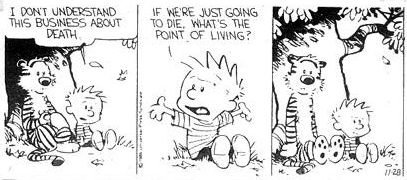

“Everyone now living will be dead in 100 years.”

“Not necessarily so,” my interlocutor objects. “Modern technology could change that…radically.”

“Do you mean it could eliminate death?”

“Anything’s possible.”

A third participant: “Anyway, who cares? If we’re dead we’re dead, no problem.”

That was a real recent conversation about a subject which has baffled humanity since we began thinking about it eons ago. Life, after all, is a great mystery. From the moment it begins it marches inevitably towards death. What, then, is the point?

I like Kierkegaard’s idea (paraphrased from memory): you come to a fork in the road of life. One direction points to despair and suicide, because life involves much suffering and, if it is meaningless, the thinking person will want to end it as soon as possible. The other direction points to faith. K reasons that the philosopher (thinking person) must choose this path if only because the other path leads to such a miserable end. K chose the path of faith – albeit outside the Church – and it worked for him.

But the “thinking person” has changed his thinking today.

Kierkegaard never used the word “existentialism”, and would probably be surprised to learn that he was its founder. For his existentialism was very different from that of the modern existentialists – Sartre, Camus et al. – who rejected the existential label, who were atheists and decided that since we don’t know and will never know what the hell is going on, why not just live , i.e., “exist” the best we can and be as good as we can be. They more or less proved K wrong in that they were able to live constructive lives (mostly), even after having chosen K’s path to despair. Still, they were cultured people and possessed the beauty and lyricism of culture. They could look at the great religious art of the past and listen to the music of the spheres, thereby nurturing their souls. Cheating, as it were.

So where do I (and you) come in? I was born into a Roman Catholic family, the members of which didn’t think much about such existential questions. My parents were young and their priorities were rising above the working class and having a good time. (I don’t mean this critically, they pampered me very nicely.) My father, though, must have had a thing about the Church. I say that because he never went to mass and sent me to public schools instead of Catholic ones. But I had to go to religious instruction once a week at a Catholic school, a program designed for such as I, endangered by a secular education. On one hand my father did me a big favor by not subjecting me to daily brain washing; on the other hand public schools were very inferior to the Catholic schools at that time in Brooklyn. The proof of this is that when I applied to a Catholic high school, my own decision because most of my friends were going there, I didn’t make a high enough score on the entrance exam to be accepted – and I knew I was smarter than many of those who were accepted. (It just occurred to me that the real reason may have been that I came from a public school and not, as the others, from a Catholic one.) Whatever: again I was spared.

But not completely. A well-meaning aunt dragged me to mass every Sunday when I was small and she and the nuns in religious instruction had already imbued my poor little soul with guilt and fear, which are the cornerstones of Catholic teaching – as well as that of other Christian churches.

The first doubt I remember involved the Boy Scouts. There is (or was) a holiday called Brooklyn Day in which the Boy Scout troops marched down the main drags – in our case Ocean Avenue – waving the flags of Brooklyn and, naturally, the United States. This holiday must have had something to do with Protestantism, because one of the kids whose parents were fanatical Catholics said we Catholic Scouts should ask Monsignor King (God’s representative) if we were allowed to participate, just in case it might offend God if we did. So he and another kid, his Sancho Panza, asked Father King, who said no, we were not allowed to participate in that march. I told my father, who told me to march if I wanted to and to forget Father King. I marched, along with most of the rest of the Troop, despite the squealer warning us that we’d go to hell if we did.

Then, a few years later, at mass one Sunday, the priest in his sermon advised us that the new issue of the “index” of forbidden books would be handed out at the door on leaving, that we should strictly obey it – in order not to offend God and Jesus, who were one and the same. When I got home I checked the Index, a long list or books, most of which I’d never heard of, until I came to The Three Musketeers, which I’d just finished reading. What? Why? Then it dawned on me: Cardinal Richelieu was the bad guy. How dared Alexander Dumas accuse a Cardinal of the Church, even fictionally, of being a power-hungry lowlife? Even if he really was. I didn’t care much about that, though. What bothered me was that the Church was banning books just because of criticism.

Then there was Confession. As an adolescent I was a pretty adept masturbater – if I remember correctly, and I do. Did I have the balls to tell that representative of God, the smelly priest in his cubicle about that? Actually no, I was too much ashamed and too much a coward. I never went to Confession again, and only felt even more guilty because of it. I would like to say that I questioned the whole system, feeling that the priest had no more power to forgive sins than I did. Or even if masturbating was a sin at all. (I was convinced it was.) But that didn’t come until later.

Actually, I didn’t really free myself from the Church’s clutches until I was about thirty years old and read a book by Rudolf Steiner – the Philosophy of Freedom. Not that he criticizes the Church there much, but because it’s really about Freedom with a capital F, and the Churches don’t want us to have freedom – they want to tell us what we must think and do.

Another book which was probably also on the Index is The Brothers Karamazov, in which the chapter about The Grand Inquisitor took my breath away. It tells, fictionally, what would happen if Christ came back. He would be rejected by the Church because he might say something contrary to its teachings – about freedom – and man isn’t ready for that.

I was first initiated into the idea of reincarnation by W. Somerset Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge. But there it is postulated from an oriental viewpoint, which is fine for some, but not really my cup of tea.

Reincarnation is intimately associated with the concept of karma, so to illustrate how my karma got me where I am, I’ll tell the story briefly and, I hope, not too boringly.

