Third Tour Nightmares

by JP Miller

Looking down at the smallness of the world from atop a mountain will put time and distance in perspective. Iraq was a world away. And, in the light and color of the hills, the sky really put a cover over my heart. The war lost its immediacy. I began thinking that maybe I should quit the Army and go to school. I started to read Thomas Wolfe again, joked with friends, and began to put off sleeping for hikes around the mountain. From the flat view of the desert to the elevation of a virgin mountain covered with a blue, smoky mist is quite a transition. Just days ago I was in the bright, powerful sun of a cruel and expansive war. Now, camping with friends in Asheville, I found myself at the pinnacle of a rock formation not far from the Blue Ridge Parkway. Up the long, winding trail to the peak was a small clearing where we pitched our tents. It was surrounded by smooth, worn tapering rocks and a few short scrub pines. On the hilltop, looking west, there was a sheer cliff. It looked down a good 80 meters into the uncertainty of the mountain fog and disappeared. It was autumn and as far as I could see from that hill were trees on fire. The red, orange and yellow leaves lit up the mountains like a quilted and patched blanket of flames. I was up here to escape the constant edge of the battlefield and to shake off some of the culpability. That’s what I told myself. But, the thought that I could somehow escape the fear that comes with combat on a hilltop was naive. And the ability to assuage my guilt with majestic views was laughable.

When I got back to the world after my second tour in Iraq, I was feeling pretty good about things. I had been promoted to E-7 and had saved all my hazardous duty pay. My girlfriend had left while I was gone, but for some reason I didn’t really feel bad about the whole thing. She was getting married to a friend of mine and I wished them well. My mother asked me why I whistled so much and commented on how well-adjusted I seemed “considering everything”. I bought a brand new truck and started partying with friends while keeping an eye out for girls. The Army didn’t want to see me again until my 45 days leave was up.

My mountain explorations took me back down the hill from the light and space—back to a world that I hoped had disappeared. And, after a few days, I lost sight of the beauty around me and closed the door to the world. My heart sank and I began to drink again—like I had done in Iraq. While waiting for missions we drank like we were dying of thirst, like the desert was closing in and a bottle of scotch was an oasis. We drank and fought. We beat the hell out of each other, trading punch after punch, punishing ourselves for our crimes. And out on a patrol we talked about drinking and getting drunk. We never said it but we all craved the sweet bliss of unconsciousness waiting for us back in the rear.

After only a few days back, I began to hike down the hill to a bar and drink until the doors closed then climb back up and pass out in my tent. I would sleep all day while my buddies trekked the mountain and swam in the small river below. While they got out of the bottle, I climbed back in and closed off the natural beauty that was around me. Just when I thought I was out of the desert, the whole thing pulled me back and covered me with sand.

I woke up one evening and when I unzipped the tent and looked out into the fading light they were all gone. Had I known they were going to leave? Was I supposed to go with them? The hangover was slight but the rapidly disappearing light made me feel queasy. It was the same feeling that I had in Iraq after the surge started—how nausea was a warning that the shit was coming and to keep my head down. The anxiety of waiting for something to happen, something bad, turned my stomach and head into knots. So, instead of waiting for tragedy, I went looking for trouble.

Again I hiked down the mountain to my truck. It was there, safe and sound, and I sat in the cab staring at the darkness and the bright stars that only a lonely hillside can provide. I walked to the bar and ordered a draft while I called a buddy on my mobile. I just wanted to make sure that they knew I was left behind. No answer. I tried someone else and still no answer. I didn’t think much of the empty phone calls and drank my beers in silence until the crowd arrived about 7pm. It was busy that night and the crowd got loose and loud and fights broke out occasionally. I played some pool with the locals and chatted up their girlfriends while they weren’t looking. I bought them beer so they put up with my presence until one wealthy college kid made a fundamental mistake. After beating me soundly on the pool table, he looked at me and laughed. It was like slow motion. I saw him bend backwards in an open-mouthed “Ha!” and taunt me with his pool cue. He poked me with the stick and said to me: “Hey soldier boy. Ever kill anyone?”

