A Weaver's Fable

by

Paul Holler

I am called Leto. I am a woman of great privilege, born into one of the finest houses of Samos. When I was young, I married and became the lady of another fine house. I bore three children there. One, a daughter, lived to marry. She is now the lady of still another fine house. I am sure she is well.

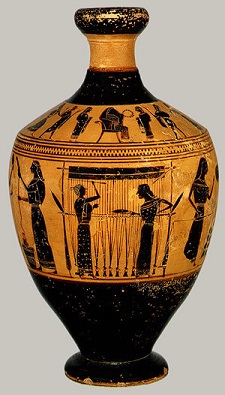

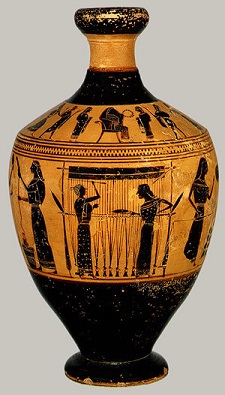

I had spent much of my life in a long room in the upper quarter of the house. A high window faced the courtyard and let in the light. Another small window at the opposite end of the room overlooked the road leading to the Agora. We worked in that room. Our looms stood along the walls surrounding the clutter of worn tables, drop spindles, shuttles, combs, baskets of newly sheared wool, heaps of washed and combed wool and finished cloth. Sometimes the other women of the house came by with talk of what passed in other rooms.

As the years passed, my husband and I grew apart. Our obligations as husband and wife had been discharged. My well had run dry. There would be no more children. My husband tended his business outside of the house and left me to tend to mine within the coolness of those walls.

But life within those walls had its compensations. Over the years we acquired slaves to help with the spinning and weaving. As my husband and I went our own ways, my slaves and I drew closer. Rhea and Ophelia had been with us for a long time and had become a part of our family.

Rhea came to us after our first child was born. She cost very little because she was blind. My husband reasoned that one need not see the baby's backside in order to wipe it. But I took pity on Rhea. When she arrived, I welcomed her to our house, took both her hands in mine, led her into the workroom and wrapped her fingers around a ball of wool. Its warmth cast a light on her face. I placed a drop spindle in her hand. She took it in both her hands and learned its shape and weight. I took a length of yarn that I had begun to spin, tied it to the spindle and let it dangle from my hands. Then I placed the yarn and the spindle in her hands. She felt its weight and, without my showing her, started the yarn spinning. As the yarn came into being within her fingers, her face changed from a frightened young woman to a child with the world at her fingertips.

Her first length of yarn was course and uneven. We were not able to use it on the loom, but with time she learned to spin the finest yarn I have ever woven. I have heard that the blind develop stronger senses to compensate for the one they lack. I suspect that Rhea can see more with her fingers than I could ever imagine. She can sit in the corner for hours, spinning cubits of perfect yarn from a world of her own. I know it must be hard to be blind, but there are times when I envy her.

Ophelia came to our house shortly after Rhea. My husband was able to acquire her for a small price, too. I have never understood why. She worked the loom as if it were a part of her. She would carefully set up the warp, strand by strand, from the ceiling to the floor, fastening each strand of yarn to the frame and weighting it at the bottom to pull it taut. In her hands the shuttle lost all form and carried the warp through the weft as if it were strands of cloud and not wool sheared from common sheep.

Sometimes Ophelia would look toward the front window. She rarely concerned herself with anything beyond her loom for very long. But one day she stopped working, walked to the window and looked out. I watched her and wondered what had drawn her away from the loom. She went back to her work after a few moments, but my own curiosity remained. I set aside my work and looked out the window.

The road to the agora was deserted. I thought that whatever had Ophelia’s attention had passed. But then I noticed a copper-skinned slave with a heavy bundle of wood strapped to his back.

I called Ophelia to my side.

“Who is that man?” I asked.

“It is Aesopos,” she answered. “He belongs to Xanthus.”

“Are you sure?” I asked. I could see that he was dragging one foot behind the other and that his back and arms were twisted. I suspected that they would have been twisted even without the burden he carried.

“Yes, yes, yes,” said Ophelia. “I have seen him many times in the agora.”

“You know of him,” said Rhea. “He is the one with all of the stories about hares and foxes and lions.”

“But he is so crippled,” I said.

“Is he?” said Rhea. “I always thought him to be thin and tough. Like good yarn.”

“I have always imagined him old and wise, like my grandfather,” I said.

