Mañana, María

by JP Miller

I’m sitting—no, reclining—in an oversized hospital chair at Ft. Kessler, Biloxi, Mississippi and dangling my legs over the thing, trying to get the energy to attempt to walk again. My right leg doesn’t want to work. It doesn’t help that I have various tubes in my arms. If I get up to attempt a walk down the hall I have to drag along a veritable life support system. The doctors tell me it will take time. That’s what they tell everyone here.

The clear plastic tubes are restrictive and bow outward like thin strands of spider webs leading to bags of clear fluids. The clear, plastic bags remind me of a pet store with a goldfish captured and tied off into an invisible plastic prison. I doubt half of the gold fish survive a week. And, here I am over six months in this plastic bag, and tied off. How long will I survive in this plastic bubble?

If you travel down along my side and follow the tubes, I am attached to a morphine pump. Happily, I can control the pump with a push button which will send up into my veins a warm, satisfying shot of the pain-killer every 20 minutes. I watch the clock, and if I’m conscious, press the blue button as soon as the 20 minutes are completed and I exhale with release. My mind is not cloudy but I hardly notice the nurses and doctors that come in and out of my room. They are bone white clad waiters asking me if I’m okay—“do you need anything”. The doctors huddle together, just out of ear shot, and look at me every now and again. They are concerned that I don’t talk to them or the psychiatrist; I do speak to the nurses, occasionally requesting some information or chatting up the attractive ones. Simply put, I have very little to say to the doctors, except “When can I get out?” They just smile and say something about physical therapy, which I take to mean not very soon.

The doctors say they have dug out the shrapnel and cleaned out the minute bits of dirt, concrete and plant matter. They remind me that I’m a very lucky person. I’m not too concerned. I think the drugs have something to do with that. I don’t feel much at all. The drugs have nothing to do with that.

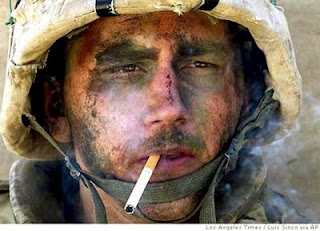

I can remember most of how I got here. I was thrown in the air by an explosion from behind. I bounced off the ground and landed in the dirt and concrete that was tossed up. I was wounded—couldn’t believe it. Someone grabbed me by my LBE and dragged me to the rear then onto a stretcher and tossed me into a Blackhawk chopper. All around me are walking wounded and the not so walking dead. As I lie on a stretcher, I get simple and assured smiles from the medics. Some of the guys in my unit come by and look into my eyes with envy. I can’t hear them over the sound of the beating rotors and the ringing in my ear. I read their assuring mouths. They scream at me: “You lucky dog”. I have the “million-dollar wound”, they say. My war is over. I can only look up at them, smile and nod. But I know my war is just beginning.

I’m taken off the battlefield by a dust-off—a Blackhawk empty of everything except the wounded, the dying and the dead. The medics check me over and roll me until my back is visible. They prick my arms with needles, trying to get the IV’s flowing. And, finally the sweet blanket of morphine knocks out the world. Eventually I get stuffed into a white jet with a big red cross and the Marine insignia on it. That’s kind of like putting a peace sign on one side of your helmet or rifle. We are laid out around fifteen vertical and four deep across the bulkheads on both sides of the aircraft. There is no room for any others. They will have to wait for the next one. The other wounded soldiers don’t make much conversation except drug-induced murmurings or futile calls for their mothers. I don’t remember much of the jet ride except an angel of a marine nurse, who periodically looked into my face and smiled. She was red-headed and soft light surrounded her beautiful face. That could have been the drugs.

We arrived at Fort Sam Houston and I eventually made the Chinook ride to Fort Kessler, in Biloxi. After about six months, I finally get the surgery. The surgeons told me the procedure was a success, but I have my doubts, since my right leg has so far eluded my mental commands.

After some time at Ft. Kessler, someone, a general I imagine, made his rounds and pinned a purple heart on my pillow. I was in the arms of Sister Morpheus so I didn’t notice. When I woke it was there, mocking me. After some time, while others weren’t looking, I unpinned the medal with George Washington’s cameo frowning at me, felt the heft of it in my hand and, embarrassed, threw it into the garbage can. I have refused to tell them that my back and leg wounds are from friendly fire—a short round of mortar fire that flipped over and over with a deadly, surreal noise and fell just behind me. The short defective round threw hot shards of metal, scorched earth and missiles of tree splinters flying forward into my prone and exposed body. Remembering this, I pushed the morphine pump again and set myself off to another world—where the nightmares belong. The nurses come by to take a look and just sigh at my continued reticence.