At first I didn’t answer. What was the point? These guys were younger and college students and didn’t have the wisdom that a war puts into your bones. I let it ride. But they all stood around the table looking at me as if I were one of their professors, waiting for the right words to write down. I felt like they were waiting for me to teach them something. Then I saw myself walk around the table calmly and grab the guy's Columbia down vest with my left hand. I watched myself pinch the back of his neck with my right hand and slam his head down on the slate pool table. His forehead and nose burst open with blood. The blood flew patiently around the table like the splatter of a mortar. Some of the blood sprayed on the girls who were watching and they hopped back examining their designer clothes. I let go of the guy, picked up a pool cue, spun it around and put the butt-end of the thing into his kidneys. He went down so fast his head bounced off the side of the pool table. He lay all curled up into himself, moaning, and I watched him bleed on the floor while the rest of the locals walked backwards. It was surreal. It was like that painting by Van Gogh with the pool table. The green felt of the table spread out like it was miles long, the lights had a halo and there were people standing still, holding their breaths. No one approached me and I backed out of that bar calmly.

Once outside the back door, I looked at my hands expecting them to be bloody but they were clean. My hiking boots had a rim of red around them so I knew it was real. The street lights glowed in golden halo rings. I thought about what I had done to that kid. It was like the first firefight on my first tour in Iraq. I shot a young man twice in the chest while clearing a building and it made me sick. I tried to patch the guy up and called for a medic after we cleared the rooftop but no one came and he just wouldn’t die. Again, the nausea came and I leaned against the building, vomiting until my eyes stung with tears.

I began the walk up the mountain, singing a soft cadence to myself “Left…left…left, right, left.”

On the way up the mountain no one seemed to be concerned with me. There were no police, no sirens, nobody. If they wanted me they would have to climb the mountain. No vehicles could possibly make the climb. I fell into my tent, buttoned it up and lay my head down. Sleep was what I needed most.

The sand of the desert was making that sliding noise. It sounded like jump boots slipping across the dry wadi. I couldn’t see anything except the darkness surrounding me until the eyes popped out. Six sets of yellow tiger eyes followed my eyes. They moved to wherever I looked and stared at me somberly as if pleading. I tried not to move but the desert wind kicked up the straps on my LBE. They flapped with the wind. And my empty canteen began to clang as if a metal button was tapping out signals.

The eyes began to come closer and I could see that they were them. Them. The ones I knew that I had killed for sure. The ones that fell like sandbags. The closer they came, the larger and brighter their eyes became. They pleaded with me to stop. They cried and blinked and circled me.

I pulled a grenade off my LBE and pulled the pin. The eyes stared at the grenade and I held it to my chest. And the eyes told me to release the spoon. I did and waited for the explosion to end all of this. The grenade was a dud. I threw it aside and the sand covered it up. I yanked off another grenade, pulled the pin, released the spoon and held it to my chest. I waited. Nothing. Another dud? I felt all over my uniform looking for another grenade and found them in the same place as where the others were hanging. I kept trying; one after the other, but the grenades would not cook off.

I woke up cold and alone. I remembered the nightmare and it took my breath away to recall the whole thing. The desert had seemed so real. I felt all over my body. It was intact. Not a touch of hangover bothered me. I climbed out of the tent, stood up and some sand fell off my clothes. My boots were clotted with sandy blood around the edges. There was a creek with a rocky, sandy edge that ran parallel to the path for some distance. I must have tripped and fallen on the way back up the mountain. I started a fire to warm myself and sat staring into the comfort of the flames for a long time.

While preparing to take a wash in the river below I wondered why no one had come looking for me after the bar fight. That kid I beat on was surely hurt. His nose was probably broken and a punch in the kidneys with a pool stick was painful as hell. The bruises would be large, purple and brown spots that were impossible to conceal. Maybe he was taken to a hospital. Maybe he was really hurt. Why did I do that?

I walked down to the small river bed, found a good spot and swam out into the cold water. Underwater I could see some fish and the clean smooth boulders. My dirty clothes were on the ground and some fresh clothes were draped across a branch. When I pulled my shirt over my head, I heard a cough or something like a cough. Then I heard a slight moaning noise like that of a sick puppy dying alone in the mountains. That sound really put the hook in me. It reminded me of the wounded Iraqis and US soldiers that I had seen take their last breaths. It got so bad in Iraq that I would eventually whisper to them “shut-up” and “die already.” That sound, that pleading moan, I could not tolerate.

