One

Citizen’s Misadventure in Securityland

by

Ann

Jones

Where

did I go wrong? Was it playing percussion with an Occupy Wall

Street band in Times Square when I was in New York recently? Or was

it when I returned to my peaceful new home in Oslo and deleted an

email invitation to hear Newt Gingrich lecture Norwegians on the

American election? (Yes, even here.) I

don’t know how it happened. Or even, really, what happened. Or

what it means. So I’ve got no point -- only a lot of

anxiety. I usually write

about the problems of the world, but now I’ve got one of my

own. They

evidently think I’m a terrorist.

That

is, someone in the U.S. government who specializes in finding

terrorists seems to have found me and laid a heavy hand on my bank

account. I think this is wrong, of course, but try to tell that to a

faceless, acronymic government agency.

It

all started with a series of messages from my bank: Citibank. Yeah, I

know, I should have moved my money long ago, but in the distant past

before Citibank became Citigroup, it was my friendly little

neighborhood bank, and I guess I’m in a rut. Besides, I learned

when I made plans to move to Norway that if your money is in a small

bank, it has to be sent to a big bank like Citibank or Chase to wire

it to you when you need it, which meant I was trapped anyway.

So

the first thing I noticed was that one of those wires with money I

needed never arrived. When I politely inquired, Citibank told me that

the transaction hadn’t gone through. Why not? All my fault,

they insisted, for not having provided complete information. Long

story short: we went round and round for a couple of weeks, as I

coughed up ever more morsels of previously unsolicited personal

information. Only then did a bit of truth emerge.

The

bank wasn’t actually holding up the delivery of the money. The

funds had, in fact, left my account weeks before, along with a wire

transfer fee. The responsible party was OFAC.

Oh

what? I wondered. OFAC. It rhymes with Oh-Tack, but you’ve got

to watch how you pronounce it. Speak carelessly and the name sounds

like just what you might say upon learning that you’ve been

sucked into the ultimate top-secret bureaucratic sinkhole. It turns

out, the bank informs me, that OFAC is a division of the U.S.

Treasury Department that “reviews” transactions.

“Why

me?” I ask. As a long-time reporter I find it a strange

question, as strange as finding myself working on a story about me.

By

way of an answer, the bank refers me to an Internet link that calls

up a 521-page

report so densely typed it looks like wallpaper. Entitled

“Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons,” it

turns out to be a list of what seems to be every Muslim business and

social organization on the planet. That’s when I Google

OFAC, go to its site, and find out that the acronym stands for the

Office of Foreign Assets Control.

Its

mission description reads

chillingly. It “administers and enforces economic and trade

sanctions based on U.S. foreign policy and national security goals

against targeted foreign countries and regimes, terrorists,

international narcotics traffickers, those engaged in activities

related to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and

other threats to the national security, foreign policy or economy of

the United States.” And it turns out to be a subsidiary

of something much bigger that goes by the unnerving name of

“Terrorism and Financial Intelligence.”

Off

With Her Head

Whoa!

Perhaps it doesn’t help, at this moment, that I’ve just

been reading Top

Secret America: The Rise of the New American Security State,

the scary new book by Washington

Post

reporters Dana Priest and William M. Arkin about our multiple,

overfed, overzealous, highly-classified intelligence agencies,

staffed in significant part not by civil servants but by

profit-making private contractors. Suddenly, I feel myself in

the grip of the national post-9/11 paranoia that hatched all that new

“security.” (And you, too, could find yourself in

my shoes fast.)

I

check OFAC’s list more carefully. It’s in a kind of

alphabetical order, but with significant incomprehensible diversions

-- and if my name is there, I sure can’t find it. Since

I’ve spent most of the last decade working with international

aid organizations as well as reporting

from some of the more strife-ridden lands on the planet,

including Afghanistan,

the only thing I can imagine is that maybe all those odd visas in my

fat passport raised a red flag somewhere in Washington.

