Transcibed by Frank Thomas Smith

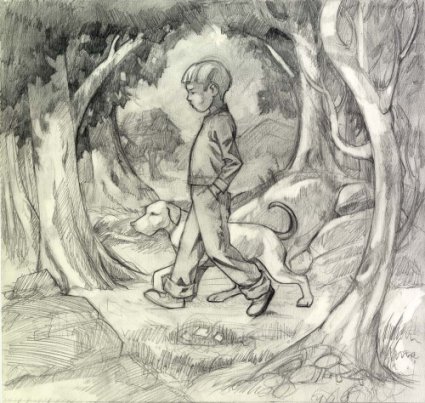

When I moved with my family to the country from Buenos Aires 14 years ago, we lived in an old house, once the core building of an estancia. There were ten acres of what was once farmland, but had turned into what my son, ten years old at the time, rather romantically and with his flair for exaggeration called a jungle. After a few days of snooping around in the “jungle” with his dog, he found a rusty old lunch pail. It had no lock on it, but it was rusted tightly shut, so he brought it to me to open, which I did with the help of a chisel and hammer. Instead of a rotted chicken leg, we found a...what should I call it? An essay, or simply an unfinished manuscript. Translated into English, it reads as follows.

We were four or five men, all about the same age, in our early forties, except for Dr. Bernard Lievegoed, who was in his mid-sixties then, and Lex Bos, seven years older than I. We were of different nationalities – I remember a Swiss who lived in Sao Paulo, Brazil, a German who lived in Johannesburg, South Africa. The others were Europeans, if I remember correctly. And I, an Argentine who was about to escape from my own country to Spain. Lievegoed and Bos were Dutch and we were in the Dutch city of Zeist, at the headquarters of NPI – the Netherlands Pedagogic Institute.

In spite of its name, NPI was – and still is – a consulting firm. Bernard Lievegoed, a physician, psychiatrist and university professor, was its founder. At that time, 1974, it was called NPI International, because of its intention to expand its network around the world. In fact, that's what we were doing there. Lievegoed gave a kind of introductory talk. He started by saying: "We are the lucky ones..."

I can't say that I had been “recruited” by Lex Bos, because keeping one's eye out for potential co-workers isn't the same thing. Furthermore, I probably asked him about joining NPI rather then he asking me if I wanted to. At the time I had what many considered a good job – as an investigator for IATA, the International Air Transport Association – and senior man in Argentina. But I was just at that age when grown men buy their first motorcycles and change wives. Furthermore, Argentina was being terrorized by leftist revolutionaries, specifically the Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo, which specialized in kidnapping business executives. My colleagues, the airline managers, had moved their offices across the Rio de la Plata to Montevideo, in Uruguay. You see, the possibility of being kidnapped for ransom and political statement was quite real. I felt that the work I was doing was not worth it. Something else influenced my decision; in fact, it was the main reason: anthroposophy.

The first time I'd heard of it was when I was a student in Germany. My future wife's aunt and uncle were anthroposophists and they told me about it during several conversations about things existential. What interested me about it was that it included the idea of reincarnation, yet was philosophically western; that is, it's founder and principal protagonist was Rudolf Steiner, an Austrian philosopher and esotericist.

I found work with Argentine Airlines in Germany without having finished my studies in business administration. After a few years, I was included in the airline's management training program and transferred to head office in Buenos Aires. By that time I was married and had a three-year-old daughter. We found a small house in a Buenos Aires suburb called Florida, at that time still heavily populated by German immigrants – including Jews and Nazis, who seemed to get along rather well there. The Nazis never admitted to having been of that persuasion of course. Three blocks from our home was the “Rudolf Steiner Schule”. My wife was German, so that was our daughter's mother tongue, and I of course spoke German from my time in Germany, so it seemed practical to send the child to that school...just to the kindergarten, I thought, because I intended to send her to an American or English primary school, English being, I felt, much more important for her future.

As it turned out, though, my daughter loved the kindergarten so, and the whole school atmosphere impressed my wife and me and so much, that we decided to let her continue in the primary school.

Steiner or Waldorf schools are based on anthroposophy, which reminded me of Aunt Trude and uncle Karl back in Frankfurt. But when I asked questions about anthroposophy in the Steiner Schule in Florida, I was referred to a priest in the Christian community – a church whose theology is based on Rudolf Steiner's teachings about Christianity. I soon found myself in a study group reading a series of Steiner lectures about “The Gospel of St. Luke” - in German of course. It floored me. I was born and raised Roman Catholic, but had moved away from the Church, mostly because of all the unanswered questions – the ones they answer by saying “it's a mystery” – which is, of course, no answer. Well, Steiner answered them all, or most all. Not only religious questions though.

