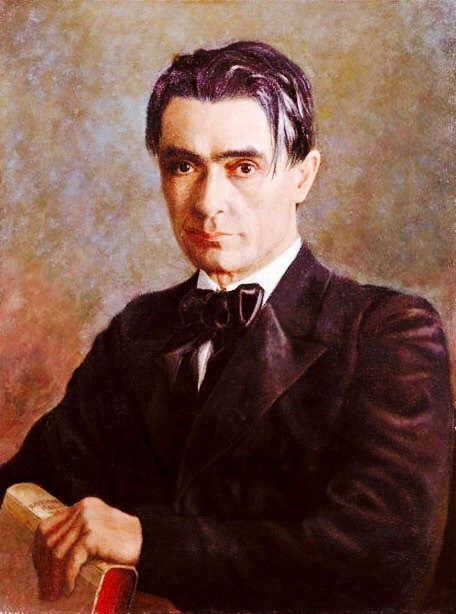

It may seem strange to include a commemoration of Rudolf Steiner’s Death Day in a newsletter that is devoted to the celebration of childhood, and new initiatives, and life in general, but even in the midst of so much life the Waldorf movement is obliged to face death. This article is an effort to understand this obligation.

The six-year period that extended from the spring of 1919 to Rudolf Steiner’s death on March 29, 1925, was filled with a rapid progression of triumphs — and tragedies. Among the tragedies were the fruitless efforts to heal Europe’s war wounds through the Threefold Social Order, the burning of the First Goetheanum, and Steiner’s long and debilitating illness. Among the triumphs were the refounding of the Anthroposophical Society and the powerful and prolific outpouring of the Karmic Relationships lectures. It was during this period that Rudolf Steiner also helped to found, nurture, and advise what he was to call the “Daughter Movements,” practical efforts to apply spiritual principles directly in contemporary society.

The daughter movements established vocations that made possible a unique path of modern Initiation. Teachers, doctors, priests, and farmers no longer had to retreat to mystery centers or ashrams to develop spiritually but were given the meditative exercises and practical challenges that allowed them to unfold their higher faculties while in the workplace. Waldorf Education, anthroposophically-extended medicine, the Christian Community, and Bio-Dynamic Agriculture have already, or will soon, celebrate their one hundredth anniversaries, and each has its own tales of success and failure. This article will focus on the special role that Waldorf education has to play among its sister movements.

It is important to note that the prequel to the celebration of one hundred years of Waldorf education involved a pitched battle over measles vaccinations in several schools. The conflict led to the collateral damage of a lawsuit brought by Waldorf parents followed by an embarrassing and viral article in New York magazine. Hardly had the US Waldorf movement recovered from that debacle than it had to face the insuperable challenge of a pandemic and school closings that coincided with Steiner’s Death Day in 2020. The celebratory AWSNA national conference in June was canceled, and in most respects the festival year fell flat. What might the daughter movements learn from this? [ AWSNA=”Association of Waldorf Schools of North America” ed.]

Perhaps we are mistaken when we try to celebrate the anniversaries of the daughter movements one at a time. It may be more helpful to regard the six miraculous years between the spring of 1919 and the spring of 1925 as a a single temporal gesture guided by the Time Spirit Michael. No less importantly, we should recognize that the period from 2019 to 2025 has the potential to be at once a recapitulation of the 1919-1925 era anda point of departure for the next hundred years. We must also be aware that these six years have the potential to be a time of unraveling. A few poor decisions and hasty compromises and the spiritual impulses that guided Rudolf Steiner in the twentieth century may be weakened or undone at the same breathless pace with which they were activated a century ago.

The direct spiritual guidance of an Initiate can persist for one hundred years, after which it fades from its embodiment in books and institutions and must be revitalized by individuals who have made those teachings their own. In this respect, the years 2019-2025 offer the final possibility of drawing upon Rudolf Steiner’s teachings. As of March 29, 2022, we stand at the half-way point in this six-year recapitulation. Significantly, it was at the precise mid-point of the six-year period during Steiner’s own lifetime (March 16, 1922) that misjudgments about the viability of the Threefold Social Order led to the financial ruin of the Waldorf Astoria Cigarette Factory and the termination of other efforts of economic transformation that he had helped to found. And that occurred with Rudolf Steiner still alive and well!

