157 pages

Author�s

note:

This is a novel. It is the story of a young man

and his dreams of coming to grips with his meaningless life. His name is

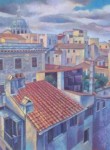

Sebastian. The events take place in the labyrinthine Historic Center of Rome at

the end of the II Millennium.� It begins

with an event that shocks Sebastian out of his deep-seated hopelessness and

urges him to search for his place in life through some heroic action. For if he

vaunts his outsider status, he dreams of somehow of finding a way out of his

labyrinth.

It is the story of one representative of the

uprooted generations that began appearing throughout the world in great numbers

after World War II. People with no sense of homeland. No sense of belonging. No

sense of time. Past, present and future are elusive concepts for them. Unlike

expatriates whose constant dream is to return home, the uprooted, the

deracinated, the rootless, have no true concept of a native land. They

integrate quickly in diverse countries and societies and they speak a language

of placelessness, but ultimately they feel like outsiders everywhere. Neither

foreigners nor natives, they are eternal hybrids.�

The story takes place against a background of

the political terrorism that has plagued Italy and other countries in the

aftermath of the explosions of 1968. Two terrorisms emerged in Italy, Germany

and France: the left-wing terrorism of disillusioned young people who demand a

real revolution to obtain �everything here and now�; the right-wing terrorism

of the sons of European Fascism-Nazism who dream of the past. In most cases the

terrorist organizations were eventually infiltrated and manipulated by secret

services or became criminal associations. The events here are imaginary

although former terrorists, romantic nostalgics like Sergio, and their heirs

regularly raise their heads and dream of old glories.

It is also the story of the relationship

between Sebastian and Luca, the former theoretician of left-wing terrorism who

is above all part of Italian society and of his era. Each of them searches for

sustenance in the other: Sebastian in his desire to emerge into the real world;

Luca in his attempt to understand the internationalism he has always preached.

I began this novel in 1995 to tell the story of

the rootless ones. Dissatisfied with the first draft, I rewrote the entire

story the following year. That too I put aside when I left Italy for Mexico.

Finally, toward the end of the year 2000, I rewrote the novel again, this time

giving more importance to the Sebastian-Luca relationship and to the background

of political unrest and the role of the secret services.

I believe it is an interesting story, a story

worth telling. There are many Sebastian�s around. And more former and active

terrorists than one could even imagine.

On a September afternoon heavy under humid

winds blowing northwards from the Sahara, Sebastian Stone was buying his ticket

at the English-language cinema in an old quarter across the river when he heard

gunshots. He rounded the corner on the run and stopped short alongside a

crumpled body lying on the cobblestones. His first thought was that he had

stumbled onto a film set. But then he saw the puddles of dark blood spreading

over the stones.

He stared at the man standing some ten

meters away, his legs spread, his chin squared, his head lowered. The big man

was holding a pistol in two hands and pointing it at him.

I yelled halt but he didn't stop,� the

vigilante shouted to the people gathered at the scene near the church of Santa

Maria In Trastevere. �He robbed that girl over there.� He was yelling for

everyone to hear, waving his pistol toward a blond girl in a skimpy dress

standing near the church. �I saw him do it.�

Two seconds. The time to blink, and the

boy was dead. Another purse-snatcher was stretched out on the stones next to

his overturned motorbike.

"What the fuck do you want!" the

policeman shouted, pointing his pistol at Sebastian and collecting his courage.

Sebastian�s eyes were riveted on the boy's

body. It was beginning to shrink. A wave of nausea rushed over him. He felt the

blood drain from his face and his stomach turn inside out.

He stared down at the gray face of the

dark-haired boy lying on his back. His mouth was open as if to cry. The red

puddle surrounding him was spreading over the stones toward Sebastian�s dirty

boots. He looked so terribly alone.

�Did you see something?� snarled the

policeman. His broad face had reddened and his eyes bulged as he moved forward,

now with a hint of swagger. Sebastian�s sloppy dress and dirty blond hair too

long for the policeman's tastes seemed to manifest that he was

accomplice-ally-friend of the dead scum on the stones. Scowling under his dark

eyebrows and his hairy chest exposed under a tan shirt opened half way down,

the cop looked like a cornered wild boar.

Sebastian stared at his assailant's hands.

He was now holding the pistol in his right hand while with the fingers of his

left hand spread wide he had cupped his crotch in a half lascivious, half

child-like gesture.

�What're you gaping at, ragazzo?

Move on. Get out of here, or I'll take you in. You're obstructing justice.�

Obstructing justice? He was just going to

the movie. He didn't even want to be a spectator. The maddened cop now

dominated the piazza. Sebastian backtracked to the corner, his heart pounding,

his face red from agitation. It was those assassins hands that were so

terrible. And the reddened Sanpietrini cobblestones.

Betranced bystanders stood motionless.

Silence reigned. He took one last look toward the scene, turned, and went back

to the Cinema Pasquino. That unmistakable metallic tat-tat-tat was still

resounding in his brain. The boy's gray face was before him. Red blood. Dark

death red on the gray-black stones. Blood on stones. Blood and stones.

On the piazza, darkness. In the cinema,

blackness like the death outside. Black like the cobbles. Black, he thought,

like the spectral silhouettes of heads stationary against the rising and

dimming lights from the screen. Pale strange faces along the back row were

motionless. Laughter and back slapping on the screen. The senseless film before

him, its frames edited, cut, ordered, registered � while they were carrying

away the frail body in a black sack. The kid was no more. On his motorbike one

minute, the next sinking into Rome�s black stones. Into a stone grave. No more

worries about his daily dose. No more hunting for victims, no more fear and

terror and pounding heart. His life had been nothing. His death had no

significance. Murdered for snatching a worthless necklace from the neck of a

blond tourist.