Next,

I search for the name of my Norwegian landlady. Did I say that

the wired funds that never arrived were meant to pay her my rent?

She’s in India, a volunteer health-care worker with Tibetan

refugees, currently helping refurbish an orphanage for 144 kids.

(What could be more suspicious than that?) I can’t find

her name either. No Anns or Heidis at all, in fact, among the

raft of Mohammads and Abduls.

Next,

I search for the name of my Norwegian landlady. Did I say that

the wired funds that never arrived were meant to pay her my rent?

She’s in India, a volunteer health-care worker with Tibetan

refugees, currently helping refurbish an orphanage for 144 kids.

(What could be more suspicious than that?) I can’t find

her name either. No Anns or Heidis at all, in fact, among the

raft of Mohammads and Abduls.

Heidi

is a Buddhist. I’m an atheist. Almost everybody on

the list seems to be Muslim, including really dangerous-sounding guys

like “Ahmed the Egyptian.” But I guess that to a

truly committed and well-paid terrorist hunter, we must all look

alike.

I’m

desperate to get the rent to Heidi so she can cover her own expenses

as a volunteer; an international organization pays for the children’s

needs, but Heidi does the work. So I call the American Embassy

in Oslo and speak to a nice young woman in the section devoted to

“American Citizen Services.” I tell her about me

and OFAC and Ahmed the Egyptian. She says, “I’ve

never heard of such a thing. But there are so many of these

intelligence offices now, I guess I’ll be hearing these stories

more often.” (Maybe she’s been reading Top

Secret America,

too.)

She

takes it up with her superiors and calls me back. The Embassy

can’t help me, citizen or not, she says, because they don’t

handle money matters and have nothing to do with the Treasury

Department.

“What?

The State Department doesn’t deal with the Treasury?”

“No,”

she says, “I guess not.”

Perhaps

since I last paid attention the Treasury stopped being considered

part of the government. Maybe it now belongs to Lockheed

Martin.

At

least the State Department has some compassion left in it. If

I’m really destitute, she assures me, the Embassy might

be

able to give me a loan to pay for a plane ticket that would get my

two cats and me back to the States. I guess it doesn’t

occur to her that under the circumstances I might feel more secure in

Norway.

Down

the Rabbit Hole

Still,

all I want to do is clear up this mess, so I put my head in the

lion’s mouth and send an email directly to OFAC. I tell

them that I’m in Norway for the year on a Fulbright grant as a

researcher -- that is, as part of an international exchange program

founded by a U.S. Senator and sponsored by the U.S. Government, or at

least one part of the State Department part of it. Among my

informal responsibilities, I add, is to be a goodwill ambassador for

the United States, but I’m finding it really hard to explain to

Norwegians that I can’t pay my rent because a bunch of

terrorist-trackers in the pay of my government have made off with the

money and left nothing behind but a list of Muslim names.

Remarkably

quickly OFAC itself writes back, giving me the creepy feeling that it

was lurking behind the door the whole time. It is sorry that I

am “frustrated.” It will help me, but only if I

supply a whole long list of information, mostly the same stuff I have

already provided three times to the bank, the same information the

bank later said wasn’t the issue after all. (Still later,

the bank would say that I had given not too little information, but

too much.) I send the requested tidbits back to “Dear

OFAC Functionary or Machine as the case may be.”

Two

days later comes another message from OFAC, this time signed by

“Michael Z.” Like Afghans, or spies, he evidently

has only one name, but my hopes that he might be an actual person

inexplicably rise anyway -- only to sink again when he claims OFAC

needs yet more information. All this so that Michael Z.,

presumed person, may help me “more effectively.”

(More than what, I wonder?) He is, he insists, trying to locate

my money with the help of my bank, which by the way is now blocking

me from seeing information about my own account online.

It

seems odd to me that this top-secret office of Financial Intelligence

somehow can’t manage to lay hands on the money it snatched from

me, but what do I know? I’m just a citizen.

