Words to Keep

by R. Ariel Gómez

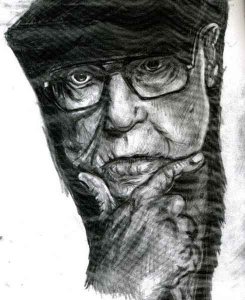

When my father returned from surgery his face was placid, illuminated. He smiled calmly, like when everything was in order. In his dreams, he had murmured a dialogue that I did not understand. He wasn’t aware of my presence, so I remained quiet, sitting by the side of his bed, trying to understand what had happened to us.

For more than thirty years my father had gall bladder stones, cleverly dodging surgeons until one day, as if from nowhere, he decided that yes, the stones would be removed, that those legendary battles with his doctors would stop once and for all.

The paradox is that it all started with a visit to the cardiologist because his usual arrhythmia was getting out of control.

“Look,” the cardiologist said, “I’ll fix the arrhythmia, but what we have to do, is to remove your gall bladder. It’s full of stones and at any moment it’ll burst or get infected and then we’ll have a hell of a mess. Just think that now it’s easy, a little tube… and the next day you’re in your house. We don’t even need to put you to sleep, which is important at your age. Think about it… you love to eat well and even if you wanted to, you wouldn’t be able to resist eating stuff you like. Or do you always want to be afraid of drinking a good wine or sharing a little barbeque with some friends? Think about it.”

For years my colleagues and friends tried to convince him with all kinds of arguments that the operation was necessary. But his answer was always the same: “These stones are mine and I’ll carry them to the grave,” and referring to me, in a playful tone he would say: “With the pardon of the Doc here, you’ve got to run away from doctors.” He would then smile, this mischievous smile that would disarm the studied logic of my friends who, not knowing how else to appeal to him, joined a feast he had prepared for them and eventually forgot about the matter. Now, I wonder whether my father, while repeating the famous phrase, might not have, accidentally or otherwise, reversed the relation: “These stones will carry me to the grave.” Or perhaps it was the astute cardiologist who did the trick and planted another idea in him: “Don’t let the stones be the ones to carry you.”

Like many other professionals, I had to leave the country, not because of the political prosecution and torture to which many of my friends, professors and colleagues were subjected, but rather because of a more insidious devastation: the intellectual ruin of the country after a madness that had consumed everything and with it the lives and future of so many young Argentines. Just a few days before leaving, my father told me, once again, what he’d been telling me since I was a child: “No one loves his or her children more than their parents. If things turn out bad, you can always return… One can always come back home…” Rarely was a thought so clear and enduring as that one was for me. Those simple but far-reaching words allowed me, over the years, to spread my wings, and face the unknown. Those words lived with me and armed me against adversity. I would have thought that the assurance conferred by such simple words would have disappeared with the disappearance of their creator. However, those words spoken casually took root and persisted, and I visited them more than once, in solitude, before the dread of the unknown, or the fear of failing, the most dreaded fear. With time I sensed that to be able to create, one has to have that kind of self-confidence, to know that one can, and should allow oneself to make a mistake, and by admitting and tolerating the possibility of failure be able to let loose, take flight. I know that creativity also emanates from darker places, but trying a new brushstroke, telling a different story, and opening a new path in music or science requires that intimate assurance, not only that it is worthwhile, but also that it is okay to take a risk. Of course you play to win, but if things go badly you can always return to the foundations, to familiar territory, to that internal home, mirror – sometimes mirage – of the original we constructed and carried on our backs for a lifetime. I don’t know if this applies to everyone, but in my case those words gave me the sustenance to imagine and dream. And later, when it was necessary, to emigrate.

Play and creation, inseparable siblings or… simply one and the same? It occurs to me that one cannot create without knowing how to play. And one cannot play without home, the place of the first games, where it is possible to imagine ghosts and frights under the gaze of those that we know love us unconditionally.

“You can always return,” my father had said. And with those words, he created a territory of protection, imaginary perhaps, but more powerful than reality itself. How did he guess? How did he know those words to be the most important thing to say to a son? How did he know to say those few but powerful words that created an entire place of refuge, and how will I know how to find the key words with my own children in an increasingly complicated world?

