I

We will now continue our

study of karma. I have pointed out to you how the impulses in the

souls of human beings work on and are transplanted, as it were,

from one earthly life into another, so that the fruits of an

earlier epoch are carried over to a later one by people

themselves.

An idea such as this

must not be received merely as a theory; it should take hold of

our very hearts and souls. We should feel that we who are now

here have been many times in earthly existence, and that in every

life we assimilated the culture and civilisation then around us;

we took it into our souls and carried it over into the next

incarnation, after working upon it spiritually between death and

a new birth. Only when we look back in this way do we really feel

ourselves standing within the community of mankind.

In order to be able to

feel this, in order that in the coming lectures we may pass on to

questions which concern us more intimately and will bring home to

us the actual effects of karmic connections, I have found it

necessary to give concrete examples. And I have tried to show you

by these examples how the effects of what a man experienced and

achieved in olden times, remain, and continue to work into the

present, inasmuch as his achievements and experiences form part

of his karma.

I

spoke, for example, of Haroun al Raschid, that illustrious

follower of Mohammed in the 8th and 9th centuries, who was the

figurehead of a wonderful life of culture far surpassing anything

to be found in Europe in those days. [See Volume

1, lecture X;

also Cosmic

Christianity

lecture II (given by Rudolf Steiner in Torquay, 14th August,

1924).] Such culture as existed in Europe at that time — it

was during the reign of Charlemagne — was extremely

primitive; whereas over in the East at the Court of Haroun al

Raschid there came together everything that an Asiatic

civilisation fructified from Europe could produce — the

fruits of Greek culture and of ancient Oriental culture in

practically every domain of life and knowledge. Architecture,

astronomy (in the form in which it was pursued in those days),

philosophy, mysticism, the arts, geography, poetry — all

these branches of culture flourished at the Court of Haroun al

Raschid.

Haroun al Raschid

gathered around him the best of those who were of real account in

Asia at that time. For the most part they were men who had been

trained and educated in the Initiate Schools. Let me tell you of

one of these personalities at the Court of Haroun al Raschid. The

East, too, had reached its own Middle Ages, and this personality

had been able to assimilate, in a rather more intellectual way,

wonderful treasures of the spirit that had been carried over from

long past ages into those later times. In a much earlier period

he had himself been an Initiate.

Now as I have told you,

it may easily happen that a personality who was an Initiate in a

former age does not appear as one when he reincarnates, because

he is obliged to adapt himself to the body at his disposal and to

the educational facilities available at the time. Nevertheless he

bears within him all that he acquired and experienced during his

life as an Initiate.

In the case of

Garibaldi, we have seen how in that he became a kind of seer in

his life of will, giving himself up to the circumstances of the

immediate present, he lived out all that he had been as an Irish

Initiate. [See Vol. I, lectures XI and XII.] We can see that

while participating in the events of the day he bears within him

impulses of quite a different character from those which an

ordinary man could have gained from his education and

environment. The impulse of Garibaldi's Irish initiation was

still active; it was merely under the surface. And when some

special experience or stroke of destiny befell Garibaldi there

may very probably have welled up in him in the form of

Imaginations, all that he bore within him from his life as an

Irish Initiate.

So it has always been;

and so it is to this day. A person may have been an Initiate in

a certain epoch, and because in a later epoch he must make use of

a body unable to contain all the impulses that are alive in his

soul, he does not appear as an Initiate; nevertheless the impulse

of initiation is at work in his deeds or relationships in life.

So it was in the case of the personality who lived at the Court

of Haroun al Raschid. He had once been an Initiate of a very high

degree. He was not able to carry over in outwardly perceptible

form the whole content of his earlier initiation, but

nevertheless he was a shining light in the Oriental culture of

the 8th and 9th centuries. For he was, so to speak, the organiser

of all the sciences and arts studied and practised at the Court

of Haroun al Raschid.

We have already spoken

of the path taken by the individuality of Haroun al Raschid in

later times. When he passed through the gate of death there

remained with him the urge to carry further into the West the

Arabism that was already spreading in that direction. And, as you

know, Haroun al Raschid, whose field of vision embraced all the

several arts and sciences, reincarnated as Lord Bacon of Verulam,

the famous reformer of modern philosophy and science. All that

had been within Haroun al Raschid's field of vision came forth

again, in a Western guise, in Bacon.