Then

-- are you ready for this? -- comes what should be a happy ending.

A message from the bank tells me that the money has slipped through

after all, and sure enough there it is at last in a Norwegian bank,

only a month late. I won’t be evicted after all, and

Heidi will make sure those Tibetan kids get some fresh fruit and

brand new bright green curtains.

Still,

this is not a cheery story. So I have to send my apologies to the

long-dead Senator J. William Fulbright: I’m sorry indeed

that certain changes in the spirit and operations of the United

States have occurred since that day in 1948 when you launched your

farsighted program of grants to encourage open international

educational and cultural exchange. And I apologize that some of those

changes may have temporarily cramped my style as a goodwill

ambassador; I’ll try to get back on the job if I can just

figure out what hit me.

Was

this all simply a mistake? A technical glitch? An error

at the bank? I’d like to think so, but what about that

list of “Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons”?

Why was I directed to that?

And what about Michael Z., who presumably is some kind of

intelligence analyst at OFAC and who, when last heard from, was still

seeking information and trying to find the money?

Frankly,

this month-long struggle has left me mighty tired and uneasy.

Right now, Senator Fulbright, I’m lying low, down here at the

bottom of the rabbit hole, trying to make sense of things. (I took a

last look at the “Blocked Persons” list, and just this

week it’s grown by another page.) So I want to tell you

the truth, Senator, and I think that with your great interest in

peaceable international relations, you just may understand.

Strange as it may seem, since I’ve been hunkered down here in

the rabbit hole, I’ve worked up some sympathy for Ahmed the

Egyptian who, I have a sneaking feeling, could be down here, too.

It’s hard to tell when you’re kept in the dark, but maybe

he’s just another poor sap like me, snarled in the super-secret

security machine.

Ann

Jones is in Norway under the auspices of the Fulbright Scholar

Program, researching the Norwegian economic, social, and cultural

arrangements that cause it to be named consistently by the United

Nations as the best place to live on earth. A TomDispatch

regular, she is the author of Kabul

in Winter

(2006) and War

Is Not Over When It’s Over

(2010).

Copyright

2011 Ann Jones

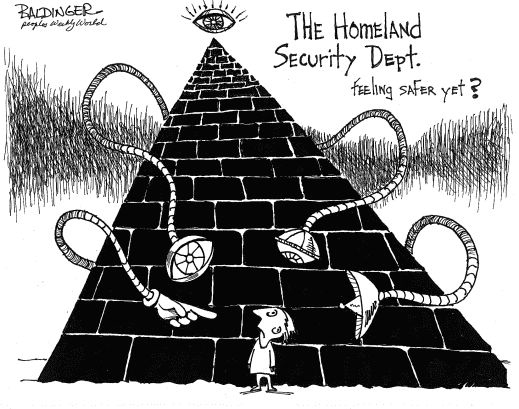

This

article originally appeared in TomDispatch.com without the image.

Home

Next, I search for the name of my Norwegian landlady. Did I say that the wired funds that never arrived were meant to pay her my rent? She’s in India, a volunteer health-care worker with Tibetan refugees, currently helping refurbish an orphanage for 144 kids. (What could be more suspicious than that?) I can’t find her name either. No Anns or Heidis at all, in fact, among the raft of Mohammads and Abduls.