Every moment of the next three years will cast its light or shadow over the next century of endeavors founded by Steiner. Unfortunately, the way Waldorf institutions, the eldest of the daughter movements, have navigated the turbulent waters of the past years foreshadow hard times ahead. Going forward, the relationship of Rudolf Steiner to his Daughters may look much less like The Twelve Dancing Princesses and a lot more like King Lear.

What’s in a name?

In an oft-quoted interview on a 1955 broadcast of See It Now, the commentator Edward R Murrow asked Jonas Salk, developer of the first polio vaccine, “Who owns the patent on this vaccine?” to which Salk responded, “Well, the people, I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?” Nearly four decades later, this question might have been posed again as the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America transmogrified the term “Waldorf Education,” and later “Rudolf Steiner Education,” into Service Marks.

Rudolf Steiner once said that institutions created by human beings have a lifespan that parallels the “biblical” human life span, i.e. seventy years. As it approaches that threshold, the corporation, or not-for-profit, or association should engage in its own dismantling and share its resources and expertise with younger endeavors. Through such a “death and transmigration” the spiritual impulse underlying the older institution may be revitalized in a new and youthful body. As the 1990s approached and the worldwide Waldorf movement attained its seventieth year, the time had come for such a metamorphosis so that the Michaelic Sun-impulse carried by existing Waldorf schools might expand into more diverse directions. On the dual pretext that it was “protecting Rudolf Steiner” — particularly from the Internet attacks of the Waldorf Critics’ List — and that it was ensuring that “Waldorf” would never become generic term like “Kleenex,” AWSNA pulled down the shade and drew the light more tightly to itself.

As it happened, the 1990s were the decade during which the first charter schools cultivating Waldorf educational principles were being founded. It was also the time that the Internet not only extended the reach of Waldorf’s opponents, but also enhanced the resources and networking power of some of Waldorf’s most passionate adherents, among them countless American homeschoolers. At the very moment that the impulse of Waldorf education was ripe to cross the threshold of its transformation, the North American Waldorf movement was ready to adapt to new forms and directions and reach families from a broader sector of society.

How did AWSNA respond to this spiritual turning point? By contracting, excluding, and holding the Service Mark in a rigor mortis grip. For nearly thirty years, AWSNA’s apparatchiks sent reams of threatening letters to charter schools, public school districts, and even Facebook groups that were attempting to expand the scope of Rudolf Steiner’s educational impulses. The heroic efforts of Kim John Payne in his battle against bullying Waldorf schools were strangely paralleled by AWSNA’s bullying Waldorf schools. It is ironic to realize that Steiner was himself opposed to calling the original “Free School” in Stuttgart a “Waldorf School,” because he felt that the name would evoke images of billboards promoting cigarettes. In Steiner’s eyes, “Waldorf” already a commodity; he might be amused to hear the sanctimonious tones with which AWSNA speaks its Name.

The Service Mark may indeed have served as a life support system in the Association’s dotage, giving it both power (to accept and reject school candidates) and glory (“We own the Service Mark!”). However, it does not seem to have had any helpful effect on declining enrollments in the independent Waldorf schools, nor on the diminishing number of new independent schools forming in North America. In those areas, at least, the torch has clearly been passed to the schools practicing Waldorf education in the public and homeschool spheres. There are other Association missteps that are beyond the scope of this article but which I explore in my lecture course Does Waldorf Still Matter. However, there is one more destiny-laden error that relates directly to Rudolf Steiner’s death day.