The spiritual path taken

by Bacon led from Bagdad, his home in Asia, to England. And from

England, Bacon's work for the sciences spread over Europe more

widely and with greater force than is generally realised.

After they had passed

through the gate of death, these two personalities, Haroun al

Raschid and his great counsellor — the outstanding

personality who had been a high Initiate in earlier times —

separated, in order to carry out a common work. As I have told

you, Haroun al Raschid himself, who had occupied a position of

great power and splendour, chose the path which led to England,

where, as Lord Bacon of Verulam, he accomplished what he did for

science, for the sphere of knowledge in general. The other soul,

the soul of the man who had been his counsellor, chose the path

leading to Middle Europe, in order to meet there what was coming

over from Bacon. The dates do not, it is true, absolutely

coincide; but that is not important in a matter where actual time

means little. Impulses separated by hundreds of years may often

work simultaneously in a later civilisation.

The counsellor of Haroun

al Raschid chose the path through Eastern to Central Europe —

chose it during his life between death and a new birth. And he

was born again in Central Europe; he was born into the spiritual

life of Central Europe as Amos Comenius.

These are remarkable

events, of profound significance in history. Haroun al Raschid

goes through his later evolution in such a way as to lead over

from West to East a stream of culture that is abstract and bound

up with the outer senses; whereas Amos Comenius unfolds his

activity from the East, from Siebenbürgen in what is now

Czechoslovakia, coming to Germany and afterwards undergoing exile

in Holland, bringing with him his profoundly significant impulses

for the development of thought and knowledge. If you follow his

life you will see how he comes forward as the champion of the new

pedagogy and as the author and originator of the so-called

Pansophia. What he had formerly brought from his

initiation in very ancient times and developed at the Court of

Haroun al Raschid — all this he now brought to the

movements of the day. It was the time when the Order of the

Moravian Brothers had been founded, when Rosicrucianism had

already been at work for several centuries; it was the time, too,

when the Chymical Wedding had appeared, and also the

Reformation of Science, by Valentin Andreae. And into the

midst of all these movements which sprang from the selfsame

source, came Comenius, that significant figure of the l7th

century, with his message and his impulse.

You have there three

successive earthly lives of importance, and it is by studying the

more significant incarnations that one can learn how to study

those of less importance and finally begin to understand one's

own karma. — Three significant earthly lives follow one

another. First we see, far away in Asia, the very same

individuality who afterwards appears in Amos Comenius; we see him

receiving in the places of the ancient Mysteries all the wisdom

possessed by Asia in far distant ages; we see him carrying this

over into his next incarnation, living at the Court of Haroun al

Raschid, becoming there the great organiser and administrator of

all that flourished under the aegis and protection of Haroun al

Raschid. And then he appears again, this time going forth to meet

Bacon, who is the reincarnated Haroun al Raschid; he meets him in

European civilisation where the impulses which both of them had

caused to flow into this European civilisation are at work.

What I am now saying has

really great meaning. For if you will study the letters that were

written and that lay a road from Bacon to Comenius —

naturally they do so in a roundabout way, as is also the case

with letters today! — if you will study the letters that

were exchanged between Baconians, or between people in very close

connection with the Baconian culture and the followers of the

Comenius school, of the Comenius wisdom, you will be able to

discern in the writing and answering of these letters the very

same event that I have sketched diagrammatically on the

blackboard.

The letters that were

written from West to East and from East to West represent the

living confluence of the two souls who meet one another in this

way, having themselves laid the foundation for this meeting when

they worked together over in the East during the 8th and 9th

centuries. Now they unite again, to work once more in

co-operation; this time they work from opposite directions, yet

no less harmoniously.

This is the way in which

history should be studied in order to gain insight into the

working of human forces and the part they play in history.

Now let us take another

case. — It happened that peculiar circumstances drew my

attention to certain events that occurred in the region we should

now call the north-east of France. These events also took place

in the 8th–9th century — a little later, however,

than the time of which we were just now speaking. It was before

the formation of large States, in the days when events took place

more within smaller circles of people.

