There is nothing secret about anthroposophy. An enormous literature on the subject exists, including many books and lectures (more than 6,000) by Rudolf Steiner, published in German. A relatively small portion has been translated into Spanish, but what is available is more than sufficient for anyone who desires to be well informed. Literature by other authors also exists.

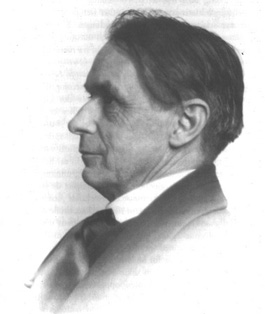

As anthroposophy is intimately connected with Rudolf Steiner, it will be convenient to say a few words about him before going into the material itself. Steiner was born in 1861 in what was then a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, then became Yugoslavia and is now Croatia. His father, a hunter by profession, was chief of a railroad station in a small rural town. Steiner was a gifted child, so his parents later moved close to Vienna so he could continue his studies. Aside from his intellectual capacities, he had other gifts. He could “see” elemental beings in nature, for example. When, however, he realized that no one else shared these clairvoyant experiences, he decided to remain silent about them.

After graduating from the Technological University of Vienna, he obtained his doctorate in philosophy from the University of Rostock in Germany. He worked for several years in the Goethe archives in Weimar, where he edited Goethe’s scientific works. (It isn’t widely known that Goethe was a scientist as well as Germany’s greatest poet.) Goethe made a profound impression on Steiner, for in him he found similarities to his own way of thinking. For example, Goethe proposed his theory of the “Urpflanze” (primal plant), from which, according to him, all vegetal life originated. He described this Urpflanze to Schiller, another great German poet, who remarked that it was all very interesting, but no more than an idea after all. Goethe replied: But I see this idea.

During his time in Weimar, Steiner wrote his “Philosophy of Freedom”. Although this is a purely philosophical work, Steiner later said that it really contains anthroposophy, only described in a different way. Afterwards he was editor of various literary journals in Berlin, until he was discovered by the Theosophists, his future wife, Marie von Sivers, being one of them. There Steiner found people to whom he could speak openly about his esoteric knowledge and experiences. He lectured regularly at the Theosophical Society and was eventually named secretary general of the German branch of the Society.

The split came when the theosophical leaders declared that Krishnamurti – then a ten year old boy – was the reincarnation of Christ. Steiner said this was nonsense. Whether he resigned or was asked to do so isn’t clear, but in any case he took most of the German members with him and formed the Anthroposophical Society. When he was older, by the way, Krishnamurti denied that he was the reincarnation of Christ and went his own admirable way.

Over the course of the years Steiner wrote and gave many lectures about diverse subjects: education, medicine, agriculture, religion, science, the arts, the social question, spiritual development – even the life of bees. There is hardly a subject that he didn’t analyze at one time or another.

Rudolf Steiner died in Dornach, Switzerland – headquarters of the Anthroposophical Society – in 1925, a little over a year after the first Goetheanum, the building made mostly of wood that he designed and worked on for ten years, was destroyed by arson. He was only 64 years old when he died and there has been suspician, but no evidence, that he was poisoned. The second Goetheanum, made of poured concrete, stands on the same spot today.

The Nature of the Human Being

The human soul is studied in psychology and religion, the physical body in medicine and physiology. In Freudian psychology the soul is no more than a biological function of the unconscious. The spirit is left unattended. But it wasn’t always so. At a ninth century Church council, it was decided that man consisted of body and soul, and not the trinity of body, soul and spirit. Since then soul and spirit have been essentially synonymous. This is obviously a grave error if in fact the human being has a body, soul and a spirit. In order to affirm this, we will have to define the difference between the two.

The physical body is the material element that we see with our physical eyes. And the soul? If I stand in the open here in Traslasierra and gaze up at the star-filled sky, I will experience a feeling of awe, even happiness. These feelings are functions of the soul. But then if I begin to ask myself what the stars are made of and why they’re there at all, and here comes the moon: beautiful, my soul says, but my spirit wonders how long it will take to cross the sky and if that crescent shape isn’t formed by the earth’s shadow. This function, thinking, is an attribute of the spirit, the I, the immortal, self-aware, individual component of the human being.

Now let’s complicate the situation somewhat and enter into more detail. The physical body is composed of the same substances as its environment: minerals, chemicals, liquids, etc. But if it were only that it would lie in bed like Frankenstein’s monster before getting the electric shock. It has life, and that cannot be explained by chemical formulas, or electricity. Let’s call this component the “life or etheric body”, which plant and animal life also possesses. But what plants do not possess is the “astral” body, closely identified with the soul. Animals and humans on the other hand do have an astral body. Animals are conscious, have sensations, experience pain and joy, hunger and, above all instincts. But, despite having various degrees of intelligence according to species, they do not think and aren’t self-aware. In other words, they have no individual I. Only the human being possesses this component.