Ophelia and Rhea laughed and I said no more about the man.

I had met Xanthus before. My husband knew him well. But I had never met Aesopos. I knew his stories. Everyone on Samos did. How could this wretched slave be that man?

I looked out the window and saw him again dragging himself and his burden toward the agora on the same road he had just followed away from the it. Again I watched him until he was out of my sight. Again I turned my attention elsewhere. But a moment later, there he was again struggling along the same path toward the agora.

What was he doing? Why would he keep walking the same path over and over with such a burden? I leaned out the window and watched him walk away from the house. Then he began to weave back and forth, the weight of the bundle pulling him from side to side. He came to a spot where the road slanted downward toward a ravine, lost his balance and went tumbling bundle and all.

“Oh, my!” I said. Ophelia looked up. Rhea put down her spindle and leaned an ear toward me. “Come with me.”

You may know that a woman may never leave her house except for the Festival at the Temple of Hera, but when I must I do. I gathered Rhea and Ophelia and covered myself in an old robe. If anyone saw me, he would take me for a slave and pay no attention.

Ophelia and I led Rhea down the path and, together, we ran toward Aesopos. He lay on the ground with his load of wood scattered around him. I took him in my arms and held him close. He let out a long sigh of relief. Then, suddenly, his body stiffened, he wriggled out of my arms and struggled to his feet.

“Are you all right?” I asked him.

He stood for a moment and breathed slowly.

“I’m all right,” he said in a trembling voice. “Uh, uh… I must go now.”

“You can wait until you’ve rested. We will stay with you.”

“No, no, no. I really must go now.”

He bent to the ground to gather the wood he had dropped.

“You are Aesopos, no?” I asked.

“Yes. I am Aesopos.”

“Why are you doing this?”

“What do you mean?” he said, tightening his brow.

“I have been watching you. You’ve passed by my house three times carrying that same load of wood. Why?”

He laughed a little, sat up straight and raised his hand as if he were about to say something. Then he waved it away.

“Why won’t you tell me what you are doing?” I asked.

“I ran afoul of my master,” he said slowly.

“What? How?”

“Well,” he said in a trembling voice, “most of the time, my master treats me well. He even comes to me for advice sometimes. But I have to be careful not to tell him too much. I mustn't leave him thinking that I know more than he does. He would not have that.”

“I do not understand.”

“Well, yesterday he told me about a business deal he’d made with his friend. I knew this friend. A little too well, maybe. People talk. I hear things. I knew he had cheated other people. I told my master this, but he did not believe me. Who was I to speak of his friend that way? But I stood my ground. I told him that I knew this man was dishonest and I could name all of the people he had cheated. My master told me to respect those who make the world turn. I stood my ground again. I told him that we all make the world turn. He told me that slaves like me turn nothing. I should have given way but I stood my ground. I told him again, this time in a loud voice, that he would be cheated by this man. I was sure of it. How many times had he come to me for advice? When had I ever misled him? Never! No matter. That’s when he told me to carry this bundle of wood back and forth until I learned my place in this world. One should never stand one’s ground before the man who owns him. When another man owns you, you have no ground.”

“That’s awful.”

“So you would not treat your slaves that way?” he said and looked at me with a wry smile.

“No,” I said, “I certainly would not.” Then I looked into his eyes. “You know who I am?”

“Yes, I know who you are. Your slave’s robe does not fool me. But you need not worry. I will not tell anyone.”

Aesopos saw two men coming around the bend toward us.

“I must go now,” he said. Then he hoisted his bundle onto his back and continued on his way.

I did not see Aesopos for days afterward. We returned to our work and, I am sure, he returned to his. But I could not get him out of my mind. One day, I saw that we had more cloth than we needed and could stop weaving for a while. My husband was not at home. There were only a few servants in the house. I put on my slave’s cloak, gathered Ophelia and Rhea together and set off for the agora.

I found Aesopos wandering alone, loading his sack with fruit and vegetables he’d bought for his master’s house. I lowered my hood and looked into his eyes. His eyes darted from side to side when he saw me.

“Aesopos,” I said. “It’s good to see you.”

He bowed his head toward me and looked around. Then he looked back at me and asked, “Can I be of service to you?”

“No, I do not ask anything of you. I only wanted to see if you are well. The last time I saw you, you were in a bad way.”

“I am well. Must go now,” he said abruptly. Then he turned away from me and disappeared into the crowd. We set off for home.

