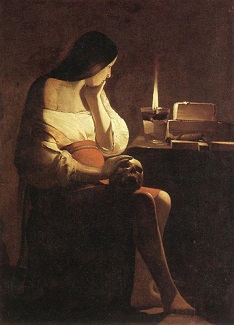

Magdalena - Georges de La Tour

Memento Mori

The Death of American Exceptionalism - and of Me

by Lewis H. Lapham

It’s not that I’m afraid to die, I just don’t want to be there when it happens.-- Woody AllenI admire the stoic fortitude, but at the age of 78 I know I won’t be skipping out on the appointment, and I notice that it gets harder to remember just why it is that I’m not afraid to die. My body routinely produces fresh and insistent signs of its mortality, and within the surrounding biosphere of the news and entertainment media it is the fear of death -- 24/7 in every shade of hospital white and doomsday black -- that sells the pharmaceutical, political, financial, film, and food products promising to make good the wish to live forever. The latest issue of my magazine, Lapham’s Quarterly, therefore comes with an admission of self-interest as well as an apology for the un-American activity, death, that is its topic. The taking time to resurrect the body of its thought in LQ offered a chance to remember that the leading cause of death is birth.I count it a lucky break to have been born in a day and age when answers to the question “Why do I have to die?” were still looked for in the experimental laboratories of art and literature as well as in the teachings of religion. The problem hadn’t yet been referred to the drug and weapons industries, to the cosmetic surgeons and the neuroscientists, and as a grammar-school boy in San Francisco during the Second World War, I was fortunate to be placed in the custody of Mr. Charles Mulholland. A history teacher trained in the philosophies of classical antiquity, Mr. Mulholland was fond of posting on his blackboard long lists of noteworthy last words, among them those of Socrates, Marcus Aurelius, Thomas More, and Stonewall Jackson.The messages furnished need-to-know background on the news bulletins from Guadalcanal and Omaha Beach, and they made a greater impression on me than probably was expected or intended. By the age of 10, raised in a family unincorporated into the body of Christ, it never once had occurred to me to entertain the prospect of an afterlife. Eternal life may have been granted to the Christian martyrs delivered to the lions in the Roman Colosseum, possibly also to the Muslim faithful butchered in Jerusalem by Richard the Lionheart, but without the favor of Allah or early admission to a Calvinist state of grace, how was one to formulate a closing remark worthy of Mr. Mulholland’s blackboard?The question came up in the winter of 1953 during my freshman year at Yale College, when I contracted a rare and particularly virulent form of meningitis. The doctors in the emergency room at Grace-New Haven Hospital rated the odds of my survival at no better than a hundred to one. To the surprise of all present, I responded to the infusion of several new drugs never before tested in combination. For two days, drifting in and out of consciousness in a ward reserved for patients without hope of recovery, I had ample chance to think a great thought or turn a noble phrase, possibly to dream of the wizard Merlin in an oak tree or behold a vision of the Virgin Mary. Nothing came to mind.Nor do I remember being horrified. Astonished, but not horrified. Here was death making routine rounds, not to be seen wearing a Halloween costume but clearly in attendance. The man in the next bed died on the first night, the woman to his left on the second. Apparently an old story, but before being admitted to the hospital as a corpse in all but name, it was not one that I had guessed was also my own. I hadn’t been planning any foreign travel, and yet here I was, waiting for my passport to be stamped at the once-in-a-lifetime tourist destination that doesn’t sell postcards and from whose museum galleries no traveler returns.Minus three toes destroyed by the disease, I left the hospital four months later knowing that my reprieve was temporary, subject to cancellation on short notice. Blessed by what I took to be the smile and gift of fortune, I resolved to spend as much time as possible in the present tense, to rejoice in the wonders of the world, chase the rainbows of the spirit, indulge the pleasures of the flesh, defy the foul fiend, go and catch a falling star.