The river was loud but I heard rustling in the woods and got dressed quickly. Then the feeling that I was being watched and ambushed came over me. I felt my face go red with fear. Of all the time I had spent in Iraq, the worst time was either waiting for a mission or riding in the Humvee looking out for an ambush. I had been through a couple and had lost some friends as a result. When the firing started, it was a kind of relief.

The woods were deep and the trees were beginning to change colors. I looked all around me but saw nothing except an endless stream and the sentinel trees protecting me. It must have been an animal. Then I remembered that there were bears here and I gathered my clothes. I began the short walk to my truck. I intended to go to the store and get some provisions as I had no intention of leaving the mountains yet.

While driving to the local Walmart I began to feel better. There was no reason to be so jumpy. I was back in the US and the war was a memory. Then a car backfired and I slammed on the brakes while diving under the dash for protection. Somebody said “incoming” and I covered my head. I felt around my body for a weapon, any weapon, but then realized I had brought none. The horns went off and people began to curse me. They were yelling out their car windows at me. I jumped up and got back into the flow of traffic.

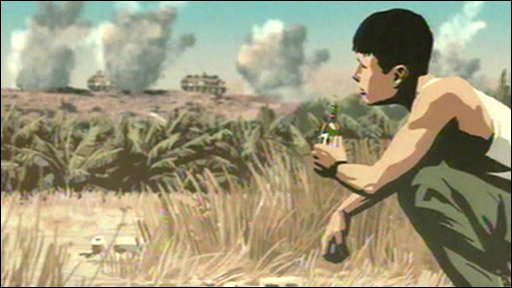

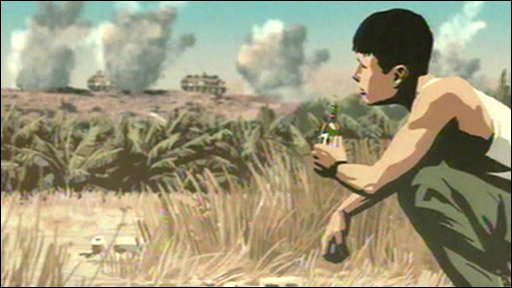

The Walmart was packed with people coming and going, carrying huge bags of things they didn’t need. When I walked in through the wrong door, the world bent upon itself again. Walmart was so big and long it curved with the earth. The long banks of lights glowed and the halos came back to me. I was really amazed at how much food, toys, clothes, electronics, and myriad other things were available. It was in perfect contrast with the emptiness of the desert and the poverty of the people in Iraq. Whereas in the desert going for water was a necessary step out into the open to survive, here water was bought and sold in pretty bottles. Braving snipers, mortars, and kidnapping, the locals would sprint to the neighborhood open water tap carrying whatever container they could find. But here, back here, it was a status symbol. Soccer moms carried two or three dollar clear plastic bottles of some designer water in their hands as they ran around the neighborhood to tighten their butts. I couldn’t help but think about the teenage Iraqi kids who sprinted to the water hole carrying large, white plastic containers, zigzagging across the broken, crumbled streets. These kids couldn’t carry a lot of water but they were the fastest in the family so they had to run the gauntlet.

When the halos disappeared, I went to get some MREs and some fresh fruit. And I bought the largest container of water they had. I bought a few bottles of wine, the largest ones that I could find. Running the gauntlet to Walmart was enough for me. I was inside the store for less than ten minutes when I felt the need to leave. The girl who checked me out was pretty and had such a bored look on her face that she resembled a manikin. When I went to swipe my check card, I noticed my right hand begin to shake slightly. I watched it stutter and so did the girl.

“Are you alright?”

She said this to me quietly but it seemed as if everyone in the store heard her. All the shoppers and workers stopped and looked at me and then looked at my hand. Only the quiet of the desert was as desolate as that store at that moment. Everyone knew. Knew what? Did they know about my beating of that guy in the bar? Did they know I was a soldier? Did they know I was a killer? I managed to leave with my purchases and climb into my truck. I felt better behind the wheel and sat there enjoying the solitude. The cab felt like a cocoon of silk that soothed my rapidly beating heart.

Driving out of the parking lot, I turned right and passed the Veterans Administration hospital. The big sign at the gate said “Welcome”. I had never been in a VA hospital since I was on active duty. When I had been wounded slightly on my first tour, I was patched up at a kind of giant balloon hospital. These mobile, temporary, air-filled medical facilities were in the green zone mostly, although one could be erected near a large battle in less than a day. They looked like tunnels of parachute silk. The soldiers came in one side and out the other. They came in as broken bodies and out the other side in body bags.