That evening, I sat in the courtyard, watched the sun set and thought. I had lived so much of my life in and about this house. Common slaves like Aesopos, Ophelia and even Rhea knew so much about the world outside these walls. There was so much I did not understand. But I wanted to learn.

The next day, I put on my slave’s robe again, gathered Rhea and Ophelia and, together, we made our way to the agora. Again, Aesopos was there, moving through the stalls and striking bargains with the merchants. He talked easily to them, but as soon as he saw me, he stiffened.

“Aesopos,” I said with my arms open and at my side. “It is good to see you again.”

“May I be of service?”

I thought for a moment and said, “Yes, you can.”

He bowed his head and said, “I am your servant.”

“You are many things. I understand you are a very wise man. But you are not my servant.”

He looked at me with a furrowed brow. Then he looked around and nervously shifted his weight from one foot to the other.

“There are things I must do,” he said. “Walk with me?”

“Yes.”

“I will lead your blind woman.” He took Rhea’s hand and began to lead her through the crowd. Ophelia and I followed them.

The four of us gathered in a tight circle and wove through the crowd. Ophelia and I stayed close to Aesopos and Rhea. The crowd parted for them as they always do for the blind and the lame. When we reached the center of the agora, we stopped at a stall where a man was selling figs. Aesopos barely spoke to the man but somehow agreed on a price for a large sack. He drew a coin from a pouch tied around his waist and slipped it to the merchant so quickly I barely saw it. The price was far lower than I would have paid. I looked at Ophelia. She was watching Aesopos, too.

At the next stall, Aesopos gestured to the merchant the amount of olives he wanted and the two of them gestured back and forth for a moment. They quickly arrived at a price. I watched Aesopos pay the man. The old slave had done well.

At the third stall, Aesopos again wove his shaking hands over a clay jar that had caught his interest, gestured a price, drew a few coins from his pouch and paid the man, all with one long movement of his crooked arm. Then Ophelia followed in his wake, picking out a clay jar of her own and bargaining with the merchant with her own hands. She, too, won a jar for our house for very small price.

Aesopos changed course and led us to the edge of the agora, where men gathered in small enclaves, each rapt in conversation. He was our shuttle; we his weft. We stopped to listen to a conversation between two men, one dressed in a fine white robe, the other in a merchant’s robe that was old but not worn out from work. I recognized the man in the white robe. His name was Alastor. He was a member of the council that made our laws. That was all I knew about him, but my husband spoke of him with great respect.

Aesopos stood listening and gripping Rhea’s hand. I stood behind them, taking in the whole scene.

“You know how it is with families,” said Alastor.

“Family and business should never cross paths,” said the merchant. “But they do. They must. How can they not?”

“Indeed, they do.”

After that, the conversation grew hushed. The quieter it became, the more their eyes tightened with earnest give and take. I could not hear what they were saying. But then the words “You must help me” carried from the merchant’s lips to my ears. I felt his gaze and knew that we were intruding.

“Let’s go,” I said tugging on Rhea’s sleeve.

When we came to the end of the agora, we bid farewell to Aesopos. The walk to the agora had tired Rhea, but there was a light in her face that would not fade.

“What a morning this has been,” she said breathlessly.

“Well, it was a good walk,” said Ophelia. “but I don’t think it was anything to be excited about.”

“But it was,” Rhea said. “Couldn’t you see what he was doing? Wherever we stopped, something was happening.”

“What was happening?” Ophelia asked. “I didn’t see anything happening.”

“Did you hear the goings-on between Alastor and the merchant?”

“We did not hear all of it,” I said. “Just that the merchant needed Alastor's help with a legal claim his family had against him. I heard the merchant say ‘You must help me.’”

“No, no, no!” cried Rhea. “It was Alastor who said that, not the merchant.”

“I do not understand,” I said. “Why would a man in his position need help from a merchant?”

“Because Alastor is a moneylender. And nobody trusts a moneylender.”

“I still do not understand,” I said.

“The merchant needed help in the courts with his cousin’s claim. Alastor needed help to keep his seat on the council. But, from how they sounded, Alastor needed the merchant’s help more than the merchant needed his. He has a lot of enemies on Samos because of all of his dealings as a moneylender. I do not know what bargain they struck, but whatever it was, Alastor got the worst of it.”

I was dumbfounded. How could I have heard so much of their talk and understood so little? I began to wonder what else had been happening outside my walls for all these years, things that could have harmed me or my house, that I never knew of? What else had I missed?