Heidi is a Buddhist. I’m an atheist. Almost everybody on the list seems to be Muslim, including really dangerous-sounding guys like “Ahmed the Egyptian.” But I guess that to a truly committed and well-paid terrorist hunter, we must all look alike.I’m desperate to get the rent to Heidi so she can cover her own expenses as a volunteer; an international organization pays for the children’s needs, but Heidi does the work. So I call the American Embassy in Oslo and speak to a nice young woman in the section devoted to “American Citizen Services.” I tell her about me and OFAC and Ahmed the Egyptian. She says, “I’ve never heard of such a thing. But there are so many of these intelligence offices now, I guess I’ll be hearing these stories more often.” (Maybe she’s been reading Top Secret America, too.)She takes it up with her superiors and calls me back. The Embassy can’t help me, citizen or not, she says, because they don’t handle money matters and have nothing to do with the Treasury Department.“What? The State Department doesn’t deal with the Treasury?”“No,” she says, “I guess not.”Perhaps since I last paid attention the Treasury stopped being considered part of the government. Maybe it now belongs to Lockheed Martin.At least the State Department has some compassion left in it. If I’m really destitute, she assures me, the Embassy might be able to give me a loan to pay for a plane ticket that would get my two cats and me back to the States. I guess it doesn’t occur to her that under the circumstances I might feel more secure in Norway.Down the Rabbit HoleStill, all I want to do is clear up this mess, so I put my head in the lion’s mouth and send an email directly to OFAC. I tell them that I’m in Norway for the year on a Fulbright grant as a researcher -- that is, as part of an international exchange program founded by a U.S. Senator and sponsored by the U.S. Government, or at least one part of the State Department part of it. Among my informal responsibilities, I add, is to be a goodwill ambassador for the United States, but I’m finding it really hard to explain to Norwegians that I can’t pay my rent because a bunch of terrorist-trackers in the pay of my government have made off with the money and left nothing behind but a list of Muslim names.Remarkably quickly OFAC itself writes back, giving me the creepy feeling that it was lurking behind the door the whole time. It is sorry that I am “frustrated.” It will help me, but only if I supply a whole long list of information, mostly the same stuff I have already provided three times to the bank, the same information the bank later said wasn’t the issue after all. (Still later, the bank would say that I had given not too little information, but too much.) I send the requested tidbits back to “Dear OFAC Functionary or Machine as the case may be.”Two days later comes another message from OFAC, this time signed by “Michael Z.” Like Afghans, or spies, he evidently has only one name, but my hopes that he might be an actual person inexplicably rise anyway -- only to sink again when he claims OFAC needs yet more information. All this so that Michael Z., presumed person, may help me “more effectively.” (More than what, I wonder?) He is, he insists, trying to locate my money with the help of my bank, which by the way is now blocking me from seeing information about my own account online.It seems odd to me that this top-secret office of Financial Intelligence somehow can’t manage to lay hands on the money it snatched from me, but what do I know? I’m just a citizen.Then -- are you ready for this? -- comes what should be a happy ending. A message from the bank tells me that the money has slipped through after all, and sure enough there it is at last in a Norwegian bank, only a month late. I won’t be evicted after all, and Heidi will make sure those Tibetan kids get some fresh fruit and brand new bright green curtains.Still, this is not a cheery story. So I have to send my apologies to the long-dead Senator J. William Fulbright: I’m sorry indeed that certain changes in the spirit and operations of the United States have occurred since that day in 1948 when you launched your farsighted program of grants to encourage open international educational and cultural exchange. And I apologize that some of those changes may have temporarily cramped my style as a goodwill ambassador; I’ll try to get back on the job if I can just figure out what hit me.Was this all simply a mistake? A technical glitch? An error at the bank? I’d like to think so, but what about that list of “Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons”? Why was I directed to that? And what about Michael Z., who presumably is some kind of intelligence analyst at OFAC and who, when last heard from, was still seeking information and trying to find the money?Frankly, this month-long struggle has left me mighty tired and uneasy. Right now, Senator Fulbright, I’m lying low, down here at the bottom of the rabbit hole, trying to make sense of things. (I took a last look at the “Blocked Persons” list, and just this week it’s grown by another page.) So I want to tell you the truth, Senator, and I think that with your great interest in peaceable international relations, you just may understand. Strange as it may seem, since I’ve been hunkered down here in the rabbit hole, I’ve worked up some sympathy for Ahmed the Egyptian who, I have a sneaking feeling, could be down here, too. It’s hard to tell when you’re kept in the dark, but maybe he’s just another poor sap like me, snarled in the super-secret security machine.