In the region, then,

which today we should call the north-east of France, lived a

personality who was full of ambitions. He had a large estate and

he governed it remarkably well, quite unusually systematically

for the time in which he lived. He knew what he wanted; there was

a strange mixture of adventurousness and conscious purpose in

him. And he made expeditions, some of which were more and some

less successful; he would gather soldiers and make predatory

expeditions, minor campaigns carried out with a small troop of

men with the object of plunder.

With such a band of men

he once set out from north-east France. Now it happened that

during his absence another personality, somewhat less of an

adventurer than himself, but full of energy, took possession of

all his land and property. — It sounds fictitious to-day,

but such things actually happened in those days. — And when

the owner returned home — he was all alone — he found

another man in possession of his estate. In the situation that

developed he was no match for the man who had seized his

property. The new possessor was more powerful; he had more men,

more soldiers. The rightful owner was no match for him.

In those times it did

not happen that if anyone were unable to go on living in his own

home and estate he immediately went away into some foreign

country. The rightful owner was an adventurer, certainly, but

emigration was not such an easy matter then; he had neither the

wherewithal nor the facilities. And so he became a kind of serf,

he with his followers — a kind of serf attached to his own

estate. His own property had been wrested from him and he,

together with a number of those who once used to accompany him on

adventures were forced to work as serfs.

In all these people who

were now serfs where formerly they had been masters, a certain

attitude of mind began to assert itself, an attitude of mind most

derogatory to the principle of overlordship. On many a night in

those well wooded parts, fires were burning, and round the fires

these men came together and hatched all manner of plots against

those who had taken possession of their property.

In point of fact, the

dispossessed owner, who from being the master of a large estate

had become a serf, more or less a slave, filled all the rest of

his life — as much of it as he was not compelled to give to

his work — with making plans for regaining his property. He

hated the man who had seized it from him.

And then, when these two

personalities passed through the gate of death, they experienced

in the spiritual world between death and rebirth all that souls

have been able to experience since that time, shared in it all,

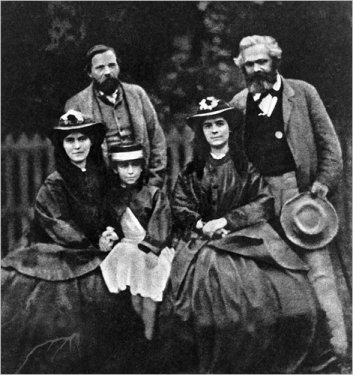

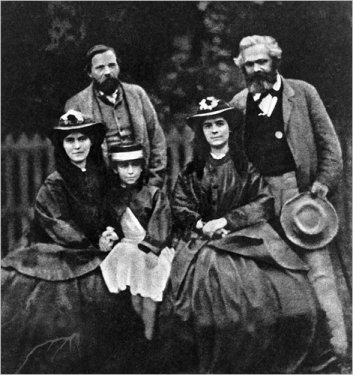

and came again to earth in the 19th century. The man who had lost

home and property and had become a kind of slave, appeared as

Karl Marx, the founder of modern socialism. And the man

who had seized his estate appeared as his friend Engels.

The actions which had brought them into conflict were

metamorphosed in the course of the long journey between death and

a new birth into an impulse and urge to balance out and set right

what they had done to one another.

Read what went on

between Marx and Engels, observe the peculiar configuration of

Marx's mind, and remember at the same time what I have told you

of the relationship between these two individuals in the 8th–9th

century, and you will find a new light falling upon every

sentence written by Marx and Engels. You will not be in danger of

saying, in abstract fashion: This thing in history is due to this

cause, and the other to the other cause. Rather will you see the

human beings who carry over the past into another age, in such a

way that although admittedly it appears in a somewhat different

form, there is nevertheless a certain similarity.

And what else could be

expected? In the 8th–9th century, when men sat together at

night around a fire in the forest, they spoke in quite a

different style from that customary in the 19th century, when

Hegel had lived, when things were settled by dialectic. Try all

the same to picture to yourselves the forest in north-eastern

France in the 9th century. There sit the conspirators, cursing,

railing in the language of the period. Translate it into the

mathematical-dialectical mode of speech of the 19th century, and

you have what comes to expression in Marx and Engels.