Due to a crisis in the Rudolf Steiner School when my daughter was in the second grade, a group of parents took our kids out and started a new school, a new Waldorf school, as best we could. So I got more and more deeply involved – as president of the Board and teacher of English – one hour a day, so I kept my day job. I realized that the Waldorf educational system, based on anthroposophy, provides the spiritual and artistic warmth children need, something different than what the mainstream schools practice. And it works, the children are happy and they thrive.

Steiner also wrote a book about “the social question”. He was talking about his time of course, but there is much in it that is applicable today: Toward a Threefold Society. I read it during the Cold War, when the duality of capitalism-communism dominated the political-social scene. Here, I thought, was a “third way”. What also impressed me was that the same guy who went on and on about the spiritual world, initiation, science and religion, was also into politics and economics.

So when Bernard Lievegoed in Holland said: “We are the lucky ones...” and ended the sentence with, “...for we have anthroposophy, and are therefore morally obliged to help the others, who do not have it,” I was somewhat surprised that he included me in those who “had” anthroposophy, and it started me thinking about what that means. I'm still thinking about it and can at least say what he did not mean: proselytizing. Lievegoed knew that anthroposophy is not for everyone. After all, according to Steiner, “Anthroposophy is a path of knowledge which would guide the spiritual in the human being to the spiritual in the cosmos. It manifests as a necessity of the heart and feeling. It must find its justification in being able to satisfy this need...”

For me this meant answering certain existential questions, such as, Does life have meaning? (If not, what's the point? If so, what is that meaning?) I think that Rudolf Steiner answered these questions. The answer to the first question is: Yes! If proof is needed, well, just look around – at nature, where we see evidence of intelligence. Nature is intelligence, and very beautiful, and efficient, even when “red in tooth and claw”. So if intelligence exists in nature, some intelligent being or beings must have put it there. Nothing could be more logical. Spontaneous intelligence is no more possible than spontaneous life is. The only intelligent beings, and by that I mean thinking beings, are humans. Yet human beings do not create nature, they are born into it. Steiner maintained that nature is a solidified spiritual substance, that everything which exists in the physical world also exists (or pre-exists) in the spiritual world in spiritual form and spiritual beings are the artistic creators of the Earth and nature.

The main question, then, is whether a spiritual world that cares about human beings really exists. Can we assume that man, a thinking being – when thinking is a spiritual activity and therefore intimately related to the spiritual world – was created in order to live a life without meaning? Well yes, we can assume that. I, however, prefer to side with Kierkegaard and insist – if only to myself – on the absurdity of meaningless human life.

The next question we face is: What is that meaning?

We know that life is often – or mostly – cruel and unjust. But not always! It can also be gentle and beautiful, with traces of love. Steiner maintained that we are living on a planet, Earth, of love. That is , the mission of the earth is to become a planet of love. Obviously that will take a long time, and it's not a guaranteed outcome. It requires development – or evolution if you prefer – of consciousness and knowledge. And, most of all, freedom. Love is not possible without freedom. So, the reason, the meaning of life, is to develop love and freedom despite all the material and spiritual obstacles.

If we have convinced ourselves that life is meaningful and there is a spiritual intelligence behind it, then how do we explain the often horrible injustices occurring daily in the world, sometimes due to natural causes, but more often to human depravity? The only explanation is reincarnation. A dead and/or tortured child can hardly be the end-product of spiritual intelligence and justice. No, the child must have an ongoing opportunity to live and evolve – despite death! That can often only happen in a future incarnation on earth. Dostoyevsky's Ivan in The Brothers Karamazov famously does not kill God, like Nietzsche, that is, consider Him dead or non-existent, but rejects Him because he allows the suffering of children. Ivan did not consider reincarnation when condemning God and his holy Russian monk.

If there is reincarnation, there must also be karma – the retribution for the suffering you've caused – and compensation for the suffering you have undergone, but not necessarily during the same lifetime.

Then there is also “egotistical karma” - which provides practical reasons for helping the poor and for saving the planet. India, (for example) presently has 1.2 billion people, most of them poor. And other parts of the world, including Latin America, are also mostly poor. As long as such large majorities remain poor, there is much more chance of us being poor in future incarnations. Or having to live on a polluted planet. The possibility even exists of there not being a planet to incarnate onto. Endgame...?

The manuscript ends there. I do not know why it was hidden in a lunchpail and left in the valley of Traslasierra, so far from Buenos Aires. It is unsigned, so I don't even know who wrote it – in longhand, by the way. So I just call him “Z”. After translating it, I looked into anthroposophy myself, if only because Z was so enthusiastic about it. I found it quite interesting and have even devoted a section of Southern Cross Review to it. Z would be happy about that, I feel sure.

FTS

Home