[c]

[b]

[a]

[a¹]

[b¹]

[c¹]

Physical body

Life body

Astral body

< I >

Spirit-self

Life-spirit

Spirit-man

Human

Human

Human

Human

Animal

Animal

Animal

Plant

Plant

Mineral

During the course of evolution the I works on the astral body in order to transform it into a more elevated vehicle – denominated “Spirit-self” in the above diagram. It works on the life body to transform it into the “Life-spirit“ and, finally, it will transform the physical body into the “Spirit-man”. The latter two transformations are relegated to the distant future, so distant that these transformations will occur during future incarnations of the earth itself. We are still occupied with the transformation of the astral body – with lesser or greater success, depending upon the individual.

REINCARNATION AND KARMA

Now, to complicate things even further, we will say a few words about reincarnation and karma. A few days ago I read in the newspaper about a ship in Africa carrying a cargo of children kidnapped or sold in one country to be re-sold as slaves in another. This reminded me of Dosteyevsky’s “The Brothers Karamazov”, when Ivan, one of the brothers, says that he cannot believe in a God who permits children to suffer. An even if he existed, Ivan would reject him. This is the best argument I know for reincarnation and karma (the law of destiny). How do we explain the fact that often the good and the innocent suffer and the evil prosper? There are two explanations. Either the suffering is the result of actions in a past life, or new karma is being created and the suffering will be compensated for in a future life. There’s also the question of evolution and development. It is generally accepted that more complex organisms develop from simpler ones over the ages. And what about the human soul? Shouldn’t the same law hold true? There is a spiritual evolution – an evolution of consciousness – as well as an organic one. From incarnation to incarnation we strive to develop. Of course environment and genetics play a role in determining whether or not we are successful. If genius could be explained genetically however, the children of geniuses should also be geniuses. They are not. We all know from experience that siblings – even twins – are almost always very different personalities.

According to Steiner, after death we experience our past life in temporal reverse, and must experience the suffering we caused in others.

EDUCATION AND THE SOCIAL QUESTION

The relation between Anthroposophy and Education is exemplified in the numerous Waldorf schools and kindergartens that exist worldwide. We will not go into the Waldorf educational method here, as that is being done by the teachers in the meetings with parents. However, education, Anthroposophy and the social question have much to do with each other. Just think: the first Waldorf school was founded for the workers of a cigarette factory. The founder, the owner of the factory, wasn’t an educator. He was much more interested in Steiner’s social ideas. Here’s an example from Toward a Threefold Society:

“This book must assume the unpopular task of showing that the chaotic condition of our public life derives from the dependence of spiritual/cultural life on the political state and economic interests. It must also show that the liberation of spiritual life and culture from this dependence constitutes an important element of the burning social question.”

By “spiritual/cultural life”, Steiner is referring, above all, to education, which was originally in the hands of the Church and was then taken over by the political state, a necessary historical step in order to make education available to all. However, persisting in state control of education in a time when it is no longer necessary is destructive, if not fatal. We all know that the Argentine school system is in chaos. We tend to blame economic conditions for this. Of course the schools here are under-financed, of course teachers are paid miserable salaries. But did you know that in the so-called first world where enormous amounts of money are invested in public education, the school systems are also in a state of continual crisis? Steiner maintained that the principle cause of this chaos was, in his time, the dependence of the school system on the political state and economic interests. In other words, that the teachers were not free to teach the children in the children’s own interests. I maintain that little has changed in this respect.

All this raises a lot of questions, like: someone’s got to control what the teachers do. If not the state, then who? But why should anyone control the teachers? Who knows better than they, who are with the children every day, what their needs are? Especially in Waldorf schools where the same teacher stays with the group through the entire primary years. Of course the college of teachers of each school must exercise some control. If a teacher is doing the wrong thing or maybe shouldn’t even be a teacher – it happens – then that group must take the necessary action.

This is one of the most important innovations in education, which has been practiced exclusively by Waldorf schools: that the teachers must be responsible for the schools administration and direction. Here’s Rudolf Steiner on this point:

The administration of education, from which all culture develops, must be turned over to the educators. Economic and political considerations should be entirely excluded from this administration. Each teacher should arrange his or her time so that he can also be an administrator in his field. He should be just as much at home attending to administrative matters as he is in the classroom. No one should make decisions who is not directly engaged in the educational process. No parliament or congress, nor any individual who was perhaps once an educator, is to have anything to say. What is experienced in the teaching process would then flow naturally into the administration. By its very nature such a system would engender competence and objectivity.

It is often difficult for parents, school boards and other officials to understand and accept the fact that teachers are not employees, and that they (Board members) are there to support, assist and advise the teachers and not to give them orders. Once this is comprehended and the spirit of solidarity and freedom enters the community, the school will flourish.