When ordered to Panama I was as naïve as the rest of them. Being a forward observer for the 5th infantry Division, I was deployed to Panama for training just after the May 1989 Panamanian elections. The jungle training school was a month of heat exhaustion and I came out the other end of it missing 20 pounds. After jungle training, the hot days dragged on and after securing some local leave, I began to leave the compound as often as possible.

As I sat and drank beer in the local bars, the news agencies reported the U.S. hopes for an election that would replace Noriega with their own people. Anyone could see that. The Panamanian public was apathetic knowing that one dictator would replace the other regardless of U.S. influence. When the elections were completed General Noriega stood as the winner. Within a week the elections were deemed null and void by the Bush administration and instantly Noriega became an enemy of the U.S. Despite the animosity between the Noriega regime and the Bush administration, we soldiers were free to roam the country as long as we were back to base before curfew. We ignored the political situation and went about our business—most of it with the Panamanian people. Some of my fellow soldiers were Panamanian and had families close by Fort Clayton. They joined the U.S. military to get citizenship and then move their families to the states.

At the time I had no foresight into what would become a brutal U.S. invasion of Panama, nor did I expect that, for the first time, I would learn to love. And, ultimately as it turned out, I would kill the very woman that I loved. Before this deployment I would have told you such a thing could not happen. But it did and did for many of us on the ground during the invasion.

That June was as hot and humid as Panama gets. During the mornings I pulled guard duty. The Panamanian sky would open up like a purple ribbon across the horizon. The strange sounding birds would start a sing-song chorus and it seemed to me that the peacefulness of those mornings could never turn into war. I was delightfully ignorant. On my excursions out of the barracks I often went to Panama City and drank Panama Cerveza or Soberana with members of my unit. The beer was cold and cheap. We would get drunk and get loud. The locals gave us long disapproving looks and shook their heads. After some time I became embarrassed by my behavior. And, bored with my bunk mates, I wandered outside of the city to the neighboring El Chorilla neighborhood. I was told by many friends in my unit that it was a poor, stinking heap of a place. They dismissed it outright without ever having been there. They said to me: “If you want to get mugged or catch a disease, then that’s your place.” Soon after these admonitions, I visited the neighborhood, weary at first, but eventually found a tragically poor but vital community, full of an everydayness of hope and life.

I met Maria for the first time at a public park, cleared out of the encroaching jungle, half-way between Fort Clayton and the El Chorrilla neighborhood. Maria lived in a crumbling concrete walk-up with her sister and her sister’s children. The apartment was two rooms with a small kitchen. Running water was intermittent. Most residents collected rainwater from the building’s broken cistern or collected jugs and cans of water from the stream. Just outside of Panama City, this large community was one of the poorest on the isthmus and had been named for a large creek that once fed the neighborhood; that was before the Canal was built. Now all the washing was done at what was left of the stream on the other side of a strand of trees behind the park. I fell in love with the place, made good friends and played with the kids who roamed about in groups. And, well, maybe that’s because Maria was there nearly every day.

For a few lonely soldiers, including myself, the park was a respite from barracks living. For the poorest of Panama’s citizens the park was a necessity—a place of commerce and escape from the rigorous demands of everyday living. This simple park was their playground and their economy. Tin-roofed, or palm-thatched shacks encircled the park’s grassy center. These were like vacation homes for the many families that took the time and effort to build them. Many people would spend lazy days in the shanties during the hot dry season. There were wilting plywood tables covered with various goods for sale. You could buy your yucca or rice here. There were vendors selling DVD’s, home-made clothing and American T-shirts. There was a bristling trade for sexual favors which was mainly patronized by American soldiers, but ignored by everyone else. In the center of the park was a large Higa tree with its exposed, elephantine root system. The giant tree provided a playground and shade for families. The half-naked children ran around and around the tree in absolute joy, hiding among the large roots. There were families stretched out across the area searching for shade, picnicking and laughing. All this activity led to a palpable feeling of family and produced whatever permanence the community could devise. Despite being an American soldier, for eight months I became a transient resident of that community through my relationship to Maria.