In 1962 I was working for an international airline association (IATA) and was transferred from New York to Buenos Aires – the only one from the company to be here, meaning no infrastructure or back-up, not even an office, and the telephones seldom worked. Why me? Hard to answer, except that I was in the right place at the right time when we needed someone in Argentina. (karma 2) I didn’t speak Spanish and at first wasn’t sure whether Buenos Aires was in Argentina or Brazil. But off I went with my wife and three-year-old daughter.

Backtrack: I met my German first wife when I was in the U.S. Army in Germany only seven years after the end of the war. Her aunt and uncle were anthroposophists, something I’d never heard of. But, as they were the only interesting people in my wife’s family, I conversed with them fairly frequently. Except for the reincarnation part, I found anthroposophy to be pretty weird. When we were transferred back to the States, they presented me with a copy of Rudolf Steiner’s “An Outline of Occult Science”. I tried to read it, but couldn’t make head nor tail of it, so I stuffed it into my duffel bag and forgot about it. (karma 1)

Fast forward to Buenos Aires: When the uncle heard that we were in Buenos Aires, he wrote (thinking of our daughter) that there was a Rudolf Steiner Schule there. He even gave the address: Warnes 1330 Florida. We had only been in B.A. a couple of weeks and were finding it hard to find a permanent residence on my then miserable salary. One day I was wandering around the city (no office to go to) and found myself on one of B.A.’s main drags: Florida Street, so decided to check out the school. But when I got to 1000 Florida, I was facing the Rio de la Plata. Deciding not to swim to 1300, I turned back to other business.

After living for a month in a temporary apartment in downtown Buenos Aires, we put an ad in one of the city’s German newspapers. There were 2: the Freie Presse (reactionary fascist), and the Argentinische Tageblatt (liberal Jewish). We chose the latter. The next day a guy named Pablo Rosenbaum called offering a chalet in the suburb of Florida. Afterward he told me that his name was really Felix, but the Argentine immigration official apparently didn’t like it, so entered Pablo on his entrance document. When his grandfather immigrated to Germany, the immigration guy had changed his real Polish family name to Rosenbaum. So that was twice his family had been renamed by anti-Semitic bureaucrats. Anyway, the house was just what we needed – and it was in a mostly German speaking enclave, where the ex (sic) -Nazis and the Jews seemed to be getting along.

Our next door neighbors, German Mennonites who had come to Argentina from Russia via Germany and Paraguay, told us that there was a German school a few blocks away. We checked it out and it was the Rudolf Steiner Schule, which I had been looking for on Florida Street in the city, and here it was in the town of Florida. You see, I was used to the American house numbering, so the information I had: “Warnes 1330 Florida” – where “Warnes” meant nothing to me, but it was the name of the street with the number after it in the town of Florida. (karma 3)

It was ideal because our daughter already spoke German, although I was more interested in her retaining her English. So I thought: this is okay for kindergarten, but primary school will be a bilingual English-Spanish one – if we’re in Argentina that long. But after three years of Waldorf kindergarten only an overly ambitious fool of a father would want to take his child away from something so wonderful!

When my daughter was in the second grade a conflict exploded between two groups of teachers. The school Board sided with group A, and our teacher was in the minority group B. They fired her, right in the middle of the school year. The parents objected strongly, we even tried to take over the school in a General Meeting. That failed, so a dozen families took our kids out and founded a new school with “our” teacher. As a ring leader, I became president of the Board as well as moonlighting English teacher – one hour a day before heading off to my day job. (karma 4)

In that position I was more of less obliged to find out what the hell I was representing, so I dug out my copy of Occult Science, which was a bad English translation, so I obtained the German original and waded through that. It’s not an easy book, but at least I had a general idea of what anthroposophy is: still weird, but, Waldorf education, which is based on it, works, so there must have been something I was missing. Then two more, very different Steiner books fell into my hands: The Philosophy of Freedom (already mentioned) and Basic Issues of the Social Question – which, years later, I wound up translating. Not at all weird. It was hard to believe that they were written by the same person. Conclusion: he wasn’t mad.

Later I was transferred to Switzerland, then Germany, where I encountered some of the negative aspects of what happened after Steiner’s death, then back to Argentina, where that school we founded had grown exponentially. But trained teachers were in short supply, so I co-founded the Waldorf Teachers Seminario.

* * *

But enough ego-bio. The main point is that anthroposophy, Rudolf Steiner’s teaching, had answered most of my questions, including the purpose of life and death. It seemed that I already knew the essential answers, only that they had been submerged in my unconscious and needed a jolt to emerge – if only partially, like the proverbial tip of the iceberg.

Am I an existentialist? In a way, yes. Kierkegaard wrote:

When the God-forsaken worldliness of earthly life shuts itself in complacency, the confined air develops poison, the moment gets stuck and stands still, the prospect is lost, a need is felt for a refreshing, enlivening breeze to cleanse the air and dispel the poisonous vapors lest we suffocate in worldliness. … Lovingly to hope all things is the opposite of despairingly to hope nothing at all. Love hopes all things – yet is never put to shame. To relate oneself expectantly to the possibility of the good is to hope. To relate oneself expectantly to the possibility of evil is to fear. By the decision to choose hope one decides infinitely more than it seems, because it is an eternal decision… Works of Love

* * *

Upon this writing (2013) I am 81 years old; therefore near death, statistically at least, something I am eminently aware of because I have no credit, nor could I get a new credit card if I wanted one. But you are also near death, regardless of your age, as you have been since birth. Old age is not the only cause; accidents, natural disasters, illness or war could write FIN to your autobiography at any moment. But if a spiritual world exists as well as the physical one, something you cannot prove to others, but which you can feel within you, then go for it, give it the air necessary to let it rise to your waking consciousness. Death is not proud, sooner or later it takes us all, equally. Better, then, to existentially choose to meet the spiritual world on your own terms, that is, now.