Time had stopped. He knew he had stood at

the center of time. That instant of the flash of the gun was an eternity. Yet

it was nothing.

The next afternoon he retraced his steps.

Again he stood where he had stood under the cop's threats. He circled the spot

the body had lain. Nothing of the boy remained, not even traces of blood on the

dirty cobbles. He had vanished. Yet for a moment the

outline of the crumpled body on the stones flashed through his mind as in

isolated, slow motion film frames. The way one thin arm lay crossed over his

chest, his polo shirt blood-soaked, his hair long and curly. For that moment

the memory, the image of the memory - or the memory of the image - was his.

Two days later he was back in Trastevere,

sitting on the shaded terrace at the caf� on the opposite side of the piazza,

facing the portico of the church he had always loved. He was reading clippings

from the Messaggero and La Repubblica about the shooting of a

16-year old purse-snatcher, a Trastevere boy named Pierluigi.

Looking toward the death site, squinting

his eyes and trying to conjure up again the outline of the body, he started: the

elusive image of the boy on the stones was fading. Nearly gone. Again he had

been deceived by slippery memory.

The big policeman was well known on the

square, he read. The cop was known as a bully here in Trastevere where he had

grown up. Like Pierluigi. Probably they had known each other, the executioner

and his victim. One reporter wrote that the policeman�s elementary school

teachers had predicted that that boy would become a criminal. To impress people

in the caf� where Sebastian was now sitting he always carried his pistol in his

belt, pulling it out and waving it around like a flag. Had Pierluigi seen it

too, the pistol that killed him?�

The wary waiter on the caf� terrace

shrugged his shoulders and refused to comment on the cop's character. �Non

lo conosco,� he lied. I don't know him.

�See nothing, hear nothing, know nothing,�

Sebastian murmured. Rigid, motionless, his lips pursed, he contemplated the

Madonna mosaic on the facade of Rome's oldest Christian church on the opposite

side of the piazza - and he felt deluded by her promise.

All those times he had sat around the

fountain in the middle of this piazza, joking with the others, smoking pot and

drinking beer, the Madonna and the enigmatic women carrying lamps in their

outstretched hands frescoed on the wall over the portico and the row of statues

of cardinals along the edge of the overhead balcony had promised him their

sacred protection: shelter for him and the neo-hippies and the drug addicts who

congregated at the fountain, for the vagabonds who lived on the piazza, for the

black Africans who bought and sold anything, for the gays of the quarter, even

those with AIDS, who mingled promiscuously with the others, for the furious

motorcyclists, and for the other outsiders who met here under the shadow of the

ancient Romanesque bell tower. Superstitions, lingering Catholic culture, black

magic? They had believed, Pierluigi and all those disparate members of the

motley group, that for the outcast Piazza Santa Maria di Trastevere was the

safest spot in all of Rome. A haven, a refuge.

We all deserve one, a vagabond philosopher

from Turin preached to the others. A place to pull ourselves together, to find

ourselves again.

Even though Rome is not a poetic city,

this piazza had its poetry - like many of the city's singular squares. Too

ribald, too crass, Rome is too cynical to be poetic, too aggressive and too menefreghista,

devil-may-care. Too greedy for poetry.

Unlike grandiose Paris with its unbounded

perspectives and panoramas, Sebastian�s Rome was tight and closed, mysterious

and arcane. Its short streets, narrow and dark, suddenly, miraculously,

unfolding onto magnificent intimate piazzas, each secluded and

contained. In Rome, from one instant to the next, you step from a cobbled

alley, twisting and curving, black and sunless, onto a dazzling piazza bathed

in sunshine - each time you wonder where it materialized from. The piazza!

Where he'd learned to ride bikes and motor scooters. Where the kids of the

quarter brawl and love.

Each piazza like an inviting salon.

Protective like a homey oasis. A zona franca, a free zone, for the

little man in opposition to caesars and popes and foreign oppressors. Where

secrets abound, while everything is hidden from the eye until it leaps out to

astonish you.

Even if feminine, Rome is not delicate.

More than indifferent and oblivious, she's hard, brutal, cruel. Hard like the

stones from her subsoil, hard like her travertine stone and the volcanic tufa

of her great palazzos and the secular cobbles of her streets, maybe she is a

street-wise transvestite.

The tragedy here, Sebastian came to

realize as he reconstructed the drama over and over, was not only that of

Pierluigi, but of the stupid cop: he wasn't just cruel but also brutal. He'd

wanted the sensation of killing. Now he would feel the passion of that instant

the rest of his life. The boy was his sacrificial victim; he died in vain.

�While I failed miserably.��

�How could I just go to the movie

afterwards as if nothing extraordinary had happened? So what if I reported it

as a murder at police headquarters? What did I expect anyway? A reward? They

just buried my charge in their files. I played no role at all. Not even as a

witness.�

About the author:

Gaither Stewart left journalism three years ago in order to write fiction full-time. Originally from Asheville, North Carolina, he has lived most of his life in Europe, chiefly in Germany and Italy. For many years he was the Italian correspondent of the Rotterdam daily newspaper, ALGEMEEN DAGBLAD. His has been a varied life: from university studies in political science and Slavistics in the United States and Germany, to intelligence officer in Europe, to field correspondent for European and American radios, to public relations for Italian corporations, to full correspondent for a major European newspaper. His journalistic stories have appeared in the press Of West and East Europe. Now during the last year his fiction has appeared In a number of English language literary publications, including the SouthernCross Review. His first book, "The Russian Flask", is also on the SCR e-book list. Gaither lives with his wife, Milena, in the hills of north Rome.

To order click and type �Labyrinth� in the body. We will send you the e-book free of charge by return e-mail.

Remember, you must have Adobe Acrobat Reader. (Click for free download)