Maria was nearly always at the park when the weather was acceptable. She tended to her sister’s children, feeding them arroz con pollo out of Tupperware stashed in a large home-made multicolored bag. I watched Maria feed the kids, watching them, standing legs apart and arms crossed under her breasts. Maria was average height, but a petite-looking, slender woman with a generous smile and a natural elegance. While I watched, I noticed that her hair was sun-burnt dark, and it framed a softly sculpted, friendly face. She was just tall enough that she could rest against my shoulder and the top of her head reach my chin. Her skin was a cinnamon color— a flavor.

As I watched, she was showing off her tea-brown eyes on an exceptionally hot, clear violet-colored day. She wore a light, thin, earthy colored peasant dress that stopped at her calves and gave a look at her light brown shoulders. From that day every chance I had to escape from the military compound I followed her through the park, won her attention and helped with the kids. In the succeeding months I managed to coax out her respect, and then a begrudging love. And it’s fair to say that I loved her as well.

Maria’s love was languid and patient, like the long days of the Panamanian summer. Often we lay side by side and nude on a large rotting hammock under the palm trees and half-way inside a shack lining the park. We were making love slowly and carefully, while watching out for the kids and listening to the day—something like the rustle of the palms and the sound of children playing.

Maria was as naturally quiet as the trickling creek. We spoke reluctantly and carefully to each other since her English was as bad as my Spanish. We communicated with a few words of Spanish, a few of English, a rustic sign-language, and an exchange of perfectly placed touches. We relished our siestas after making love in that heat and humidity, lying on the hammock, swinging side to side, the air cooling down our bodies. Time was as still as the surface of a pond. I was under a spell and felt none of the awful portent of days to come while lying beside her.

Just three days before the invasion, I walked Maria and the kids back to their concrete apartment block. Normally I would stay to eat dinner with the family. I had brought along some pork and vegetables I bought at the open-air market. But tensions where so tightly wound then that we were recalled to Fort Clayton and I had to leave early. I held onto Maria and we trembled in each other’s arms. I spoke to Maria gently. I lied to her and told her and her family that all would be well. I knew nothing about any particular military action but the eventual invasion was easy to suspect. To be honest, that day I knew in my heart that all was not at all well. In these past months I had never been accosted by any Panamanian, but the glares I received from Maria’s neighbors warned me to the danger lurking. I felt the desperate tension that hung in the air as all of the American soldiers disappeared from the streets. That night as I readied to leave Maria’s side for what would be the last time, I kissed her openly, in front of her family and hugged her. And I whispered to her ear the worst of lies: Mañana, Maria. God, how I wish I had never said those words; a soft promise of tomorrow that would never come.

That afternoon, after I returned from El Chorilla, we were locked down into the perimeter of Ft. Clayton. The commander, flanked by his lieutenants, briefed us on the situation and called on us to “execute our mission”. Execute? There was a general assault planned for every sector of Panama. Noriega was to be captured or killed and the PDF decimated. He barked at us, trying to entice a guttural, violent response. But, I have to say, the best part of us refused to respond to his call for vengeance. We couldn’t fathom an attack against an indefensible, small country, which held families for some and many friends for others. Aside from my specific mission as a Forward Observer, we were all told to support the coming invasion which was a combined air, sea, and ground assault upon the PDF and Dignity Battalions. Altogether, with the invasion force just off shore, we were a force of over 15,000 troops with the most advanced weaponry in the world up against an almost non-existent enemy with U.S. supplied M-16s and machetes.

After the briefing, I began to notice a tremble in my right hand. As I gathered my combat gear, cleaned my .45 pistol, and checked and rechecked my radios, the trembling subsided a little. I was using the latest technology for communications: an AT RF20 multiband transceiver which allowed me to communicate with ground, sea and air forces. I grabbed all the maps that were available, which were few and contradictory. I took along two grenades, my knife, and a field phone with a reel of commo line. The M-16 I refused. It only got in the way of my job. I did not have a GPS receiver. I had a compass, a red-lensed flashlight and old maps. After going over my gear multiple times, I rested on my backpack with the other forward observers. The tremble in my hand became noticeable and I covered it by holding onto my BDU’s. When they were all asleep I ran out to the gate, armed with only a .45 pistol. There was no way I could lay around and wait for the attack. I had to warn Maria and her family. Maybe they had friends or family in the hills. Maybe there was a place nearby to get cover from the horror I was sure was coming. When I got to the gate, all the guards where entrenched in dug-outs piled high with sandbags. They had M-60 machine guns, a couple of .50 calibers, frag and smoke grenades, and over my shoulder were MLRS rocket launchers, uncapped and ready to fire. I tried to get out. By this time Fort Clayton was locked down. I begged and pleaded but the others, they laughed at me. I was crazy and suicidal to want to get out. A scared, pimply private was ordered to escort me back to the staging area. He had the look of having fallen into a frozen lake although the temperatures were in the nineties.