Since my departure, I had been coming and going to Argentina, visiting family and friends whenever the occasion presented itself. At first the trips were infrequent, every two or three years, then once or twice a year, alternating with a visit from my parents to the States, which usually culminated on the beaches of North Carolina where we had enjoyed together, as adults, many unforgettable moments.

It was actually during one of those trips that my father warned me: “One of these days I’m going to have the gall bladder removed, so when I visit you again we can drink one of those Californian wines with complete peace of mind.” I remember that I was surprised by that seemingly sudden decision. It was like changing an entire life, he and his inseparable stones. But my father did not make those kinds of decisions without thinking; obviously he had been chewing on the idea for some time. I didn’t think about the subject again until a few weeks later when his operation had already occurred.

I remember the message on the computer screen that made me travel to Argentina immediately:

“Dad…”

I took my time, on guard, sensing what was to come. The cursor blinked incessantly over the word I had voiced thousands of times: Dad, Dad, Dad… Dad? I knew it was bad news, and preparing myself for the worst, I opened the message: “call at once, but call us first.” I called immediately, and my sister and my brother-in-law explained nervously and with graphic details that my father had the gall bladder taken out and that he was fine but the gall bladder had cancer.

‘The gall bladder had cancer,’ a sentence that had a meaning beyond its simple grammatical construction. Meaning because of what it stated and also because of what, perhaps deliberately, had forgotten. A sentence that in other times I wouldn’t have paid the least attention, and that now seemed peculiar to me. Its peculiarity resided not in the grammatical construction but in what it implied, its profound meaning that harbored something more, a double meaning, like a hope and its antithesis. On the one hand I had no doubts that such construction tended to soften the blow and perhaps preserved a hope shared by the entire family. By saying that it was the gall bladder that had cancer, and knowing that now it was outside my father’s body, there was the possibility that he, my Dad, was clear of the illness. There lay the hope. Its opposite was the doubt: The gall bladder had fallen ill inside of him. The doubt that frightened all of us was whether the rest, that is to say, Dad, was healthy or not. Had something been left behind? Would he be cured? Would he die? All those question and many more passed thought my head while I listened now to only part of what they were saying. For the moment the answers were unknown, and the single word, cancer, paralyzed.

I got ready to travel as soon as I could. I consulted colleagues and did all I could do under the circumstances. And once in Buenos Aires, I accompanied my parents to the consultation with the oncologist, the unhappy possessor of a large body and a gigantic afro-look matched only by his rudimentary manners, seemingly more inclined to a plate of ravioli than to the psychological well being of his patients. He ignored my mother’s questions, although he responded to mine. He showed good medical judgment when he chose a treatment that took into account my father’s age and the state of his illness, but he didn’t show a trace of warmth. Good technocrat, I thought, but if he were my student, he would have earned an F in doctor-patient relationship.

Although my father barely felt the chemotherapy, he tolerated poorly the local radiation that burned his skin leaving bluish marks on his groin, a reminder that accompanied him to the end of his days. Until then, we thought that he would be okay, that since the gall bladder had been completely removed and just in time, the cancer would not spread. However, that was not the case. As in many others with this illness, the malignant cells had already emigrated from his gall bladder and invaded his lungs, his liver, and who knows what other secret places of his increasingly diminished body.

When we finally found out that the illness had spread, we agonized on several fronts. What should we say to him? Not saying anything would be to lie to someone we so loved and respected, and how else could we justify all the treatments and hospital admissions to which he would be submitted? But he had told us many times that if he ever were really sick, he didn’t want to know anything, he didn’t want to spoil, we supposed, the remaining days. More than once, I remember he told me: “the best thing would be to die in your sleep… you don’t realize anything, you don’t suffer, it’s over, and that’s that…” and he would add, “that would be, if I could choose, the way I’d like to die.”