While driving to the parking lot below the hill, I came to a red light about fifty meters before the turn. The traffic was fairly heavy and I waited for the light to turn green. Cars sped through the street, probably on their way home after work. Then my right foot, securely on the brake pedal, suddenly moved to the gas pedal and pushed down hard. The truck jerked ahead as if it wanted to drive into the cross traffic. Immediately I pushed the brake with my left foot and the truck stopped, tires squealing. What the hell? I had to push as hard as I could with my left foot until my right foot gave up and relaxed. I turned into the lot all the while struggling with the urge to press on the gas pedal.

When I made the campsite after humping a heavy rucksack up the hill, I was spent. I was a jumble of nerves so I opened a bottle of wine and drank from the bottle. It was Chianti but I hardly tasted it before I finished the thing. I built the fire back up and opened another bottle. Sitting there, halfway in and halfway out of my tent made me feel like I was halfway in the world and halfway back in the desert. When the light faded and the fire gave off that yellow-white glow, I began to feel better. The wine was doing its job. I began to forget what had happened the past two days and started singing “Old King Cole” to myself. The simple rhyme of those marching songs can be a great comfort to a soldier, especially a soldier losing his mind. I got drunk as hell and was glad of it. The simple act of tilting that bottle was enough to sooth my sunken heart. When I went into the tent to sleep that night, I had no idea what was waiting for me.

There were militia coming straight at me with AKs and RPGs. Everyone beside me, my friends, were dead. The bodies were lying in the sand on their faces and the sand was washing over them. I was alone. I could feel it. Nothing is emptier than the desert at night. But they kept coming at me as I fired my M-4 at them. I ran out of ammo. Then I pulled out my 9mm and fired it until it quit. I looked for another magazine but there were none. They kept coming. But they didn’t get any closer. I had time. I had time to finish this. They were circling me and laughing. One of them looked familiar. It was the student I had beaten. He was laughing again. I looked at my 9mm and ejected the magazine. There was one round left. I slammed the magazine back into the pistol, pulled back the slide, and put the thing to my head. I pulled the trigger but it misfired. I pulled out the magazine, ejected the round from the chamber, and looked at the single brass bullet. I put the round back in the magazine, pulled back the slide and put it to my head again. Nothing. It would not fire. I tried my left hand but it wouldn’t fire. I kept squeezing the trigger but nothing would happen. The militias were on one knee around me. Laughing at me. And the sand began to take my lower body as I sat. I watched it crawl up my waist to my shoulders, to my arms, and to my neck, and into my mouth. I was choking...choking.

The tent was spinning when I woke. I couldn’t get my breath and my mouth was burning. I panicked as some sand spit out of my mouth. The grit ground and crunched on my teeth. When I remembered my dream, the whole of my body shook as I coughed. I grabbed my canteen and poured the water into my face. I choked on the water. When I finally quit coughing, my eyes were drenched with tears and I was grateful just to pull one decent breath. It was then that I knew this was no ordinary nightmare. I was losing my mind.

When I could steady myself I packed up my gear, doused the fire and started down the mountain. All that I could think about was the sign at the VA hospital. It had said “Welcome”. I almost ran to my truck carrying my fifty pound ruck. I threw it into the back of my truck and pulled out of the parking lot, hoping that my right foot would not betray me—that it would not push that gas pedal down again.

The VA hospital in Asheville was so full that I could hardly walk without bumping into another veteran or active duty soldier. Most everyone was walking on a cane or in a wheelchair or limping along. They all had a look on their face like this was the end of the world, like it was the edge of space. I nearly knocked over a soldier learning to walk on a prosthetic leg and I bumped into a vet being led by the hand down the hallway. He had a blank look on his face that told me “schizophrenia”. How did I know? Was I schizophrenic?

I made it to the urgent care center and gave my military ID to the nearest clerk. He asked me: “What do you need?”

“I need to see a doctor. I need to see a psychiatrist.”

There was no easy way to tell someone you need to make sure you’re not going mad.

“Now?” He said.

“Well yeah.” I said.

“What’s wrong with you?”

I really didn’t know how to answer that one. What is wrong with me?