It was no use. The perimeter was doubly surrounded by razor wire. The only way out was the front gate and that I had tried. I went to join the 13 foxtrots and saw they were mostly asleep but a couple lay there wide-eyed and scared of the unknown which was fast approaching. Soon Air Assault came barreling in, throwing up whirlwinds of dirt and some caught a ride with these cowboys of the 7th Cavalry. Some went to the mountains and others to key spots like the airport, coastline or Canal Zone. I was assigned to the area I knew best—Panama City and the surrounding area. After waiting in readiness for two days, we were released with the first sound of MLRS rockets going off and 155s blasting from miles away. It was around 23:30 hours on the night of 19 December when I left the gate of Ft. Clayton, and hurried to my assigned area just southeast of Panama City. They dropped me off about a mile from the park after taking some fire from La Commandancia. I was glad to be out of that coffin.

When I got there on foot, I was alone and found myself triangulated within site of the park, La Commandancia and El Chorilla proper. I threw away the field-phone and commo reel. It was too far from command to set up a hard-line to command. So far I had not monitored the radio. When I turned it on and canvassed the channels, the chatter was overwhelming. I turned to my command channel and turned on the encryption device. By this time I could hear and see the blinking lights of cargo planes and hear jets crossing overhead. The nearly silent whir of Apaches and the whine of the Specter gunships circling above. I heard mortars walking up and testing the way to Panama City as the US forces approached. I hid under some scrub palms and listened as the attack built. From my vantage point, just down a crumbling concrete path and into the tree line, I could see much of the attack. It was brutal and multiplying. And it was coming my way. Now I was scared. I was scared for Maria and her family and I was scared for my own sake. At times that night, I held my Kevlar to my head and got behind trees, as I saw 500 and 1000 pound bombs destroy buildings surrounding Panama City. At this time, the El Chorilla neighborhood stood silent, lights off and untouched. Most people were running inside the block houses for the little cover it offered and the area was filling with refugees from the City. Then it became personal.

My call sign was Hotel Tango 25—a quick reference to my unit and designated area of operations. When my commander sent down the first of my orders, I was relieved to hear the radio operator tell me to give a grid reference for an area into the jungle beyond El Chorilla. I could only guess what the target would be. After I climbed through the dense jungle, sweating and pulling hard off my canteen, I saw the target. I was almost ecstatic that it was an arms and fuel cache. It was unguarded and surrounded by a rusted chain-link fence. I called in the grid reference after I had backed off a good 100 meters and asked for one round from the 155s. I asked for a small correction after the first round then called on Arty to “fire for effect”. Then I moved as quickly as I could out of the area and back to my station on the tree line at the park. El Chorillo looked untouched. The moon was empty and I had not brought along NVG’s so viewing the park was a struggle. The fuel dump went up like lightning as 155s pounded it with about 15 rounds of high explosive. The sky became shadows for a few minutes with the light from the fires. Now I could see that El Chorilla was burning in places and small arms fire bounced off the concrete. For those few minutes of light I saw no one inside the park.

While hiding in dense scrub palms surrounding Panama City, cutting my arms on the bush, an intense firefight erupted right beside the El Chorilla buildings. The wild and desperate gunfire came from La Commandancia—the brass’s most favored target. The mortars began to rain down in and around the PDF compound. I could hear the thump of 20 mm and 40mm rounds and most were way off their mark. The U.S. infantry units on the ground were searching for targets and firing blindly. While getting as close to the ground as possible, I grabbed my radio and called up the 161st on the VHF and directed the mortar fire on La Commandancia. After a few rounds the compound was abandoned and utterly destroyed. The artillery had been listening to my radio traffic and opened up with 105s on the deserted position. I called command and appraised them with a sit-rep that the area was suppressed and emptied of any forces. Instead of stopping the meaningless fire on La Commandancia, command told me to find targets of opportunity in the El Chorilla neighborhood. My heart started pounding as I knew that Maria and her family were in danger. I did nothing but move up past the tree line of the park, duck behind a concrete drain and wait it out. I could see a few fires but the neighborhood looked practically untouched. I made a move to cross over to the building that held Maria but I was pushed back by fire from the concrete bunkers.