Such things lead us away

from sensationalism — which creeps all too easily into

ideas relating to the concrete facts of reincarnation —

towards a true understanding of history. And the best way to

steer clear of sensationalism is, instead of giving way to a

feverish desire to know the details of reincarnation, instead of

that, to try to understand in the light of the repeated earthly

lives of individual human beings, those things in history that

bring weal or woe, happiness or grief to mankind.

It was this point of

view that while I was still living in Austria — although in

Austria one is really within the Germanic world — I was

particularly interested in a certain personality who was a Polish

member of the Reichstag [parliament]. Those of you who have been

attending lectures for a long time will remember that I have

often spoken of Otto Hausner, the Austrian-Polish member of the

Reichstag who was so active in the seventies of the last century.

Truth to tell, ever since I heard and saw Otto Hausner in the

Austrian Reichstag about the end of the seventies and beginning

of the eighties, the picture of this remarkable man has been

before my mind's eye. He wore a monocle; he looked at you sharply

with the other eye, but all the time the eye behind the monocle

was watching for the weak points in his opponent. And while he

spoke, he was looking to see whether the dart had struck home.

Now Hausner had a

remarkable moustache — in my autobiography I did not want

to go into all these details — and he used to accompany

what he said with his moustache, so that the moustache made a

kind of Eurythmy of the speech he poured out against his

opponents!It is interesting when you picture it all. —

Extreme Left, Left, Middle Party, Czech Club (as it was called)

and then Extreme Right, Polish Club. Here stood Hausner, and over

on the extreme Left were his opponents. That was where all of

them were.

The curious thing was

that when, over the question of the occupation of Bosnia, Hausner

was on the side of Austria, he received tumultuous applause from

these people on the Left. When, later, he spoke about the

building of the Arlberg railway, the most vehement opposition

came from the same people on the extreme Left. And the situation

remained so, in regard to everything he said after that.

Very many warnings and

prophetic utterances made by Otto Hausner in the seventies and

eighties have, however, since proved true. One often has occasion

nowadays to look back in thought to what Otto Hausner used to

say.

Now there was one

feature that appeared in almost every speech Otto Hausner made,

and this, among other less significant details in his life, gave

me the impulse to investigate the course of his karma. Otto

Hausner could hardly make a speech without uttering a kind of

panegyric, as it were in parenthesis, on Switzerland. He was

forever holding up Switzerland to Austria as a model. Because in

Switzerland three nationalities get on well together, are indeed

quite exemplary in this respect, he wanted the thirteen

nationalities of Austria to take example from Switzerland and

live together in the same federal unity as do the three

nationalities of Switzerland. Again and again he would come back

to this theme. It was quite remarkable.

In Hausner's speeches

there was irony, there was humour, there was logic — not

always, but very often — and there was the

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panegyric

panegyric on Switzerland. It was perfectly clear that this

panegyric arose out of a pure feeling of sympathy; this feeling

gripped hold of him; he wanted to say these things. And moreover

he knew how to shape his speech so that no one, except a group of

German-Liberals on the Left, was seriously provoked or offended

by it.

It was most interesting

to see how, when some Left Liberal member had spoken, Otto

Hausner would get up to oppose him, and with his monocled eye

never turn his gaze aside for a moment but pour upon the Left

Wing a perfectly incredible torrent of abuse and scorn. There

were men of importance and standing among them, but he spared

none. And there was always breadth of view in what he said; he

was one of the most cultured members of the Austrian Reichstag.

The karma of such a

person may readily arouse interest. I took my start from this

passion of his for returning again and again to praise of

Switzerland, and further, from the fact that once in a speech

subsequently published as a brochure, German Culture and the

German Empire, he collected together in a spirit of

impishness and yet at the same time with nothing short of genius,

all there was to be said for German culture and the German

people and against the German Empire. There was really

something grandly prophetic about this speech that was made in

the early eighties, scuttling the German Empire as it were,

saying all manner of harsh things about it, calling it the

wrecker and destroyer of the true being and nature of the

Germans. That was the second thing — this singular ‘loving

hatred’, if I may put it so, and ‘hating love’

for all that is truly German, and for the German Empire.