“Are you feeling suicidal?”

“Well, no…but, maybe, does it matter?”

The guy didn’t even look at my face but asked me again if I was suicidal. I got the idea that if I didn’t say “Yes” – that I was suicidal – I wouldn’t be able to see a doctor.

So, I said “Yes. I want to kill myself.”

He looked up at me. He squinted as if to ascertain my condition in a single glance. He must have seen something. He told me to have a seat while he checked me into the system. I got my ID back and sat. The wait must have been over two hours long and by the time they called my name I was bouncing off the chair. I had no idea what lay behind that white steel door. But I was about to find out. And when I did I would never want to walk into a VA hospital again.

The nurse checked my vitals and ushered me into a small room that had two chairs with a desk and a computer. The walls were bright white and dented in places. There was fist-sized hole behind the door and I wondered who had had the nerve to do that. I sat for another hour at least. When the doctor came in, I was about to leave and go get a bottle of something.

“Mr. Barnes?”

The doctor never looked at me but sat at the computer and typed away. He was slight built and had a small bald spot. He looked tired and moved in a slow crawl except for his fingers which pounded the keyboard. When he spun around in the chair, I answered.

“Yes. I am Jake. Jake Barnes.”

“What is your birthday, Mr. Barnes?”

I gave him my birth date and he said “OK, what’s the trouble?” And, I told him the truth about the nightmares. But something told me to leave out the times when I had seen the halos around the lights and heard noises I knew were irrational. Then I told him about the bar fight and how I had beaten that kid. This is what got his attention. He looked at me sideways.

“What about suicidal thoughts and plans? Do you have a plan to hurt yourself or someone else?”

Never had I been asked such questions. I didn’t know what the right thing to say was then and began to think that this was a mistake—that I would be better off up on the mountain. Nurses and staff passed me by and gave me a look reserved for the really sick. It was the same way soldiers know when someone is past their expiration date in a war zone. I had seen it many times. Good men would get that thousand yard stare and become quiet, like a stone statue. They would sit and clean their rifle, quit going to the movies, and stay in their bunks. Nobody would want to go out with them. They were left out of the patrols and the only mission they got was when the shit was flying and they needed everyone, especially a stone cold killer.

“Mr. Barnes? Did you hear my question, Mr. Barnes?”

I was stuck.

“Yes.” I said. “I mean no. No plans.”

“Well, Mr. Barnes, I’m going to call 1 East and turn you over to them.”

“What is 1 East?”

The doctor cleared his throat and looked at me.

“1 East is the psychiatric inpatient ward.”

I never expected this one. Coming to the VA was a day trip for me. That’s what I thought and had not considered that they would hold on to me and lock me up.

“Well, doctor, I don’t think I need to do that, right now. I mean, I have to get home.”

Before the doctor could answer, a pair of VA rent-a-cops appeared at the door to the room. They stood with their arms folded across their chests and looked at me with puzzling eyes.

Getting into the psych ward is the easiest thing in the world. Show up, tell the truth, and anyone can walk through those doors. The cops escorted me to the last ward on the bottom floor. 1 East. Going through the double doors was like magic. They rang the bell and the door buzzed and opened like I was parting the sea. It was a goddamn miracle.

When I entered, all my notions of freedom were lost to me. I was a ward of the Veterans Administration now. Some judge had been called and he faxed a sheet of paper that put me on 1 East properly. I was court ordered to stay until the primary doctor signed a release for me to leave. 1 East was filled to capacity when I took over a bed. There were old soldiers dragging their feet down the hallways, looking like zombies on a food run. There were a few women who sat around the TV and stared at their hands, heads down and out of it. The staff followed me with their eyes everywhere they took me for “in-processing”. They asked me all kinds of questions that I really didn’t hear. I was too busy trying to figure out how I had come to be here trapped in a cage with lunatics like me. They gave me pajamas—yellow ones with big letters on the back saying “1 East”. Everyone else had on red pajamas and I wondered what I had done to get the yellow ones.

The staff of a psych ward is a mix of professional liars: mad scientists and sickly sweet apologists who tell you how fucked up you are with a special smile reserved just for you. They are pill pushers who believe that chemicals can cure any ailment you can think up. They are behaviorists who tell you just to act this way and you will be this way. I thought to myself that Freud would turn over in his grave if he saw this circus act. But I was here for the long ride and it would be to my advantage, if I wanted to leave, to learn what is was they wanted to hear. Play along. The Behaviorists would love that.