The next morning, I gathered Rhea and Ophelia, put on my slave’s robe and set off once more for the agora. The old slave was there, shuffling from one stall to another, striking bargains and listening.

“Good day, my friend,” I said.

“Good day to you too, my friend,” he answered in his slow chant.

He took Rhea’s hand and the four of us wove our way through the crowd. At certain stalls, Aesopos looked for things he needed for his master’s house. But at others he simply stopped and listened. I watched the goings-on at the stalls where there apparently were no goings-on. I was beginning to understand.

"There is something I must know, Aesopos," I said.

"Yes?"

"What became of Alastor?"

"It is a complicated business," Aesopos laughed. "First, the merchant was entitled to part of his uncle's estate when he died. The merchant's cousins did not agree and they shunned him. The merchant thought he was in the right, but he needed someone to advocate for him. That is why he went to Alastor. And Alastor was happy to see him. He was running to keep his seat on the council and needed support from the citizens. The merchant had some influence among the other merchants and his support could have made the difference. But Alastor represented the merchant's cousins on the council. He owed them his loyalty. And the merchant did not have as much influence in the council as his cousins. But he felt that he was right. But what chance did he have against Alastor, with his authority, or his cousins, with their influence?"

"So he lost his bid?" I asked.

"No. In the end, Alastor supported him, he got his inheritance and Alastor was reappointed to the council."

"How did that come about?"

"Because the merchant has a gift. He knows how to read the sky. He knows when the rain is coming and when a drought is at hand. There are some who say he can tell you when the ground will tremble. Alastor needed his help more than anyone because, if he knew what the merchant knew, he could use that knowledge for everyone's benefit. It made everyone forget he was a moneylender and not to be trusted. It made him a man of distinction."

We stopped in front of the stall of a merchant who was selling olives, dates and nuts. He kept watch over his baskets of produce like the father of a beautiful maiden shielding her from her suitors.

“Watch this,” said Aesopos.

The merchant took up a cudgel and looked down between his baskets.

“Hah!” he cried. “There you are!”

He raised his cudgel and brought it down again and again on a basket of figs, sending them flying and rolling over the ground. I could not imagine what the figs had done to him.

Then I saw a mouse scuttling from under the baskets, dodging feet and distancing itself from the merchant and his cudgel, who were in close pursuit. When it was over and calm returned to the agora, the mouse had gotten away with his prize and the merchant had ruined several baskets of figs, which now lay sprawled on the ground to feed the other mice. I pitied the merchant. But I admired the mouse.

“Now,” Aesopos said quietly, “Who is the more powerful of the two? The merchant with his cudgel or the mouse with nothing?”

“The mouse, of course,” I laughed. “And I would not say he had nothing. He is so small and quick. He made the merchant ruin his own stock and he got clean away.”

“But what about tomorrow?” Aesopos asked. “Tomorrow its size and quickness might not help it. It could end up in someone’s trap or in the belly of a cat. Who will be the more powerful then?”

I did not answer. I listened.

“There was once a gnat who was eager to prove himself against the most powerful creature of all,” Aesopos began. “So he flew off in search of a lion. He soon found one and challenged him to a fight. The lion only laughed and said, ‘You want to fight me? Ha! You are a mere gnat. How could you ever defeat me?’

“Then the gnat flew into the lion’s mane and bit his face over and over. The lion swiped at his own face with his claws but left the gnat unharmed. Then the gnat flew up the lion’s nose and the lion fell over on his side and struck at his own face with his claws until he was bloody. Then the gnat flew away laughing while the lion, defeated and ashamed, licked the wounds that the gnat had caused him to make.”

The old slave drew himself up to his full height, unfurled his crooked arm and pointed to the sky. For a moment, he ceased being a slave and became a man of distinction.

“But then the gnat, full of his victory, got himself entangled in a spider’s web. As the spider grew closer and closer, the gnat bemoaned his fate and wished he had not been so cocksure of himself.”

Aesopos smiled slyly. His wrist returned to its crooked form and he held it close to him as if to protect his stories, his wisdom and his mettle.

And we returned to our looms and spindles. Our daily routine settled back to its usual rhythm. On some days, we returned to the Agora to seek out the old slave, who always had a story tucked into his crooked wrist. But on most days we went about our work.

