Euro Blind

by Simon Critchley

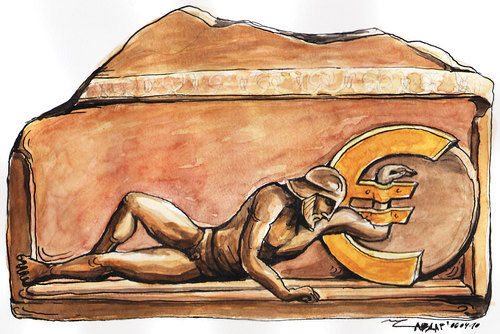

The past days, weeks and months have seen countless descriptions in the news media of the crisis in the euro zone and Greece’s role as its leading actor as a tragedy. But is it? Well, yes, but not in the sense in which it is usually discussed, and the difference is important and revealing.

In the usual media parlance, a tragedy is simply a misfortune that befalls a person (an accident, a fatal disease) or a polity (a natural disaster) and that is outside their control. While this is an arguably accurate definition of the word — something like it appears in many dictionaries — there is a deeper and more interesting understanding of the term to be found in many of the 31 extant Greek tragedies.

What these ancient tragedies enact over and over again is not misfortune outside a character’s control. Rather, they show the ways in which we humans collude, seemingly unknowingly, with the calamities that befall us.

Tragedy in Greek drama requires some degree of complicity. It is not simply a matter of malevolent fate, or a dark prophecy that flows from the inscrutable but often questionable will of the gods. Tragedy requires our collusion with that fate. In other words, it requires a measure of freedom.

It is in this way that we can understand the tragedy of Oedipus. With merciless irony (the first two syllables of the name Oedipus, “the swollen-footed,” also mean “I know,” oida), we watch someone move from a position of seeming knowledge — “I am Oedipus, some call me great; I solve riddles; now, citizens, what seems to be the problem?” (I paraphrase rather freely) — to a deeper truth that it would appear that Oedipus knew nothing about: he is a parricide and a perpetrator of incest.But there’s a back story that needs to be recalled. Oedipus turned up in Thebes and solved the Sphinx’s riddle only after refusing to return to what he believed was his native Corinth because he had just been given a prophecy about himself by the oracle: that he would kill his father and have sex with his mother.

Oedipus knew his curse. And, of course, it is on the way from the oracle that he meets an older man, who actually looks a lot like him, as his mother, Jocasta inadvertently admits later in the play, who refuses to give way at a crossroads and whom he kills in a fine example of ancient road rage.

One might have thought that, given the awful news from the oracle, and given his uncertainty about the identity of his father (Oedipus is called a bastard by a drunk at a banquet in Corinth, which is what first infects his mind with doubt), he might have exercised caution before deciding to kill an older man. Indeed, a reasonable inference to be drawn from the oracle would have been: “Don’t kill older men! You never know who they might be.”

One moral aspect of tragedy, then, is that we conspire with our fate. That is, fate requires our freedom in order to bring our destiny down upon us. The tricky paradox of tragedy is that we at one and the same time both know and don’t know our fate, and are destroyed in the process of its reckoning.

Napoleon is alleged to have said to Goethe that the role that fate played in the ancient world becomes the force of politics in the modern world. We then no longer require the presence of the gods and oracles in order to understand the ineluctable power of fate.

This is an interesting thought. But it does not imply that we are condemned to an unswerving fate by the political regimes under which we live. It is rather that we conspire with that fate and act — unknowingly, it seems — in such a way as to bring fate down upon our heads. Such is perhaps the life of politics. We get the governments that we deserve.

Keeping the euro crisis in mind, it is notable that tragic drama has a kind of boomerang structure: the action thrown out into the world returns with a potentially fatal velocity. Oedipus, the solver of riddles, becomes the riddle himself. Sophocles’ play shows him engaged in a relentless inquiry into the pollution that is destroying the political order, poisoning the wells and producing infant mortality. But he is that pollution.

The deeper truth is that Oedipus knows something of this from the get-go, but he refuses to see and hear what is said to him. Very early in the play, Tiresias, the blind seer, tells him to his face that he is the perpetrator of the pollution that he seeks to eradicate. But Oedipus simply doesn’t hear Tiresias. This is one way of interpreting the word “tyrant” in Sophocles’ original Greek title: “Oidipous Tyrannos.” The tyrant doesn’t hear what is said to him and doesn’t see what is in front of his eyes.

There is a wonderful Greek expression that I borrow here from the poet Anne Carson, “shame lies on the eyelids.” The point is that the tyrant experiences no shame; Hosni Mubarak had no shame; Muammar el-Qaddafi had no shame; Silvio Berlusconi had no shame; Rupert Murdoch has no shame.

Greek tragedy provides lessons in shame. When we learn that lesson and finally achieve some insight, as Oedipus does, then it must cost us our sight and we might pluck out our eyes — for shame.

The political world is stuffed overfull with sham shame, ham humility and staged tearful apologies. But true shame is something else.

The euro was the very project that was meant to unify Europe and turn a rough amalgam of states in a free market arrangement into a genuine social, cultural and economic unity. But it has ended up disunifying the region and creating perverse effects, such as the spectacular rise of the populist right in countries like the Netherlands, for just about every member state, even dear old Finland.

What makes this a tragedy is that we knew some of this all along — economic seers of various stripes had so prophesied — and still we conspired with it out of arrogance, dogma and complacency. European leaders — technocrats whom Paul Krugman dubbed this week “boring cruel romantics” — ignored warnings that the euro was a politically motivated project that would simply not work given the diversity of economies that the system was meant to cover. The seers, indeed, said it would fail; politicians across Europe ignored the warnings because it didn’t fit their version of the fantasy of Europe as a counterweight to United States’ hegemony. Bad deals were made, some lies were told, the peoples of the various member countries were bludgeoned into compliance often without being consulted, and now the proverbial chickens are coming home to roost.

But we heard nothing and saw nothing, for shame. The tragic truth that we see unspooling in the desperate attempts to shore up the European Union while accepting no responsibility for the unfolding disaster is something that we both willed and that threatens to now destroy the union in its present form.

The euro is a vast boomerang that is busy knocking over millions of people. European leaders, in their blindness, continue to act as if that were not the case.

Simon Critchley teaches philosophy at the New School for Social Research in New York. He is the author of many books and is the moderator of this series.

The Stone is a forum for contemporary philosophers on issues both timely and timeless.

Home