Another question involves financing. If the state doesn’t control the schools, can it still be expected to finance them? The money to finance schools in any country comes from the productive institutions – industry – of that country. It makes a detour through the state in the form of taxes. The state then distributes a portion of those taxes to public schools and therefore considers that it has the right to oversee what the schools do with that money. Perhaps it would be unrealistic to expect the state to act otherwise. The funds for education could, however, be paid directly to a non-governmental educational organization, which would then distribute them to the schools. Or, if it is not that unrealistic to expect the state to do otherwise, it could finance the schools and at the same time insure the teachers’ right to educational freedom. All this is only a matter of changing the procedure once the decision has been made to free the schools from state control – which could be done in a democratic society if enough people want it.

Nowadays, when it is recognized that the state is incompetent to manage industry, it’s curious that this same state is judged competent to manage education – an area more important than industry, because without education there would be no industry.

The Tripartite Society

This idea of free schools was a part of Steiner’s concept of a threefold or tripartite society. Education suffers because it is dependent on the political state. The political state suffers because it is dependent on economic interests. Does anyone doubt this? The name of the game in politics today is to make laws that the economic interests want and think they need. Today just about all governments are pushing the free market ideology. Without defending or criticizing free markets, we should nevertheless ask what they have to do with human and civil rights, the defense of which is the legitimate function of the state?

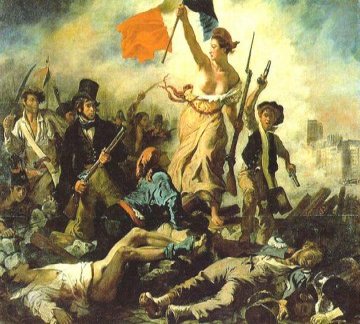

The motto of the French revolution was Liberty, Equality, Fraternity – a beautiful motto. But the government the revolutionaries imposed failed when the motto became Liberty, Equality and the guillotine. Their error was trying to organize a unitary state containing all three elements. Liberty is a characteristic of the spiritual/cultural sphere, as explained above. Equality is a political concept: all citizens have equal rights. The state can and should guarantee rights, but it should not be able to restrict freedom in the process.

And what about the third element: fraternity? We only have one sphere of social activity left, and it would seem difficult to attribute fraternity to the economic sphere. But if we look at economics more closely, we will see that it is quite correct to do so. Economic activity consists of three elements: Production, distribution (wholesale, retail) and consumption. In the production process goods are produced in order to be consumed. And who consumes them? Mostly those who did not produce them. Therefore we have one group, producers, working to make goods for others, the consumers. This is essentially a fraternal process. Of course if you ask anyone in the productive sphere why he works, he will say he works for money. Well, this is a problem of consciousness and the way things are organized. They could be organized differently. Steiner suggested that Economic Associations of representatives of Producers, Distributors and Consumers be formed. These associations would make the decisions relating to the economic sphere, for they are the ones active in it.

Centrally planned economies, such as the communists attempted in the Soviet bloc, China, Cuba and elsewhere, are eminently inefficient and lead to an excess of state power. Capitalism is efficient, but it leads to social injustice. Furthermore, the so-called free market is never really free, because the producers control it. They plan all right – for their own benefit. But if all three basic elements – producers, middlemen and consumers – met in associations, they could do the planning required to benefit society as a whole and still leave the market relatively free.

Another problem is the ownership of the means of production. Nowadays most industrial power is in the hands of a few holdings. The big guys are consuming the little ones. It is almost as though Karl Marx’s theory was coming true: that those with the most capital would eventually absorb those with less capital until one huge capitalist unit ruled the word. The Marxist solution to this was to turn the means of production over to the state. That failed miserably. We should remember, however, that Communism was a reaction to Capitalism’s injustices, which have not been resolved. The means of production, capital, should be in the hands of all those who actually do the producing – not anonymous shareholders.

The basic concept of the threefold, or tripartite society is that the spiritual/cultural, the political and the economic spheres of society should each enjoy relative autonomy, and that none should dominate the other. It could be objected that this is a nice idea, but no more than that. Steiner said otherwise. He maintained that the human being, consisting of Body, Soul and Spirit, that is, threefold, needs a society that is also threefold: the spiritual sphere in which his potentially free spirit may develop; the rights sphere where his soul feels the justice and injustice of society, and the economic sphere where his physical needs are produced.

A Philosophy of Freedom

This is the title of one of Rudolf Steiner’s earliest books. It is purely philosophical and therefore may cause problems for those who have no knowledge of that branch of thinking. I taught the subject for ten years in the Teachers’ Training Seminar in Buenos Aires and it took me half that time to realize that since most of the students had only the vaguest notion of philosophy (my own notion being somewhat less vague), it would be better to start with a general history of philosophy and get to Steiner later. From then on I had the impression that the students (and I) understood better what it was all about. That was a twenty-hour course and we don’t have the time to do that here, so I’ll just assume that we’re all philosophers.