The Portal of Denunciation

As it crossed from the first hundred years of Waldorf education to the next hundred years, AWSNA posted on its web page a statement that signaled a recognition, however unconscious, that Rudolf Steiner’s direct help to the independent Waldorf school movement was ending. This statement was the denunciation of Rudolf Steiner’s “racist statements.” It was composed in a tone of such sophomoric certainty and moral superiority that it all but cried, “You’re fired!” to the spiritual beings who nurture Waldorf education. With this (later mysteriously retracted) sentence, the independent Waldorf school movement in the United States accelerated the severance from Rudolf Steiner’s life and work that will very likely come to a not-so grand culmination in 2025.

As I indicated earlier in this article, Steiner’s direct influence must ineluctably wane over the next three years, so this severance need not be regarded as a failure. What a failure, however, is that that this portal of denunciation was established not out of spiritually-imbued understanding, but rather out of conformity to influences in many respects antithetical to Waldorf education. The AWSNA conference of June, 2021, in which Anthroposophy and Rudolf Steiner were rarely mentioned and the adjective “Waldorf” was mostly codified as “Eurocentric,” exemplified the spiritual impoverishment that is likely to hold sway in the near future.

Although there certainly was some sincere idealism and earnestness behind the denunciation, it also served as yet another distraction, masking the spiritual emptiness that underlies AWSNA and many of its member schools in the twenty-first century. Taking a stand for Social Justice is easy in today’s media climate— just plug in the terms and concepts and acronyms that others provide, and you are woke. Working out of Anthroposophy is far more demanding, calling for clear thinking, individual judgment, and the struggle to be — awake.

Indeed, every time AWSNA takes up a new social justice cause, it means more meetings and required workshops for faculty, and very likely a new staff position in the school: DEI Coordinator, BIPOC Rep, Cyber Civics Director, LGBTQ Liaison, and so on. And this is in addition to the plethora of staff already in place: Advancement, Development, Enrollment. The more that AWSNA schools strive to be centers of Social Justice, the more they look and act like bureaucracies. With such a top-heavy structure, and with so little attention going to the pedagogical concerns of teachers, parents, and even students, we must concur with Yeats’ phrase, “The center cannot hold.”

Small is beautifull

With all of this in mind, I would like to suggest how the Waldorf movement may appear when the current three-year grace period comes to a close.

The unsustainable corporate model of the AWSNA member independent schools will lead to the closing of smaller schools and the hollowing out of the larger “established” schools. Having constrained the role of their class teachers and elevated academics over Imagination, many schools will be Waldorf in Service Mark only. No longer supported by the living impulse of Anthroposophy, they will be “legacy schools,” basking in their achievements during the independent schools’ Golden Age of the 1970s and 1980s, but out of touch with the needs of the children of the twenty-first century. The most committed anthroposophists among the faculty will have mostly been fired or retired, and while one or two teachers in a school who have tried to make Steiner’s path their own will continue to do some good in their constrained setting, they will be a disappearing breed. Because their schools are no longer supported by the spiritual world, they cannot, in turn, support the spiritual striving of their teachers. And this, in turn, means that teachers who continue to work out of Anthroposophy are doing so out of a genuine impulse of freedom, not because it is on their job description. For the most part, however, the type of idealistic and spiritually striving young people who joyfully became independent Waldorf school teachers in the twentieth century will now be drawn to biodynamic farming, the Christian Community, or work in Camphill villages. 2025 will mark the long “beginning of the end” for AWSNA and its institutions.

As of this writing, there are sixty public Waldorf schools serving over 15,000 children. By 2025 that number will nearly double, and by 2030 “Waldorf” will be perceived by academia and the media as a public school methodology and will have far greater impact in the United States than the AWSNA membership schools could ever attain. The degree of spiritual support that public Waldorf schools may receive will depend less on their teachers and more on the caliber and inner life of their administrators. The strongest and most cohesive public Waldorf schools are guided by administrators who recognize the crucial role of Steiner’s methodology in the Waldorf classroom and respect the striving and initiative of teachers who find ways to bring it to life within the public-school setting. At the same time there are administrators who have little interest in, or even antipathy towards, the spiritual foundations of Waldorf methodology. Through their opposition they, too, will have a role to play in the expansion of Steiner’s educational impulse into the public sector. In the present three-year period, these schools stand at the “end of the beginning.” They are likely to attain their own Golden Age mid-century, and by the last third of the century, at age 70, will be ready to pass on their resources to their successors.