My left hand began to shake as I looked for a target on the maps which was sufficiently away from El Chorilla. Then the Colonel himself got on the radio.

“Hotel Tango 25, this is Tango 25 Actual. How you read, over.” My radio was too loud so I cut down the volume.

I answered in a whisper. “Tango 25 Actual, this is Hotel tango 25. Read you Lima Charlie, over.”

Then the major, eager to earn his Silver Oak leaf, sent the message that I had been dreading.

“Hotel tango 25 Charlie, need targets in El Chorilla area. Will send call sign of gunship over.”

My mind was racing and my left hand began shaking the map I was holding. My mouth was dry but I had somehow drunk all my water along the way.

“Hotel Tango 25 Charlie this is Tango 25 Actual. Call sign of gunship is Air Poppa 130. Do you copy, over.”

“Tango 25 Actual this is Hotel Tango 25 Charlie. Roger, I copy call sign “Air Poppa 130” over. Tango Actual, I have no targets in area, over.”

“Tango Hotel 25 Charlie…you had better find me some. We have intel that the enemy is hiding in El Chorilla area, over”

Then I broke protocol and pleaded. My voice cracked as I spoke into that handset.

“Sir, I have been watching this area for hours and have seen no PDF and no fire from area, over.” This was a lie. I had seen many people running to the El Chorilla buildings through the fire light, some of them shedding their uniforms and weapons as they went.

“Goddamnit, son. If I say there is a threat from there then there is a threat. Call in the grid to Air Poppa and get out of there. Do you copy, over."

There was nothing I could do except risk a court-martial.

“Roger, call in Spooky, Tango Hotel 25, Wilco”

I could see that the El Chorillo neighborhood was going up in flames. I had no way to see that Maria and her family were safe. Maybe they had left already. Then I had an idea.

“Air Poppa 130, this Hotel Tango 25 Charlie. How you read, over.?”

Immediately those boys circling the area in the C-130 answered and I could tell they were eager to get into the fight. They called themselves “Spooky” and “Puff the Magic Dragon”. They were able to decimate a complete grid square with two mini-guns and a 105 howitzer, circling from way above the battleground.

“Hotel tango 25 Charlie this is Air Poppa 130. Read you Loud and Clear. Ready for grids over.”

I was about 100 yards or more from the park, hidden half way inside the drain pipe, and couldn’t see much of it through the bush. I meant to call in fire on the park and spare El Chorillo as much as I could.

“Air Poppa 130, this is Hotel Tango 25 Charlie. Direct fire to grid square 743531. How read, over?”

Although I loved this little park area, this was as close to the neighborhood buildings as I was prepared to direct fire onto.

“Hotel Tango 25, this is “Spooky”. Read Lima Charlie. Can see you through Night Vision. Get out of there Hotel Tango, over. Standby for Puff , out.”

I backed a little more toward the creek and then “Puff, the Magic Dragon” came down with ferocity that only two chain guns can provide. Thousands and thousands of tracer rounds poured down in two uninterrupted corkscrews. I watched through the trees as the park, where I had met and made love to Maria, was plowed under a downpour of 7.62 mm rounds. After a mere 20 minutes, Air Poppa hesitated and then began a systematic sweep of the entire El Chorillo area. Spooky’s cannons reduced the buildings to rubble.

I called up to them.

“Air Poppa 130, this is Hotel Tango 25, cease fire, over.” I waited. I repeated. I called command. I waited.

They ignored me. I watched the show and was physically sick as an entire neighborhood of innocent non-combatants was buried under artillery, air to ground mini-guns, 105 howitzers, and mortar fire.

No matter how much I called into command to stop the fire, I was ignored. I took out my .45 and carefully aimed at the gunships in the sky going around and around spilling out death. I emptied my entire magazine and carefully placed the smoking pistol back in its leather holster. My left hand quit shaking.