And then one day, my husband’s servant came into the women’s rooms to find me. He never came into our rooms. I knew of only one reason he would.

I simply asked, “How? When?”

“A few moments ago,” he said. “He collapsed. It was very sudden. One moment he was walking across the courtyard. The next he was gone. I am sorry to have to tell you this."

I dismissed the servant and returned to my loom. Rhea stood up, walked across the room as if she could see and put her arms around me. It was only then that I began to cry. And after a few moments, I stopped. I never cried for my husband again.

For the next few days, I did not leave the house. Ophelia went to the agora every day and came back with the village talk. Word of my widowhood had spread through the village and some of the older men were taking an interest. But I had no interest in them.

I told Rhea and Ophelia to pack up the looms and make ready to move them. According to tradition, we were to move back to the house of my birth. My father had died many years ago and the house had passed to my brother. He was happy to see me. I suspect it was my dowry, which was still quite large, that made my brother so happy.

A week passed after we moved into the house and the looms were not yet set up. We had no place to work. After a few days of passing the time in the Samian sun, I sought out my brother to ask him where we could set up our looms.

“Hmmm…,” he said, pursing his lips, “walk with me, Leto. There is something we must discuss.”

I walked beside him.

“I am glad to have you home, Leto,” he said. “I am very glad to see you. And, as you might know, we have seen hard times these last few years.”

“Oh?”

“You can help us, you know. You can help this house, our family.”

“Yes?”

“We have enough servants in the house. Your slaves would fetch a handsome profit. We will sell them.”

“You cannot sell Rhea and Ophellia!” I cried. “They are with me. They are my family!”

“They are with this house,” he said quietly, “and I am your family.”

I turned my back to him and marched into the courtyard. I wanted to bring the wrath of the gods down on him. But what god would come to my aid?

I sat down beneath the shade of a tree and thought. What could I do against my brother, the head of this house? I was small. I had nothing.

My brother and I did not talk for days after that. I remained in the house until the Festival of the Temple of Hera began. On that day, I left the house with my head held high in the finest robe I owned. I loved the Festival. The temple was built at the mouth of a great river. I followed the path from the river toward the Altar of Hera between the rows of high columns and the great sculptures whose form rose toward the heavens even as their marble held them to the ground. It was the most beautiful place I knew. They say that Hera was born here. That is one story I have always believed.

Standing at the Altar of Hera, I tried to summon her strength if not her presence. What could I do to stop my brother from selling Rhea and Ophelia? What could I bring to bear? There were the suitors Ophelia told me about. I could have convinced my brother that I was going to remarry and take my dowry to another house. But I had no interest in the suitors. If I had said otherwise, I would have been lying. I saw myself weaving a complex web with an open-jawed spider sitting to the side waiting for me to entangle myself beyond any hope of escape. No, a spider's web was not the answer. I needed to weave a bolt of cloth that would keep us together and safe.

I walked into the room where my brother was sitting and took a seat across from him.

“I understand what you must do,” I said.

“I knew you would see reason,” he said.

“We must talk.”

“There is no reason for you to be involved. I will take care of it.”

“Yes, but we must plan for what we will do when they are gone.”

“What do you mean?”

“Our cloth is known all over Samos and I cannot make it without my slaves. It made our house wealthy. Whatever house they go to will become wealthy. Yes, Ophelia will fetch a good price, but Rhea is blind. No one will pay a high price for her. And the money we get for them will be spent quickly. What will we do when that money is gone? We must plan for that time.”

My brother pursed his lips. “I will consider this,” he said. “We will speak again.”

I held still. Then I nodded to him respectfully, rose and walked away.

Rhea and Ophelia sat in the courtyard. I sat with them.

“They say that your brother wants to sell us,” said Rhea.

“It has not happened yet,” I said holding her hand. “You must trust me.”

The next day, my brother summoned me to his rooms. I walked in and sat across the table from him, my eyes wide open and my wrist outstretched.

“I have thought about your slaves, Leto. I have spoken with the merchants who trade in your cloth. Very high quality. Everyone says so. So I have decided that your slaves will remain here and make that cloth here in this house. We will need to have your loom set up in this house. See to it.”

I closed my eyes, let go a slow breath. I nodded obediently. I wanted to jump to my feet and cry out “Aha! I was right! I know what’s best for this house!” But then I remembered the gnat’s fate and held my tongue. Instead, I crooked my own wrist and held it close to my heart.

Copyright 2014 Paul Holler

Home