After four hours of processing I was shown my room, or rather my bunk. And this is the thing that would bother me the most. I was in a tiny room with four other totally whacked out war vets who were mostly staying here because outside those doors only the street was left for them. They were solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short to this world. Thomas Hobbes would love that one. My bunk was the farthest one to the back. The others looked at me with a mild curiosity and I got the feeling I was the last person on earth. Their eyes were wild and their pajamas hung on them like they were scarecrows.

The nurses tucked me in and gave me some pills which I swallowed without asking what they were. They looked at me with sad eyes and sighed. I went to sleep thinking only one thing: how to get out.

The morning sun over the desert pushed me down on my knees. The light was orange, red and especially yellow. I held on tightly to my M-4. I could feel it. I could feel the ambush coming. I choked on the nausea and swallowed a mouth full of fear. It was them. They were coming for me. They were coming and I couldn’t move my body off the sand. I heard them first. That soft moaning sound of a dying soldier was coming toward me. Then I saw them. Them, again. Walking sandbags. They stood over me moaning and pointing at me. Me. They took away my rifle. They took away my grenades. They took my canteen and stripped me to my t-shirt. The sand was swirling around and around and it rubbed me raw. Then they tied my hands and pulled a blindfold around my eyes. But I could still see. One of them pulled out a sword. A sword? It was like a large machete and it pinged with the sound of sharpness.

One of them held my head and another swung that sword at my neck in a flash of brilliant yellow light. I could hear the sword come down and through my neck. They were laughing. Laughing at me. They swung the sword again and I begged the thing to work. They swung again and again, over and over, but the sword seemed to miss each time. They went back to their moaning as they swung that blade. I could feel the sand in my hair and on my face. It found my eyes and my ears and my mouth. They fed me the sand and I swallowed it in great handfuls. They swung again.

Waking up was not an easy thing to do. There are stages to waking from a drug-induced sleep. First, I could hear. Then, I could feel. Then, I could see. And then I could think. I remembered the dream and cried a little, just a whimper that turned into the moaning sound. My eyes and ears were full of sand and grit. I made it to the one bathroom we shared and washed my face and ears. The sink was full of sand. I washed it down the drain before a nurse could see it. There was no way to know if it was daytime or night. The windows were blacked out and the only light was artificial. It was quiet and all my cellmates were snoring and farting, making noises that drove me out into the hallway. Here I sat against the wall with my hands over my face until a doctor saw me. She took me to her office and examined me thoroughly. She poked and prodded, asked me a few benign questions, and told me to go to the pharmacy. It was med time.

At long last I saw a psychiatrist. They brought me into a room where there was a board of doctors, pharmacists, social workers, counselors, psychologists and a ripe old man who must have been in his eighties. They sat around a table and invited me to sit at the end. I sat. Then the questions came at me. I was still under the spell of the meds and couldn’t really verbalize my answers very well, but I tried. I knew most of all that if I wanted to leave this place, I would have to lie and lie well.

“Mr. Barnes. How are you feeling this morning?”

So, it was morning and I presumed light outside. Just this knowledge made me feel better. Knowing the sun came up once again was all I could hope for. I answered their questions like only a madman can do. I told them I was fine now and it had been a mistake. I didn’t belong here. They laughed at that one. I knew they had heard it all before. But, I kept up my lies. You start with one lie and build on top of it other lies. One after the other, you speak, until you have built a wall of lies. And, you keep repeating those lies.

“I am good.” I told them. “No problems. I’m fine”

The way they looked at me was like I was a tiger in a cage at the zoo, pacing back and forth. I was just hoping that one of these times I will pass an open door and go through it quickly. The old man spoke finally.

“I hear you are having nightmares. Can you tell us about them?”

No fucking way was I about to tell them about my nightmares. One word of that and I would be here indefinitely.

“They have stopped. It must have been the meds because I feel better now. It really helped. I slept like a baby.”

“OK, Mr. Barnes. You need to be candid with us. We can’t help you unless you tell us the truth. So, do you feel depressed, anxious? Are you seeing or hearing things?”

Oh boy, I thought to myself. Here it comes. I’m schizophrenic and they know it. How can I stop this slide?