I began to pull myself upwards and climbed a small wooded hill which remained outside of the park. The mortars were now going directly over my head. I skirted the park and finally reached the tree line on the other side. I lay down behind the concrete walking path and watched the terrible beauty of a modern war machine dispatch entire towns to small, chewed up, unrecognizable pieces.

I turned off my radio and lay just behind the tree line. I didn’t want to listen to the jovial tone as unit after unit scored devastating hits on anything standing. With the radio off, I imagined that I was out of this war and lay there, listening to the various sounds and sights of destruction that erupted around me. I listened to the mortars popping behind and to my right. They made a hollow sound as they passed over my right flank and splattered into El Chorillo. Then, as I tried to get up and head to the rear, lying in a push-up position, I heard a brief whistling noise and a then a constant whooping sound. In my grief, the sound didn’t register with me as danger, although I had heard it many times before in training. The mortar round fired by, most likely, the 161st Infantry was defective: a short round. It landed about 20 yards behind me and the shrapnel spread out in a blossom of hot steel. I heard myself grunt as the mortar tore through the trees and threw tiny bits of steel into my back and legs. It was the concussion that put me out, temporarily.

When I regained consciousness I was being pulled backwards by someone who had a grip on my LBE. I was covered in dirt and shredded plant matter. My face dug a narrow ditch in the earth and when we stopped someone was kneeling over me cleaning my face. They were speaking to me but I heard nothing. My ears were closed by the concussion and I could only watch his mouth move. I felt the stick of a needle and the medic nodded his head and held his thumb up in a reassuring signal.

I was lifted off the ground by a black hawk and felt weightless. I imagined that I was being lifted up to heaven until my ears, during the flight to the airport, finally registered sound. I heard the whup, whup, whup of the helicopter and I closed my eyes.

So, that is my confession. After months of trying to find Maria from a hospital bed, an old taxi-driver I knew from Panama City wrote back to tell me that she was uncovered, identified and reburied, along with most of her family, at Jardin de Paz—the garden of peace. He told me she was torn to pieces by bullets and buried in a mass grave where she died—the park at El Chorilla. She was eventually identified in the mass grave and some remaining family moved her. I thanked him. I couldn’t tell him that it was my fault, that I had killed them all. Her death and the deaths of her sister and children are my responsibility. I did what I was trained to do. I called down from the sky a dragon that snaked its way down to the earth and killed the woman I loved along with her entire family.

Maria and I were in love. At least I know I loved her and we made love like the world would end any day. And it did end. In the midst of our ardor, the circumstances of a US invasion into Panama led us to the depths. Eventually, after the invasion had destroyed our world, I was flown back to the world, alive but broken, and she turned up in a shallow mass grave in the park of El Chorilla.

I am not asking for forgiveness. That is something I can never receive since those that I loved and killed are all gone now. I merely wish to tell the truth—not the official version, repeated so often by the U.S. press pool--but the truth that we have stuffed away, buried, and hidden from the Panama sky.

Later I was to discover that we faced a mere 4,000 troops, many of whom abandoned their uniforms and weapons as the invasion began. The brunt of the attack would be borne by Panamanian civilians and a UN estimated 4,000 dead with thousands more wounded. During the US invasion, the El Chorilla neighborhood would become a killing ground as U.S. firepower rained down thousands of high explosive artillery shells, bombs, missiles, and bullets. It became an easy target for concentrated firepower and it was flattened. Thousands of innocent men, women and children were killed, wounded or disappeared and the neighborhood ceased to exist. The park was my doing; it was chewed up into an empty dirt field full of bloated, shattered bodies, animal carcasses and splintered wood. That night Maria and her family must have made that march across the street and into the park where they thought they were safe. Then I killed all of them—her—with one simple, ignorant, radio call to the dragon in the sky. In the next few days, the U.S. military simply bulldozed the bodies into a trench and covered them up as if they were a trash heap. All that remains are lies.

The nurse comes by and tells me that it’s time for dinner. She frowns at my indifference. They move me from the chair back into the hospital bed and put the TV on, ask me which channel and place a plate of food in front of me. I look at the food then I look at the nurse hovering around the doorway. I press the blue button again and wait as the morphine does its thing.

© JP Miller

Contact: Contact

JP Miller is an author and journalist. Among published works include The Deep Blue Goodbye in The Literary Yard and Born to Run in Southern Cross Review. His journalistic work can be seen at Potent Magazine. JP Miller is a disabled veteran and lives in the Outer Banks, North Carolina.

Home