I had been outfitted with a modus vivendi but no string of words with which to account for it, and so for the next three years at college I searched out writers who had drawn from their looking into the face of death a line of poetry or the bulwark of a philosophy. I don’t now remember how accurately or in what sequence I first read, but I know that with several of them -- Michel de Montaigne and Seneca the Younger, Plutarch, W.H. Auden, and John Donne -- I’ve stayed in touch.Their collective counsel continues to confirm me in the opinion reached in Athens by Epicurus in the fourth century B.C., transmuted into verse by the Roman poet Lucretius at about the same time that Caesar invaded Gaul, and rendered as equations in the twentieth century by Ernest Rutherford and Niels Bohr. If it’s true that the universe consists of atoms and void and nothing else, then everything that exists -- the sun and the moon, mother and the flag, Beethoven’s string quartets and da Vinci’s decomposing flesh -- is made of the elementary particles of nature in fervent and constant motion, colliding and combining with one another in an inexhaustibly abundant variety of form and substance. No afterlife, no divine retribution or reward, nothing other than a vast turmoil of creation and destruction. Plants and animals become the stuff of human beings, the stuff of human beings food for fish. Men die not because they are sick but because they are alive.Old-Fashioned Death“Death… the most awful of evils,” says Epicurus, “is nothing to us, seeing that when we are, death is not yet, and when death comes, we are not.” My experience in the New Haven hospital demonstrated the worth of the hypothesis; the books I read in college formed the thought as precept; my paternal grandfather, Roger D. Lapham, taught the lesson by example.In the summer of 1918, then a captain of infantry with the American Expeditionary Force in World War I, he had been reported missing and presumed dead after his battalion had been overwhelmed by German poison gas during the Oise-Aisne offensive. Nearly everybody else in the battalion had been promptly killed, and it was six weeks before the Army found him in the hayloft of a French barn. A farmer had retrieved him, unconscious but otherwise more or less intact, from the pigsty into which he had fallen, by happy accident, on the day of what had been planned as a swift and sure advance.The farmer’s wife nursed him back to life with soup and soap and Calvados, and by the time he was strong enough to walk, he had lost half his body weight and undergone a change in outlook. He had been born in 1883, descended from a family of New England Quakers, and before going to Europe in the spring of 1918 was said to have been almost solemnly conservative in both his thought and his behavior, shy in conversation, cautious in his dealings with money. He returned from France reconfigured in a character akin to Shakespeare’s Sir John Falstaff, extravagant in his consumption of wine and roses, passionate in his love of high-stakes gambling on the golf course and at the card table, persuaded that the object of life was nothing other than its fierce and close embrace.Which is how I found him in the autumn of 1957, when I returned to San Francisco to look for work on a newspaper. He was then a man in his middle seventies (i.e., of an age that now surprises me to discover as my own), but he was the same vivid presence (round red face like Santa Claus, boisterous sense of humor, unable to contain his emotions) that I had known as a boy growing up in the 1940s in the city of which he was then the mayor.A guest in his house on Jackson Street for three months before finding a room of my own, most mornings I sat with him while he presided over his breakfast (one scrambled egg, two scraps of Melba toast, pot of coffee, glass of Scotch) listening to him talk about what he had seen of a world in which he knew that all present (committee chairman, lettuce leaf, and Norfolk terrier) were granted a very short stay. Although beset by a good many biological systems failures, he regarded them as nuisances not worth mention in dispatches. He thought it inadvisable to quit drinking brandy, much less the whiskey, the rum punch, and the gin. At the bridge table he continued to think it unsporting to look at his cards before bidding the hand.My grandfather’s refusal to consult doctors no doubt shortened his length of days on Earth, but he didn’t think the Fates were doing him an injustice. He died in 1966 at the age of 82 on terms that he would have considered sporting. The grand staircase in his house on Jackson Street was curved in a semicircle rising 30 feet from the entrance hall to a second-floor landing framed by a decorative wooden railing. Having climbed the long flight of stairs after a morning in the office and the afternoon on a golf course, Roger Dearborn Lapham paused to catch his breath. It wasn’t forthcoming. He plunged head first through the railing and was dead -- so said the autopsy -- before his body collided and combined with the potted palm at the base of the stairwell. He had suffered a massive heart attack, and his death had come to him in a way he would have hoped it would, as a surprise.An Immortal Human Head in the CloudsAbout the presence of death and dying I don’t remember the society in the 1950s being so skittish as it has since become. People still died at home, among relatives and friends, often in the care of a family physician. Death was still to be seen sitting in the parlor, hanging in a butcher shop, sometimes lying in the street. By the generations antecedent to my own, survivors of the Great Depression or one of the nation’s foreign wars, it seemed to be more or less well understood, as it had been by Montaigne that one’s own death “was a part of the order of the universe… a part of the life of the world.”For the last 60 or 70 years, the consensus of decent American opinion (cultural, political, and existential) has begged to differ, making no such