And the third thing was

the extraordinary interest which made itself manifest when

Hausner spoke of the Arlberg Tunnel, of the plan to build the

Arlberg railway from Austria to Switzerland and thus unite

Central Europe with the West. Needless to say, here too he

introduced his song of praise for Switzerland, for the railway

was to run into Switzerland. But when he spoke of this railway —

and his speech was well-seasoned, though delivered with perfect

delicacy — one really had the feeling: the man is basing it

all on tendencies and proclivities he must have acquired in some

remarkable way in a former earthly life.

Everyone was talking in

those days of the enormous advantages that would accrue to

European civilisation from the alliance of Germany with Austria.

At that very time Hausner was developing in the Austrian

Parliament his idea of the Arlberg railway; he was saying, and

naturally all the others were going for him hammer and tongs

about it, that the Arlberg railway must be built, because a State

as he pictured Austria, uniting thirteen nations after the

pattern of Switzerland, must have a choice of allies; when it

suits her, Austria has Germany, and when it suits her she must

also have a strategic route from Central Europe to the West, so

that she may be able to have France for an ally when she wishes.

Naturally, when such an opinion was expressed in the Austria of

those times, it received short answer! It was reported that

Hausner was ironed out flat! In truth, however, it was a

marvellous speech, highly spiced and full of poignancy. And this

speech, I would have you note, pointed in the direction of the

West.

Holding these three

things together in mind, I discovered that the individuality of

Otto Hausner had wandered across Europe from West to East at the

time when Gallus and Columbanus [Not St. Columba, but a slightly

younger Irish monk — St. Columbanus (sometimes called

Columba the Younger).] were journeying in the same direction. He

set out with men who had been inspired by the Irish initiation

for the purpose of bringing Christianity to those regions. In

company with them, his aim was to carry Christianity to the East.

On the way, somewhere in the neighbourhood of the Alsace of

to-day, he found himself extraordinarily attracted by the relics

of ancient Germanic paganism, by the old memories of the gods,

the old forms of worship, the figures and statues of the gods

that he found in Alsace, and also in Germany and Switzerland. He

received all this into his heart and mind in a deeply significant

way.

Afterwards there

developed in him, on the one hand, a liking for the Germanic

nature and, on the other hand a counterforce which came from the

feeling that he had gone too far in that past life. He underwent

a drastic inner change, an inner metamorphosis, and this showed

itself in the wide and comprehensive outlook he possessed in this

later incarnation. He could speak of the German people and

culture and of the German Empire like one who has once had close

and intimate contact with these things, and yet who feels all the

time that he ought not to have been influenced by them. He should

have been spreading Christianity. He had come into these parts

while his duty lay elsewhere. — One could hear it in the

very tone of his speeches. — And he wanted to go back and

make good again! Hence his passion for Switzerland; hence his

passion for the building of the Arlberg railway. Even in outward

appearance, he did not really look Polish. Hausner himself used

often to say that he was not a Pole at all by physical descent

but only by civilisation and education, and that ‘Raetian-German’

blood flowed in his veins. He had brought over from an earlier

incarnation the tendency to look towards the region where once he

had been, whither he had accompanied St. Columbanus and St.

Gallus with the resolve to spread Christianity, but where,

instead, the old Germanic religion and culture had captured him

and held him fast. And so it came about that he did his best, as

it were, to be born again in a family as little Polish as

possible, far away from the land in which he had lived in his

earlier life, far removed from it and yet so that he could look

longingly towards it.

These are examples which

I wanted to unfold before you today in order to show you how

strange and remarkable is the path of karmic evolution. —

In the next lecture we shall consider the question of how good

and evil develop through successive incarnations of human beings,

and through the course of history. By studying in this way the

more important and significant examples that meet us in history,

we shall be able to throw light on relationships belonging more

to everyday life.

Continued in the next

issued of Southern Cross Review.

Thanks to the Rudolf

Steiner Archve.

home