“No sir.” I said. “I feel better since I slept. I can honestly say that I was just tired and I am not experiencing any abnormal or irrational thoughts.”

“What about this fight that you were in? Do you remember that incident?”

“Oh that. It was just a scuffle at a bar. I must have had too much to drink.”

And then I knew what my savior would be. Alcohol. Blame it all on the alcohol. Yes, I drank too much and yes I need to go to AA, that’s all.

“I need to quit.” I said.

For thirty days I hung onto that lie like Superman. They would pack me full of drugs for depression, anxiety, personality disorders, schizophrenia, bi-polar disorder, PTSD, violent behavior, and drug dependence. I took Haldol, Seroquel, Invega, Amitriptyline, Wellbutrin, Thorazine, Prolixin, Navane, Stelazine, Trilafon, and Mellaril. Every kind of anti-psychotic drug they could dig up, I tried it. They gave me anti-depressants, anti-anxiety drugs, and anti-spasmodic drugs. Eventually, they talked me into ECT—electroconvulsive therapy, better known as shock therapy. I ran the gamut of drugs, therapies, counseling and isolation. After an ECT round, they would put me in the isolation room for a couple of days. It was better than staying in that room with all those lost souls and I was grateful for time alone. I went through day after day of this while they experimented on me like I was a rhesus monkey. And, I was proud of myself. Through all this I hung on just well enough to tell my lies: it was the alcohol.

When the therapies stopped, I was given a pair of red pajamas and up-graded to top monkey status. I sat in the dayroom like the other monkeys and stared at my hands. I ate the nasty food they gave me and I spoke kindly to the staff and patients like I was sincere. They finally decided on a cocktail of drugs and I promised to take them.

Finally, the day came for me to leave. I was lectured about the meds and told that I must take them. I was given the name of a place for AA meetings and assigned a social worker. She was an earnest young woman with a red face and red hair. I told her that I would see her regularly and not to worry. I was feeling fine. They let me change into my street clothes, gave me my belt and shoelaces back, and I waited for those rent-a-cops to come get me.

When they finally came, I made my most sincere goodbyes and stepped through that magic door once more. Out in the hall I walked with the cops to the main door of the hospital and said goodbye. I was just so happy to get out of there that I smiled and told them “thank you.”

I drove my truck out of the VA parking lot, tossed the meds out the window and went to get a bottle of anything. I picked out three especially good wines and drove to the parking lot below the mountain where I had camped. It was colder now and the hike up the hill warmed me up. I drank a bottle of Biltmore wine on the way to the top of that mountain. I savored the thing and felt the warmness slide down to my heart. The campsite was just as I had left it. It was empty and I could see that no one else had been there while I was locked up. After I collected some wood and started a fire, I began to put the tent back up. But something made me stop and I gave up on the tent. I wouldn’t need it anymore.

The end of this day was coming as the light faded and the fire started to glow, yellow hot. A wind kicked up and moved the trees down below. I could make out their sounds as they swayed back and forth, rubbing each other and swishing. The second bottle of wine was a Rothschild and it was a little bitter for my taste. I drank it down in an hour and opened the last bottle which was young Beaujolais and I loved this one. It was fruity and nutty and had an aftertaste of honey. When I came to the last drops of that bottle the fire was roaring and the warmth from both took over. I stood up and walked to the cliff edge as the fire popped and cast shadows on the rocks. I drank the rest of the wine and threw the bottle over the edge. Then I began to think about my nightmares.

During the entirety of my stay in the VA hospital I had nightmares. It was always the same three nightmares and I got used to them. I would wake up, roll over, spit out the sand and act as if I was on vacation. But I never told anyone about the nightmares. They were my secret and my reality. They were always there to remind me of my sins and to wash away my transgressions like confession. I thought of them—the sand bags—and how they would be coming for me this night; how the sand would cover me and wrap me in madness. I took one step to the cliff edge and then another. I thought how I was supposed to be back at Fort Bragg soon and sign up for another tour in Iraq. I wouldn’t be doing that one, not this time.

JP Miller is an author and journalist. Among published works include The Deep Blue Goodbye in The Literary Yard, Born to Run and Mañana, María in Southern Cross Review. His journalistic work can be seen at Potent Magazine. JP Miller is a disabled veteran and lives in the Outer Banks, North Carolina.

Home