outlandish concession. To do so would be weak-minded, offensive, and wrong, contrary to the doctrine of American exceptionalism that entered the nation’s bloodstream subsequent to its emergence from the Second World War crowned in victory, draped in virtue.Military and economic command on the world stage fostered the belief that America was therefore exempt from the laws of nature, held harmless against the evils, death chief among them, inflicted on the lesser peoples of the Earth. The wonders of medical science raked from the ashes of the war gave notice of the likelihood that soon, maybe next month but probably no later than next year, death would be reclassified as a preventable disease.That article of faith sustained the bright hopes and fond expectations of both the 1960s countercultural revolution (incited by a generation that didn’t wish to grow up) and the Republican Risorgimento of the 1980s (sponsored by a generation that didn’t choose to grow old). Joint signatories to the manifesto of Peter Pan, both generations shifted the question from “Why do I have to die?” to the more upbeat “Why can’t I live forever?”The substituting of the promise of technology for the consolations of philosophy had been foreseen by John Stuart Mill as the inevitable consequence of the nineteenth century’s marching ever upward on the roads of social and political reform. Suffering in 1854 from a severe pulmonary disease, Mill noted in his diary on April 15, “The remedies for all our diseases will be discovered long after we are dead, and the world will be made a fit place to live in after the death of most of those by whose exertions have been made so.”His premonition is now the just-over-the-horizon prospect of life everlasting bankrolled by Dmitry Itskov, a Russian multimillionaire, vouched for by the Dalai Lama and a synod of Silicon Valley visionaries, among them Hiroshi Ishiguro and Ray Kurzweil. As presented to the Global Future 2045 conference at Lincoln Center in New York City in June 2013, Itskov’s Avatar Project proposes to reproduce the functions of human life and mind on “nonbiological substrates,” do away with the “limited mortal protein-based carrier” and replace it with cybernetic bodies and holograms, a “neohumanity” that will “change the bodily nature of a human being, and make them immortal, free, playful, independent of limitations of space and time.” In plain English, lifelike human heads to which digital copies of the contents of a human brain can be downloaded from the cloud.The question “Why must I die?” and its implied follow-up, “How then do I live my life?,” both admit of an answer by and for and of oneself. Learning how to die, as Montaigne goes on to rightly say, is unlearning how to be a slave. The question “Why can’t I live forever?” assigns the custody of one’s death to powers that make it their business to promote and instill the fear of it -- to church or state, to an alchemist or an engineer.For 40 years during the Cold War, the American government, both Democrat and Republican, deployed the shadow of death (i.e., the constant threat of nuclear annihilation) to limit the freedoms and quiet the voices of the American people. The surveillance apparatus now waging the perpetual war on terror is geared to control a herd of trembling obedience.The settled opinion that Americans don’t deserve to die -- not their kind of thing -- protects the profits of the insurance, healthcare, pharmaceutical, and media industries, puts the money on the table for the cruise missile, the personal trainer, and the American Express card that nobody can afford to leave home without.“I Am Ready to Depart”My grandfather didn’t shop the markets in immortality. Neither did my father. Although markedly different in character and temperament (his turn of mind was contemplative, his sense of humor skeptical), he shared my grandfather’s scorn for the wish to live forever. What for? To do what? To suffer the trauma of modern medicine and endure the mortifications of the flesh in order to eat another season of oysters, go south for one more winter in the sun?He had earned his living as the president of a steamship company and the vice chairman of a bank; he had devoted his leisure to the study of history and the reading of literature. He didn’t believe in miracles or magicians, as wary of divine revelation as he was of economic forecasts and predictions.In his late seventies he wrote a will stating that his life was not to be artificially prolonged. The hospital machinery he regarded as sophisticated instruments of torture, up to the standard of the Spanish Inquisition. He would have agreed with film director Luis Buñuel that “respect for human life becomes absurd when it leads to unlimited suffering, not only for the one who’s dying but for those he leaves behind.” He also understood, as had Thomas Jefferson in a letter to Dr. Benjamin Rush in 1811, that “there is a fullness of time when men should go, and not occupy too long the ground to which others have a right to advance.”During the last three years of his life, my father began to show signs of bodily malfunction (arthritis in his hands, forgetting where he put a letter or his hat), but on the weekends when I drove up from New York to his home in Connecticut, he never once complained of his afflictions. He spent his time planting the property with the seedlings of white oak and red maple trees and rereading the authors who had been his lifelong boon companions, many of them the ones whom I had met in college.Our conversation was lighthearted and anecdotal, my own reference to Aeschylus having been killed by a turtle dropped on his head by a clumsy eagle topped by my father being reminded of Seneca’s observation that “death is a punishment to some, to some a gift, and to many a favor.” It wasn’t hard to know in which categories he placed himself. Among the poems he admired was the one composed by Walter Savage Landor on the occasion of his 75th birthday:I strove with none for none was worth my strife.