And who are those successors? Although the pandemic lockdown that commenced in the spring of 2020 threw many Waldorf schools into a state of panic and shortsighted responses, there were two groups of Waldorf practitioners that weathered the storm with equanimity. The one group included the thousands of homeschoolers whose children were already at home, and the second group was composed of the online Waldorf classrooms that did not have to scramble to plug into glitchy Internet services like Zoom and Google Classroom because they were already adept at distance learning. The unfortunate confluence of AWSNA’s pressure on its member schools to eviscerate the Waldorf curriculum in the name of euro-cleansing and its sudden celebratory acceptance of computers and mobile devices as learning tools led many parents to search for alternatives. This, in turn, has contributed to the founding of “homeschool pods” and “micro schools” serving families who, for the most part, want their children to receive a “real” Waldorf education, rather than the simulacra being offered in all too many schools. So many experienced Waldorf teachers and committed Waldorf families have joined or even helped to found these centers that we can speak of a ”Waldorf Diaspora,” the sort of migration of peoples that very often marks a new spiritual/cultural tipping point. One need only look at the “Jobs Listings” in this newsletter to recognize how many such endeavors have begun, and how rapidly their enrollments have grown. For many of these first adapters, such community schools offer an opportunity to teach in the spirit of “applied Anthroposophy” described by Rudolf Steiner as the basis of Waldorf education. For others, it means the possibility of working more deeply and effectively with smaller classes and providing the individualized attention that children’s paths of incarnation necessitate. The flexibility and mobility that such smaller schools possess gives them the responsiveness so needed in our tempestuous times. It is likely that many such schools will be established on the grounds of biodynamic farms and vineyards, anthroposophical clinics, near Christian Community chapels, and in Camphill villages. That is to say, Rudolf Steiner’s eldest daughter will take up residence with her younger sisters, and her new home will become the community school. And it is no less possible that such schools could be founded in neighborhoods in America’s inner cities. The hand-wrenching and justifiable guilt to which Waldorf schools subject themselves concerning their mostly white populations would be easily overcome by moving their campuses to urban locations with populations of color. The micro school model provides such a possibility.

If the mission of an independent Waldorf school depends on the spiritual life of its teachers and that of a public Waldorf school on the inner striving as of its administrator, then a great deal of what transpires in the Waldorf community school movement will depend on the inner path of its parents. Since the turn of the century there has been a dearth of parent education throughout the Waldorf movement as schools quietly covered their spiritual foundations. It is to be hoped that the families actively engaged in forming these new schools will also be diligent in their work with Anthroposophy. The hundreds of online and community schools that will arise over the next decades will spread the Waldorf impulse quietly throughout the continent, like a homeopathic remedy. Although Waldorf homeschooling has been a reality for decades, in its new iteration it marks the birth of a third stage of North American Waldorf education that is likely to take on a multiplicity of forms throughout the twenty-first century and reach its apogee at the threshold of 2100.

The best step for the shrinking independent Waldorf and the thriving public Waldorf schools to take right now would be to connect with local homeschoolers — even disaffected former school parents — and offer low-cost classes and activities to their children. Such a program has been in operation at the Yuba River charter school for several years and is exemplary in its scope and organization, while the Moraine Farm independent Waldorf school offers a homeschoolers’ program that is imbued with arts and crafts. Such programs are not only of mutual benefit in the here-and-now but will also make for a much more graceful transfer of a school’s resources and accumulated wisdom when its own mission has come to an end. For the next three years, in preparation for the century to come, may the Waldorf school movement “be busy being born” and, no less earnestly, “busy dying.”