We obeyed, pretending so that he could live the illusion of his healing, if he really ever believed it. We pretended so he would keep fighting, and entered a whirlpool that dragged in everyone and everything. One lie lead to another, and that one to another and so on until we no longer knew where we were and to what point we were capable of stretching our own dignity. The lie, that I now believe we shared with him and that at times we ourselves believed, suggested that once some setbacks with his lung and his recurrent arrhythmia had passed, he would return to his usual state, healthy and ready to enjoy those Argentinean-style barbecues for which he no longer had any appetite.

During this hospitalization, of the many he had, they had just taken out water from his lung: the cancerous cells had invaded the pleura, and he had a massive pleural effusion that was suffocating him. This time, the e-mail was more ominous:

“ Come quick, dad gravely ill.” I ran to the airport and I flew eight thousand miles with what I had on me but I arrived in time. They told me that in the days prior to the hospitalization, he could not walk even a few steps without becoming agitated. When he arrived to the clinic he could no longer talk. His skin was pale and bluish and his heart galloped out of control.

But now he slept peacefully. They had aspirated the liquid and he had a tube between his ribs that every so often drained an amber liquid into a bottle fastened to the bed. He breathed calmly, placidly. He would recover from this as he would recover from so many like this, but fewer questions remained now. We knew the final outcome.

And I found myself there, seated beside his hospital bed, waiting for him to open his eyes, to look at me, and to speak to me. Seated, waiting; what a difficult task for me, accustomed as I was to control my surrounding world. And I couldn’t help remembering my little patient, Jenny, who was so sick. “If you touch her, she dies,” the cardiologist said, “her heart has no strength.” It was true, her heart contracted slowly, feebly. Her blood barely flowed through her skinny body and her blood pressure was below the minimum advisable to perform hemodialysis. Her kidneys didn’t function, peritoneal dialysis had failed, and it was necessary to clean the impurities that accumulated in her body with uncanny speed. The risk that she would die during the procedure was great. The risk of her dying if we did nothing was, in my opinion, certain. But back then I was just a very fresh and unknown nephrologist, recently named assistant professor and still to gain the respect of my peers. “If we don’t touch her she also dies,” I responded, challenging the judgment of a prestigious professor who knew so much. And suppressing my own fears, putting my short career on the line, I pushed ahead and dialyzed her with all sorts of tricks they had taught me in the University of California, and despite all the bad omens, the girl survived. That night, while I dialyzed the child’s fragile and malnourished body, weighing as if she were three years old instead of ten, I thought many times of what my father would have done in a similar situation, and there was no doubt in my mind that at that moment his determination was guiding me. I didn’t talk with my father that night, but he was there.

Now those skills were of no use to me. At his bedside my role was limited: wait, sit, wait. They had told me, “Here, the best thing you can do is to be a son. Don’t try to be a doctor. You’ll help him more as a son.” And that’s what I did, but it was not easy, because not even being a son is easy. My parents had taught me so many things to defend myself that “to be,” already a given, is only the start. Action they taught me, to be “being.” And to be-being in constant growth, a kind of “being-will be.” How can one simply “be”? I rebelled against the static possibilities that implied a vegetative, automatic function. Even being a son was always being-will be, because my life and the lives of my parents were propelled and connected to ours by a need for evolution in which each event, each individual or common exploit was celebrated as part of that being and its projection toward the future.

Now he was resting. His breathing was gentle and rhythmic. He was smiling.

The monitor screen showed a steady and silent electrocardiogram, without those beeps they show in the movies, nothing dramatic. Everything quiet, in order. It was 5:30 AM, not yet time for the nurse to check his vitals: pressure, pulse, respiratory frequency, and temperature, a ritual that repeated itself every few hours, every day. “The problem,” my dad would say, “is that the patients don’t sleep because they are woken up regularly by the nurses, and irregularly by all kinds of other noises. Never knew a hospital can be so noisy. On top of being sick, they don’t let you sleep. Nobody sleeps here.”