Nature I loved, and next to nature, art;

I warmed both hands before the fire of life.

It sinks, and I am ready to depart.And so was Lewis Abbot Lapham on the night he died in December 1995 at the age of 86. A snowstorm had delayed my usual time of arrival in Connecticut, and when I sat down in the chair next to his bed, he greeted me with what proved to be his final remark, “It’s a hard life, Doc, and not many of us make it out alive.” For the next two hours I sat there holding his hand, neither of us saying anything, listening to wind play upon the windowpanes. He had packed his bags, checked out of the hotel, and was waiting in the lobby for the car to take him to the airport.I neither hope nor expect to be among the chosen few who make good their escape from the wheel of fortune and the teeth of time. Or that having been granted a 60-year extension on the deadline for a last noteworthy thought or phrase I’ll have reached the serenity of soul to which Thomas More gave a last and living proof while mounting the scaffold to his execution and saying to the headsman with the axe, “See me safe up, and for my coming down let me shift for myself.”If my luck holds true to its so far winning form, death will drop by uninvited and unannounced, and I’ll be taken, as was my grandfather, by surprise, maybe in the throes of trying to write a stronger sentence or play a perfect golf shot. If not, I’ll hope to show at least a semblance of the composure to which many of the authors in the latest issue of Lapham’s Quarterly bear immortal witness. Certain only that the cause of my death is one that I can neither foresee nor forestall, I’m content, at least for the time being, to let the sleeping dog lie.

[This essay will appear in "Death," the Fall 2013 issue of Lapham's Quarterly. This slightly adapted version is posted at TomDispatch.com with the kind permission of that magazine.]Lewis H. Lapham is editor of Lapham’s Quarterly and a TomDispatch regular. Formerly editor of Harper’s Magazine, he is the author of numerous books, including Money and Class in America, Theater of War, Gag Rule, and, most recently, Pretensions to Empire. The New York Times has likened him to H.L. Mencken; Vanity Fair has suggested a strong resemblance to Mark Twain; and Tom Wolfe has compared him to Montaigne. This essay, slightly adapted for TomDispatch, introduces "Death," the Fall 2013 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, soon to be released at that website.Copyright 2013 Lewis Lapham

Home