“Is man in his thinking and acting a spiritually free being, or is he compelled by the iron necessity of purely natural law?” This is the first line of the book and it is the question Steiner will try to answer using philosophical arguments throughout. He also writes that “we are dealing here with one of the most important questions for life, religion, conduct and science.”

In order to answer this question, the concepts of dualism and monism are elucidated, dualism being the separation between us and the world around us. That is, if I observe any object in nature, a tree let’s say, I feel that I, the subject, am looking at an object, the tree, which is separate from me. This is a barrier that we erect as soon as we have consciousness – we become conscious of our antithesis to the world, the universe appears to us in two parts: I and the world. The striving to bridge this antithesis constitutes the spiritual striving of humanity. To be able to do so would constitute the monism we are seeking. The question is how.

According to Steiner, the answer can be found in thinking, which he considered to be a spiritual activity. Put simply, the argument is that if we observe our own thinking, we are overcoming the duality of subject vs. object in that the subject – “I” – is observing something which is completely of its own making: the object: “thinking”. Therefore, the subject and the object become one. If this is possible, then it is also possible for objects outside of myself. When we observe the physical object “tree”, we are seeing only a part of it. The other part, the idea “tree”, is lacking. The chairs you are sitting on certainly exist physically. But before they existed someone had the idea “chair” – the carpenter or designer, someone, or the chairs couldn’t exist. And we can share this idea “chair” with the carpenter. And the tree? If the tree exists physically, the idea “tree” must have existed previously. Therefore the whole tree consists of its physical manifestation that we observe with our eyes and the concept or idea “tree” which we can observe by means of thinking.

“We can find nature outside us only if we have first learned to know her within us. What is akin to her within us must be our guide. This marks out our path of inquiry. We shall attempt no speculations concerning the interaction of nature and spirit. Rather shall we probe into the depths of our own being, to find there those elements which we saved in our flight from nature.”

Are there limits to knowledge? Steiner seems to say that any such limits are self-imposed and that the object of knowledge is merely relative to the perceiving subject. “As soon as the I, which is separated from the world in the act of perceiving, reintegrates itself into the world continuum through thoughtful contemplation, all further questioning ceases, having been a consequence of the separation.” This seems to me a clue as to what kind of thinking is meant here. Certainly not to the usual thoughts that come and go willy-nilly, but what Steiner calls something more profound: “not a shadowy copy of some reality, but a self-sustaining spiritual essence…that is brought into consciousness for us through intuition. Intuition is the conscious experience—in pure spirit—of a purely spiritual content. Only through an intuition can the essence of thinking be grasped.” In this sense, the physical organization, i.e., the brain, can have no influence on the essential nature of thinking. Of course the brain is necessary for thinking, just as a piano or other instrument is necessary for playing music, but such instruments – and the brain is an instrument – are not the essence of music.

In answer to the question posed at the beginning: whether the human being, in his acts and thinking is free or not, Steiner says finally that a true philosophy of freedom does not consider man as a finished product, so it considers the dispute as to whether man is free or not (now) to be irrelevant. It sees in man a developing being and only asks whether the stage of the free spirit can be attained during this development.

There is very much more in “The Philosophy of Freedom” than can be discussed in these few minutes. Anyone who is interested in what freedom is and in Rudolf Steiner’s philosophical concepts which led to his later writings and lectures of a more esoteric nature, will do well to read it carefully. To close this subject, I think the following words appropriate: “Hence, every person, in their thinking, lays hold of the universal primordial Being which pervades all people. To live in reality, filled with the content of thought, is at the same time to live in God.”

Anthroposophy and Religion

The word religion is derived from the Latin “re-ligere” = reunite. In this sense of reuniting the spiritual in humankind with the spiritual in the universe, anthroposophy is religious. It is not a religion however, nor is it associated with a church or confession, but it recognizes all religions as being true it their own way. Steiner placed enormous importance in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. In his books and lectures on this subject, he explains Christianity’s essence and most of its mysteries in a way quite different from the teachings of the traditional confessions. A study of Steiner’s basic works, followed by his lectures on this specific subject, can open the reader’s eyes to the meaning of many so-called mysteries and give him or her a new appreciation of Christianity, one she never knew existed.

I would like to emphasize here that anthroposophy is not taught to the children in Waldorf schools. Steiner himself insisted on this. Otherwise the schools would be considered sectarian. There is no such thing as an “anthroposophical school”. There are only schools – Waldorf Schools – in which the pedagogy is based on an anthroposophical understanding of the nature of man.

“Anthroposophy is a path of cognition from the spiritual in man to the Spiritual in the Universe.”