have no time to do so.

I try to make an appointment with the head of the Israeli Tourist Office, but am told that the gentleman is (conveniently) out of town. I take a taxi to the synagogue, located in a working class, outlying district of Buenos Aires. One look at the address tells me that the synagogue would hardly be in a position to grant scholarships. But it also indicates that such a poor institution might have been willing to write the scholarship letter used in the airline's defense in order to receive a "donation". If so, I will try to shame them into admitting it. A long shot, but at least worth trying.

The rabbi, a bearded old man dressed in an ancient, shiny black suit, looks at the letter alleged to be from his synagogue and smiles ironically.

"Do we look as though we had money to grant scholarships?" he asks in Spanish with an East-European accent, peering at me over his glasses.

"It's a forgery then?" Which surprises even me.

"Of course," the rabbi confirms. "We haven't used this paper in ten years." He opens his desk drawer, takes out a sheet of blank stationery and hands it to me. "This is the paper we use now. I designed it myself."

The sheet of stationery shows the same name and address, but the lettering is different.

"Rabbi," I say, looking into the old man's honest eyes, "could you write a note on the new stationery affirming what you just told me?"

"I don't want trouble," the rabbi says.

"There will be no trouble for you." (I hope not anyway.) "This is strictly an IATA internal affair. Someone has misused your name for their own commercial purposes. It is not just."

The rabbi nods. "It is true what you say, young man. It is not just. You are American, are you not? I have friends in America. Things are different there, they tell me." He sits in his worn armchair sunken in thought for at least a minute. "Very well," he finally says, "What shall I write?"

When I get back to my office with what I am sure will clinch my case � the rabbi's letter disclaiming the false one � my secretary informs me that the intermediary phoned while I was out to say that he had been threatened by the Hagganah and that if he doesn't change his affidavit he will be killed. Therefore he will make a new affidavit saying that his discount was in reality a secret scholarship, so secret that even he didn't know about it until now.

"Call him," I tell her.

"He said he doesn't want to talk to you."

"Call him anyway."

The intermediary's mother answers and says he is out of town and won't be back for a long time.

I include the threat in my report, although I don't believe it for one moment. They convinced the intermediary to submit a new affidavit somehow, but the Zionist terrorist group Hagganah! Who do they think they're kidding?

The Breaches Commissioner finds the airline guilty and imposes the maximum fine of $25,000, commenting that he only regrets he isn't able to make the penalty more

severe. I found out much later that the airline offered the intermediary and his girlfriend a free trip to Israel in exchange for his cooperation. That's why he was out of town. Probably he made up the Hagganah story himself to get me off his back.

Policing the IATA fares agreements could become dramatic, as the above true story indicates. It all ended with deregulation though. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter appointed Alfred E. Kahn, a professor of economics at Cornell University, to be chair of the Civil Aviation Board. A concerted push for the legislation had developed, drawing on leading economists, leading 'think tanks' in Washington, a civil society coalition advocating the reform (patterned on a coalition earlier developed for the truck-and-rail-reform efforts), the head of the regulatory agency, Senate leadership, the Carter administration, and even some in the airline industry. This coalition swiftly gained legislative results in 1978 and deregulation became a fact of life. Although the European countries were unanimously opposed, the U.S. airlines were no longer able to participate in IATA traffic conferences and European, Asian and Latin American airlines which served the U.S were forced to comply or be sued for anti-trust activities. The free-for-all soon became a world-wide pattern.���

The Compliance Division was eventually downsized out of existence and the airlines are free to charge what they want. Whether deregulation was a good idea or not is still hotly debated in old-timer airline circles. The argument for regulation was that the airlines, as a public service, needed protection from their own competition, which allowed them to invest adequately in aircraft maintenance and safety. The argument for deregulation was that greater competition would result in lower fares for the public and more airlines providing better service.

A burst of new airlines did populate the firmament for a while, but shooting stars burn out quickly. Since then, the trend has been to fewer and bigger airlines. Whether the service is better in invariably jam-packed airplanes than it was under a regulated air transport industry can be judged by any frequent flier old enough to make the comparison.

Exposure to competition led to heavy losses and conflicts with labor unions for a number of carriers. Between 1978 and mid-2001, nine major U.S. carriers (including Eastern, Midway, Braniff, Pan Am, Continental, America West Airlines, and TWA) and more than 100 smaller airlines went bankrupt or were liquidated�including most of the dozens of new airlines founded in deregulation's aftermath.

It is true that the airlines sometimes abused their anti-trust immunity by imposing unrealistic fare structures. It was also very difficult for new carriers to gain market entry, and if they did, to survive. Nevertheless, there was real competition--in the form of service. If two carriers flew the same routes with the same aircraft and at the same fares, the passenger chose his airline by the standard of service on the ground and in the air. The result was that service standards were high. And there were many more airlines.

A smart IATA Compliance Officer knew the old game well. It was obvious to him that a weak carrier could not compete with a strong one (newer aircraft, better service, more frequencies) at the same fares. Therefore he was stricter with the strong carriers. He turned a blind eye to a ten per cent discount by a small Third World airline, glad that it wasn't thirty per cent. No such tolerance was granted to the quality carriers though. If they were tempted to go the discount route (and they were!) against their own interests, for it only forced the weaker airlines into deeper discounting, they had to be stopped immediately by means of the test ticket and the subsequent fine. This was an unwritten and unspoken law-and it worked.

Rudolf Frick had confidence in his people and defended us against myriad accusations, even if we outnumbered his fingers and once out of New York escaped his control in a pre-fax, pre-email era when telephones in exotic places often didn't work. He was interested in maintaining "clean", stable markets.

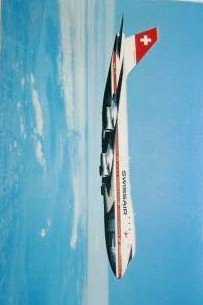

Presently the airlines' most competitive tool is price. And the big guy can use supermarket tactics to destroy the smaller or weaker guy and take the whole cake. Some great companies were destroyed by deregulation, and not only American ones. What a pleasure it was to fly with the now defunct Swissair, arguably the world's all time best airline! The survivors are the few giants . Most third world airlines, although they retain their original names, are in fact owned by foreign airlines, other financial entities or the state.

But that's the name of the business game today: dog eat dog and everyone loses � not only the passengers, the airlines as well, most of which are bankrupt or close to it. The question remains, therefore, to what extent air transportation is a public service which requires protection from the devastating effects of free market forces. In other words: re-regulation.