How many times have I ordered frequent checks on a patient without realizing that they reassured me more than my patient? It suffices to stay in the hospital to realize that sometimes the routines of the medical staff and those of the patients exist in two distant worlds, separated by realities that have nothing to do with the reality of the outside world which moves with its own voracious rhythm, governed by capricious and incomprehensible laws. Watched from the inside, the outside is uncertain and disconcerting as if we had let loose a herd of lunatics that go everywhere without a clear direction; cars and people crossing all the streets and all the intersections at once, all of them running, as if running were the goal, as if arriving more quickly were the goal. Without knowing that in truth, it doesn’t matter so much. At least for he who is in a bed and sees the worlds pass, inflexible, following its own rules. And what he or she would like to do is to stop time or make it pass the way it did before, without realizing that it is passing, being part of the herd of lunatics that run without knowing that death has all the patience in the world. And thus we construct illusions of immortality to tolerate the end, inglorious attempts to fool ourselves into forgetting our inevitable, meaningless transience.

Through the window I glimpsed the promise of a new and sunny day. The rain had washed the air and only a few clouds interrupted the bluest sky. The day would be transparent and lively. The sparrows had already begun their merrymaking, a subtle chatter, almost unnoticeable at first, but when you take notice, it’s already a symphony at full force.

My father opened his eyes slowly. He looked at me as if he were returning from a foggy and distant place. I could tell he had trouble recognizing me, he struggled a bit solving the riddle and when he finally recognized me, he smiled broadly. He asked me if I have been there long and I told him that I had been with him the entire night, that as soon as I found out that he was hospitalized I traveled immediately to take care of him. As I began an explanation about my discussions with the doctors, he paid no attention and interrupted me with something that was apparently a thousand times more important.

“You know,” he said, “I had a great dream. I was with my dad, your grandpa, and he was young and good-looking as he was long before he died, he was happy, he was smiling and it gave me such tremendous joy to see him. We hugged for a long time, and I could feel his breath, and the aroma of his skin. He had that black mustache, and we were at your grandparents’ home, among the fig trees, remember, on the back of the house near the vegetable garden… But at the same time, I knew he wasn’t there and that I had been sick and that he had died many years ago. But I liked being with him and seeing him so happy. Then, he said ‘Negro, Chiche,’ as he used to call me when I was a kid, ‘Don’t worry, we will take care of you, you’ll be okay, everything’s going to be all right now…’ I didn’t want to wake up; I had never seen him so contented and serene. His serenity was palpable… And contagious… I don’t know, it gave me confidence, I guess. And what a joy to see him! I think that I got excited and woke up because I remember that I felt this urge, this impulse to jump and dance, and to call all my brothers and my mom and all you guys, the grandchildren and have a great party, but I knew what was happening was not entirely real, because when the old man had the black mustache I was younger, and you and your brothers had not yet arrived, but the urge to dance and jump did not go away and then I ran, I ran through the fields like when I was a kid, dodging the cows, scaring the teros*, the hens, and the rabbits which scattered in all directions. And when I awoke, I still felt the warmth of my dad's skin, the strength of his hug, his confidence, and his smile.

And so, my father related to me that encounter that was more powerful than all of medicine and all of history. I looked at him, dazed. He kept smiling, once more to the rescue, and I on my own journey, deciphering my dad's tranquility, which kept materializing, and which with each passing moment became more palpable, as if it were I who was awakening.

* Tero: Southern lopwing, typical bird from South America, commonly seen in low flat fields and coastal areas.

© R. Ariel Gómez

Contact“I grew up in a small town South of Buenos Aires. As a child, I was convinced that nothing ever happened there and wished to be whisked away where real adventures occurred. Unable to persuade my parents to flee with me to some exotic place, I escaped by reading and imagining all kinds of stories that at some point I started to write. Now that I have traveled for real, I keep discovering my little town, everywhere I go.

I am a scientist and a pediatrician and I am fortunate to direct a team of very talented researchers at the University of Virginia where we study how cells know their identity. Although I am thrilled when we discover the wondrous inner workings of a cell, science is not enough, and I have this pervasive longing to understand whatever more is there to understand. It is then, when a story appears, irresistible, inevitably taking over, transporting me once again, saving my day. My stories have appeared in Street Light, Hospital drive, and Puro Cuento. I live in Charlottesville with wife and my three wonderful children."

Home